/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/71970990/05_nohomework_Jiayue_Li.0.jpg)

Filed under:

- The Highlight

Nobody knows what the point of homework is

The homework wars are back.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Nobody knows what the point of homework is

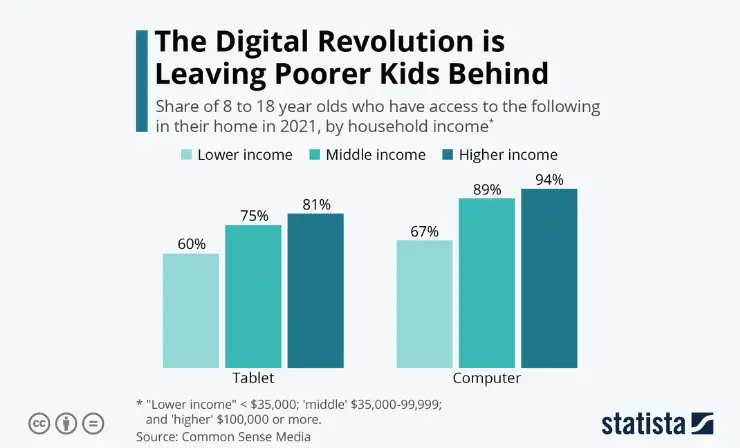

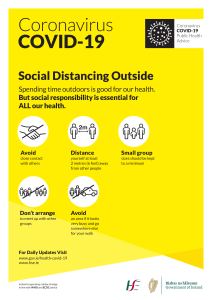

As the Covid-19 pandemic began and students logged into their remote classrooms, all work, in effect, became homework. But whether or not students could complete it at home varied. For some, schoolwork became public-library work or McDonald’s-parking-lot work.

Luis Torres, the principal of PS 55, a predominantly low-income community elementary school in the south Bronx, told me that his school secured Chromebooks for students early in the pandemic only to learn that some lived in shelters that blocked wifi for security reasons. Others, who lived in housing projects with poor internet reception, did their schoolwork in laundromats.

According to a 2021 Pew survey , 25 percent of lower-income parents said their children, at some point, were unable to complete their schoolwork because they couldn’t access a computer at home; that number for upper-income parents was 2 percent.

The issues with remote learning in March 2020 were new. But they highlighted a divide that had been there all along in another form: homework. And even long after schools have resumed in-person classes, the pandemic’s effects on homework have lingered.

Over the past three years, in response to concerns about equity, schools across the country, including in Sacramento, Los Angeles , San Diego , and Clark County, Nevada , made permanent changes to their homework policies that restricted how much homework could be given and how it could be graded after in-person learning resumed.

Three years into the pandemic, as districts and teachers reckon with Covid-era overhauls of teaching and learning, schools are still reconsidering the purpose and place of homework. Whether relaxing homework expectations helps level the playing field between students or harms them by decreasing rigor is a divisive issue without conclusive evidence on either side, echoing other debates in education like the elimination of standardized test scores from some colleges’ admissions processes.

I first began to wonder if the homework abolition movement made sense after speaking with teachers in some Massachusetts public schools, who argued that rather than help disadvantaged kids, stringent homework restrictions communicated an attitude of low expectations. One, an English teacher, said she felt the school had “just given up” on trying to get the students to do work; another argued that restrictions that prohibit teachers from assigning take-home work that doesn’t begin in class made it difficult to get through the foreign-language curriculum. Teachers in other districts have raised formal concerns about homework abolition’s ability to close gaps among students rather than widening them.

Many education experts share this view. Harris Cooper, a professor emeritus of psychology at Duke who has studied homework efficacy, likened homework abolition to “playing to the lowest common denominator.”

But as I learned after talking to a variety of stakeholders — from homework researchers to policymakers to parents of schoolchildren — whether to abolish homework probably isn’t the right question. More important is what kind of work students are sent home with and where they can complete it. Chances are, if schools think more deeply about giving constructive work, time spent on homework will come down regardless.

There’s no consensus on whether homework works

The rise of the no-homework movement during the Covid-19 pandemic tapped into long-running disagreements over homework’s impact on students. The purpose and effectiveness of homework have been disputed for well over a century. In 1901, for instance, California banned homework for students up to age 15, and limited it for older students, over concerns that it endangered children’s mental and physical health. The newest iteration of the anti-homework argument contends that the current practice punishes students who lack support and rewards those with more resources, reinforcing the “myth of meritocracy.”

But there is still no research consensus on homework’s effectiveness; no one can seem to agree on what the right metrics are. Much of the debate relies on anecdotes, intuition, or speculation.

Researchers disagree even on how much research exists on the value of homework. Kathleen Budge, the co-author of Turning High-Poverty Schools Into High-Performing Schools and a professor at Boise State, told me that homework “has been greatly researched.” Denise Pope, a Stanford lecturer and leader of the education nonprofit Challenge Success, said, “It’s not a highly researched area because of some of the methodological problems.”

Experts who are more sympathetic to take-home assignments generally support the “10-minute rule,” a framework that estimates the ideal amount of homework on any given night by multiplying the student’s grade by 10 minutes. (A ninth grader, for example, would have about 90 minutes of work a night.) Homework proponents argue that while it is difficult to design randomized control studies to test homework’s effectiveness, the vast majority of existing studies show a strong positive correlation between homework and high academic achievement for middle and high school students. Prominent critics of homework argue that these correlational studies are unreliable and point to studies that suggest a neutral or negative effect on student performance. Both agree there is little to no evidence for homework’s effectiveness at an elementary school level, though proponents often argue that it builds constructive habits for the future.

For anyone who remembers homework assignments from both good and bad teachers, this fundamental disagreement might not be surprising. Some homework is pointless and frustrating to complete. Every week during my senior year of high school, I had to analyze a poem for English and decorate it with images found on Google; my most distinct memory from that class is receiving a demoralizing 25-point deduction because I failed to present my analysis on a poster board. Other assignments really do help students learn: After making an adapted version of Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book for a ninth grade history project, I was inspired to check out from the library and read a biography of the Chinese ruler.

For homework opponents, the first example is more likely to resonate. “We’re all familiar with the negative effects of homework: stress, exhaustion, family conflict, less time for other activities, diminished interest in learning,” Alfie Kohn, author of The Homework Myth, which challenges common justifications for homework, told me in an email. “And these effects may be most pronounced among low-income students.” Kohn believes that schools should make permanent any moratoria implemented during the pandemic, arguing that there are no positives at all to outweigh homework’s downsides. Recent studies , he argues , show the benefits may not even materialize during high school.

In the Marlborough Public Schools, a suburban district 45 minutes west of Boston, school policy committee chair Katherine Hennessy described getting kids to complete their homework during remote education as “a challenge, to say the least.” Teachers found that students who spent all day on their computers didn’t want to spend more time online when the day was over. So, for a few months, the school relaxed the usual practice and teachers slashed the quantity of nightly homework.

Online learning made the preexisting divides between students more apparent, she said. Many students, even during normal circumstances, lacked resources to keep them on track and focused on completing take-home assignments. Though Marlborough Schools is more affluent than PS 55, Hennessy said many students had parents whose work schedules left them unable to provide homework help in the evenings. The experience tracked with a common divide in the country between children of different socioeconomic backgrounds.

So in October 2021, months after the homework reduction began, the Marlborough committee made a change to the district’s policy. While teachers could still give homework, the assignments had to begin as classwork. And though teachers could acknowledge homework completion in a student’s participation grade, they couldn’t count homework as its own grading category. “Rigorous learning in the classroom does not mean that that classwork must be assigned every night,” the policy stated . “Extensions of class work is not to be used to teach new content or as a form of punishment.”

Canceling homework might not do anything for the achievement gap

The critiques of homework are valid as far as they go, but at a certain point, arguments against homework can defy the commonsense idea that to retain what they’re learning, students need to practice it.

