Why You Should Learn to Swim: It Could Save Your Life

Thousands in the U.S. drown accidentally each year.

Years before he became a U.S. Olympic swimmer, Cullen Jones almost drowned in front of his parents.

Young Cullen loved the water. He happily spent hours in the bathtub, “until I was a prune,” he recalls. At age 5, his parents took him to a water park in Pennsylvania. His father slid down a water slide in an inner tube, followed by a gleeful Cullen. His joy quickly turned to terror. “I flipped upside down,” Jones, now 33, says. “Underwater, I held onto the inner tube, trying to pull myself up, but I didn’t have the strength.” Cullen lost consciousness; a lifeguard rescued and helped resuscitate him .

The terrifying episode prompted Jones’ parents to take him to swimming lessons. Jones – who won a gold medal as part of a U.S. men’s freestyle relay team in the 2008 London Olympic Games – recounts his near-drowning as part of his efforts to encourage kids, adolescents, teenagers and adults to learn to swim on behalf of the USA Swimming Foundation's “Make a Splash” program. He and other proponents of swimming and water safety point out that every year, about 3,500 people in the U.S. accidentally drown, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Swimming is “not only a recreational activity – it’s a skill that saves lives,” says Lindsay Mondick, senior manager-aquatics for the YMCA. Swimming programs not only teach people how to swim, but they also provide other safety training, such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation lessons, demonstrations of how to use safety equipment, such as flotation devices, and tips on safer places to swim.

[See: 7 Exercises You Can Do Now to Save Your Knees Later .]

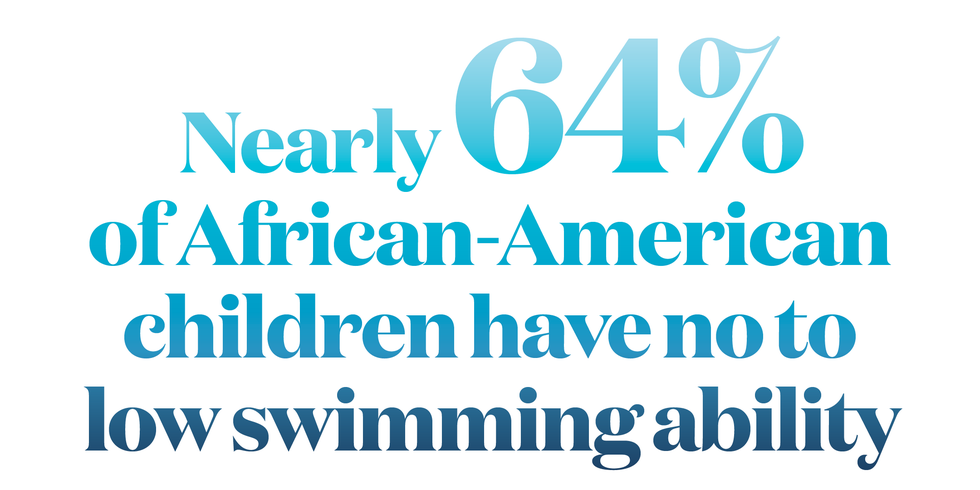

Outreach efforts by the USA Swimming Foundation (which works with hundreds of local pools), the YMCA and hundreds of local recreation programs are making a difference, says Debbie Hesse , executive director of USA Swimming Foundation. The foundation recently released a new study by the University of Memphis and the University of Nevada-Las Vegas measuring the swimming ability of kids ages 4 to 18 and parents and other caregivers in the U.S. Within this group, the study found that 64 percent of African-Americans, 45 percent of Hispanics and 40 percent of Caucasians have little or no swimming ability, which puts them at risk for drowning. Those numbers may not sound great, but they’re an improvement of 5 to 10 percent (depending on the group) over a 2010 survey released by the foundation. That survey found that 70 percent of African-Americans had little or no swimming ability.

A 2014 study by the CDC found that the rate of drowning in swimming pools for black kids and teens between ages 5 and 19 is more than five times that of white children. This lack of swimming ability has led to some high-profile tragedies: In August 2010, for example, a black teenager wading along the Red River shoreline near Shreveport, Louisiana, slipped off a ledge into deeper water. The teen didn’t know how to swim and yelled for help. Five siblings and cousins rushed into the water to save him – but none of them could swim, either. All six drowned.

Pre-civil rights era Jim Crow policies account for why relatively few African-Americans have learned how to swim, says Jeff Wiltse , a history professor at the University of Montana who wrote “The Black-White Swimming Disparity in America: A Deadly Legacy of Swimming Pool Discrimination,” published in 2014 in the Journal of Sport and Social Issues. He also wrote the book “Contested Waters: A Social History of Swimming Pools in America.”

