Is it time to get rid of homework? Mental health experts weigh in.

It's no secret that kids hate homework. And as students grapple with an ongoing pandemic that has had a wide range of mental health impacts, is it time schools start listening to their pleas about workloads?

Some teachers are turning to social media to take a stand against homework.

Tiktok user @misguided.teacher says he doesn't assign it because the "whole premise of homework is flawed."

For starters, he says, he can't grade work on "even playing fields" when students' home environments can be vastly different.

"Even students who go home to a peaceful house, do they really want to spend their time on busy work? Because typically that's what a lot of homework is, it's busy work," he says in the video that has garnered 1.6 million likes. "You only get one year to be 7, you only got one year to be 10, you only get one year to be 16, 18."

Mental health experts agree heavy workloads have the potential do more harm than good for students, especially when taking into account the impacts of the pandemic. But they also say the answer may not be to eliminate homework altogether.

Emmy Kang, mental health counselor at Humantold , says studies have shown heavy workloads can be "detrimental" for students and cause a "big impact on their mental, physical and emotional health."

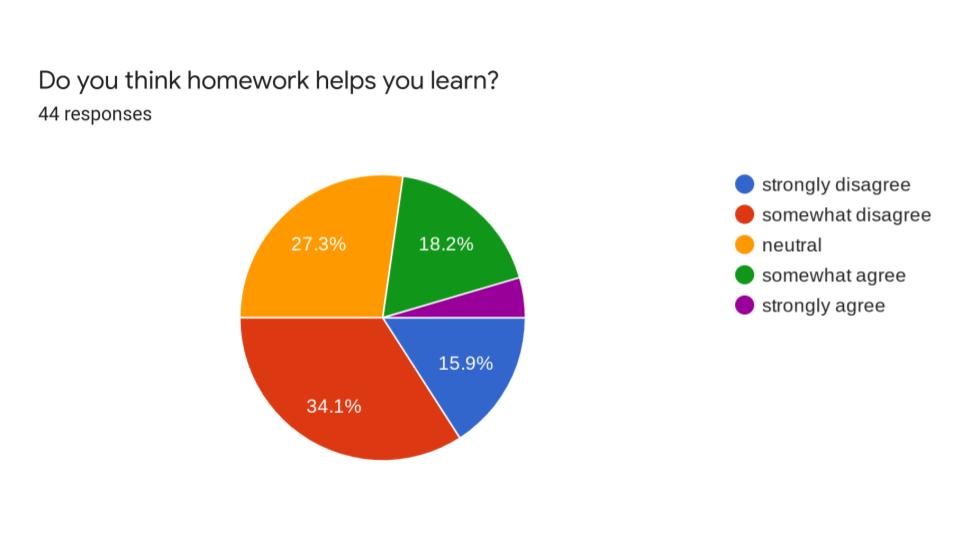

"More than half of students say that homework is their primary source of stress, and we know what stress can do on our bodies," she says, adding that staying up late to finish assignments also leads to disrupted sleep and exhaustion.

Cynthia Catchings, a licensed clinical social worker and therapist at Talkspace , says heavy workloads can also cause serious mental health problems in the long run, like anxiety and depression.

And for all the distress homework can cause, it's not as useful as many may think, says Dr. Nicholas Kardaras, a psychologist and CEO of Omega Recovery treatment center.

"The research shows that there's really limited benefit of homework for elementary age students, that really the school work should be contained in the classroom," he says.

For older students, Kang says, homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night.

"Most students, especially at these high achieving schools, they're doing a minimum of three hours, and it's taking away time from their friends, from their families, their extracurricular activities. And these are all very important things for a person's mental and emotional health."

Catchings, who also taught third to 12th graders for 12 years, says she's seen the positive effects of a no-homework policy while working with students abroad.

"Not having homework was something that I always admired from the French students (and) the French schools, because that was helping the students to really have the time off and really disconnect from school," she says.

The answer may not be to eliminate homework completely but to be more mindful of the type of work students take home, suggests Kang, who was a high school teacher for 10 years.

"I don't think (we) should scrap homework; I think we should scrap meaningless, purposeless busy work-type homework. That's something that needs to be scrapped entirely," she says, encouraging teachers to be thoughtful and consider the amount of time it would take for students to complete assignments.

The pandemic made the conversation around homework more crucial

Mindfulness surrounding homework is especially important in the context of the past two years. Many students will be struggling with mental health issues that were brought on or worsened by the pandemic , making heavy workloads even harder to balance.

"COVID was just a disaster in terms of the lack of structure. Everything just deteriorated," Kardaras says, pointing to an increase in cognitive issues and decrease in attention spans among students. "School acts as an anchor for a lot of children, as a stabilizing force, and that disappeared."

But even if students transition back to the structure of in-person classes, Kardaras suspects students may still struggle after two school years of shifted schedules and disrupted sleeping habits.

"We've seen adults struggling to go back to in-person work environments from remote work environments. That effect is amplified with children because children have less resources to be able to cope with those transitions than adults do," he explains.

'Get organized' ahead of back-to-school

In order to make the transition back to in-person school easier, Kang encourages students to "get good sleep, exercise regularly (and) eat a healthy diet."

To help manage workloads, she suggests students "get organized."

"There's so much mental clutter up there when you're disorganized. ... Sitting down and planning out their study schedules can really help manage their time," she says.

Breaking up assignments can also make things easier to tackle.

"I know that heavy workloads can be stressful, but if you sit down and you break down that studying into smaller chunks, they're much more manageable."

If workloads are still too much, Kang encourages students to advocate for themselves.

"They should tell their teachers when a homework assignment just took too much time or if it was too difficult for them to do on their own," she says. "It's good to speak up and ask those questions. Respectfully, of course, because these are your teachers. But still, I think sometimes teachers themselves need this feedback from their students."

More: Some teachers let their students sleep in class. Here's what mental health experts say.

More: Some parents are slipping young kids in for the COVID-19 vaccine, but doctors discourage the move as 'risky'

- Second Opinion

- Research & Innovation

- Patients & Families

- Health Professionals

- Recently Visited

- Segunda opinión

- Refer a patient

- MyChart Login

Healthier, Happy Lives Blog

Sort articles by..., sort by category.

- Celebrating Volunteers

- Community Outreach

- Construction Updates

- Family-Centered Care

- Healthy Eating

- Heart Center

- Interesting Things

- Mental Health

- Patient Stories

- Research and Innovation

- Safety Tips

- Sustainability

- World-Class Care

About Our Blog

- Back-to-School

- Pediatric Technology

Latest Posts

- Does Your Child Have Strep Throat?