“Doesn’t a kid become a better reader if he reads more? Doesn’t a kid learn his math facts better if he practices them?” said Cathy Vatterott, an education researcher and professor emeritus at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. After decades of research, she said it’s still hard to isolate the value of homework, but that doesn’t mean it should be abandoned.

Blanket vilification of homework can also conflate the unique challenges facing disadvantaged students as compared to affluent ones, which could have different solutions. “The kids in the low-income schools are being hurt because they’re being graded, unfairly, on time they just don’t have to do this stuff,” Pope told me. “And they’re still being held accountable for turning in assignments, whether they’re meaningful or not.” On the other side, “Palo Alto kids” — students in Silicon Valley’s stereotypically pressure-cooker public schools — “are just bombarded and overloaded and trying to stay above water.”

Merely getting rid of homework doesn’t solve either problem. The United States already has the second-highest disparity among OECD (the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) nations between time spent on homework by students of high and low socioeconomic status — a difference of more than three hours, said Janine Bempechat, clinical professor at Boston University and author of No More Mindless Homework .

When she interviewed teachers in Boston-area schools that had cut homework before the pandemic, Bempechat told me, “What they saw immediately was parents who could afford it immediately enrolled their children in the Russian School of Mathematics,” a math-enrichment program whose tuition ranges from $140 to about $400 a month. Getting rid of homework “does nothing for equity; it increases the opportunity gap between wealthier and less wealthy families,” she said. “That solution troubles me because it’s no solution at all.”

A group of teachers at Wakefield High School in Arlington, Virginia, made the same point after the school district proposed an overhaul of its homework policies, including removing penalties for missing homework deadlines, allowing unlimited retakes, and prohibiting grading of homework.

“Given the emphasis on equity in today’s education systems,” they wrote in a letter to the school board, “we believe that some of the proposed changes will actually have a detrimental impact towards achieving this goal. Families that have means could still provide challenging and engaging academic experiences for their children and will continue to do so, especially if their children are not experiencing expected rigor in the classroom.” At a school where more than a third of students are low-income, the teachers argued, the policies would prompt students “to expect the least of themselves in terms of effort, results, and responsibility.”

Not all homework is created equal

Despite their opposing sides in the homework wars, most of the researchers I spoke to made a lot of the same points. Both Bempechat and Pope were quick to bring up how parents and schools confuse rigor with workload, treating the volume of assignments as a proxy for quality of learning. Bempechat, who is known for defending homework, has written extensively about how plenty of it lacks clear purpose, requires the purchasing of unnecessary supplies, and takes longer than it needs to. Likewise, when Pope instructs graduate-level classes on curriculum, she asks her students to think about the larger purpose they’re trying to achieve with homework: If they can get the job done in the classroom, there’s no point in sending home more work.

At its best, pandemic-era teaching facilitated that last approach. Honolulu-based teacher Christina Torres Cawdery told me that, early in the pandemic, she often had a cohort of kids in her classroom for four hours straight, as her school tried to avoid too much commingling. She couldn’t lecture for four hours, so she gave the students plenty of time to complete independent and project-based work. At the end of most school days, she didn’t feel the need to send them home with more to do.

A similar limited-homework philosophy worked at a public middle school in Chelsea, Massachusetts. A couple of teachers there turned as much class as possible into an opportunity for small-group practice, allowing kids to work on problems that traditionally would be assigned for homework, Jessica Flick, a math coach who leads department meetings at the school, told me. It was inspired by a philosophy pioneered by Simon Fraser University professor Peter Liljedahl, whose influential book Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics reframes homework as “check-your-understanding questions” rather than as compulsory work. Last year, Flick found that the two eighth grade classes whose teachers adopted this strategy performed the best on state tests, and this year, she has encouraged other teachers to implement it.

Teachers know that plenty of homework is tedious and unproductive. Jeannemarie Dawson De Quiroz, who has taught for more than 20 years in low-income Boston and Los Angeles pilot and charter schools, says that in her first years on the job she frequently assigned “drill and kill” tasks and questions that she now feels unfairly stumped students. She said designing good homework wasn’t part of her teaching programs, nor was it meaningfully discussed in professional development. With more experience, she turned as much class time as she could into practice time and limited what she sent home.

“The thing about homework that’s sticky is that not all homework is created equal,” says Jill Harrison Berg, a former teacher and the author of Uprooting Instructional Inequity . “Some homework is a genuine waste of time and requires lots of resources for no good reason. And other homework is really useful.”

Cutting homework has to be part of a larger strategy

The takeaways are clear: Schools can make cuts to homework, but those cuts should be part of a strategy to improve the quality of education for all students. If the point of homework was to provide more practice, districts should think about how students can make it up during class — or offer time during or after school for students to seek help from teachers. If it was to move the curriculum along, it’s worth considering whether strategies like Liljedahl’s can get more done in less time.

Some of the best thinking around effective assignments comes from those most critical of the current practice. Denise Pope proposes that, before assigning homework, teachers should consider whether students understand the purpose of the work and whether they can do it without help. If teachers think it’s something that can’t be done in class, they should be mindful of how much time it should take and the feedback they should provide. It’s questions like these that De Quiroz considered before reducing the volume of work she sent home.

More than a year after the new homework policy began in Marlborough, Hennessy still hears from parents who incorrectly “think homework isn’t happening” despite repeated assurances that kids still can receive work. She thinks part of the reason is that education has changed over the years. “I think what we’re trying to do is establish that homework may be an element of educating students,” she told me. “But it may not be what parents think of as what they grew up with. ... It’s going to need to adapt, per the teaching and the curriculum, and how it’s being delivered in each classroom.”

For the policy to work, faculty, parents, and students will all have to buy into a shared vision of what school ought to look like. The district is working on it — in November, it hosted and uploaded to YouTube a round-table discussion on homework between district administrators — but considering the sustained confusion, the path ahead seems difficult.

When I asked Luis Torres about whether he thought homework serves a useful part in PS 55’s curriculum, he said yes, of course it was — despite the effort and money it takes to keep the school open after hours to help them do it. “The children need the opportunity to practice,” he said. “If you don’t give them opportunities to practice what they learn, they’re going to forget.” But Torres doesn’t care if the work is done at home. The school stays open until around 6 pm on weekdays, even during breaks. Tutors through New York City’s Department of Youth and Community Development programs help kids with work after school so they don’t need to take it with them.

As schools weigh the purpose of homework in an unequal world, it’s tempting to dispose of a practice that presents real, practical problems to students across the country. But getting rid of homework is unlikely to do much good on its own. Before cutting it, it’s worth thinking about what good assignments are meant to do in the first place. It’s crucial that students from all socioeconomic backgrounds tackle complex quantitative problems and hone their reading and writing skills. It’s less important that the work comes home with them.

Jacob Sweet is a freelance writer in Somerville, Massachusetts. He is a frequent contributor to the New Yorker, among other publications.

Will you help keep Vox free for all?

Millions rely on Vox’s journalism to understand the coronavirus crisis. We believe it pays off for all of us, as a society and a democracy, when our neighbors and fellow citizens can access clear, concise information on the pandemic. But our distinctive explanatory journalism is expensive. Support from our readers helps us keep it free for everyone. If you have already made a financial contribution to Vox, thank you. If not, please consider making a contribution today from as little as $3.

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Can we protect and profit from the oceans?

Sometimes kids need a push. here’s how to do it kindly., who gets to flourish, sign up for the newsletter today, explained, thanks for signing up.

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

Helpline PH

The impact of no homework policy: a comprehensive analysis.

Table of Contents

Introduction

The No Homework Policy, a revolutionary concept in the education sector, has been a subject of intense debate among educators, parents, and students alike. This policy, which aims to eliminate or significantly reduce homework, has been met with both applause and criticism. This article delves into the impact of the No Homework Policy, drawing from personal experiences of teachers and students who have been significantly affected by it.

