Home — Essay Samples — Entertainment — Video Games — Video Games Should Be Banned

Video Games Should Be Banned

- Categories: Video Games

About this sample

Words: 759 |

Published: Mar 14, 2024

Words: 759 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Entertainment

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 1116 words

1 pages / 464 words

4 pages / 2022 words

5 pages / 2604 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Video Games

Can video games make you smarter is a question that has sparked considerable interest and debate in recent years. Video games, once regarded solely as a form of entertainment, have evolved into complex interactive experiences [...]

The realm of competitive gaming, known as esports, has swiftly emerged as a global phenomenon that transcends traditional sports and entertainment. The advantages of esports reach far beyond the virtual arena, impacting [...]

Why videogames are good for you is a question that has sparked debate and curiosity in recent years. Video gaming, once associated solely with entertainment, has emerged as a multifaceted phenomenon that encompasses cognitive, [...]

Video games have become an integral part of modern society, with millions of people across the globe engaging in gaming activities. Despite the widespread popularity of video games, they are often criticized for their negative [...]

One of the ideas that the twenty-first century has brought to us is a new form of play and how often we as individuals associate it with technology. But why do we associate it with technology and what is that reason? Our [...]

With video games becoming increasingly violent throughout the years, the controversy of whether or not they cause children to become more violent has increased as well, however this statement has yet to be proven. Many people [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Should Video Games Be Banned?

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

Are you looking to showcase your brand in front of the gaming industry’s top leaders? Learn more about GamesBeat Summit sponsorship opportunities here .

Over the last 40 years from their inception video games have been very popular among children and young people. More recently the market has vastly grown becoming a major media industry with new releases poised to create as much revenue as the Hollywood blockbuster films. The UK is the fourth largest developer of video games in the world with the industry employing over 22,000 people. Despite these success stories many people are uncomfortable with video games believing them to be harmful to our societies. Both sides of the argumenthave valid points which merit consideration.

Video games are often condemned because many feel they contain excessive amounts of violence and how this can affect the player. This debate is controversial and the most persistent question when discussing video games. Advocates say games such as the 18-rated Grand Theft Auto series with its high level of violent game play and graphic portrayal of it are unacceptable and should not be sold as it could be damaging to children’s development if they play it. Others try to remind them that this type of game is highly regulated and purchasing is restricted to those over the age of 18. If children play it, that is their parents decision based on their child’s level of maturity and personality. There is a barrier in place to protect younger gamers; it is a matter of parents following the rules.Those against banning the games also cite how other forms of media such as comic books, films and even books were prejudiced against. It is a rite of passage which all forms of media have to go through in order to be generally accepted in society. In the 1940s and 1950s comic books were looked upon as immoral and as causing terrible damage to children. Eventually these thoughts were quelled and now comic books are widely enjoyed around the world. Rap and R&B music is also criticised with some people claiming it incites black youths to take up arms and join gangs while in fact studies have shown the main purchaser of this type of music is white people.

Many people believe video games can be extremely artistic and beautiful. An example of these artistic games is Shadow of the Colossus . The game world is a desolate world in which the player travels battling huge beings known as Colossi to save a young girls life. In many sections of the game the player travels alone. The art helps portray a feeling of loneliness and despair while the orchestral music playing while battling the Colossi depicts a sense of heroism and grandeur. Every component of this game complements each other creating a cohesive experience which is known to bring gamers to tears while playing. This is used as a prime example as a reason why video games shouldn’t be banned and in fact should be embraced by society.

Shadow of the Colossus is seen as a landmark interactive experience

Excessive use of video games has been covered greatly in the last five years by themedia. Cases of technological addiction are often children not knowing when enough is enough but others such as Lee Seung Seop’s have went to the extremes. His case shows how some people are affected by certain video games addictive quality to the extent of playing to death. In 2005 Seop visited an internet cafe in Taegu, South Korea and played Starcraft continuously for fifty hours before suffering cardiac arrest. It was reported that six weeks prior he had broken up with his girlfriend over the issue and had been fired from his job due to “repeated tardiness”. People against video games will say that this case clearly shows the need for them to be banned as they can destroy lives. On the pro-video game side they believe this is an isolated incident involving a severely disturbed individual. Many people believe that people who become addicted to games and become reclusive say those people weren’t very social to begin with video games just filled a gap. People who are social to begin with won’t let games affect their social lives.

Very Addicting

Video games are commonly used in a medical capacity around the world. A study carried out by the American Physical Therapy Association showed that the Nintendo Wii with its motion sensing capabilities could be beneficial in the treatment of teenagers with cerebral palsy. Games are also used in many children’s wards as something to help children feel more comfortable while in hospital. Many medical professionals now believe games to be key to a quick recovery for children. Charities such as Child’s Play donate video game related equipment to hospitals making a difference in sick children’s lives. Professionals such as Jen Usinger at The Children’s Hospital at Legacy Emanuel in Oregon, USA say video games give the patients in the hospital an escape from all the medicine, allowing them to feel like a normal child. Surgeons also use video games with specialised equipment to improve technique and learn new procedures in non life threatening situations. These simulators are specially built and the vast majority of surgeons believe they allow for better patient care. Personally during my work experience at the Royal Alexandra Hospital I practiced on an endoscopic simulator and within an hour from going with no experience at all I could successfully complete an operation. If video games were banned advances in this type of technology, while not completely halted, would’ve been considerably hindered.

RapeLay is a Japanese developed game which has been heavily criticised since its release in 2006. In this you play as a man who stalks a mother and two daughters with the intent to rape them. The game features an in-depth sex simulator in which later in the game the player can tie the three women up and have forced intercourse. Many people were horrified when this game was released and called for its banning, deeming it immoral and extremely offensive to women. Online stores such as Amazon.com have since banned this game and an independent Japanese rating board have restricted the sale and production of RapeLay making it impossible to buy. Some people however have defended the game saying rape is a lesser crime than murder so why should RapeLay be banned while thousands of other legal adult games feature large amounts of killing. Others have also referred to this kind of content being in books and films and they aren’t banned. The reaction to this is video games are interactive while films are passively used.

The Byron Report on video games and internet use with children was released in March, 2008 by the British clinical psychologist Tanya Byron. In relation to video games the report shows that parents are often unclear about classification systems such as PEGI (Pan European Game Information) and how to restrict their child’s access to inappropriate digital media. It also talks about the benefits of video games to youths in the form of learning new skills. Research has shown skills such as reaction times, strategic planning and special perception are greatly improved compared to non-gamers. It also helps improve their planning skills and their willingness to try new methods instead of being afraid to try a different hypothesis. This is due to the player having to process new information quickly and react fast. The report also talks about how video games can help relax the player and how gaming has evolved from a solitary activity into a form of entertainment the whole family can enjoy together. This helps social development and creates stronger bonds with parents and siblings than an activity such as watching television would form. The Byron report also affirms doctor’s theories that video games can help with recovery after a painful treatment. Their study showed that those playing video games needed fewer painkillers. It is suggested in the report that video games take up the attention in the brain which would previously have been used focusing on the pain.