- Giving Children Hearing and Confidence

- Remission Holds Fast After Five Relapses for Young Woman With Leukemia

- Ask Your Family About Heart Disease

- Doctors Remove Highly Complex Brain Tumor Through Toddler’s Nose

Health Hazards of Homework

March 18, 2014 | Julie Greicius Pediatrics .

A new study by the Stanford Graduate School of Education and colleagues found that students in high-performing schools who did excessive hours of homework “experienced greater behavioral engagement in school but also more academic stress, physical health problems, and lack of balance in their lives.”

Those health problems ranged from stress, headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems, to psycho-social effects like dropping activities, not seeing friends or family, and not pursuing hobbies they enjoy.

In the Stanford Report story about the research, Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of the study published in the Journal of Experimental Education , says, “Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good.”

The study was based on survey data from a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in California communities in which median household income exceeded $90,000. Of the students surveyed, homework volume averaged about 3.1 hours each night.

“It is time to re-evaluate how the school environment is preparing our high school student for today’s workplace,” says Neville Golden, MD , chief of adolescent medicine at Stanford Medicine Children’s Health and a professor at the School of Medicine. “This landmark study shows that excessive homework is counterproductive, leading to sleep deprivation, school stress and other health problems. Parents can best support their children in these demanding academic environments by advocating for them through direct communication with teachers and school administrators about homework load.”

Related Posts

Top-ranked group group in Los Gatos, Calif., is now a part of one of the…

The Stanford Medicine Children’s Health network continues to grow with our newest addition, Town and…

- Julie Greicius

- more by this author...

Connect with us:

Download our App:

ABOUT STANFORD MEDICINE CHILDREN'S HEALTH

- Leadership Team

- Vision, Mission & Values

- The Stanford Advantage

- Government and Community Relations

LUCILE PACKARD FOUNDATION FOR CHILDREN'S HEALTH

- Get Involved

- Volunteering Services

- Auxiliaries & Affiliates

- Our Hospital

- Send a Greeting Card

- New Hospital

- Refer a Patient

- Pay Your Bill

Also Find Us on:

- Notice of Nondiscrimination

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Code of Conduct

- Price Transparency

- Stanford Medicine

- Stanford University

- Stanford Health Care

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School's In

- In the Media

You are here

More than two hours of homework may be counterproductive, research suggests.

A Stanford education researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter. "Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good," wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education . The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students' views on homework. Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year. Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night. "The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students' advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being," Pope wrote. Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school. Their study found that too much homework is associated with: • Greater stress : 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor. • Reductions in health : In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems. • Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits : Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were "not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills," according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy. A balancing act The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills. Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as "pointless" or "mindless" in order to keep their grades up. "This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points," said Pope, who is also a co-founder of Challenge Success , a nonprofit organization affiliated with the GSE that conducts research and works with schools and parents to improve students' educational experiences.. Pope said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said. "Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development," wrote Pope. High-performing paradox In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. "Young people are spending more time alone," they wrote, "which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities." Student perspectives The researchers say that while their open-ended or "self-reporting" methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for "typical adolescent complaining" – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe. The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Clifton B. Parker is a writer at the Stanford News Service .

More Stories

⟵ Go to all Research Stories

Get the Educator

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

Improving lives through learning

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

Search form

- Find Stories

- For Journalists

Stanford research shows pitfalls of homework

A Stanford researcher found that students in high-achieving communities who spend too much time on homework experience more stress, physical health problems, a lack of balance and even alienation from society. More than two hours of homework a night may be counterproductive, according to the study.

Education scholar Denise Pope has found that too much homework has negative effects on student well-being and behavioral engagement. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

A Stanford researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter.

“Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good,” wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education .

The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students’ views on homework.

Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year.

Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night.

“The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students’ advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being,” Pope wrote.

Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school.

Their study found that too much homework is associated with:

• Greater stress: 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor.

• Reductions in health: In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems.

• Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits: Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were “not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills,” according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy.

A balancing act

The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills.

Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as “pointless” or “mindless” in order to keep their grades up.

“This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points,” Pope said.

She said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said.

“Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development,” wrote Pope.

High-performing paradox

In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. “Young people are spending more time alone,” they wrote, “which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities.”

Student perspectives

The researchers say that while their open-ended or “self-reporting” methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for “typical adolescent complaining” – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe.

The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Homework Struggles May Not Be a Behavior Problem

Exploring some options to understand and help..

Posted August 2, 2022 | Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

- Mental health challenges and neurodevelopmental differences directly affect children's ability to do homework.

- Understanding what difficulties are getting in the way—beyond the usual explanation of a behavior problem—is key.

- Sleep and mental health needs can take priority over homework completion.

Chelsea was in 10th grade the first time I told her directly to stop doing her homework and get some sleep. I had been working with her since she was in middle school, treating her anxiety disorder. She deeply feared disappointing anyone—especially her teachers—and spent hours trying to finish homework perfectly. The more tired and anxious she got, the harder it got for her to finish the assignments.

One night Chelsea called me in despair, feeling hopeless. She was exhausted and couldn’t think straight. She felt like a failure and that she was a burden to everyone because she couldn’t finish her homework.

She was shocked when I told her that my prescription for her was to go to sleep now—not to figure out how to finish her work. I told her to leave her homework incomplete and go to sleep. We briefly discussed how we would figure it out the next day, with her mom and her teachers. At that moment, it clicked for her that it was futile to keep working—because nothing was getting done.

This was an inflection point for her awareness of when she was emotionally over-cooked and when she needed to stop and take a break or get some sleep. We repeated versions of this phone call several times over the course of her high school and college years, but she got much better at being able to do this for herself most of the time.

When Mental Health Symptoms Interfere with Homework

Kids with mental health or neurodevelopmental challenges often struggle mightily with homework. Challenges can come up in every step of the homework process, including, but not limited to:

- Remembering and tracking assignments and materials

- Getting the mental energy/organization to start homework

- Filtering distractions enough to persist with assignments

- Understanding unspoken or implied parts of the homework

- Remembering to bring finished homework to class

- Being in class long enough to know the material

- Tolerating the fear of not knowing or failing

- Not giving up the assignment because of a panic attack

- Tolerating frustration—such as not understanding—without emotional dysregulation

- Being able to ask for help—from a peer or a teacher and not being afraid to reach out

This list is hardly comprehensive. ADHD , autism spectrum disorder, social anxiety , generalized anxiety, panic disorder, depression , dysregulation, and a range of other neurodevelopmental and mental health challenges cause numerous learning differences and symptoms that can specifically and frequently interfere with getting homework done.