The Traditional Role of Homework

Historically, homework has been viewed as an essential tool for reinforcing what students learn during the school day, preparing for upcoming lessons, and providing parents with a window into their children’s academic progress. However, critics argue that homework often leads to stress and burnout, infringes on students’ personal time, and exacerbates social inequalities.

The Student Perspective

From a student’s perspective, the No Homework Policy has had a profound impact. Many students have reported feeling less stressed and more able to balance their academic responsibilities with extracurricular activities and family time. However, some students feel that the policy has made it more difficult for them to retain information and fully understand the material taught in class.

The Teacher Perspective

Teachers, too, have had mixed reactions to the No Homework Policy. Some teachers feel that the policy allows them to focus more on in-class instruction and less on grading homework. However, others worry that without homework, students may not be getting enough practice with new concepts.

The Impact on Learning

Research has shown that homework can play a significant role in reinforcing the concepts taught in class. However, excessive homework can lead to burnout and stress, negatively impacting a student’s ability to learn and retain information. The No Homework Policy aims to strike a balance, reducing the burden of homework while ensuring that students still have opportunities to practice and reinforce what they’ve learned.

The Impact on Family Time

One of the significant benefits of the No Homework Policy is the potential for increased family time. With less homework to complete, students have more time to spend with their families, engage in hobbies, and simply relax and recharge. This can lead to improved mental health and overall well-being for students.

Effects on Educators

Educators have also experienced a variety of reactions to the No Homework Policy. For some, the policy has allowed them to shift their focus towards more in-depth in-class instruction, reducing the time spent on grading homework. However, there are concerns among others that the absence of homework may limit students’ opportunities to practice new concepts.

Influence on the Educational Landscape

The No Homework Policy has also left its mark on the broader educational landscape. It has challenged conventional norms and prompted educators to reconsider their teaching methodologies. While some educational institutions have welcomed the policy, others have shown resistance, resulting in a diverse array of practices across different schools and districts.

The Impact on Parent-Teacher Relationships

The No Homework Policy has also affected the relationships between parents and teachers. With less homework to monitor, parents may feel less involved in their child’s education. On the other hand, some parents have welcomed the policy, appreciating the reduced stress and increased family time it provides.

Implications for Student Success

The debate around the No Homework Policy’s influence on student success is ongoing. Some studies indicate that homework can boost academic outcomes, particularly for older students. Conversely, other research highlights that an overabundance of homework can lead to student burnout and disengagement, potentially negatively affecting academic success in the long term.

Final Thoughts

In wrapping up, the No Homework Policy is a complex issue with a broad range of implications. It’s evident that this policy has instigated significant changes in the experiences of both educators and learners. As we continue to navigate this conversation, it’s crucial to consider these personal experiences and aim for a balanced approach that encourages learning while also prioritizing the wellbeing of students and teachers.

Looking Forward

As we cast our gaze towards the future of education, it’s important to continually assess the effects of the No Homework Policy. As an increasing number of schools adopt this policy, we’ll gain a more comprehensive understanding of its impact on students, teachers, and the educational landscape as a whole. It’s also key to explore other strategies that can offer the benefits of homework, such as practice and reinforcement of learning, without leading to undue stress and burnout.

OUR LATEST POST

Gender-based haircut policies in schools are absurd, outdated, and irrelevant – Solon

Vice President Sara Duterte Advises Against Punishing Teacher Over TikTok Incident

Periodical Test with TOS for Grade 1 to 6: Complete Compilation

Early Language Literacy and Numeracy Assessment (ELLNA) Reviewer

Mandatory Contributions from Teachers Should Stop

The Education System in Taiwan: A Game Changer

Stay in touch.

Unlock Your Potential: Subscribe Now for More FREE Training with CPD Units!

© 2024 HelplinePH. All Rights Reserved.

Shop TODAY All Stars: Vote for your favorite spring finds

- TODAY Plaza

- Share this —

- Watch Full Episodes

- Read With Jenna

- Inspirational

- Relationships

- TODAY Table

- Newsletters

- Start TODAY

- Shop TODAY Awards

- Citi Music Series

- Listen All Day

Follow today

More Brands

- On The Show

The end of homework? Why some schools are banning homework

Fed up with the tension over homework, some schools are opting out altogether.

No-homework policies are popping up all over, including schools in the U.S., where the shift to the Common Core curriculum is prompting educators to rethink how students spend their time.

“Homework really is a black hole,” said Etta Kralovec, an associate professor of teacher education at the University of Arizona South and co-author of “The End of Homework: How Homework Disrupts Families, Overburdens Children, and Limits Learning.”

“I think teachers are going to be increasingly interested in having total control over student learning during the class day and not relying on homework as any kind of activity that’s going to support student learning.”

College de Saint-Ambroise, an elementary school in Quebec, is the latest school to ban homework, announcing this week that it would try the new policy for a year. The decision came after officials found that it was “becoming more and more difficult” for children to devote time to all the assignments they were bringing home, Marie-Ève Desrosiers, a spokeswoman with the Jonquière School Board, told the CBC .

Kralovec called the ban on homework a movement, though she estimated just a small handful of schools in the U.S. have such policies.

Gaithersburg Elementary School in Rockville, Maryland, is one of them, eliminating the traditional concept of homework in 2012. The policy is still in place and working fine, Principal Stephanie Brant told TODAY Parents. The school simply asks that students read 30 minutes each night.

“We felt like with the shift to the Common Core curriculum, and our knowledge of how our students need to think differently… we wanted their time to be spent in meaningful ways,” Brant said.

“We’re constantly asking parents for feedback… and everyone’s really happy with it so far. But it’s really a culture shift.”

It was a decision that was best for her community, Brant said, adding that she often gets phone calls from other principals inquiring how it’s working out.

The VanDamme Academy, a private K-8 school in Aliso Viejo, California, has a similar policy , calling homework “largely pointless.”

The Buffalo Academy of Scholars, a private school in Buffalo, New York, touts that it has called “a truce in the homework battle” and promises that families can “enjoy stress-free, homework-free evenings and more quality time together at home.”

Some schools have taken yet another approach. At Ridgewood High School in Norridge, Illinois, teachers do assign homework but it doesn’t count towards a student’s final grade.

Many schools in the U.S. have toyed with the idea of opting out of homework, but end up changing nothing because it is such a contentious issue among parents, Kralovec noted.

“There’s a huge philosophical divide between parents who want their kids to be very scheduled, very driven, and very ambitiously focused at school -- those parents want their kids to do homework,” she said.

“And then there are the parents who want a more child-centered life with their kids, who want their kids to be able to explore different aspects of themselves, who think their kids should have free time.”

So what’s the right amount of time to spend on homework?

National PTA spokeswoman Heidi May pointed to the organization’s “ 10 minute rule ,” which recommends kids spend about 10 minutes on homework per night for every year they’re in school. That would mean 10 minutes for a first-grader and an hour for a child in the sixth grade.

But many parents say their kids must spend much longer on their assignments. Last year, a New York dad tried to do his eight-grader’s homework for a week and it took him at least three hours on most nights.

More than 80 percent of respondents in a TODAY.com poll complained kids have too much homework. For homework critics like Kralovec, who said research shows homework has little value at the elementary and middle school level, the issue is simple.

“Kids are at school 7 or 8 hours a day, that’s a full working day and why should they have to take work home?” she asked.

Follow A. Pawlowski on Google+ and Twitter .

Social Sciences

© 2024 Inquiries Journal/Student Pulse LLC . All rights reserved. ISSN: 2153-5760.

Disclaimer: content on this website is for informational purposes only. It is not intended to provide medical or other professional advice. Moreover, the views expressed here do not necessarily represent the views of Inquiries Journal or Student Pulse, its owners, staff, contributors, or affiliates.

Home | Current Issue | Blog | Archives | About The Journal | Submissions Terms of Use :: Privacy Policy :: Contact

Need an Account?