Family Friendly Gaming

Overall both sides of the argument have convincing points. Personally I feel video games do a lot more good than bad in modern society. I think it is an overreaction to the problem to ban all games, even those such as Tiger Wood’s Golf and Football Manager which are non-violent and family friendly There are suitable regulations in place to protect younger generations and to police what kind of content is available. One of the biggest issues is parents not being aware of these systems and not knowing what is suitable for their children although I feel these problems will go away over the next 20 years as those who grew up playing games start to have their own children and can protect them from inappropriate content

Stay in the know! Get the latest news in your inbox daily

By subscribing, you agree to VentureBeat's Terms of Service.

Thanks for subscribing. Check out more VB newsletters here .

An error occured.

What do you think? Leave a respectful comment.

Christopher J. Ferguson, The Conversation Christopher J. Ferguson, The Conversation

- Copy URL https://www.pbs.org/newshour/science/analysis-why-its-time-to-stop-blaming-video-games-for-real-world-violence

Analysis: Why it’s time to stop blaming video games for real-world violence

In the wake of the El Paso shooting on Aug. 3 that left 21 dead and dozens injured, a familiar trope has reemerged: Often, when a young man is the shooter, people try to blame the tragedy on violent video games and other forms of media.

This time around, Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick placed some of the blame on a video game industry that “ teaches young people to kill .” Republican House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy of California went on to condemn video games that “dehumanize individuals” as a “problem for future generations.” And President Trump pointed to society’s “glorification of violence,” including “ gruesome and grisly video games .”

These are the same connections a Florida lawmaker made after the Parkland shooting in February 2018, suggesting that the gunman in that case “was prepared to pick off students like it’s a video game .”

Kevin McCarthy, the GOP House minority leader, also tells Fox News that video games are the problem following the mass shootings in El Paso and Dayton. pic.twitter.com/w7DmlJ9O1K — John Whitehouse (@existentialfish) August 4, 2019

But, speaking as a researcher who has studied violent video games for almost 15 years, I can state that there is no evidence to support these claims that violent media and real-world violence are connected. As far back as 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that research did not find a clear connection between violent video games and aggressive behavior.

Criminologists who study mass shootings specifically refer to those sorts of connections as a “ myth .” And in 2017, the Media Psychology and Technology division of the American Psychological Association released a statement I helped craft, suggesting reporters and policymakers cease linking mass shootings to violent media, given the lack of evidence for a link.

A history of a moral panic

So why are so many policymakers inclined to blame violent video games for violence? There are two main reasons.

The first is the psychological research community’s efforts to market itself as strictly scientific. This led to a replication crisis instead, with researchers often unable to repeat the results of their studies. Now, psychology researchers are reassessing their analyses of a wide range of issues – not just violent video games, but implicit racism , power poses and more.

The other part of the answer lies in the troubled history of violent video game research specifically.

An attendee dressed as a Fortnite character poses for a picture in a costume at Comic Con International in San Diego, California, U.S., July 19, 2019. Photo by REUTERS/Mike Blake

Beginning in the early 2000s, some scholars, anti-media advocates and professional groups like the APA began working to connect a methodologically messy and often contradictory set of results to public health concerns about violence. This echoed historical patterns of moral panic, such as 1950s concerns about comic books and Tipper Gore’s efforts to blame pop and rock music in the 1980s for violence, sex and satanism.

Particularly in the early 2000s, dubious evidence regarding violent video games was uncritically promoted . But over the years, confidence among scholars that violent video games influence aggression or violence has crumbled .

Reviewing all the scholarly literature

My own research has examined the degree to which violent video games can – or can’t – predict youth aggression and violence. In a 2015 meta-analysis , I examined 101 studies on the subject and found that violent video games had little impact on kids’ aggression, mood, helping behavior or grades.

Two years later, I found evidence that scholarly journals’ editorial biases had distorted the scientific record on violent video games. Experimental studies that found effects were more likely to be published than studies that had found none. This was consistent with others’ findings . As the Supreme Court noted, any impacts due to video games are nearly impossible to distinguish from the effects of other media, like cartoons and movies.

Any claims that there is consistent evidence that violent video games encourage aggression are simply false.

Spikes in violent video games’ popularity are well-known to correlate with substantial declines in youth violence – not increases. These correlations are very strong, stronger than most seen in behavioral research. More recent research suggests that the releases of highly popular violent video games are associated with immediate declines in violent crime, hinting that the releases may cause the drop-off.

The role of professional groups

With so little evidence, why are people like Kentucky Gov. Matt Bevin still trying to blame violent video games for mass shootings by young men? Can groups like the National Rifle Association seriously blame imaginary guns for gun violence?

A key element of that problem is the willingness of professional guild organizations such as the APA to promote false beliefs about violent video games. (I’m a fellow of the APA.) These groups mainly exist to promote a profession among news media, the public and policymakers, influencing licensing and insurance laws . They also make it easier to get grants and newspaper headlines. Psychologists and psychology researchers like myself pay them yearly dues to increase the public profile of psychology. But there is a risk the general public may mistake promotional positions for objective science.

In 2005 the APA released its first policy statement linking violent video games to aggression. However, my recent analysis of internal APA documents with criminologist Allen Copenhaver found that the APA ignored inconsistencies and methodological problems in the research data.

The APA updated its statement in 2015, but that sparked controversy immediately: More than 230 scholars wrote to the group asking it to stop releasing policy statements altogether. I and others objected to perceived conflicts of interest and lack of transparency tainting the process.

It’s bad enough that these statements misrepresent the actual scholarly research and misinform the public. But it’s worse when those falsehoods give advocacy groups like the NRA cover to shift blame for violence onto non-issues like video games. The resulting misunderstanding hinders efforts to address mental illness and other issues, such as the need for gun control, that are actually related to gun violence.

This article was originally published in The Conversation. Read the original article . This story was updated from an earlier version to reflect the events surrounding the El Paso and Dayton shootings.

Christopher J. Ferguson is a professor of psychology at Stetson University. He's coauthor of " Moral Combat: Why the War on Violent Video Games is Wrong ."

Support Provided By: Learn more

Educate your inbox

Subscribe to Here’s the Deal, our politics newsletter for analysis you won’t find anywhere else.

Thank you. Please check your inbox to confirm.

El Paso shooting is domestic terrorism, investigators say

Nation Aug 04

To Play or Not to Play: The Great Debate About Video Games

Two recent studies shed light on whether video games are good or bad for kids.

With more than 90 percent of American kids playing video games for an average of two hours a day, whether that's a good idea is a valid question for parents to ask. Video games, violent ones especially, have caused such concern that the issue of whether the sale or rental of such games to children should be prohibited was brought before the Supreme Court.

In 2011, the Supreme Court ruled that video games, like plays, movies and books, qualify for First Amendment protection. “Video games,” the court declared, “communicate ideas – and even social messages.” But that didn’t stop the debate. Real-life tragedies continue to bring attention to the subject, like the revelation that the Sandy Hook Elementary School gunman was an avid video game player . Parents seeking an easy answer to whether video games are good or bad won’t find one, and two recent studies illustrate why.

While many studies have made a connection between violent video games and aggression in adolescents, research published in August in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology found that teens who played mature-rated violent video games were also more likely to engage in drug and alcohol use, dangerous driving and risky sexual behavior.