The Usual Diagnosis for Homework Problems is "Not Trying Hard Enough"

Unfortunately, when kids frequently struggle to meet homework demands, teachers and parents typically default to one explanation of the problem: The child is making a choice not to do their homework. That is the default “diagnosis” in classrooms and living rooms. And once this framework is drawn, the student is often seen as not trying hard enough, disrespectful, manipulative, or just plain lazy.

The fundamental disconnect here is that the diagnosis of homework struggles as a behavioral choice is, in fact, only one explanation, while there are so many other diagnoses and differences that impair children's ability to consistently do their homework. If we are trying to create solutions based on only one understanding of the problem, the solutions will not work. More devastatingly, the wrong solutions can worsen the child’s mental health and their long-term engagement with school and learning.

To be clear, we aren’t talking about children who sometimes struggle with or skip homework—kids who can change and adapt their behaviors and patterns in response to the outcomes of that struggle. For this discussion, we are talking about children with mental health and/or neurodevelopmental symptoms and challenges that create chronic difficulties with meeting homework demands.

How Can You Help a Child Who Struggles with Homework?

How can you help your child who is struggling to meet homework demands because of their ADHD, depression, anxiety, OCD , school avoidance, or any other neurodevelopmental or mental health differences? Let’s break this down into two broad areas—things you can do at home, and things you can do in communication with the school.

Helping at Home

The following suggestions for managing school demands at home can feel counterintuitive to parents—because we usually focus on helping our kids to complete their tasks. But mental health needs jump the line ahead of task completion. And starting at home will be key to developing an idea of what needs to change at school.

- Set an end time in the evening after which no more homework will be attempted. Kids need time to decompress and they need sleep—and pushing homework too close to or past bedtime doesn’t serve their educational needs. Even if your child hasn’t been able to approach the homework at all, even if they have avoided and argued the whole evening, it is still important for everyone to have a predictable time to shut down the whole process.

- If there are arguments almost every night about homework, if your child isn’t starting homework or finishing it, reframe it from failure into information. It’s data to put into problem-solving. We need to consider other possible explanations besides “behavioral choice” when trying to understand the problem and create effective solutions. What problems are getting in the way of our child’s meeting homework demands that their peers are meeting most of the time?

- Try not to argue about homework. If you can check your own anxiety and frustration, it can be more productive to ally with your child and be curious with them. Kids usually can’t tell you a clear “why” but maybe they can tell you how they are feeling and what they are thinking. And if your child can’t talk about it or just keeps saying “I don't know,” try not to push. Come back another time. Rushing, forcing, yelling, and threatening will predictably not help kids do homework.

Helping at School

The second area to explore when your neurodiverse child struggles frequently with homework is building communication and connections with school and teachers. Some places to focus on include the following.

- Label your child’s diagnoses and break down specific symptoms for the teachers and school team. Nonjudgmental, but specific language is essential for teachers to understand your child’s struggles. Breaking their challenges down into the problems specific to homework can help with building solutions. As your child gets older, help them identify their difficulties and communicate them to teachers.

- Let teachers and the school team know that your child’s mental health needs—including sleep—take priority over finishing homework. If your child is always struggling to complete homework and get enough sleep, or if completing homework is leading to emotional meltdowns every night, adjusting their homework demands will be more successful than continuing to push them into sleep deprivation or meltdowns.

- Request a child study team evaluation to determine if your child qualifies for services under special education law such as an IEP, or accommodations through section 504—and be sure that homework adjustments are included in any plan. Or if such a plan is already in place, be clear that modification of homework expectations needs to be part of it.

The Long-Term Story

I still work with Chelsea and she recently mentioned how those conversations so many years ago are still part of how she approaches work tasks or other demands that are spiking her anxiety when she finds herself in a vortex of distress. She stops what she is doing and prioritizes reducing her anxiety—whether it’s a break during her day or an ending to the task for the evening. She sees that this is crucial to managing her anxiety in her life and still succeeding at what she is doing.

Task completion at all costs is not a solution for kids with emotional needs. Her story (and the story of many of my patients) make this crystal clear.