Forgot password? Reset your password »

Is Homework Good for Kids? Here’s What the Research Says

A s kids return to school, debate is heating up once again over how they should spend their time after they leave the classroom for the day.

The no-homework policy of a second-grade teacher in Texas went viral last week , earning praise from parents across the country who lament the heavy workload often assigned to young students. Brandy Young told parents she would not formally assign any homework this year, asking students instead to eat dinner with their families, play outside and go to bed early.

But the question of how much work children should be doing outside of school remains controversial, and plenty of parents take issue with no-homework policies, worried their kids are losing a potential academic advantage. Here’s what you need to know:

For decades, the homework standard has been a “10-minute rule,” which recommends a daily maximum of 10 minutes of homework per grade level. Second graders, for example, should do about 20 minutes of homework each night. High school seniors should complete about two hours of homework each night. The National PTA and the National Education Association both support that guideline.

But some schools have begun to give their youngest students a break. A Massachusetts elementary school has announced a no-homework pilot program for the coming school year, lengthening the school day by two hours to provide more in-class instruction. “We really want kids to go home at 4 o’clock, tired. We want their brain to be tired,” Kelly Elementary School Principal Jackie Glasheen said in an interview with a local TV station . “We want them to enjoy their families. We want them to go to soccer practice or football practice, and we want them to go to bed. And that’s it.”

A New York City public elementary school implemented a similar policy last year, eliminating traditional homework assignments in favor of family time. The change was quickly met with outrage from some parents, though it earned support from other education leaders.

New solutions and approaches to homework differ by community, and these local debates are complicated by the fact that even education experts disagree about what’s best for kids.

The research

The most comprehensive research on homework to date comes from a 2006 meta-analysis by Duke University psychology professor Harris Cooper, who found evidence of a positive correlation between homework and student achievement, meaning students who did homework performed better in school. The correlation was stronger for older students—in seventh through 12th grade—than for those in younger grades, for whom there was a weak relationship between homework and performance.

Cooper’s analysis focused on how homework impacts academic achievement—test scores, for example. His report noted that homework is also thought to improve study habits, attitudes toward school, self-discipline, inquisitiveness and independent problem solving skills. On the other hand, some studies he examined showed that homework can cause physical and emotional fatigue, fuel negative attitudes about learning and limit leisure time for children. At the end of his analysis, Cooper recommended further study of such potential effects of homework.

Despite the weak correlation between homework and performance for young children, Cooper argues that a small amount of homework is useful for all students. Second-graders should not be doing two hours of homework each night, he said, but they also shouldn’t be doing no homework.

Not all education experts agree entirely with Cooper’s assessment.

Cathy Vatterott, an education professor at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, supports the “10-minute rule” as a maximum, but she thinks there is not sufficient proof that homework is helpful for students in elementary school.

“Correlation is not causation,” she said. “Does homework cause achievement, or do high achievers do more homework?”

Vatterott, the author of Rethinking Homework: Best Practices That Support Diverse Needs , thinks there should be more emphasis on improving the quality of homework tasks, and she supports efforts to eliminate homework for younger kids.

“I have no concerns about students not starting homework until fourth grade or fifth grade,” she said, noting that while the debate over homework will undoubtedly continue, she has noticed a trend toward limiting, if not eliminating, homework in elementary school.

The issue has been debated for decades. A TIME cover in 1999 read: “Too much homework! How it’s hurting our kids, and what parents should do about it.” The accompanying story noted that the launch of Sputnik in 1957 led to a push for better math and science education in the U.S. The ensuing pressure to be competitive on a global scale, plus the increasingly demanding college admissions process, fueled the practice of assigning homework.

“The complaints are cyclical, and we’re in the part of the cycle now where the concern is for too much,” Cooper said. “You can go back to the 1970s, when you’ll find there were concerns that there was too little, when we were concerned about our global competitiveness.”

Cooper acknowledged that some students really are bringing home too much homework, and their parents are right to be concerned.

“A good way to think about homework is the way you think about medications or dietary supplements,” he said. “If you take too little, they’ll have no effect. If you take too much, they can kill you. If you take the right amount, you’ll get better.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Biden’s Campaign Is In Trouble. Will the Turnaround Plan Work?

- Why We're Spending So Much Money Now

- The Financial Influencers Women Actually Want to Listen To

- Breaker Sunny Choi Is Heading to Paris

- The UAE Is on a Mission to Become an AI Power

- Why TV Can’t Stop Making Silly Shows About Lady Journalists

- The Case for Wearing Shoes in the House

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Katie Reilly at [email protected]

You May Also Like

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

12.2: Types of Persuasive Speeches

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 145387

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate among the four types of persuasive claims.

- Understand how the four types of persuasive claims lead to different types of persuasive speeches.

- Explain the two types of policy claims.

Burns Library, Boston College – Maya Angelou – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Obviously, there are many different persuasive speech topics you could select for a public speaking class. Anything from localized claims like changing a specific college or university policy to larger societal claims like adding more enforcement against the trafficking of women and children in the United States could make for an interesting persuasive speech. You’ll notice in the previous sentence we referred to the two topics as claims. In this use of the word “claim,” we are declaring the goodness or desirability of an attitude, value, belief, or behavior that others may dispute. As a result of the dispute between our perceptions of the desirability of an attitude, value, belief, or behavior and the perceptions of others, we attempt to persuade others by supporting our claim with some sort of evidence and logic. There are four common claims that can be made: definitional, factual, policy, and value.

Definitional Claims

The first type of claim that a persuasive speaker can make is a definitional (or classification) claim. Definitional claims are claims over the denotation or classification of what something is. In essence, we are trying to argue for what something is or what something is not. Most definitional claims fall to a basic argument formula:

Y has features A , B , and C . X is (or is not) a Y because it has (or does not have) features A , B , or C .

For example, maybe you’re trying to persuade your classmates that while therapeutic massage is often performed on nude clients, it is not a form of prostitution. You could start by explaining what therapeutic massage is and then look at the legal definition of prostitution and demonstrate to your peers that therapeutic massage does not fall into the legal definition of prostitution because it does not involve the behaviors characterized by that definition.

Factual Claims

Factual claims set out to argue the truth or falsity of an assertion. Some factual claims are simple to answer: Barack Obama is the first African American President of the United States; the tallest man in the world, Robert Wadlow, was eight feet and eleven inches tall; Facebook wasn’t profitable until 2009. All these factual claims are well documented by evidence and can be easily supported with some research.

However, many factual claims cannot be answered absolutely. It is difficult to determine the truth or falsity of some factual claims because the final answer on the subject has not been discovered (e.g., when does life begin). Probably the most historically interesting and consistent factual claim is the existence of a higher power, God, or other religious deities. The simple fact of the matter is that there is not enough evidence to clearly answer this factual claim in any specific direction.

Other factual claims that may not be easily answered using evidence are predictions of what may or may not happen. For example, you could give a speech on the future of climate change or the future of terrorism in the United States. While there may be evidence that something may happen in the future, you can't actually say with 100% certainty that it will happen in the future.

When thinking of factual claims, it often helps to pretend that you’re putting a specific claim on trial, and as the speaker it is your job to defend your claim as a lawyer would defend a client. Ultimately, your job is to be more persuasive than your audience members who act as both opposition attorneys and judges.

Policy Claims

The third type of persuasive claim is the policy claim—a statement about the nature of a problem and the solution that should be implemented. Policy claims are probably the most common form of persuasive speaking because we are surrounded by problems and people who have ideas about how to fix these problems. Let’s look at a few examples of possible policy claims:

- The United States should stop capital punishment.

- The United States should become independent from the use of foreign oil by allowing more offshore drilling off its coasts.

- The United States should make human cloning for organ donation illegal.

- The U.S. Congress should change sentencing laws so nonviolent drug offenders are sent to rehabilitation centers instead of prison.