[Read: Read More, Play More: Simple Steps to Success for Today’s Children .]

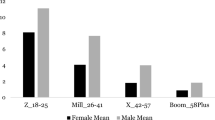

Researchers evaluated more than 5,000 male and female teenagers between ages 13 and 18 over the course of four years and discovered that those who played violent video games were more rebellious and eager to take risks. The effect was greatest among those who played the most as well as those who played games with antisocial main characters.

But a study published in August in Pediatrics of nearly 5,000 girls and boys ages 10 to 15 revealed that children who played video games for less than an hour a day were better adjusted than children who either played no video games or played for three or more hours a day. These children were found to have fewer emotional problems and less hyperactivity, and they were more sociable overall. Video games, the study suggests, play a very small part in children’s lives when compared to such influences as a child’s family, school relationships and economic background.

So are video games harmful to children? “It depends on the content of the game and the outcome of interest,” says Marina Krcmar, an associate professor of communication at Wake Forest University. “Violent games have been found to be associated with aggressive outcomes, increases in hostility and aggressive cognitions.” There are several factors that may explain this.

[Read: 7 Facts About Child Life Specialists .]

First, there are no negative consequences for bad behavior. Players are rewarded for violence with points, reaching a higher level or obtaining more weapons. And, Krcmar adds, players actively commit violence rather than passively watch it, as they may do through other mediums such as movies and television.

“Another issue is that our daily behaviors and interactions actually change our brains – that’s why we encourage kids to study and read," Krcmar says. Research presented at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America in 2011 examined the neurological activity of a group of men who did not typically play violent video games but did so for the study over the course of one week, while a control group played none. MRI scans revealed that those who played the violent video games had less activity in the brain areas involved in controlling emotion and aggressive behavior. The control group showed no brain changes at all. “Keep in mind that these were players randomly assigned to play the games, not players who actively chose to do so,” Krcmar says. “We can’t argue here that people who seek out violent games are more aggressive to begin with.”

The disadvantage of video games, other experts point out, is the simple fact that time spent playing them is time not spent doing such activities as reading a book, playing outside or engaging with friends. But that’s not to say all video games are bad. There are positives to consider, too.

“Video game play is associated with improvements in hand-eye coordination, faster reaction times, improved visuospatial skill and peripheral awareness, while some educational games can also improve math, spelling and reading skills,” Krcmar says.

[Read: How Your TV Is Making You Sick .]

A report published in the January issue of American Psychologist points out that shooter games, where split-second decision-making and attention to rapid change is necessary, can improve cognitive performance, while all genres of video games enhance problem-solving skills. And despite the belief that it’s a socially isolating activity, one survey found that more than 70 percent of people who play video games do so with a friend, either cooperatively or competitively.

“Video games are a wonderful teaching tool,” says Brad Bushman, professor of communication and psychology at The Ohio State University. Computer scientists from the University of California–San Diego recently revealed that children ages 8 to 12 who played a video game they developed that teaches how to code – for either four hours over four weeks or 10 hours over seven days – were successfully able to write code by hand in Java.

So what should parents do? Monitor content and the amount of time spent on video games, Krcmar advises. And Bushman warns that you shouldn't let your children play age-inappropriate video games. “Video games rated M for 'mature audience 17 and older' should not be played by children under 17," he says. And remember: “The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends no more than two hours of entertainment screen time per day for children 2 to 17, and no screen time for children under 2," Bushman says. This applies to video games as well.

Tags: video games , television , children's health , parenting

Most Popular

health disclaimer »

Disclaimer and a note about your health ».

Your Health

A guide to nutrition and wellness from the health team at U.S. News & World Report.

You May Also Like

Eggs: health benefits and recipes.

Janet Helm March 22, 2024

Best Anti-Cancer Foods

Ruben Castaneda and Heidi Godman March 22, 2024

Brain Health Benefits of Seafood

Kelly LeBlanc March 21, 2024

Colon Cancer Diet

Ruben Castaneda and Shanley Chien March 20, 2024

Tylenol, Advil or Aleve: Which Is Best?

Vanessa Caceres March 18, 2024

Health Benefits and Recipes for Beans

Janet Helm March 15, 2024

Best Workouts for Women Over 50

Cedric X. Bryant March 14, 2024

Stress-Relieving Exercises

Stacey Colino March 12, 2024

What Is Bed Rotting?

Claire Wolters March 12, 2024

Worst Foods for Gut Health

Ruben Castaneda and Elaine K. Howley March 12, 2024

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/65110218/GettyImages_1157206935.0.jpg)

Filed under:

The frustrating, enduring debate over video games, violence, and guns

We asked players, parents, developers, and experts to weigh in on how to change the conversation around gaming.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: The frustrating, enduring debate over video games, violence, and guns

In the wake of two mass shootings earlier this month in El Paso, Texas, and Dayton, Ohio, the societal role of video games grabbed a familiar media spotlight. The El Paso shooter briefly referenced Call of Duty , a wildly popular game in which players assume the roles of soldiers during historical and fictional wartime, in his “manifesto.” And just this small mention of the video game seemed to have prompted President Donald Trump to return to a theme he’s emphasized before when looking to assign greater blame for violent incidents.

“We must stop the glorification of violence in our society,” he said in an August 5 press conference. “This includes the gruesome and grisly video games that are now commonplace. It is too easy today for troubled youth to surround themselves with a culture that celebrates violence.”

Trump’s statement suggesting a link between video games and real-world violence echoed sentiments shared by other lawmakers following the back-to-back mass shootings. It’s a response that major media outlets and retailers have also adopted of late; ESPN recently chose to delay broadcasting an esports tournament because of the shootings — a decision that seems to imply the network believes in a link between gaming and real-world violence. And Walmart made a controversial decision to temporarily remove all video game displays from its stores, even as it continues to openly sell guns.

But many members of the public, as well as researchers and some politicians, have counterargued that blaming video games sidesteps the real issue at the root of America’s mass shooting problem: a need for stronger gun control . The frenzied debate over video games within the larger conversation around gun violence underscores both how intense the fight over gun control has become and how easily games can become mired in political rhetoric.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19100040/GettyImages_937382242.jpg)

But this isn’t a new development; blaming video games for real-world violence — any kind of real-world violence — is a longstanding cultural and political habit whose origins date back to the 1970s. It’s also arguably part of a larger recurring wave of concern over any pop culture that’s been perceived as morally deviant, from rock ’n’ roll to the occult , depending on the era. But as mass shootings continue to occur nationwide and attempts to stop them by enacting gun control legislature remain divisive, video games have again become an easy target.

The most recent clamor arose from a clash among several familiar foes. In one corner: politicians like Trump who cite video games as evidence of immoral and violent media’s negative societal impact. In another: people who play video games and resist this reading, while also trying to lodge separate critiques of violence within gaming. In another: scientists at odds over whether there are factual and causal links between video games and real-world violence. And in still another: members of the general public who, upon receiving alarmist messages about games from politicians and the news media, react with yet more alarm.

Subscribe to Today, Explained

Looking for a quick way to keep up with the never-ending news cycle? Host Sean Rameswaram will guide you through the most important stories at the end of each day.