Candida Fink, M.D. , is board certified in child/adolescent and general psychiatry. She practices in New York and has co-authored two books— The Ups and Downs of Raising a Bipolar Child and Bipolar Disorder for Dummies.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Homework as a Mental Health Concern It's time for an in depth discussion about homework as a major concern for those pursuing mental health in schools. So many problems between kids and their families, the home and school, and students and teachers arise from conflicts over homework. The topic is a long standing concern for mental health practitioners, especially those who work in schools. Over the years, we have tried to emphasize the idea that schools need to ensure that homework is designed as "motivated practice," and parents need to avoid turning homework into a battleground. These views are embedded in many of the Center documents. At this time, we hope you will join in a discussion of what problems you see arising related to homework and what you recommend as ways to deal with such problems, what positive homework practices you know about, and so forth. Read the material that follows, and then, let us hear from you on this topic. Contact: [email protected] ######################### As one stimulus, here's a piece by Sharon Cromwell from Education World prepared for teachers " The Homework Dilemma: How Much Should Parents Get Involved? " http://www.education-world.com/a_curr/curr053.shtml . What can teachers do to help parents help their children with homework? Just what kind of parental involvement -- and how much involvement -- truly helps children with their homework? The most useful stance parents can take, many experts agree, is to be somewhat but not overly involved in homework. The emphasis needs to be on parents' helping children do their homework themselves -- not on doing it for them. In an Instructor magazine article, How to Make Parents Your Homework Partner s, study-skills consultant Judy Dodge maintains that involving students in homework is largely the teacher's job, yet parents can help by "creating a home environment that's conducive to kids getting their homework done." Children who spend more time on homework, on average, do better academically than children who don't, and the academic benefits of homework increase in the upper grades, according to Helping Your Child With Homework , a handbook by the Office of Education Research and Improvement in the U.S. Department of Education. The handbook offers ideas for helping children finish homework assignments successfully and answers questions that parents and people who care for elementary and junior high school students often ask about homework. One of the Goals 2000 goals involves the parent/school relationship. The goal reads, "Every school will promote partnerships that will increase parental involvement and participation in promoting the social, emotional, and academic growth of children." Teachers can pursue the goal, in part, by communicating to parents their reasons for assigning homework. For example, the handbook states, homework can help children to review and practice what they have learned; prepare for the next day's class; use resources, such as libraries and reference materials; investigate topics more fully than time allows in the classroom. Parents can help children excel at homework by setting a regular time; choosing a place; removing distractions; having supplies and resources on hand; monitoring assignments; and providing guidance. The handbook cautions against actually doing the homework for a child, but talking about the assignment so the child can figure out what needs to be done is OK. And reviewing a completed assignment with a child can also be helpful. The kind of help that works best depends, of course, partly on the child's age. Elementary school students who are doing homework for the first time may need more direct involvement than older students. HOMEWORK "TIPS" Specific methods have been developed for encouraging the optimal parental involvement in homework. TIPS (Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork) Interactive Homework process was designed by researchers at Johns Hopkins University and teachers in Maryland, Virginia, and the District of Columbia to meet parents' and teachers' needs, says the Phi Delta Kappa Research Bulletin . The September 1997 bulletin reported the effects of TIPS-Language Arts on middle-grade students' writing skills, language arts report card grades, and attitudes toward TIPS as well as parents' reactions to interactive homework. TIPS interactive homework assignments involve students in demonstrating or discussing homework with a family member. Parents are asked to monitor, interact, and support their children. They are not required to read or direct the students' assignments because that is the students' responsibility. All TIPS homework has a section for home-to-school communication where parents indicate their interaction with the student about the homework. The goals of the TIPS process are for parents to gain knowledge about their children's school work, students to gain mastery in academic subjects by enhancing school lessons at home, and teachers to have an understanding of the parental contribution to student learning. "TIPS" RESULTS Nearly all parents involved in the TIPS program said TIPS provided them with information about what their children were studying in school. About 90 percent of the parents wanted the school to continue TIPS the following year. More than 80 percent of the families liked the TIPS process (44 percent a lot; 36% a little). TIPS activities were better than regular homework, according to 60 percent of the students who participated. About 70 percent wanted the school to use TIPS the next year. According to Phi Delta Kappa Research Bulletin , more family involvement helped students' writing skills increase, even when prior writing skills were taken into account. And completing more TIPS assignments improved students' language arts grades on report cards, even after prior report card grades and attendance were taken into account. Of the eight teachers involved, six liked the TIPS process and intended to go on using it without help or supplies from the researchers. Furthermore, seven of the eight teachers said TIPS "helps families see what their children are learning in class." OTHER TIPS In "How to Make Parents Your Homework Partners," Judy Dodge suggests that teachers begin giving parent workshops to provide practical tips for "winning the homework battle." At the workshop, teachers should focus on three key study skills: Organizational skills -- Help put students in control of work and to feel sure that they can master what they need to learn and do. Parents can, for example, help students find a "steady study spot" with the materials they need at hand. Time-management skills -- Enable students to complete work without feeling too much pressure and to have free time. By working with students to set a definite study time, for example, parents can help with time management. Active study strategies -- Help students to achieve better outcomes from studying. Parents suggest, for instance, that students write questions they think will be on a test and then recite their answers out loud. Related Resources Homework Without Tears by Lee Canter and Lee Hauser (Perennial Library, 1987). A down-to-earth book by well-known experts suggests how to deal with specific homework problems. Megaskills: How Families Can Help Children Succeed in School and Beyond by Dorothy Rich (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1992). Families can help children develop skills that nurture success in and out of school. "Helping Your Student Get the Most Out of Homework" by the National PTA and the National Education Association (1995). This booklet for teachers to use with students is sold in packages of 25 through the National PTA. The Catalog item is #B307. Call 312-549-3253 or write National PTA Orders, 135 South LaSalle Street, Dept. 1860, Chicago, IL 60674-1860. Related Sites A cornucopia of homework help is available for children who use a computer or whose parents are willing to help them get started online. The following LINKS include Internet sites that can be used for reference, research, and overall resources for both homework and schoolwork. Dr. Internet. The Dr. Internet Web site, part of the Internet Public Library, helps students with science and math homework or projects. It includes a science project resource guide Help With Homework. His extensive listing of Internet links is divided into Language Art Links, Science Links, Social Studies Links, Homework Help, Kids Education, and Universities. If students know what they are looking for, the site could be invaluable. Kidz-Net... Links to places where you can get help with homework. An array of homework help links is offered here, from Ask Dr. Math (which provides answers to math questions) to Roget's Thesaurus and the White House. Surfing the Net With Kids: Got Questions? Links to people -- such as teachers, librarians, experts, authors, and other students -- who will help students with questions about homework. Barbara J. Feldman put together the links. Kidsurfer: For Kids and Teens The site, from the National Children's Coalition, includes a Homework/Reference section for many subjects, including science, geography, music, history, and language arts. Homework: Parents' Work, Kid's Work, or School Work? A quick search of this title in the Education Week Archives and you'll find an article presenting a parent's viewpoint on helping children with homework. @#@#@#@@# As another stimulus for the discussion, here is an excerpt from our online continuing education module Enhancing Classroom Approaches for Addressing Barriers to Learning ( https://smhp.psych.ucla.edu ) Turning Homework into Motivated Practice Most of us have had the experience of wanting to be good at something such as playing a musical instrument or participating in a sport. What we found out was that becoming good at it meant a great deal of practice, and the practicing often was not very much fun. In the face of this fact, many of us turned to other pursuits. In some cases, individuals were compelled by their parents to labor on, and many of these sufferers grew to dislike the activity. (A few, of course, commend their parents for pushing them, but be assured these are a small minority. Ask your friends who were compelled to practice the piano.) Becoming good at reading, mathematics, writing, and other academic pursuits requires practice outside the classroom. This, of course, is called homework. Properly designed, homework can benefit students. Inappropriately designed homework, however, can lead to avoidance, parent-child conflicts, teacher reproval, and student dislike of various arenas of learning. Well-designed homework involves assignments that emphasize motivated practice. As with all learning processes that engage students, motivated practice requires designing activities that the student perceives as worthwhile and doable with an appropriate amount of effort. In effect, the intent is to personalize in-class practice and homework. This does not mean every student has a different practice activity. Teachers quickly learn what their students find engaging and can provide three or four practice options that will be effective for most students in a class. The idea of motivated practice is not without its critics. I don't doubt that students would prefer an approach to homework that emphasized motivated practice. But �� that's not preparing them properly for the real world. People need to work even when it isn't fun, and most of the time work isn't fun. Also, if a person wants to be good at something, they need to practice it day in and day out, and that's not fun! In the end, won't all this emphasis on motivation spoil people so that they won't want to work unless it's personally relevant and interesting? We believe that a great deal of learning and practice activities can be enjoyable. But even if they are not, they can be motivating if they are viewed as worthwhile and experienced as satisfying. At the same time, we do recognize that there are many things people have to do in their lives that will not be viewed and experienced in a positive way. How we all learn to put up with such circumstances is an interesting question, but one for which psychologists have yet to find a satisfactory answer. It is doubtful, however, that people have to experience the learning and practice of basic knowledge and skills as drudgery in order to learn to tolerate boring situations. Also in response to critics of motivated practice, there is the reality that many students do not master what they have been learning because they do not pursue the necessary practice activities. Thus, at least for such individuals, it seems essential to facilitate motivated practice. Minimally, facilitating motivated practice requires establishing a variety of task options that are potentially challenging -- neither too easy nor too hard. However, as we have stressed, the processes by which tasks are chosen must lead to perceptions on the part of the learner that practice activities, task outcomes, or both are worthwhile -- especially as potential sources of personal satisfaction. The examples in the following exhibit illustrate ways in which activities can be varied to provide for motivated learning and practice. Because most people have experienced a variety of reading and writing activities, the focus here is on other types of activity. Students can be encouraged to pursue such activity with classsmates and/or family members. Friends with common interests can provide positive models and support that can enhance productivity and even creativity. Research on motivation indicates that one of the most powerful factors keeping a person on a task is the expectation of feeling some sense of satisfaction when the task is completed. For example, task persistence results from the expectation that one will feel smart or competent while performing the task or at least will feel that way after the skill is mastered. Within some limits, the stronger the sense of potential outcome satisfaction, the more likely practice will be pursued even when the practice activities are rather dull. The weaker the sense of potential outcome satisfaction, the more the practice activities themselves need to be positively motivating. Exhibit � Homework and Motivated Practice Learning and practicing by (1) doing using movement and manipulation of objects to explore a topic (e.g., using coins to learn to add and subtract) dramatization of events (e.g., historical, current) role playing and simulations (e.g., learning about democratic vs. autocratic government by trying different models in class; learning about contemporary life and finances by living on a budget) actual interactions (e.g., learning about human psychology through analysis of daily behavior) applied activities (e.g., school newspapers, film and video productions, band, sports) actual work experience (e.g., on-the-job learning) (2) listening reading to students (e.g., to enhance their valuing of literature) audio media (e.g., tapes, records, and radio presentations of music, stories, events) listening games and activities (e.g., Simon Says; imitating rhymes, rhythms, and animal sounds) analyzing actual oral material (e.g., learning to detect details and ideas in advertisements or propaganda presented on radio or television, learning to identify feelings and motives underlying statements of others) (3) looking directly observing experts, role models, and demonstrations visual media visual games and activities (e.g., puzzles, reproducing designs, map activities) analyzing actual visual material (e.g., learning to find and identify ideas observed in daily events) (4) asking information gathering (e.g., investigative reporting, interviewing, and opinion sampling at school and in the community) brainstorming answers to current problems and puzzling questions inquiry learning (e.g., learning social studies and science by identifying puzzling questions, formulating hypotheses, gathering and interpreting information, generalizing answers, and raising new questions) question-and-answer games and activities (e.g., twenty questions, provocative and confrontational questions) questioning everyday events (e.g., learning about a topic by asking people about how it effects their lives) O.K. That's should be enough to get you going. What's your take on all this? What do you think we all should be telling teachers and parents about homework? Let us hear from you ( [email protected] ). Back to Hot Topic Home Page Hot Topic Home Page --> Table of Contents Home Page Search Send Us Email School Mental Health Project-UCLA Center for Mental Health in Schools WebMaster: Perry Nelson ([email protected])