- The U.S. Congress should require the tobacco industry to pay 100% of the medical bills for individuals dying of smoking-related cancers.

- The United States should divert the funding from United States Agency for International Development (U.S. AID) to prevent poverty in the United States rather than feeding the starving people around the world.

Each of these claims has a clear perspective that is being advocated. Policy claims will always have a clear and direct opinion on what should occur and what needs to change. When examining policy claims, we generally talk about two different persuasive goals: passive agreement and immediate action.

1) Gain Passive Agreement

When we attempt to gain the passive agreement of our audience, our goal is to get them to agree with our specific policy without asking them to do anything to enact the policy. For example, maybe your speech is on why the Federal Communications Commission should regulate violence on television like it does foul language (i.e., no violence until after 9 p.m.). Your goal as a speaker is to get your audience to agree that it is in our best interest as a society to prevent violence from being shown on television before 9 p.m., but you are not seeking to have your audience run out and call their senators or congressmen or even sign a petition. Often the first step in larger political change is simply getting a large portion of the population to agree with your policy perspective.

Let’s look at a few more passive agreement claims:

- Racial profiling of individuals suspected of belonging to known terrorist groups is a way to make the United States safer.

- Requiring U.S. citizens to “show their papers” is a violation of democracy and resembles the tactics of Nazi Germany and communist Russia.

- Colleges and universities should implement a standardized testing program to ensure student learning outcomes are similar across different institutions.

In each of these claims, the goal is to sway one’s audience to a specific attitude, value, or belief, but not necessarily to get the audience to enact any specific behaviors.

2) Gain Immediate Action

The alternative to passive agreement is immediate action or persuading your audience to start engaging in a specific behavior. Many passive agreement topics can become immediate action topics as soon as you tell your audience what behavior they should engage in (e.g., sign a petition, call a senator, vote). While it is much easier to elicit passive agreement than to get people to do something, you should always try to get your audience to act and do so quickly. A common mistake that speakers make is telling people to do something that will occur in the future. The longer it takes for people to engage in the action you desire, the less likely it is that your audience will engage in that behavior.

Here are some examples of good claims with immediate calls to action:

- College students should eat more fruit, so I am encouraging everyone to eat the apple I have provided you and start getting more fruit in your diet.

- Teaching a child to read is one way to ensure that the next generation will be stronger than those that have come before us, so please sign up right now to volunteer one hour a week to help teach a child to read.

- The United States should reduce its nuclear arsenal by 20 percent over the next five years. Please sign the letter provided encouraging the president to take this necessary step for global peace. Once you’ve signed the letter, hand it to me, and I’ll fax it to the White House today.

Each of these three examples starts with a basic claim and then tags on an immediate call to action. Remember, the faster you can get people to engage in a behavior, the more likely they actually will.

Value Claims

The final type of claim is a value claim, which is a claim where the speaker is making a judgment claim about something (e.g., it’s good or bad, it’s right or wrong, it’s beautiful or ugly, moral or immoral).

Let’s look at three value claims. We’ve italicized the evaluative term in each claim:

- Dating people on the Internet is an immoral form of dating.

- The Lincoln statue in Washington D.C. is ugly .

- It’s unfair for pregnant women to have special parking spaces at malls, shopping centers, and stores.

Each of these three claims could definitely be made by a speaker and other speakers could say the exact opposite. When making a value claim, it’s hard to ascertain why someone has chosen a specific value stance without understanding her or his criteria for making the evaluative statement. For example, if someone finds all forms of technology immoral, then it’s really no surprise that he or she would find Internet dating immoral as well. As such, you need to clearly explain your criteria for making the evaluative statement. For example, when we examine the claim about Lincoln's statue, if your criteria for the term “ugly” is its style of carving or its proportion compared to its location then your evaluative statement can be more easily understood and evaluated by your audience. If, however, you state that your criterion is that Lincoln was a bad person because of what he did to the first nation people of America, then your statement takes on a slightly different meaning. Ultimately, when making a value claim, you need to make sure that you clearly label your evaluative term and provide clear criteria for how you came to that evaluation.

Key Takeaways

- There are four types of persuasive claims. Definition claims argue the denotation or classification of what something is. Factual claims argue the truth or falsity of an assertion being made. Policy claims argue the nature of a problem and the solution that should be taken. Lastly, value claims argue a judgment about something (e.g., it’s good or bad, it’s right or wrong, it’s beautiful or ugly, moral or immoral).

- Each of the four claims leads to different types of persuasive speeches. As such, public speakers need to be aware of the type of claim they are advocating for, in order to understand the best methods of persuasion.

- In policy claims, persuaders attempt to convince their audiences to either passively accept or actively act. When persuaders attempt to gain passive agreement from an audience, they hope that an audience will agree with what is said about a specific policy without asking the audience to do anything to enact that policy. Gaining immediate action, on the other hand, occurs when a persuader gets the audience to actively engage in a specific behavior.

- Look at the list of the top one hundred speeches in the United States during the twentieth century compiled by Stephen E. Lucas and Martin J. Medhurst ( http://www.americanrhetoric.com/top100speechesall.html ). Select a speech and examine the speech to determine which type of claim is being made by the speech.

- Look at the list of the top one hundred speeches in the United States during the twentieth century compiled by Stephen E. Lucas and Martin J. Medhurst and find a policy speech ( http://www.americanrhetoric.com/top100speechesall.html ). Which type of policy outcome was the speech aimed at achieving—passive agreement or immediate action? What evidence do you have from the speech to support your answer?

Home » Tips for Teachers » 7 Research-Based Reasons Why Students Should Not Have Homework: Academic Insights, Opposing Perspectives & Alternatives

7 Research-Based Reasons Why Students Should Not Have Homework: Academic Insights, Opposing Perspectives & Alternatives

In recent years, the question of why students should not have homework has become a topic of intense debate among educators, parents, and students themselves. This discussion stems from a growing body of research that challenges the traditional view of homework as an essential component of academic success. The notion that homework is an integral part of learning is being reevaluated in light of new findings about its effectiveness and impact on students’ overall well-being.

The push against homework is not just about the hours spent on completing assignments; it’s about rethinking the role of education in fostering the well-rounded development of young individuals. Critics argue that homework, particularly in excessive amounts, can lead to negative outcomes such as stress, burnout, and a diminished love for learning. Moreover, it often disproportionately affects students from disadvantaged backgrounds, exacerbating educational inequities. The debate also highlights the importance of allowing children to have enough free time for play, exploration, and family interaction, which are crucial for their social and emotional development.

Checking 13yo’s math homework & I have just one question. I can catch mistakes & help her correct. But what do kids do when their parent isn’t an Algebra teacher? Answer: They get frustrated. Quit. Get a bad grade. Think they aren’t good at math. How is homework fair??? — Jay Wamsted (@JayWamsted) March 24, 2022

As we delve into this discussion, we explore various facets of why reducing or even eliminating homework could be beneficial. We consider the research, weigh the pros and cons, and examine alternative approaches to traditional homework that can enhance learning without overburdening students.

Once you’ve finished this article, you’ll know:

- Insights from Teachers and Education Industry Experts →

- 7 Reasons Why Students Should Not Have Homework →

- Opposing Views on Homework Practices →

- Exploring Alternatives to Homework →

Insights from Teachers and Education Industry Experts: Diverse Perspectives on Homework

In the ongoing conversation about the role and impact of homework in education, the perspectives of those directly involved in the teaching process are invaluable. Teachers and education industry experts bring a wealth of experience and insights from the front lines of learning. Their viewpoints, shaped by years of interaction with students and a deep understanding of educational methodologies, offer a critical lens through which we can evaluate the effectiveness and necessity of homework in our current educational paradigm.

Check out this video featuring Courtney White, a high school language arts teacher who gained widespread attention for her explanation of why she chooses not to assign homework.