Subscribe on Apple Podcasts , Spotify , Ove r cast , or wherever you listen to podcasts.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19104938/VOX_todayexplained_twitter_profilephoto_1.png)

What is new, however, is that recent criticism of the narrative that video games lead to real-world violence seems particularly intensified, and it’s coming not just from gamers but also from scientists , some media outlets , even mass shooting survivors: David Hogg, who became a gun control advocate after surviving the 2018 mass shooting in Parkland, Florida, unveiled a new March for Our Lives gun control initiative in August, pointedly stating in his announcement on Twitter, “We know video games aren’t to blame.”

And on all sides is a sense that frustration is growing because so little has changed since the last time we had this debate — and since the time before that and the time before that.

There’s no science proving a link between video games and real-world violence. But that hasn’t quelled a debate that’s raged for decades.

Historically, video games have played a verifiable role in a handful of mass shootings, but the science linking video games to gun violence is murky . A vast body of psychology research, most of it conducted before 2015, argues strenuously that video games can contribute to increases in aggression . Yet much of this research has been contested by newer, contradictory findings from both psychologists and scholars in different academic fields. For example, Nickie Phillips , a criminologist whose research deals with violence in popular media, told me that “most criminologists are dismissive of a causal link between media and crime,” and that they’re instead interested in questions of violence as a social construct and how that contributes to political discourse.

That type of research, she stressed, is likely to be less flashy and headline-grabbing than psychology studies, which are more focused on pointing to direct behaviors and their causes. “Social meanings of crime are in transition,” Phillips said. “There’s not a single variable. As a public, we want a single concrete explanation as to why people commit atrocities, when the answers can be very complex.”

The debate over the science is easy to wade into, but it obscures just how preoccupied America is with dangerous media. The oldest moral panic over a video game may be the controversy over a 1976 game called Death Race , which awarded players points for driving over fleeing pedestrians dubbed “gremlins.” The game became mired in controversy, even sparking a segment on 60 Minutes . Interestingly, other games of the era that framed their mechanics through wartime violence, like the 1974 military game Tank , failed to cause as much public concern.

In his 2017 book Moral Combat: Why the War on Violent Video Games Is Wrong , psychologist Patrick Markey points out that before concerned citizens fixated on video games, many of them were worried about arcades — not because of the games they contained, but because they were licentious hangouts for teens. (Insert “ Ya Got Trouble ” here.) By the 1980s, “Arcades were being shut down across the nation by activist parents intent on protecting their children from the dangerous influences lurking within these neon-drenched dungeons,” Markey writes.

Then came the franchise that evolved arcade panic into gameplay panic: Midway Games’ Mortal Kombat , infamous for its gory “fatality” moves . With its 1992 arcade debut, Mortal Kombat sparked hysteria among concerned adults that led to a 1993 congressional hearing and the creation of the Entertainment Software Rating Board, or ESRB . The fighting game franchise still incites debate with every new release.

“Like people were really going to go out and rip people’s spines out,” Cypheroftyr , a gaming critic who typically goes by her internet handle, told me over the phone regarding the mainstream anxiety around Mortal Kombat in the 1990s. Cypheroftyr is an avid player of shooter games and other action games and the founder of the nonprofit I Need Diverse Games .

“I’m old enough to remember the whole Jack Thompson era of trying to say video games are violent and they should be banned,” she said, referencing the infamous disbarred obscenity lawyer known for a strident crusade against games and other media that has spanned decades .

Cypheroftyr pointed out that after the Columbine shooting in April 1999, politicians “were trying to blame both video games and Marilyn Manson. It just feels like this is too easy a scapegoat.”

Politicians have long seized on the idea that recreational fantasy and fictional media have an influence on real-world evil. In 2007, for example, Sen. Mitt Romney (R–UT) blamed “music and movies and TV and video games” for being full of “pornography and violence,” which he argued had influenced the Columbine shooters and, later, the 2007 Virginia Tech shooter.

Video games seem especially prone to garnering political attention in the wake of a tragedy — especially first-person shooters like Call of Duty. A stereotype of a mass shooter, isolated and perpetually consuming graphic violent content, seems to linger in the public’s consciousness. A neighbor of the 2018 Parkland shooter, for instance, told the Miami Herald that the shooter would play video games for up to 12 to 15 hours a day — and although that anecdotal report was unverified, it was still widely circulated.

A 2015 Pew study of 2,000 US adults found that even though 49 percent of adult Americans play video games, 40 percent of Americans also believe in a link between games and violence — specifically, that “people who play violent video games are more likely to be violent themselves.” Additionally, 32 percent of the people who told Pew they play video games also said they believe gaming contributes to an increase in aggression, even though their own experience as, presumably, nonviolent gamers would offer at least some evidence to the contrary.

One person who sees a correlation between violent games and a propensity for real-world violence is Tim Winter . Winter is the president of the Parents Television Council , a nonpartisan advocacy group that lobbies the entertainment industry against marketing graphic violence to children. He spent several years overseeing MGM’s former video game publishing division, MGM Interactive, and moved into advocacy when he became a parent. Growing up, his children played all kinds of video games, except for those he considered too graphic or violent.

In a phone interview, Winter told me his view aligns with the research supporting links between games and aggression.

“Anyone who uses the term ‘moral panic’ in my view is trying to diminish a bona fide conversation that needs to take place,” Winter said. “It’s a simple PR move to refute something that might actually have some value in the broader conversation.”

During our conversation, he compared the connection between violent media and harmful real-world effects to that between cigarettes and lung cancer. If you consume in moderation, he argues, you’ll probably be fine; but, over time, exposure to violent media can have “a cumulative negative effect.” (In fact, studies of infrequent smokers have shown that their risk of coronary disease is roughly equal to that of frequent smokers, and their risk of cancer is still significantly higher than that of nonsmokers.)

“What I believe to be true is that the media we consume has a very powerful impact on shaping our belief structure, our cognitive development, our values, and our opinions,” he said.

He added that it would be foolish to point to any one act of violence and say it was caused by any one video game — that, he argued, “would be like saying lung cancer was caused by that one specific cigarette I smoked.”

“But if you are likely to smoke packs a day over the course of many years, it has a cumulative negative effect on your health,” he continued. “I believe based on the research on both sides that that’s the prevailing truth.”

The debate endures because gun control isn’t being addressed — and games are an easy target

Like many people I spoke with for this story, Winter believes that the debate about gun violence has remained largely at a standstill since Columbine, while the number of mass shootings nationwide has continued to increase.

“If you look at the broader issue of gun violence in America, you have a number of organizations and constituencies pointing at different causes,” he said. “When you look back at what those arguments are, it’s the same arguments that have been made going back to Columbine. Whether it’s gun control, whether it’s mental illness, whether it’s violence in media culture — whatever the debate is about those three root causes, very little progress has been made on any of them.”

The glorification of violence is so culturally embedded in American media through TV, film, games, books, and practically every other available medium that there seems to be very little impetus to change anything about America’s gun culture. We can define “ gun culture ” here as the addition of an embrace of gun ownership and a nationwide oversupply of guns to what Phillips described as “ a culture of violence ” — one in which violence “becomes our go-to way of solving problems — whether that’s individual violence, police violence, state violence.”