When Is Homework Stressful? Its Effects on Students’ Mental Health

Are you wondering when is homework stressful? Well, homework is a vital constituent in keeping students attentive to the course covered in a class. By applying the lessons, students learned in class, they can gain a mastery of the material by reflecting on it in greater detail and applying what they learned through homework.

However, students get advantages from homework, as it improves soft skills like organisation and time management which are important after high school. However, the additional work usually causes anxiety for both the parents and the child. As their load of homework accumulates, some students may find themselves growing more and more bored.

Students may take assistance online and ask someone to do my online homework . As there are many platforms available for the students such as Chegg, Scholarly Help, and Quizlet offering academic services that can assist students in completing their homework on time.

Negative impact of homework

There are the following reasons why is homework stressful and leads to depression for students and affect their mental health. As they work hard on their assignments for alarmingly long periods, students’ mental health is repeatedly put at risk. Here are some serious arguments against too much homework.

No uniqueness

Homework should be intended to encourage children to express themselves more creatively. Teachers must assign kids intriguing assignments that highlight their uniqueness. similar to writing an essay on a topic they enjoy.

Moreover, the key is encouraging the child instead of criticizing him for writing a poor essay so that he can express himself more creatively.

Lack of sleep

One of the most prevalent adverse effects of schoolwork is lack of sleep. The average student only gets about 5 hours of sleep per night since they stay up late to complete their homework, even though the body needs at least 7 hours of sleep every day. Lack of sleep has an impact on both mental and physical health.

No pleasure

Students learn more effectively while they are having fun. They typically learn things more quickly when their minds are not clouded by fear. However, the fear factor that most teachers introduce into homework causes kids to turn to unethical means of completing their assignments.

Excessive homework

The lack of coordination between teachers in the existing educational system is a concern. As a result, teachers frequently end up assigning children far more work than they can handle. In such circumstances, children turn to cheat on their schoolwork by either copying their friends’ work or using online resources that assist with homework.

Anxiety level

Homework stress can increase anxiety levels and that could hurt the blood pressure norms in young people . Do you know? Around 3.5% of young people in the USA have high blood pressure. So why is homework stressful for children when homework is meant to be enjoyable and something they look forward to doing? It is simple to reject this claim by asserting that schoolwork is never enjoyable, yet with some careful consideration and preparation, homework may become pleasurable.

No time for personal matters

Students that have an excessive amount of homework miss out on personal time. They can’t get enough enjoyment. There is little time left over for hobbies, interpersonal interaction with colleagues, and other activities.

However, many students dislike doing their assignments since they don’t have enough time. As they grow to detest it, they can stop learning. In any case, it has a significant negative impact on their mental health.

Children are no different than everyone else in need of a break. Weekends with no homework should be considered by schools so that kids have time to unwind and prepare for the coming week. Without a break, doing homework all week long might be stressful.

How do parents help kids with homework?

Encouraging children’s well-being and health begins with parents being involved in their children’s lives. By taking part in their homework routine, you can see any issues your child may be having and offer them the necessary support.

Set up a routine

Your student will develop and maintain good study habits if you have a clear and organized homework regimen. If there is still a lot of schoolwork to finish, try putting a time limit. Students must obtain regular, good sleep every single night.