Here are the insights and opinions from various experts in the educational field on this topic:

“I teach 1st grade. I had parents ask for homework. I explained that I don’t give homework. Home time is family time. Time to play, cook, explore and spend time together. I do send books home, but there is no requirement or checklist for reading them. Read them, enjoy them, and return them when your child is ready for more. I explained that as a parent myself, I know they are busy—and what a waste of energy it is to sit and force their kids to do work at home—when they could use that time to form relationships and build a loving home. Something kids need more than a few math problems a week.” — Colleen S. , 1st grade teacher

“The lasting educational value of homework at that age is not proven. A kid says the times tables [at school] because he studied the times tables last night. But over a long period of time, a kid who is drilled on the times tables at school, rather than as homework, will also memorize their times tables. We are worried about young children and their social emotional learning. And that has to do with physical activity, it has to do with playing with peers, it has to do with family time. All of those are very important and can be removed by too much homework.” — David Bloomfield , education professor at Brooklyn College and the City University of New York graduate center

“Homework in primary school has an effect of around zero. In high school it’s larger. (…) Which is why we need to get it right. Not why we need to get rid of it. It’s one of those lower hanging fruit that we should be looking in our primary schools to say, ‘Is it really making a difference?’” — John Hattie , professor

”Many kids are working as many hours as their overscheduled parents and it is taking a toll – psychologically and in many other ways too. We see kids getting up hours before school starts just to get their homework done from the night before… While homework may give kids one more responsibility, it ignores the fact that kids do not need to grow up and become adults at ages 10 or 12. With schools cutting recess time or eliminating playgrounds, kids absorb every single stress there is, only on an even higher level. Their brains and bodies need time to be curious, have fun, be creative and just be a kid.” — Pat Wayman, teacher and CEO of HowtoLearn.com

7 Reasons Why Students Should Not Have Homework

Let’s delve into the reasons against assigning homework to students. Examining these arguments offers important perspectives on the wider educational and developmental consequences of homework practices.

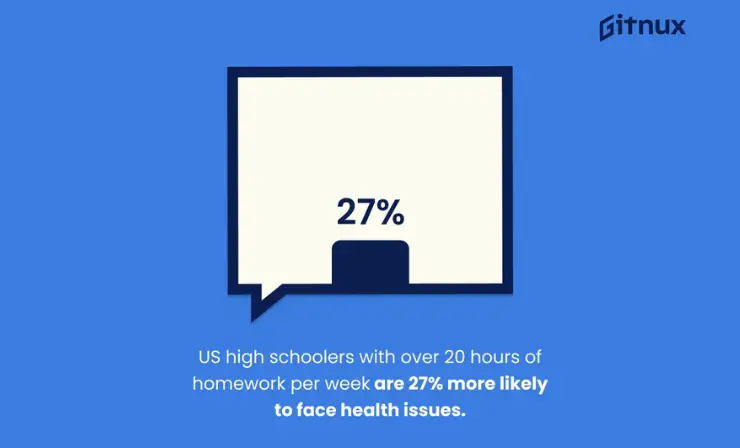

1. Elevated Stress and Health Consequences

The ongoing debate about homework often focuses on its educational value, but a vital aspect that cannot be overlooked is the significant stress and health consequences it brings to students. In the context of American life, where approximately 70% of people report moderate or extreme stress due to various factors like mass shootings, healthcare affordability, discrimination, racism, sexual harassment, climate change, presidential elections, and the need to stay informed, the additional burden of homework further exacerbates this stress, particularly among students.

Key findings and statistics reveal a worrying trend:

- Overwhelming Student Stress: A staggering 72% of students report being often or always stressed over schoolwork, with a concerning 82% experiencing physical symptoms due to this stress.

- Serious Health Issues: Symptoms linked to homework stress include sleep deprivation, headaches, exhaustion, weight loss, and stomach problems.

- Sleep Deprivation: Despite the National Sleep Foundation recommending 8.5 to 9.25 hours of sleep for healthy adolescent development, students average just 6.80 hours of sleep on school nights. About 68% of students stated that schoolwork often or always prevented them from getting enough sleep, which is critical for their physical and mental health.

- Turning to Unhealthy Coping Mechanisms: Alarmingly, the pressure from excessive homework has led some students to turn to alcohol and drugs as a way to cope with stress.

This data paints a concerning picture. Students, already navigating a world filled with various stressors, find themselves further burdened by homework demands. The direct correlation between excessive homework and health issues indicates a need for reevaluation. The goal should be to ensure that homework if assigned, adds value to students’ learning experiences without compromising their health and well-being.

By addressing the issue of homework-related stress and health consequences, we can take a significant step toward creating a more nurturing and effective educational environment. This environment would not only prioritize academic achievement but also the overall well-being and happiness of students, preparing them for a balanced and healthy life both inside and outside the classroom.

2. Inequitable Impact and Socioeconomic Disparities

In the discourse surrounding educational equity, homework emerges as a factor exacerbating socioeconomic disparities, particularly affecting students from lower-income families and those with less supportive home environments. While homework is often justified as a means to raise academic standards and promote equity, its real-world impact tells a different story.

The inequitable burden of homework becomes starkly evident when considering the resources required to complete it, especially in the digital age. Homework today often necessitates a computer and internet access – resources not readily available to all students. This digital divide significantly disadvantages students from lower-income backgrounds, deepening the chasm between them and their more affluent peers.

Key points highlighting the disparities:

- Digital Inequity: Many students lack access to necessary technology for homework, with low-income families disproportionately affected.

- Impact of COVID-19: The pandemic exacerbated these disparities as education shifted online, revealing the extent of the digital divide.

- Educational Outcomes Tied to Income: A critical indicator of college success is linked more to family income levels than to rigorous academic preparation. Research indicates that while 77% of students from high-income families graduate from highly competitive colleges, only 9% from low-income families achieve the same . This disparity suggests that the pressure of heavy homework loads, rather than leveling the playing field, may actually hinder the chances of success for less affluent students.

Moreover, the approach to homework varies significantly across different types of schools. While some rigorous private and preparatory schools in both marginalized and affluent communities assign extreme levels of homework, many progressive schools focusing on holistic learning and self-actualization opt for no homework, yet achieve similar levels of college and career success. This contrast raises questions about the efficacy and necessity of heavy homework loads in achieving educational outcomes.

The issue of homework and its inequitable impact is not just an academic concern; it is a reflection of broader societal inequalities. By continuing practices that disproportionately burden students from less privileged backgrounds, the educational system inadvertently perpetuates the very disparities it seeks to overcome.

3. Negative Impact on Family Dynamics

Homework, a staple of the educational system, is often perceived as a necessary tool for academic reinforcement. However, its impact extends beyond the realm of academics, significantly affecting family dynamics. The negative repercussions of homework on the home environment have become increasingly evident, revealing a troubling pattern that can lead to conflict, mental health issues, and domestic friction.

A study conducted in 2015 involving 1,100 parents sheds light on the strain homework places on family relationships. The findings are telling:

- Increased Likelihood of Conflicts: Families where parents did not have a college degree were 200% more likely to experience fights over homework.

- Misinterpretations and Misunderstandings: Parents often misinterpret their children’s difficulties with homework as a lack of attention in school, leading to feelings of frustration and mistrust on both sides.

- Discriminatory Impact: The research concluded that the current approach to homework disproportionately affects children whose parents have lower educational backgrounds, speak English as a second language, or belong to lower-income groups.

The issue is not confined to specific demographics but is a widespread concern. Samantha Hulsman, a teacher featured in Education Week Teacher , shared her personal experience with the toll that homework can take on family time. She observed that a seemingly simple 30-minute assignment could escalate into a three-hour ordeal, causing stress and strife between parents and children. Hulsman’s insights challenge the traditional mindset about homework, highlighting a shift towards the need for skills such as collaboration and problem-solving over rote memorization of facts.