“There’s a commodification of violence,” she said, “and we have to understand what that means.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19100050/GettyImages_142837932.jpg)

Naomi Clark , an independent game developer and co-chair of New York University’s Game Center program, agreed. “I find it more plausible that America’s long-standing culture of gun violence has affected video games, as a form of culture, than the other way around,” she told me in an email. “After all, this nation’s cultural traditions and attachments around guns are far older than video games.”

In light of incidents like Walmart’s removal of video game displays after the recent mass shootings while continuing to advertise guns, the connection between the shootings and America’s continued valorization of guns feels extremely stark. “We could ban video games tomorrow and mass shootings would still happen,” Cypheroftyr told me.

“What’s new about the current debate is that the scapegoat of videogaming has never been more nakedly exposed for what it is,” gaming sociologist Katherine Cross wrote in an email, “with Republicans and conservatives manifestly fearful of blaming systematic white supremacism, Trump’s rhetoric, or our nation’s permissive and freewheeling gun culture for the recent rash of terrorism.”

Because of the sensitivity around the issue of gun control, it’s easy for politicians to score points with constituents by focusing a conversation on games and sidestepping other action. “Politicians often blame video games because they are a safe target,” Moral Combat author Markey told me in an email. “There isn’t a giant video game lobby like other potential causes of mass shootings (like the NRA [National Rifle Association]). So [by targeting games], a politician can make it appear they are doing something without risking losing any votes.”

And the general public is often susceptible to this rhetoric, both because it’s emotional and because it may feed what they think they already know about games — even if that’s not a lot. “The narrative that violence in video games contributes to the gun violence in America is, I think, a good example of a bad idea that seems right to people who don’t look too closely at the facts,” Zak Garriss , a video game writer and designer who’s worked on a wide range of games, told me in an email.

“Video games are a global industry, dwarfing other entertainment industries in revenue in markets comprised of gamers from the UK, Germany, France, Japan, the US, and basically anywhere there’s electricity. Yet the spree shooting phenomenon seems to be seriously and uniquely a US issue right now. It’s also worth noting that the ratings systems across these countries vary, and in the case of Europe, are often more liberal in many regards than the US system,” Garriss said.

He also pointed out that this conversation frequently overshadows the important, innovative work that many games are engaged in. “Games like Stardew Valley , Minecraft , or Journey craft experiences that help people relax, detox after a day, bond with friends,” he said. “Games like Papers, Please , That Dragon Cancer , or Life Is Strange interrogate the harder and the darker elements of the human experience like love, grief, loneliness, and death.”

In other words, a conversation that focuses on games and guns alone dismisses the vital cultural role that video games play as art. “Play video games and you can jump on giant mushrooms, shoot a wizard on the moon, grow a farm, fall in love, experience nearly infinite worlds really,” Garriss told me. “If games have a unifying organizing principle, I’d say it’s to delight. The pursuit of fun.”

He continued: “To me, the tragedy, if there is one, in the current discourse around video games and violence, lies in failing to see the magic happening in the play. As devs, it’s a magic we’re chasing with every game. And as players, I think it’s a magic that has not just the potential but the actual power to bring people together, to aid mental health, to make us think, to help us heal. And to experience delight.”

But for some members of the public, games’ recreational, relaxational, and artistic values might be another thing that make them suspect. “If they don’t play games or ‘aged out of it,’ they might see them as frivolous or a waste of time,” Cypheroftyr says. “It’s easy to go, ‘Oh, you’re still playing video games? Why are you wasting your life?’”

That idea — that video games are a waste of time — is another longstanding element of cultural assumptions around games of all kinds, Clark, the game developer, told me. “Games have been an easy target in every era because there’s something inherently unproductive or even anti-productive about them, and so there’s also a long history of game designers trying to rehabilitate games and make them ‘do work’ or provide instruction.”

All of this makes it incredibly easy to fixate on video games instead of addressing difficult but more relevant targets, like NRA funding and easy access to guns. And that, in turn, makes it a complicated proposition to extricate video games from conversations about gun violence, let alone limit the conversation around violent games to people who might actually be in a position to create change, like the people who make the games in the first place.

Yet what’s striking when you drill down into the community around gaming is how many gamers agree with many of the arguments politicians are making. As a fan of shooter games, Cypheroftyr told me she routinely plays violent games like Call of Duty and the military action role-playing game (RPG) The Division . “I’m not out here trying to murder people,” she stressed. But like the Parents Television Council’s Winter, Cypheroftyr and many of the other people I spoke with agree that the gaming industry needs to do a lot more to examine the at times shocking imagery it perpetuates.

Many members of the gaming community are already discussing game violence

Multiple people I spoke with expressed frustration that the conversation about video games’ role in mass shootings is obscuring another, very important conversation to be had within the gaming community about violent games.

Clark told me that the public’s lack of nuance and an insistence on a binary reading of the issue is part of the problem. “Most people are capable of understanding that causes are complex,” she said, “that you can’t just point to one thing and say, ‘This is mostly or entirely to blame!’”

But she also cautioned that the gaming community’s reactionary defensiveness to this lack of nuance also prevents many video game fans from acknowledging that games do play a role within a violent culture. “That complexity cuts both ways,” she told me. “Even though it’s silly to say that ‘games cause violence,’ it’s also just as silly to say that games have nothing to do with a culture that has a violence problem.”

That culture is endemic to the gaming industry, added Justin Carter, a freelance journalist whose work focuses on video games and culture.

“The industry does have a fetishization of guns and violence,” Carter said. “You look at games like Borderlands or Destiny and one of the selling points is how many guns there are.” The upcoming first-person shooter game Borderlands 3 , he pointed out, boasts “over a billion” different guns from its 12 fictional weapons manufacturers , all of which tout special perks to get players to try their guns. These perks serve as marketing both inside and outside the game; the game’s publisher, 2K Games, invites players to exult in violence using language that speaks for itself :

Deliver devastating critical hits to enemies’ soft-and-sensitives, then joy-puke as your bullets ricochet towards other targets. ... Step 1: Hit your enemies with tracker tags. Step 2: Unleash a hail of Smart Bullets that track towards your targets. Step 3: Loot! Deal guaranteed elemental damage with your finger glued to the trigger ...

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/18955912/BorderlandsBoxArt.jpg)

“There are very few [action/adventure] games that give you options other than murdering people,” Cypheroftyr said. “Games don’t do enough to show the other side of it. You shoot someone, you die, they die, you reset, you reload, and nothing happens.”

“I know that if I shoot people in a game it’s not real,” she added. “99.9 percent of people don’t need to be told that. I’m not playing out a power fantasy or anything, but I’ve become more aware of how most games [that] use violence [do so] to solve problems.”

An insistence from game developers on blithely ignoring the potential political messages of their games is another frustration for her. “All these game makers are like, there’s no politics in the game. There’s no message. And I’m like ... did you just send me through a war museum and you’re telling me this?!”