Observe carefully

The student is ultimately responsible for their homework. Because of this, parents should only focus on ensuring that their children are on track with their assignments and leave it to the teacher to determine what skills the students have and have not learned in class.

Listen to your child

One of the nicest things a parent can do for their kids is to ask open-ended questions and listen to their responses. Many kids are reluctant to acknowledge they are struggling with their homework because they fear being labelled as failures or lazy if they do.

However, every parent wants their child to succeed to the best of their ability, but it’s crucial to be prepared to ease the pressure if your child starts to show signs of being overburdened with homework.

Talk to your teachers

Also, make sure to contact the teacher with any problems regarding your homework by phone or email. Additionally, it demonstrates to your student that you and their teacher are working together to further their education.

Homework with friends

If you are still thinking is homework stressful then It’s better to do homework with buddies because it gives them these advantages. Their stress is reduced by collaborating, interacting, and sharing with peers.

Additionally, students are more relaxed when they work on homework with pals. It makes even having too much homework manageable by ensuring they receive the support they require when working on the assignment. Additionally, it improves their communication abilities.

However, doing homework with friends guarantees that one learns how to communicate well and express themselves.

Review homework plan

Create a schedule for finishing schoolwork on time with your child. Every few weeks, review the strategy and make any necessary adjustments. Gratefully, more schools are making an effort to control the quantity of homework assigned to children to lessen the stress this produces.

Bottom line

Finally, be aware that homework-related stress is fairly prevalent and is likely to occasionally affect you or your student. Sometimes all you or your kid needs to calm down and get back on track is a brief moment of comfort. So if you are a student and wondering if is homework stressful then you must go through this blog.

While homework is a crucial component of a student’s education, when kids are overwhelmed by the amount of work they have to perform, the advantages of homework can be lost and grades can suffer. Finding a balance that ensures students understand the material covered in class without becoming overburdened is therefore essential.

Zuella Montemayor did her degree in psychology at the University of Toronto. She is interested in mental health, wellness, and lifestyle.

Psychreg is a digital media company and not a clinical company. Our content does not constitute a medical or psychological consultation. See a certified medical or mental health professional for diagnosis.

- Privacy Policy

© Copyright 2014–2034 Psychreg Ltd

- PSYCHREG JOURNAL

- MEET OUR WRITERS

- MEET THE TEAM

The effects of homework on students' social-emotional health

Files and links (1).

Cookie Preference Center

Your preferences, strictly necessary cookies.

As described in our Corporate Privacy Notice and Cookie Policy , we use cookies (including pixels or other similar technologies) on our websites, mobile applications and related products (the “services”). The types of cookies we use are described below.

These are cookies necessary for the services to function and are always active. They are usually only set in response to actions made by the user which amount to a request for services, such as setting privacy preferences, logging in, or filling in forms.

Cookie List

Does Homework Affect Mental Health?

Homework can be a source of frustration and stress for students, but how does it affect their mental health? As studies into this area continue to gather evidence, it is clear that there is a correlation between homework and mental health. In this article, we will explore the potential impacts of homework on students’ mental health, from the perspectives of both students and educators.

Yes, homework can affect mental health. It can lead to feelings of stress, frustration and even anger. Too much homework can also lead to sleep deprivation, which can have a negative impact on mental health. It’s important to balance homework with other activities such as exercise, spending time with family and friends, and participating in hobbies.

The Relationship Between Homework and Time Management

How to manage homework and mental health, the role of schools and parents, the impact of technology, can too much homework harm your child’s health, does homework impact mental health.

Homework can be a difficult task for students, especially when they are overwhelmed with the amount of work they have to complete. It is important to consider how homework impacts the mental health of students. While there is no single answer to this question, research suggests that homework can have a negative effect on mental health. Studies have found that students who spend a lot of time on homework have higher levels of stress and anxiety, as well as lower levels of academic performance.

One of the most common negative effects of homework on mental health is stress. Students who have too much homework can become overwhelmed, leading to feelings of frustration, hopelessness, and helplessness. This can lead to increased levels of stress, which can have a negative impact on mental health. Furthermore, stress can lead to difficulty concentrating, difficulty sleeping, and decreased motivation.

Another way that homework can negatively impact mental health is through academic performance. Research has found that students who spend too much time on homework have lower grades and are less likely to complete their assignments. This can lead to a decrease in self-esteem, as students may feel like they are not capable of achieving their academic goals. It can also lead to an increase in anxiety, as students may feel like they are not able to keep up with their peers.

Time management is an important skill for any student, and it can be difficult to manage when there is a lot of homework to complete. Students who have too much homework may find that they do not have enough time to complete their assignments, leading to feelings of frustration and helplessness. This can lead to poor time management skills, which can have a negative impact on mental health.

Furthermore, when students have too much homework, it can lead to procrastination. This can be a problem because it can lead to an inability to focus and get tasks done, which can have a negative impact on mental health. Poor time management skills can also lead to an inability to prioritize tasks, which can have a negative effect on overall performance.

It is important for students to find ways to manage their homework and mental health. One way to do this is to break up assignments into smaller chunks. This can help students to focus on one task at a time, which can reduce stress and anxiety. Additionally, students should try to take breaks while completing assignments, as this can help them to stay focused and motivated.

Furthermore, it is important for students to set realistic goals when it comes to completing their homework. Setting realistic goals can help students to stay motivated and can help them to avoid feeling overwhelmed. Additionally, students should try to find ways to make their homework more enjoyable, such as working with a friend or listening to music.

Schools and parents can also play an important role in helping students manage their homework and mental health. Schools can provide students with resources and support to help them manage their workload. Parents can also provide support and guidance to help students manage their workload. Additionally, both schools and parents can help students to set realistic goals and to develop good time management skills.

Technology can also have a positive impact on mental health when it comes to homework. Many students use technology to help them complete their assignments more quickly and efficiently. Additionally, technology can help students to stay organized and motivated. For example, many students use online calendars and to-do lists to help them keep track of their assignments.

Overall, homework can have a negative impact on mental health, but there are ways to manage this impact. Students should strive to find ways to make their homework more manageable, such as breaking up assignments into smaller chunks and setting realistic goals. Additionally, schools and parents can provide support and guidance to help students manage their workload. Finally, technology can be used to help students stay organized and motivated.

Related Faq

Q1: What is the purpose of homework? A1: Homework is typically assigned to students by their teachers as a way to review and practice the material learned in class. It is meant to reinforce the skills and knowledge taught in class and to help students develop good study habits, critical thinking, and problem solving skills.