The need of the hour is to reassess the role and amount of homework assigned to students. It’s imperative to find a balance that facilitates learning and growth without compromising the well-being of the family unit. Such a reassessment would not only aid in reducing domestic conflicts but also contribute to a more supportive and nurturing environment for children’s overall development.

4. Consumption of Free Time

In recent years, a growing chorus of voices has raised concerns about the excessive burden of homework on students, emphasizing how it consumes their free time and impedes their overall well-being. The issue is not just the quantity of homework, but its encroachment on time that could be used for personal growth, relaxation, and family bonding.

Authors Sara Bennett and Nancy Kalish , in their book “The Case Against Homework,” offer an insightful window into the lives of families grappling with the demands of excessive homework. They share stories from numerous interviews conducted in the mid-2000s, highlighting the universal struggle faced by families across different demographics. A poignant account from a parent in Menlo Park, California, describes nightly sessions extending until 11 p.m., filled with stress and frustration, leading to a soured attitude towards school in both the child and the parent. This narrative is not isolated, as about one-third of the families interviewed expressed feeling crushed by the overwhelming workload.

Key points of concern:

- Excessive Time Commitment: Students, on average, spend over 6 hours in school each day, and homework adds significantly to this time, leaving little room for other activities.

- Impact on Extracurricular Activities: Homework infringes upon time for sports, music, art, and other enriching experiences, which are as crucial as academic courses.

- Stifling Creativity and Self-Discovery: The constant pressure of homework limits opportunities for students to explore their interests and learn new skills independently.

The National Education Association (NEA) and the National PTA (NPTA) recommend a “10 minutes of homework per grade level” standard, suggesting a more balanced approach. However, the reality often far exceeds this guideline, particularly for older students. The impact of this overreach is profound, affecting not just academic performance but also students’ attitudes toward school, their self-confidence, social skills, and overall quality of life.

Furthermore, the intense homework routine’s effectiveness is doubtful, as it can overwhelm students and detract from the joy of learning. Effective learning builds on prior knowledge in an engaging way, but excessive homework in a home setting may be irrelevant and uninteresting. The key challenge is balancing homework to enhance learning without overburdening students, allowing time for holistic growth and activities beyond academics. It’s crucial to reassess homework policies to support well-rounded development.

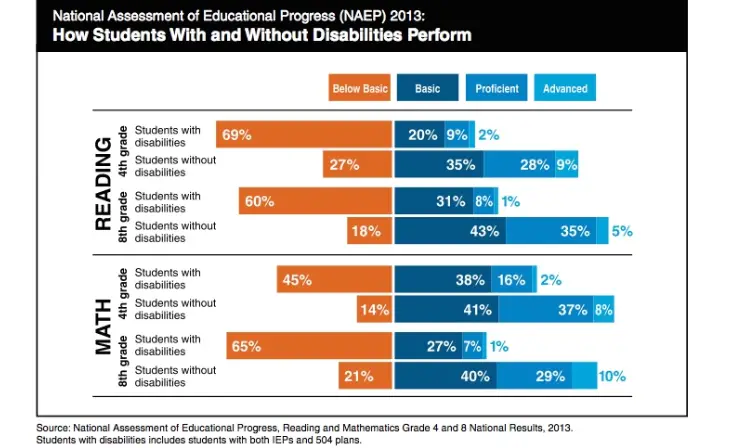

5. Challenges for Students with Learning Disabilities

Homework, a standard educational tool, poses unique challenges for students with learning disabilities, often leading to a frustrating and disheartening experience. These challenges go beyond the typical struggles faced by most students and can significantly impede their educational progress and emotional well-being.

Child psychologist Kenneth Barish’s insights in Psychology Today shed light on the complex relationship between homework and students with learning disabilities:

- Homework as a Painful Endeavor: For students with learning disabilities, completing homework can be likened to “running with a sprained ankle.” It’s a task that, while doable, is fraught with difficulty and discomfort.

- Misconceptions about Laziness: Often, children who struggle with homework are perceived as lazy. However, Barish emphasizes that these students are more likely to be frustrated, discouraged, or anxious rather than unmotivated.

- Limited Improvement in School Performance: The battles over homework rarely translate into significant improvement in school for these children, challenging the conventional notion of homework as universally beneficial.

These points highlight the need for a tailored approach to homework for students with learning disabilities. It’s crucial to recognize that the traditional homework model may not be the most effective or appropriate method for facilitating their learning. Instead, alternative strategies that accommodate their unique needs and learning styles should be considered.

In conclusion, the conventional homework paradigm needs reevaluation, particularly concerning students with learning disabilities. By understanding and addressing their unique challenges, educators can create a more inclusive and supportive educational environment. This approach not only aids in their academic growth but also nurtures their confidence and overall development, ensuring that they receive an equitable and empathetic educational experience.

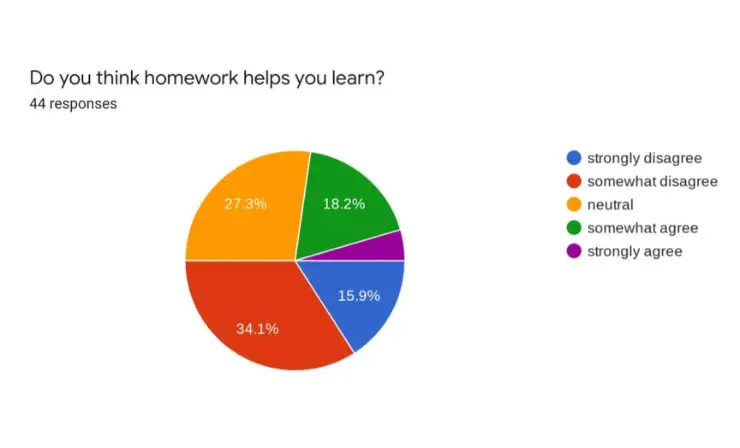

6. Critique of Underlying Assumptions about Learning

The longstanding belief in the educational sphere that more homework automatically translates to more learning is increasingly being challenged. Critics argue that this assumption is not only flawed but also unsupported by solid evidence, questioning the efficacy of homework as an effective learning tool.

Alfie Kohn , a prominent critic of homework, aptly compares students to vending machines in this context, suggesting that the expectation of inserting an assignment and automatically getting out of learning is misguided. Kohn goes further, labeling homework as the “greatest single extinguisher of children’s curiosity.” This critique highlights a fundamental issue: the potential of homework to stifle the natural inquisitiveness and love for learning in children.

The lack of concrete evidence supporting the effectiveness of homework is evident in various studies:

- Marginal Effectiveness of Homework: A study involving 28,051 high school seniors found that the effectiveness of homework was marginal, and in some cases, it was counterproductive, leading to more academic problems than solutions.

- No Correlation with Academic Achievement: Research in “ National Differences, Global Similarities ” showed no correlation between homework and academic achievement in elementary students, and any positive correlation in middle or high school diminished with increasing homework loads.

- Increased Academic Pressure: The Teachers College Record published findings that homework adds to academic pressure and societal stress, exacerbating performance gaps between students from different socioeconomic backgrounds.

These findings bring to light several critical points:

- Quality Over Quantity: According to a recent article in Monitor on Psychology , experts concur that the quality of homework assignments, along with the quality of instruction, student motivation, and inherent ability, is more crucial for academic success than the quantity of homework.

- Counterproductive Nature of Excessive Homework: Excessive homework can lead to more academic challenges, particularly for students already facing pressures from other aspects of their lives.

- Societal Stress and Performance Gaps: Homework can intensify societal stress and widen the academic performance divide.

The emerging consensus from these studies suggests that the traditional approach to homework needs rethinking. Rather than focusing on the quantity of assignments, educators should consider the quality and relevance of homework, ensuring it truly contributes to learning and development. This reassessment is crucial for fostering an educational environment that nurtures curiosity and a love for learning, rather than extinguishing it.