The game Cypheroftyr is referencing is The Division 2 , which features a section where players can engage in enemy combat during a walkthrough of a Vietnam War memorial museum. While she loves the game, she told me the fact that players use weapons from the Vietnam War era while in a war museum belies game developers’ frequent arguments that such games are apolitical.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/18957380/Screen_Shot_2019_08_09_at_3.44.18_PM.png)

Another game Cypheroftyr has found disturbing in its attempt to background politics without any real self-reflection is the popular adventure game Detroit Become Human , which displays pacifist Martin Luther King Jr. quotes alongside gameplay that allows players to choose extreme violence as an option. “You can take a more pacifistic approach, but you may not get the ending you want,” she explained.

She noted, too, that the military uses video games for training as part of what’s been dubbed the “ military-entertainment complex ,” with tactics involving shooter games that some ex-soldiers have referred to as “more like brainwashing than anything.” The US Army began exploring virtual training in 1999 and began developing its first tactics game a year later. The result, Full Spectrum Command , was a military-only version of 2003’s Full Spectrum Warrior . Since then, the military has used video games to teach soldiers everything from how to deal with combat scenarios to how to interact with Iraqi civilians .

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19099945/GettyImages_152915237.jpg)

The close connection between games and sanctioned real-world violence, i.e., war, is hard to deny with any plausibility. “When someone insists that these two parts of culture have absolutely nothing to do with each other,” Clark said, “it smacks of denial, and many game developers are asking themselves, ‘Do I want to be part of this landscape?’ even if they have zero belief that video games are causing violence.”

For all the gaming industry’s faults when it comes to frankly addressing gaming’s role in a violent culture, however, many people are quick to point out that critiques of in-game violence can also come from the video games themselves. In Batman: Arkham Asylum , for example, researchers Christina Fawcett and Steven Kohm recently found that the game “directly implicate[s] the player in violence enacted upon the bodies of criminals and patients alike.” Other games shift the focus away from the perpetrators to the victims — for example, This War of Mine is a survival game inspired by the Bosnian War that focuses not on soldiers but on civilians dealing with the costs of wartime violence.

But acknowledging that critiques of violent games are coming from within the gaming community doesn’t play well as part of the gun control debate. “It’s far too easy to scapegoat video games as low-hanging fruit instead of addressing the real issues,” Cypheroftyr said, “like the ease with which we can get weapons in this country, and why we don’t do more to punish the perpetrators [of gun violence].” She also cites the cultural tendency to excuse masculine aggression early on with a “b“boys will be boys” mentality — which can breed the kind of entitlement that leads to more violence later on.

All these factors combine to make the conversation around violent video games inherently political and part of a larger ongoing debate that ultimately centers on which media messages are the most responsible for fueling real-world violence.

The conversation surrounding violent games implicates violent gaming culture itself — which, in turn, implicates politicians who rail against games

Games journalist Carter told me he feels the gaming community needs to, in essence, reject the whole debate entirely because at this point in its life cycle, it’s disingenuous.

“We’ve been through enough shootings that you know the playbook, and it’s annoying that gamers and people in the industry will take this as a position that needs defending,” he told me. “It’s not a conversation worth having anymore solely on post-traumatic terms.”

Discussions about video game violence need to be held mainly within the games community, Carter said, and held “with people who are actually interested in figuring out a solution instead of politicians looking to pass off the blame for their ineptitude and greed.”

But some gamers told me they don’t trust the gaming community to frame the conversation with appropriate nuance. All of them cited Gamergate’ s violent male entitlement and the effect that its subsequent bleed into the larger alt-right movement’s misogyny and white supremacy have had on mainstream culture at large.

“The framing of that rhetoric that began in Gamergate as part of the ‘low’ culture of niche internet forums became part of the mainstream political discourse,” criminologist Phillips pointed out. “The expression of their misogyny and the notion of being pushed out of their white male-dominated space was a microcosm of what was to come. We’re talking about 8chan now, but [the growth of the alt-right] was fueled by gaming culture.” She points to Gamergate as an example of the complicated interplay between gaming culture, online communities full of toxic, violent rhetoric, and the rise of online extremism that’s increasingly moving offline.

Gaming sociologist Cross agreed. “At this moment, there is urgent need to shine a light on video game culture , the fan spaces that have been infiltrated by white supremacists looking to recruit that minority of gamers who rage against ‘political correctness,’” she told me.

“We treat video games as unreal, as unserious play, and that creates a shadow over gaming forums and fan communities that has allowed toxicity to take root. It’s also allowed neo-Nazis to operate mostly unseen. That is what needs to change.”

The resulting shadow over gaming has spread far and wide — and found violent echoes in the rhetoric of Trump himself . “Look at what the person in the very highest office of the US is cultivating,” Cypheroftyr said. “Toxic masculinity, this idea that men, especially white men, have been fed that they’re losing ‘their’ country.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19100007/GettyImages_1046898458.jpg)

“While video games do not influence us in a monkey-see-monkey-do manner, they do, like all media, shape how we see the world,” Cross argues. “Republicans, in broaching that possibility, open themselves up to the critique that their leader, who makes frequent use of both old media and social media, might also be influential in a toxic way.”

And this, ultimately, may be why the current debate around video games and violence feels particularly intense: The extremes of toxic gaming culture are fueling the attitudes of toxic alt-right culture , which in turn fuels the rhetoric of President Trump and many other right-wing politicians — the same rhetoric that many white supremacist mass shooters are using to justify their atrocities.

So when Trump rails against violence in video games, as he’s now done multiple times , he’s protesting a fictionalized version of the real-life violence that his own rhetoric seems to tacitly encourage. If we are to accept the argument that media violence as represented by games is capable of bringing about real-world violence, then surely no media influence is more powerful or full of dangerous potential than that wielded by the president of the United States.

In 2018, Vice’s gaming vertical Waypoint devoted a week to “ guns and games ”; in a moving piece outlining the intent of the project, editor Austin Walker observed that unlike real-world violence, “in big-budget action games, and especially games that give the player guns and plentiful ammunition, violence is cheap and endlessly repeatable.”

Yet now, barely a year later, mass shootings and other incidents of real-world violence have also begun to seem endlessly repeatable. Perhaps that is why, at last, the urgency of shifting our cultural focus from fixing violence in games to fixing violence in the real world feels like it is finally outstripping the incessant debate.

Will you help keep Vox free for all?

At Vox, we believe that clarity is power, and that power shouldn’t only be available to those who can afford to pay. That’s why we keep our work free. Millions rely on Vox’s clear, high-quality journalism to understand the forces shaping today’s world. Support our mission and help keep Vox free for all by making a financial contribution to Vox today.

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

We’re long overdue for an Asian lead on The Bachelor franchise

The story of kate middleton’s disappearance is haunted by meghan markle, the disappearance of kate middleton, explained, sign up for the newsletter today, explained, thanks for signing up.

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

The evidence that video game violence leads to real-world aggression

A 2018 meta-analysis found that there is a small increase in real-world physical aggression among adolescents and pre-teens who play violent video games. Led by Jay Hull, a social psychologist at Dartmouth College, the study team pooled data from 24 previous studies in an attempt to avoid some of the problems that have made the question of a connection between gaming and aggression controversial.

Many previous studies, according to a story in Scientific American, have been criticized by “a small but vocal cadre of researchers [who] have argued much of the work implicating video games has serious flaws in that, among other things, it measures the frequency of aggressive thoughts or language rather than physically aggressive behaviors like hitting or pushing, which have more real-world relevance.”