Q2: What are the potential positive effects of doing homework? A2: Doing homework can potentially have positive effects on a student’s mental health. It can help to improve a student’s self-esteem and confidence by allowing them to practice their skills and gain a sense of accomplishment when completing their homework correctly. It can also help to reduce stress and anxiety by allowing students to work at their own pace and in the comfort of their own home.

Q3: What are the potential negative effects of doing homework? A3: The potential negative effects of doing homework can include an increase in stress and anxiety levels due to the pressure of completing assignments in a limited amount of time. It can also lead to feelings of frustration and dissatisfaction if a student is unable to complete the assignment correctly or quickly enough. Additionally, excessive amounts of homework can lead to a lack of sleep and decreased physical activity, both of which can contribute to mental health issues.

Q4: How can parents help their children manage their homework-related stress? A4: Parents can help their children manage their homework-related stress by creating a supportive environment in which their children feel comfortable and safe asking for help. Additionally, parents can ensure their children have a balanced schedule by limiting the amount of time spent on homework and encouraging physical activity and other activities. They can also help by providing a quiet, well-lit work area and allowing their children to break up their assignments into smaller tasks to make them seem more manageable.

Q5: How can teachers help their students manage their homework-related stress? A5: Teachers can help their students manage their homework-related stress by providing clear instructions and expectations for assignments. They can also ensure that the amount of homework assigned is appropriate for the student’s age and ability level. Additionally, teachers can provide resources for students who may need extra help, such as additional tutoring or study groups.

Q6: Is there a correlation between homework and poor mental health? A6: While there is no definitive answer to this question, there is evidence to suggest that excessive amounts of homework can be detrimental to a student’s mental health. Studies have found that too much homework can lead to increased stress and anxiety levels, as well as decreased physical activity levels. Additionally, it can lead to a lack of sleep, which can also have a negative effect on mental health.

The answer to the question of whether or not homework affects mental health is a resounding yes. Homework can have a positive effect on mental health when managed in a balanced and reasonable way, but when taken to extremes, it can become a source of stress, anxiety, and depression. The key is to ensure that homework is assigned in moderation and that students have the support they need to manage it. With the right balance, homework can help students build problem-solving skills, increase their confidence, and provide an opportunity to practice time management.

About The Author

Ronald Rivera

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The Enlightened Mindset

Exploring the World of Knowledge and Understanding

Welcome to the world's first fully AI generated website!

The Impact of Homework on Student Mental Health

By Happy Sharer

Introduction

Homework is a key part of the educational process. It is often seen as an essential part of learning and helping students to develop important skills. However, there is growing evidence that too much homework can have a negative effect on student mental health. This article will explore the impact of homework on student mental health, examining the correlation between workload and stress levels, analyzing the effects of too much homework on student anxiety, and understanding how homework can lead to depression in students.

Exploring the Impact of Homework on Student Mental Health

Homework has long been seen as an important part of the educational process, but it can also become a source of stress for students. A recent study by the American Psychological Association found that more than two-thirds of students reported feeling overwhelmed by their homework load. The study also found that students who felt overwhelmed were more likely to experience symptoms of depression and anxiety. It is clear that the amount of homework assigned to students can have a significant impact on their mental health.

Examining the Correlation Between Homework and Student Stress Levels

The amount of homework assigned to students can have a direct impact on their stress levels. Too much homework can lead to feelings of frustration and overwhelm, which can then lead to increased stress levels. A study published in the journal Developmental Psychology found that when students had more homework assignments, they experienced higher levels of stress. The study also found that students who had more homework assignments were more likely to report feeling overwhelmed and anxious.

It is also important to consider the relationship between homework and academic performance. Studies have suggested that too much homework can lead to decreased academic performance, which can then lead to increased stress levels. A study published in the Journal of Experimental Education found that when students had more homework, their performance on tests was lower than those with less homework. This suggests that too much homework can lead to increased stress levels, as students feel pressure to perform at a higher level.

In order to reduce homework-related stress, it is important for students to prioritize their work. Planning ahead and breaking down tasks into smaller, more manageable chunks can help students to feel more organized and in control. Taking regular breaks throughout the day can also help students to stay focused and motivated. Finally, it is important to ensure that students are getting enough sleep in order to maintain their energy levels and reduce stress.

Analyzing the Effects of Too Much Homework on Student Anxiety

Too much homework can also lead to increased anxiety levels in students. A study published in the journal Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review found that when students had more homework, they were more likely to experience symptoms of anxiety. The study also found that students with excessive amounts of homework were more likely to report feeling overwhelmed and unable to cope with the workload.

It is important to understand the psychological effects of too much homework on students. Excessive amounts of homework can lead to feelings of frustration and helplessness, which can then lead to increased anxiety levels. Furthermore, students may start to see homework as a burden rather than an opportunity to learn, which can lead to decreased motivation and further feelings of anxiety.

In order to reduce homework-related anxiety, it is important to set realistic goals and expectations. Setting achievable goals and deadlines can help students to stay focused and motivated. It is also important to ensure that students are getting enough rest and taking regular breaks throughout the day. Finally, it is important to talk to teachers and parents about any concerns or worries that students may have about their workload.

Understanding How Homework Can Lead to Depression in Students

Too much homework can also lead to depression in students. A study published in the journal Pediatrics found that when students had more homework, they were more likely to experience symptoms of depression. The study also found that students with excessive amounts of homework were more likely to report feeling overwhelmed, frustrated, and helpless.

It is important to understand the psychological effects of too much homework on students. Excessive amounts of homework can lead to feelings of hopelessness and failure, which can then lead to increased depression levels. Furthermore, students may start to see homework as a chore rather than an opportunity to learn, which can lead to decreased motivation and further feelings of depression.

In order to reduce homework-related depression, it is important to focus on developing positive coping skills. Taking time to relax and practice mindfulness can help students to manage their emotions and stay focused. It is also important to ensure that students are getting enough sleep and taking regular breaks throughout the day. Finally, it is important to talk to teachers and parents about any concerns or worries that students may have about their workload.

Investigating the Relationship Between Homework and Student Self-Esteem

Finally, it is important to consider the relationship between homework and student self-esteem. A study published in the journal Developmental Psychology found that when students had more homework, they were more likely to report feeling inadequate and inferior. The study also found that students with excessive amounts of homework were more likely to report feeling overwhelmed and helpless.

It is important to understand the psychological effects of too much homework on students. Excessive amounts of homework can lead to feelings of worthlessness and failure, which can then lead to decreased self-esteem. Furthermore, students may start to see homework as a burden rather than an opportunity to learn, which can lead to decreased motivation and further feelings of inadequacy.