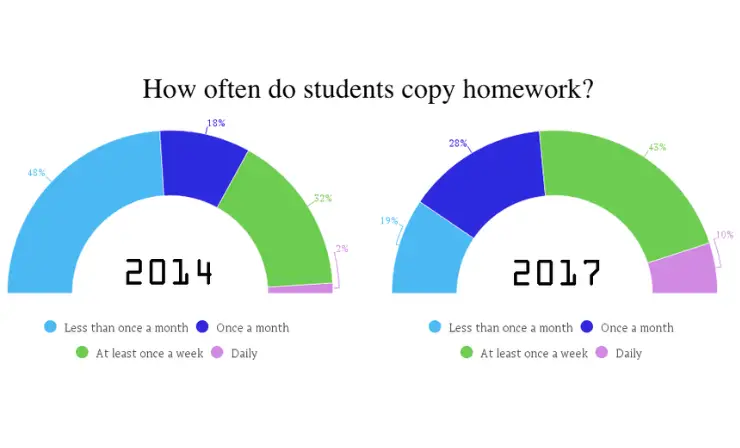

7. Issues with Homework Enforcement, Reliability, and Temptation to Cheat

In the academic realm, the enforcement of homework is a subject of ongoing debate, primarily due to its implications on student integrity and the true value of assignments. The challenges associated with homework enforcement often lead to unintended yet significant issues, such as cheating, copying, and a general undermining of educational values.

Key points highlighting enforcement challenges:

- Difficulty in Enforcing Completion: Ensuring that students complete their homework can be a complex task, and not completing homework does not always correlate with poor grades.

- Reliability of Homework Practice: The reliability of homework as a practice tool is undermined when students, either out of desperation or lack of understanding, choose shortcuts over genuine learning. This approach can lead to the opposite of the intended effect, especially when assignments are not well-aligned with the students’ learning levels or interests.

- Temptation to Cheat: The issue of cheating is particularly troubling. According to a report by The Chronicle of Higher Education , under the pressure of at-home assignments, many students turn to copying others’ work, plagiarizing, or using creative technological “hacks.” This tendency not only questions the integrity of the learning process but also reflects the extreme stress that homework can induce.

- Parental Involvement in Completion: As noted in The American Journal of Family Therapy , this raises concerns about the authenticity of the work submitted. When parents complete assignments for their children, it not only deprives the students of the opportunity to learn but also distorts the purpose of homework as a learning aid.

In conclusion, the challenges of homework enforcement present a complex problem that requires careful consideration. The focus should shift towards creating meaningful, manageable, and quality-driven assignments that encourage genuine learning and integrity, rather than overwhelming students and prompting counterproductive behaviors.

Addressing Opposing Views on Homework Practices

While opinions on homework policies are diverse, understanding different viewpoints is crucial. In the following sections, we will examine common arguments supporting homework assignments, along with counterarguments that offer alternative perspectives on this educational practice.

1. Improvement of Academic Performance

Homework is commonly perceived as a means to enhance academic performance, with the belief that it directly contributes to better grades and test scores. This view posits that through homework, students reinforce what they learn in class, leading to improved understanding and retention, which ultimately translates into higher academic achievement.

However, the question of why students should not have homework becomes pertinent when considering the complex relationship between homework and academic performance. Studies have indicated that excessive homework doesn’t necessarily equate to higher grades or test scores. Instead, too much homework can backfire, leading to stress and fatigue that adversely affect a student’s performance. Reuters highlights an intriguing correlation suggesting that physical activity may be more conducive to academic success than additional homework, underscoring the importance of a holistic approach to education that prioritizes both physical and mental well-being for enhanced academic outcomes.

2. Reinforcement of Learning

Homework is traditionally viewed as a tool to reinforce classroom learning, enabling students to practice and retain material. However, research suggests its effectiveness is ambiguous. In instances where homework is well-aligned with students’ abilities and classroom teachings, it can indeed be beneficial. Particularly for younger students , excessive homework can cause burnout and a loss of interest in learning, counteracting its intended purpose.

Furthermore, when homework surpasses a student’s capability, it may induce frustration and confusion rather than aid in learning. This challenges the notion that more homework invariably leads to better understanding and retention of educational content.

3. Development of Time Management Skills

Homework is often considered a crucial tool in helping students develop important life skills such as time management and organization. The idea is that by regularly completing assignments, students learn to allocate their time efficiently and organize their tasks effectively, skills that are invaluable in both academic and personal life.

However, the impact of homework on developing these skills is not always positive. For younger students, especially, an overwhelming amount of homework can be more of a hindrance than a help. Instead of fostering time management and organizational skills, an excessive workload often leads to stress and anxiety . These negative effects can impede the learning process and make it difficult for students to manage their time and tasks effectively, contradicting the original purpose of homework.

4. Preparation for Future Academic Challenges

Homework is often touted as a preparatory tool for future academic challenges that students will encounter in higher education and their professional lives. The argument is that by tackling homework, students build a foundation of knowledge and skills necessary for success in more advanced studies and in the workforce, fostering a sense of readiness and confidence.

Contrarily, an excessive homework load, especially from a young age, can have the opposite effect . It can instill a negative attitude towards education, dampening students’ enthusiasm and willingness to embrace future academic challenges. Overburdening students with homework risks disengagement and loss of interest, thereby defeating the purpose of preparing them for future challenges. Striking a balance in the amount and complexity of homework is crucial to maintaining student engagement and fostering a positive attitude towards ongoing learning.

5. Parental Involvement in Education

Homework often acts as a vital link connecting parents to their child’s educational journey, offering insights into the school’s curriculum and their child’s learning process. This involvement is key in fostering a supportive home environment and encouraging a collaborative relationship between parents and the school. When parents understand and engage with what their children are learning, it can significantly enhance the educational experience for the child.

However, the line between involvement and over-involvement is thin. When parents excessively intervene by completing their child’s homework, it can have adverse effects . Such actions not only diminish the educational value of homework but also rob children of the opportunity to develop problem-solving skills and independence. This over-involvement, coupled with disparities in parental ability to assist due to variations in time, knowledge, or resources, may lead to unequal educational outcomes, underlining the importance of a balanced approach to parental participation in homework.

Exploring Alternatives to Homework and Finding a Middle Ground

In the ongoing debate about the role of homework in education, it’s essential to consider viable alternatives and strategies to minimize its burden. While completely eliminating homework may not be feasible for all educators, there are several effective methods to reduce its impact and offer more engaging, student-friendly approaches to learning.

Alternatives to Traditional Homework

- Project-Based Learning: This method focuses on hands-on, long-term projects where students explore real-world problems. It encourages creativity, critical thinking, and collaborative skills, offering a more engaging and practical learning experience than traditional homework. For creative ideas on school projects, especially related to the solar system, be sure to explore our dedicated article on solar system projects .

- Flipped Classrooms: Here, students are introduced to new content through videos or reading materials at home and then use class time for interactive activities. This approach allows for more personalized and active learning during school hours.

- Reading for Pleasure: Encouraging students to read books of their choice can foster a love for reading and improve literacy skills without the pressure of traditional homework assignments. This approach is exemplified by Marion County, Florida , where public schools implemented a no-homework policy for elementary students. Instead, they are encouraged to read nightly for 20 minutes . Superintendent Heidi Maier’s decision was influenced by research showing that while homework offers minimal benefit to young students, regular reading significantly boosts their learning. For book recommendations tailored to middle school students, take a look at our specially curated article .

Ideas for Minimizing Homework

- Limiting Homework Quantity: Adhering to guidelines like the “ 10-minute rule ” (10 minutes of homework per grade level per night) can help ensure that homework does not become overwhelming.

- Quality Over Quantity: Focus on assigning meaningful homework that is directly relevant to what is being taught in class, ensuring it adds value to students’ learning.

- Homework Menus: Offering students a choice of assignments can cater to diverse learning styles and interests, making homework more engaging and personalized.