“The comparatively low swimming rates among black Americans today is, in large part, a legacy of past discrimination. Swimming became popularized among white Americans in the 1920s and 1930s at municipal swimming pools and in the 1950s and 1960s at suburban club pools,” Wiltse says. “Black Americans were largely denied access to these pools and the swim lessons that occurred at them. As a result, swimming never became integral to black Americans’ recreation and sports culture and was not passed down from generation to generation as commonly occurred with whites. In many cases, black parents passed along a fear of water to their children rather than the practice of swimming. In this way, the swimming disparity created by past discrimination persists to the present.”

[See: The 10 Most Underrated Exercises, According to Top Trainers .]

Jones, one of the most prominent African-American swimmers in U.S. history, hopes he and other black swimmers can serve as role models for black youths. Jones wants blacks and everyone else to not only learn swimming for safety reasons, but to improve their health. Swimming is great exercise that's easy on the joints, so it’s excellent for people with arthritis . It doesn’t take a toll on your feet or legs the way high-impact exercise can. Swimming can also help ward off diabetes , obesity and heart disease. “The ball is rolling, but there’s a lot more work to be done,” Jones says.

If you want to learn how to swim and get water safety training, or want your child to take swimming lessons, experts suggest these strategies:

Consider your options. Between programs offered by the USA Swimming Foundation, the YMCA, local parks and recreation centers and private swim schools, you should be able to find a regimen that suits your child or you in your area virtually everywhere in the country. At the foundation’s website , you can find more than 1,000 lesson providers.

Look for affordable lessons. This year, the YMCA will provide 27,000 scholarships for swimming lessons in underserved communities , Mondick says. The USA Swimming Foundation will provide $450,000 in grants this year to provide free or reduced-cost swimming lessons to children whose families otherwise wouldn't be able to afford them. And the Los Angeles County Department of Parks and Recreation has 31 swimming pools and another 30 splash pads (areas for water play that have no standing water, but could have ground nozzles) and small water parks, says Joe Goss, chief of the department’s aquatics program. In partnership with the American Red Cross, the department offers free swimming lessons in disadvantaged areas.

Keeping Your Kids Healthy at Summer Camp

Lisa Esposito June 19, 2014

Don’t procrastinate. Many people have a “this will never happen to me” attitude about drowning, says Jim O’Connor, aquatics safety coordinator for Miami-Dade County’s Department of Parks, Recreation and Open Spaces. “It only takes 20 to 60 seconds for someone to be totally submerged in water,” he says. “It can happen quickly in a backyard pool with an unsupervised child."

The danger can be deceptive because “drowning doesn’t look like drowning,” says Lauren Bordages , director of Stop Drowning Now, an organization based in Tustin, California, that's dedicated to saving lives through drowning prevention and water safety education. “Drowning isn’t a splashy dramatic scene from television,” she says. “Drowning is silent.”

Don’t let age stop you. Some swimming programs offer training to children as young as 3 months. At that age, it’s about getting kids acclimated to water. Conversely, no one is ever too old to learn how to swim, Jones says. His mom, who’s 66, is planning on taking swim lessons this year. “You can learn to swim at any age,” he says.

[See: 8 Healthy West Coast Habits East Coasters Should Adopt .]

Have fun. “Swimming is one of the best ways to cool off in the summer heat and a fun way to stay active,” says Keith Anderson , director of the District of Columbia Department of Parks and Recreation. “Take it from me; I swam as a youth, and it was one of my favorite sporting activities.”

7 Ways to Boost Poolside Confidence Without Changing Your Body

Tags: sports , water , water safety , death

Most Popular

health disclaimer »

Disclaimer and a note about your health », you may also like, the best supplements to build muscle.

David Levine and Elaine K. Howley April 11, 2024

Exercises for Osteoarthritis

Vanessa Caceres March 29, 2024

When to Stop Exercising Immediately

Elaine K. Howley and Anna Medaris Miller March 25, 2024

Best Workouts for Women Over 50

Cedric X. Bryant March 14, 2024

Yoga for Knee Pain

Jake Panasevich Feb. 29, 2024

You Should Use These 9 Gym Machines

Ruben Castaneda , K. Aleisha Fetters and Payton Sy Feb. 23, 2024

Exercise: How Much Do You Need?

Cedric X. Bryant Feb. 15, 2024

How to Prevent Pickleball Injuries

Cedric X. Bryant Jan. 25, 2024

Are Energy Drinks Bad For You?

Elaine K. Howley and Anna Medaris Miller Jan. 19, 2024

Mind-Blowing Benefits of Exercise

Vanessa Caceres and Stacey Colino Jan. 10, 2024

Metropolitan YMCA of the Oranges

The Importance of Swim Lessons

By: Mollie Shauger | Thursday, June 20, 2019 | Aquatics

Child learning how to swim

Swim lessons are a great way to prepare young swimmers to enjoy the water in a much safer way. Here at the YMCA, we offer a number of learn-to-swim classes for swimmers of all ages. Beyond enjoyment, swim lessons offer new swimmers a number of benefits that can last a lifetime.