In order to increase homework-related self-esteem, it is important to focus on developing positive self-talk. Taking time to recognize achievements and celebrate successes can help students to stay motivated and build confidence. It is also important to ensure that students are getting enough rest and taking regular breaks throughout the day. Finally, it is important to talk to teachers and parents about any concerns or worries that students may have about their workload.

In conclusion, it is clear that the amount of homework assigned to students can have a significant impact on their mental health. Too much homework can lead to increased stress levels, anxiety, depression, and decreased self-esteem. It is therefore important to ensure that students are not overloaded with homework and are given the opportunity to learn in a healthy environment. By reducing the amount of homework assigned to students, we can help them to develop important skills without compromising their mental wellbeing.

(Note: Is this article not meeting your expectations? Do you have knowledge or insights to share? Unlock new opportunities and expand your reach by joining our authors team. Click Registration to join us and share your expertise with our readers.)

Hi, I'm Happy Sharer and I love sharing interesting and useful knowledge with others. I have a passion for learning and enjoy explaining complex concepts in a simple way.

Related Post

Jack hanna keto gummies: real reviews, price, how much exercise does a border collie need a comprehensive guide, a comprehensive guide to the ornish diet: reshaping your health and well-being, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Expert Guide: Removing Gel Nail Polish at Home Safely

Trading crypto in bull and bear markets: a comprehensive examination of the differences, making croatia travel arrangements, make their day extra special: celebrate with a customized cake.

- How It Works

- Sleep Meditation

- VA Workers and Veterans

- How It Works 01

- Sleep Meditation 02

- Mental Fitness 03

- Neurofeedback 04

- Healium for Business 05

- VA Workers and Veterans 06

- Sports Meditation 07

- VR Experiences 08

- Social Purpose 11

Does Homework Cause Stress? Exploring the Impact on Students’ Mental Health

How much homework is too much?

Jump to: The Link Between Homework and Stress | Homework’s Impact on Mental Health | Benefits of Homework | How Much Homework Should Teacher’s Assign? | Advice for Students | How Healium Helps

Homework has become a matter of concern for educators, parents, and researchers due to its potential effects on students’ stress levels. It’s no secret that students often find themselves grappling with high levels of stress and anxiety throughout their academic careers, so understanding the extent to which homework affects those stress levels is important.

By delving into the latest research and understanding the underlying factors at play, we hope to provide valuable insights for educators, parents, and students who are wondering about how much stress homework is causing in their lives.

The Link Between Homework and Stress: What the Research Says

Over the years, numerous studies have been conducted to investigate the relationship between homework and stress levels in students.

One study published in the Journal of Experimental Education found that students who reported spending more than two hours per night on homework experienced higher stress levels and physical health issues . Those same students reported over three hours of homework a night on average.

This study, conducted by Stanford lecturer Denise Pope, has been heavily cited throughout the years, with WebMD even producing the below video on the topic– part of their special report series on teens and stress :

Additional studies published by Sleep Health Journal found that long hours on homework on may be a risk factor for depression while also suggesting that reducing workload outside of class may benefit sleep and mental fitness .

Lastly, a study presented by Frontiers in Psychology highlighted significant health implications for high school students facing chronic stress, including emotional exhaustion and alcohol and drug use.

Overall, it appears clear that the answer to whether or not homework is a significant stressor for students is “Yes, depending on the workload assigned to students.” As such, teachers and parents alike should be wary of how much work they are truly putting on the shoulders of teenagers.

Homework’s Impact on Mental Health and Well-being

Homework-induced stress on students is far-reaching and involves both psychological and physiological side effects.

1. Potential Psychological Effects of Homework-Induced Stress:

• Anxiety: The pressure to perform academically and meet homework expectations can lead to heightened levels of anxiety in students. Constant worry about completing assignments on time and achieving high grades can be overwhelming.

• Sleep Disturbances : Homework-related stress can disrupt students’ sleep patterns, leading to sleep anxiety or sleep deprivation, both of which can negatively impact cognitive function and emotional regulation.

• Reduced Motivation: Excessive homework demands can drain students’ motivation, causing them to feel fatigued and disengaged from their studies. Reduced motivation may lead to a lack of interest in learning, hindering overall academic performance.

2. Potential Physical Effects of Homework-Induced Stress:

• Impaired Immune Function: Prolonged stress can weaken the immune system, making students more susceptible to illnesses and infections.

• Disrupted Hormonal Balance : The body’s stress response triggers the release of hormones like cortisol, which, when chronically elevated due to stress, can disrupt the delicate hormonal balance and lead to various health issues.

• Gastrointestinal Disturbances: Stress has been known to affect the gastrointestinal system, leading to symptoms such as stomachaches, nausea, and other digestive problems.

• Cardiovascular Impact: The increased heart rate and elevated blood pressure associated with stress can strain the cardiovascular system, potentially increasing the risk of heart-related issues in the long run.

• Brain impact: Prolonged exposure to stress hormones may impact the brain’s functioning , affecting memory, concentration, and cognitive abilities.

The Benefits of Homework

It’s important to note that homework also offers many benefits that contribute to students’ academic growth and development, such as:

• Development of Time Management Skills: Completing homework within specified deadlines encourages students to manage their time efficiently. This valuable skill extends beyond academics and becomes essential in various aspects of life.

• Preparation for Future Challenges : Homework helps prepare students for future academic challenges and responsibilities. It fosters a sense of discipline and responsibility, qualities that are crucial for success in higher education and professional life.

• Enhanced Problem-Solving Abilities: Homework often presents students with challenging problems to solve. Tackling these problems independently nurtures critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

However, while homework can foster discipline, time management, and self-directed learning, it is crucial to strike a balance that promotes both academic growth and mental well-being .

How Much Homework Should Teachers Assign?

As a general guideline, educators should consider assigning a workload that allows students to grasp concepts effectively without overwhelming them . Quality over quantity is key, ensuring that homework assignments are purposeful, relevant, and targeted towards specific objectives.

Advice for Students: How to balance Homework and Well-being

Finding a balance between academic responsibilities and well-being is crucial for students. Here are some practical tips and techniques to help manage homework-related stress and foster a healthier approach to learning:

• Effective Time Management : Encourage students to create a structured study schedule that allocates sufficient time for homework, breaks, and other activities. Prioritizing tasks and setting realistic goals can prevent last-minute rushes and reduce the feeling of being overwhelmed.

• Break Tasks into Smaller Chunks : Large assignments can be daunting and may contribute to stress. Students should break such tasks into smaller, manageable parts. This approach not only makes the workload seem less intimidating but also provides a sense of accomplishment as each section is completed.