Hull and team limited their analysis to studies that “measured the relationship between violent video game use and overt physical aggression,” according to the Scientific American article .

The Dartmouth analysis drew on 24 studies involving more than 17,000 participants and found that “playing violent video games is associated with increases in physical aggression over time in children and teens,” according to a Dartmouth press release describing the study , which was published Oct. 1, 2018, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences .

The studies the Dartmouth team analyzed “tracked physical aggression among users of violent video games for periods ranging from three months to four years. Examples of physical aggression included incidents such as hitting someone or being sent to the school principal’s office for fighting, and were based on reports from children, parents, teachers, and peers,” according to the press release.

The study was almost immediately called in to question. In an editorial in Psychology Today , a pair of professors claim the results of the meta-analysis are not statistically significant. Hull and team wrote in the PNAS paper that, while small, the results are indeed significant. The Psychology Today editorial makes an appeal to a 2017 statement by the American Psychological Association’s media psychology and technology division “cautioning policy makers and news media to stop linking violent games to serious real-world aggression as the data is just not there to support such beliefs.”

It should be noted, however, that the 2017 statement questions the connection between “serious” aggression while the APA Resolution of 2015 , based on a review of its 2005 resolution by its own experts, found that “the link between violent video game exposure and aggressive behavior is one of the most studied and best established. Since the earlier meta-analyses, this link continues to be a reliable finding and shows good multi-method consistency across various representations of both violent video game exposure and aggressive behavior.”

While the effect sizes are small, they’ve been similar across many studies, according to the APA resolution. The problem has been the interpretation of aggression, with some writers claiming an unfounded connection between homicides, mass shootings, and other extremes of violence. The violence the APA resolution documents is more mundane and involves the kind of bullying that, while often having dire long-term consequences, is less immediately dangerous: “insults, threats, hitting, pushing, hair pulling, biting and other forms of verbal and physical aggression.”

Minor and micro-aggressions, though, do have significant health risks, especially for mental health. People of color, LGBTQ people , and women everywhere experience higher levels of depression and anger, as well as stress-related disorders, including heart disease, asthma, obesity, accelerated aging, and premature death. The costs of even minor aggression are laid at the feet of the individuals who suffer, their friends and families, and society at large as the cost of healthcare skyrockets.

Finally, it should be noted that studies looking for a connection between game violence and physical aggression are not looking at the wider context of the way we enculturate children, especially boys. As WSU’s Stacey Hust and Kathleen Rodgers have shown, you don’t have to prove a causative effect to know that immersing kids in games filled with violence and sexist tropes leads to undesirable consequences, particularly the perpetuation of interpersonal violence in intimate relationships.

No wonder, then, that when feminist media critic Anita Saarkesian launched her YouTube series, “ Tropes vs. Women in Video Games ,” she was the target of vitriol and violence. Years later she’d joke about “her first bomb threat,” but that was only after her life had been upended by the boys club that didn’t like “this woman” showing them the “grim evidence of industry-wide sexism.”

Read more about WSU research and study on video games in “ What’s missing in video games .”

- Free AI Essay Writer

- AI Outline Generator

- AI Paragraph Generator

- Paragraph Expander

- Essay Expander

- Literature Review Generator

- Research Paper Generator

- Thesis Generator

- Paraphrasing tool

- AI Rewording Tool

- AI Sentence Rewriter

- AI Rephraser

- AI Paragraph Rewriter

- Summarizing Tool

- AI Content Shortener

- Plagiarism Checker

- AI Detector

- AI Essay Checker

- Citation Generator

- Reference Finder

- Book Citation Generator

- Legal Citation Generator

- Journal Citation Generator

- Reference Citation Generator

- Scientific Citation Generator

- Source Citation Generator

- Website Citation Generator

- URL Citation Generator

- AI Writing Guides

- AI Detection Guides

- Citation Guides

- Grammar Guides

- Paraphrasing Guides

- Plagiarism Guides

- Summary Writing Guides

- STEM Guides

- Humanities Guides

- Language Learning Guides

- Coding Guides

- Top Lists and Recommendations

- AI Detectors

- AI Writing Services

- Coding Homework Help

- Citation Generators

- Editing Websites

- Essay Writing Websites

- Language Learning Websites

- Math Solvers

- Paraphrasers

- Plagiarism Checkers

- Reference Finders

- Spell Checkers

- Summarizers

- Tutoring Websites

Most Popular

10 days ago

Cognition’s New AI Tool Devin Is Set To Revolutionize Coding Industry

Heated discussions erupt on reddit over chatgpt’s entry in scholarly publication, do you use quotation marks when paraphrasing, typely review, how to rewrite the sentence in active voice, why teens should not be allowed to play violent video games essay sample, example.

Times when children would spend their entire free time playing with peers in the streets have mostly gone. Modern children and teenagers prefer calmer forms of entertainment, such as watching television, or in a large degree, playing video games. Although video games can contribute to a child’s development, many of them, unfortunately, are extremely violent. Moreover, games propagating murder and violence, such as Mortal Kombat, Outlast, Grand Theft Auto, and so on, are popular and are being advertised everywhere, making teenagers willing to play them; the fact that they are marked by the ESRB (Entertainment Software Rating Board) does not help much. However, considering the nature of such games, they should not be allowed for teens to play.

For the human brain, there is no big difference between a real-life situation, and an imaginary one; this is why we get upset even if we think about something unpleasant. For children and teens, who usually have a rich imagination, everything is even more intense. Virtual experiences for them may feel as real as daily life; this happens due to advanced technologies, making computer graphics look extremely close to reality, and also because players take a first-person role in the killing process (often with the view “from a character’s eyes”). If they would passively watch a violent game, it would make less harm than acting as a character who makes progress through a plot by murdering people and destroying what is in the character’s path. This situation is negative, as a child’s or teen’s brain forms new connections every day—they actually learn and memorize what is going on in their favorite games ( HuffingtonPost ).

Moreover, violent games directly reward violent behavior; many modern games do not simply make make players kill virtual reality characters of other players online, but also grant them with scores (experience) or points for successful acts of violence. These points are usually spent on making a player’s character even more efficient in killing, unlocking new cruel ways of murdering, and so on. Sometimes, players will be even praised directly, verbally; for example, in many online shooters, after conducting a killing, players hear phrases like “Nice shot!” encouraging further violence. This is much worse than watching TV, as TV programs do not offer a reward directly tied to the viewer’s behavior, and do not praise viewers for doing something anti-social ( ITHP ).

According the American Psychological Association, violent video games increase children’s aggression. Dr. Phil McGraw explains, “The number one negative effect is they tend to inappropriately resolve anxiety by externalizing it. So when kids have anxiety, which they do, instead of soothing themselves, calming themselves, talking about it, expressing it to someone, or even expressing it emotionally by crying, they tend to externalize it. They can attack something, they can kick a wall, they can be mean to a dog or a pet.” Additionally, there’s an increased frequency of violent responses from children who play these kinds of video games ( Roanna Cooper ).

Unfortunately, many modern games incorporate violence. Having youth play these video games are dangerous, as teenagers and children usually take a first person role in the killing process, and even get rewarded or praised for doing so. According to numerous studies, this leads to an increase of aggression in them.