Improve Safety – For Everyone

Sadly, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention reports that more than 3,400 people drown in the United States each year. Those that know how to swim are far more equipped to rescue someone that is struggling to swim. Furthermore, it’s a valuable skill to have for those who work with, or supervise, young children, who are more susceptible to suffering an injury while swimming.

Additionally, teaching children to swim at a young age helps prepare them to be safer around bodies of water. Swim lessons help adults and children become more comfortable in the water, and teaches them to float and safely operate in the water. This also empowers them to attend pool parties and enjoy social time with their friends in and around the water.

Healthy Benefits for Young Children

Children can take water safety courses or parent-child swimming lessons as early as 2-months old. Multiple studies have found many physical and neurological benefits of teaching children to swim in their toddler years. A long-term study performed by Griffith University found that 3-5 year old’s who learned to swim early had better verbal, math, and literacy skills when compared to children their same age that didn’t know how to swim. Furthermore, teaching young children to swim improves their self-control, boosts their self-esteem and gives them more self-confidence to handle new situations. Swimming also helps children develop healthy muscles, and improves their cardiovascular health and performance.

Incredible Health Benefits

Swimming is one of the best exercises a person can do, and it offers a list of incredible health benefits. First, swimming is a low-impact sport, which makes it great for any person of any age to practice. Seniors often enjoy swimming as a healthy cardiovascular exercise that won’t upset their joints. Unlike running or lifting weights, the low-impact of swimming empowers people to enjoy the sport their entire lives. Swimming is also an exercise that engages a lot of muscle groups, which makes it an incredible full-body workout. Swimming has been proven time and again to be one of the best calorie-burning exercises, and can aide in weight-loss, muscle growth, and promotes better overall cardiovascular health.

Excellent Competition

Swimming is a fun sport open for children of all ages to compete. Competitive swimming gives people a chance to train with a team and make new friends in a healthy space. Competitive swimming also offers students a chance to earn a scholarship and compete in college. This can help parents save money on expensive tuition costs, and gives their child a huge head-start on earning new friends while away at school.

Relaxing Fun

Most people that know how to swim get real enjoyment and relaxation from spending leisure time in the water. Being able to swim allows people to escape a hot summer day by going to the pool, or a natural body of water. The skill itself opens up an entirely natural world of lakes, rivers and oceans to explore and enjoy as a swimmer. You can hop in the boat with some friends to go water skiing, or enjoy snorkeling in the ocean and observing the countless wonders of the sea. Swimming doesn’t have to be relegated to a pool, and it’s a skill that empowers people to explore. So, if you don’t know how to swim, or you want to teach your family to swim, then contact the YMCA for more information about our many learn-to-swim programs .

A True Lifelong Skill

Swimming is a life-long skill that swimmers can practice year-round. According to the CDC, swimming can help with chronic diseases and mental health. Water-based exercising like swimming improves the use of joints affected by arthritis, and can help seniors exercise in a healthy environment long after retirement.

Learn to Swim at the YMCA

The Metro YMCA in northern NJ provides water safety classes for the whole family, so that each member of your family is confident around bodies of water. We also offer swim lessons for children with moderate-to-severe neurological, physical, or social challenges.

Call us today to learn more about our swimming lessons. Because the Y is for all, we offer financial assistance for qualifying individuals and families who want to participate in our programs.

7 comments on "The Importance of Swimming Lessons"

Leave a Comment

Related blog posts, metro ymca of the oranges joins the five days of action, new milford ymca program center offering swim lessons, west essex ymca offers free participation in piranhas swim team, metro ymca of the oranges named top workplace.

YMCA Accreditations

‘Learning To Swim At 24 Taught Me An Important Life Lesson’

Assistant editor Naydeline Mejia shares how she came to peace with the water.

It was the summer of 2018. My sister, cousin, and I were aboard a motorboat with seven other wide-eyed tourists hoping to catch a glimpse of the sunken statues off the coast of Isla Mujeres, Mexico. As we pulled away from the beach, I watched the celeste-hued water transform into a midnight blue and realized I could no longer rely on my fragile safety net—the knowledge that I’d be able to see my feet on the ocean floor. This was deep sea.

After about 15 minutes, our captain stopped the vessel and began to distribute the essentials alongside his assistant: life jackets, flippers, and goggles.

“Anyone who wants to get in and see the statues, now’s your chance,” he announced in Spanish, our shared mother tongue.