John, Laura St. “8 Ways Violent Games Are Bad for Your Kids.” The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, n.d. Web. 09 Apr. 2015.

“The Effects of Violent Video Games. Do They Affect Our Behavior?” ITHP. N.p., n.d. Web. 09 Apr. 2015.

“Children and Violent Video Games.” Dr. Phil.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 09 Apr. 2015.

Follow us on Reddit for more insights and updates.

Comments (0)

Welcome to A*Help comments!

We’re all about debate and discussion at A*Help.

We value the diverse opinions of users, so you may find points of view that you don’t agree with. And that’s cool. However, there are certain things we’re not OK with: attempts to manipulate our data in any way, for example, or the posting of discriminative, offensive, hateful, or disparaging material.

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

More from Best Persuasive Essay Examples

May 28 2023

How does outdoor exercises impact our health and well-being? Essay Sample, Example

Should Screen Time Be Limited? Essay Sample, Example

Why Video Games are Good for the Brain. Essay Sample, Example

Related writing guides, writing a persuasive essay.

Remember Me

Is English your native language ? Yes No

What is your profession ? Student Teacher Writer Other

Forgotten Password?

Username or Email

Violent video games: content, attitudes, and norms

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 16 October 2023

- Volume 25 , article number 52 , ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Alexander Andersson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4911-3853 1 &

- Per-Erik Milam 1

3218 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Violent video games (VVGs) are a source of serious and continuing controversy. They are not unique in this respect, though. Other entertainment products have been criticized on moral grounds, from pornography to heavy metal, horror films, and Harry Potter books. Some of these controversies have fizzled out over time and have come to be viewed as cases of moral panic. Others, including moral objections to VVGs, have persisted. The aim of this paper is to determine which, if any, of the concerns raised about VVGs are legitimate. We argue that common moral objections to VVGs are unsuccessful, but that a plausible critique can be developed that captures the insights of these objections while avoiding their pitfalls. Our view suggests that the moral badness of a game depends on how well its internal logic expresses or encourages the players’ objectionable attitudes. This allows us to recognize that some games are morally worse than others—and that it can be morally wrong to design and play some VVGs—but that the moral badness of these games is not necessarily dependent on how violent they are.

Similar content being viewed by others

Psychological Reactance to Anti-Piracy Messages explained by Gender and Attitudes

Kate Whitman, Zahra Murad & Joe Cox

Speaking to the Other: Digital Intimate Publics and Gamergate

Virtual experience, real consequences: the potential negative emotional consequences of virtual reality gameplay

Raymond Lavoie, Kelley Main, … Danielle King

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Violent video games (VVGs) are a source of serious and continuing controversy. They are not unique in this respect, though. Other entertainment products have been criticized on moral grounds, from pornography to heavy metal, horror films, and Harry Potter books. Some of these controversies have fizzled out over time and have come to be viewed as cases of moral panic. Footnote 1 Others, including moral objections to VVGs, have persisted. The aim of this paper is to determine which, if any, of the concerns raised about VVGs are legitimate.

Moral objections to VVGs have three main components, which can be understood as answers to the following three questions:

Moral Question: Why are VVGs morally bad or wrong?

Comparison Question: Why are they worse than other forms of violent entertainment?

Regulation Question: What should be done about them?

For example, one might argue that VVGs desensitize players to violence thereby making them more likely to act violently themselves, that VVGs do this more effectively than violent films or books, and that VVGs should therefore be prohibited or strongly regulated.

In this paper, we evaluate the most common answers to the moral and comparison questions, but set aside the regulation question. Not only does regulation raise a number of other ethical considerations—including free speech, paternalism, and policy design and enforcement—it also requires that we first understand the comparative badness of VVGs.

The paper is structured as follows. Section “ Background and preliminaries ” gives a brief overview of the controversies surrounding VVGs and explains how we will structure and focus our evaluation. Section “ The causation argument ” considers the claim that it is wrong to design and play VVGs in virtue of their bad consequences and concludes that the empirical evidence that playing VVGs causes bad outcomes is inconclusive, and that even if we grant that they have bad effects, VVGs are not distinctively bad in this respect. Section “ The violence argument ” considers the claim that VVGs are bad in virtue of features like realism that are independent of their consequences, but we conclude that existing accounts of these features fail to adequately explain why some VVGs should be considered morally objectionable. Having rejected these accounts of the comparative badness of VVGs, Sect. “ The internal logic of violent video games ” offers an alternative explanation.

Background and preliminaries

There is a history of blaming VVGs for violent acts such as school shootings, mass shootings, and murder in the United States. Footnote 2 Games such as Mortal Kombat, Doom , and Manhunt have all caused controversy in the past. They depict gory, brutal, and gratuitous violence as entertainment. For the uninitiated it may be inexplicable why anyone would enjoy what is happening on screen. Hence, the popular sentiment seems to be that there must be something morally bad about these games.

Since VVGs have been picked out as especially bad, we want to investigate whether it is justified to single them out for criticism. We will argue that most, but not all, common criticisms of VVGs are unjustified. Moreover, any justified criticism will also apply to other forms of entertainment. Thus, for any particular VVG, we must conclude either that it is morally permissible to design and play it or that it is morally wrong to create and consume other relevantly similar entertainment products. Which conclusion is warranted will depend on the details of the case.

However, there are multiple ongoing debates about the comparative badness of VVGs, so, before making any substantive claims, let us first explain how we will structure and focus our investigation.

Targets . While concerns about VVGs appear to be about the video games themselves, games are not natural evils like an earthquake or a volcanic eruption. They are designed and played—not to mentioned commissioned and distributed—by moral agents. We therefore focus on the two most plausible targets of these criticisms: players and developers. Insofar as a game is criticized on moral grounds, we take this to be a criticism either of those who created its content or those who created the particular instances of violence by playing the game. Some may object that critics should direct their objections and blame at the companies that commission the games and the governments that fail to regulate them properly. Maybe so. But such criticisms presuppose that there is something objectionable about the games themselves or about playing them.

Topics . Even limiting our attention to developers and players leaves many issues to consider. Multiplayer online gaming has given rise to concerns about toxic environments and interactions, which may be influenced by the violent content of many of these games. This is a serious problem and one where reforms are possible and can make a real difference to the well-being and experience of gamers, but we will not address it here. Nor will we consider the moral status of violent assault on another player’s avatar—e.g. robbing them for items, killing them out of spite, or ‘griefing’ them. These kinds of behaviors also deserve attention, but they introduce potentially confounding variables into an analysis because they involve moral agents who can be harmed through the treatment of their avatars. We therefore limit our focus to single-player VVGs Footnote 3 —i.e., video games that include violence or violent themes—including those singled out in debates about the ethics of VVGs, like Doom, Grand Theft Auto V, Last of Us II.

It should also be noted that while we use the term “VVG” to denote a specific category of games, what we are essentially interested in is moral agency in games in general. However, since most discussions relating to this topic focuses on violence and VVGs, that is where our main focus will be as well. Having restricted our task in these ways, let us now consider why it might be morally wrong to develop or play VVGs.

The causation argument