While I’m aware of the human body’s natural buoyancy in saltwater, I’m also conscious that the ocean will not hesitate to swallow one whole at the first sign of fear. In other words, I wasn’t about to risk it.

I’ve never been a particularly strong swimmer.

While I'd participated in an entire year of swimming lessons in the sixth grade—a rare opportunity for a low-income Black girl attending a West Bronx public school—sometime between the start of puberty and the beginning of adulthood, I had become increasingly aware of my own mortality. For me, this awareness largely manifested in a fear of drowning. When it comes to water-based activities, I prefer to stand comfortably in the shallow end.

And so, one by one, my boat mates made their way into the water. But I stayed onboard. As my family members and the other tourists followed the captain to see the life-sized sculptures which sat 30 feet under the surface, I began to viciously sob—failing miserably to hide my shame from the deckhand watching me as I swallowed my own salty tears.

I’ve always felt a deep connection to bodies of water . Whenever I feel overwhelmed, I search for a waterfront—a rarity in my concrete jungle home of New York City. My affinity also makes sense, since being in or near water has been linked to a reduction in stress, alleviated anxiety, and a boost in overall mood, according to licensed therapist Shontel Cargill, LMFT.

Yet, the visceral pain I felt that day from not being able to jump freely into the water is not something even I truly grasp. It felt like I’d tapped into a deep source within me—an ancestral struggle, almost. It was like I could hear the synchronous wails produced by my collective bloodline, begging for freedom from the forces that kept them shackled to the island of La Española—fearing yet worshiping the water gods.

It’s a common racist trope that Black people can’t swim.

But it’s hard to ignore this one’s startling reality. Nearly 64 percent of African-American children have no to low swimming ability, compared to 45 percent of Hispanic children and 40 percent of Caucasian children, according to USA Swimming . Moreover, Black children drown at rates three times higher than white children, per the CDC .

And it's not just children who are affected. Black people, in general, drown at higher rates than any other demographic, says Paulana Lamonier, the founder and CEO of Black People Will Swim , a mission-based program empowering Black and brown people to be more confident in the water. I first learned about Paulana and her mission after reading a feature on her on CNBC , and knew that when I decided to begin my swim journey, it would be with her.

“The reason why it’s important for us to teach people these life-saving skills is simply that: because it is a life-saving skill,” she tells me. “We’re really giving people that chance to dream again; the chance and opportunity for freedom. When you’re on vacation, you no longer have to sit poolside—you don’t have to be scared to jump.”

Twenty minutes past noon on Saturday, May 20, 2023, I went to my first swim class.

I arrived at CUNY York College’s Health and Physical Education Building where classes for Black People Will Swim’s spring 2023 program were being held. By the time I reached the 25-meter swimming pool, class was already in session.

Paulana, a warm yet commandeering figure, was teaching the class, and invited me to join. As I slowly and awkwardly slid my way into the pool's shallow end, I took in the expressions around me. There was a variety of ages in our adult-beginner course, which was made up of all Black women. Young 20-somethings, like myself, women in their 30s and 40s, and even a few Aunties—elders, often mature women over the age of 50.

Our first lesson started with a breath. We were to learn how to breathe underwater.

One by one, Paulana went around asking each of us to hop down into a squat until our fingertips touched the pool floor. Once there, rather than sucking in air through our nostrils, we were to expel that air by blowing bubbles—holding in the remaining oxygen in our mouths. When my hands touched the bottom of that pool and I was surrounded by blue I felt—if only for a second—at home. If only I could breathe underwater , I thought, I would never leave .

“The water was like my getaway,” says Maritza McClendon , a 2004 Olympic silver medalist and the first Black female to make the U.S. Olympic swim team. “Every time I get in the water, I’m in my happy place—I’m in my element.”

McClendon—who, after being diagnosed with scoliosis, began swimming at the age of six per her doctor’s recommendation—has always found solace in the water, even when the pressures of competitive swimming weighed her down.

"When I got in the pool, it was like I went into an oasis and forgot about everything—it was just me and the water.”

As I re-emerged from the pool after that first drill, I suddenly became aware of my senses. The silence from being submerged disappeared, and I was met with the noises around me.

To my right, one of my classmates—an older woman perhaps in her mid-60s to early 70s—was holding onto the edge, quietly blowing bubbles to herself as the rest of the class moved onto the next lesson.

I pondered what experience may have caused her to develop this palpable fear, and ultimately lead her here today. I also wanted to grab her hand and walk her to the middle of the pool, so we could float together like two otters, holding on tight to ensure the other wouldn't float too far away, and she could share some of the joy I felt.

The truth is, part of the reason why many Black and brown Americans don’t know how to swim today is a result of racial and class discrimination.

“There were two times when swimming surged in popularity—at public swimming pools during the 1920s and 1930s and at suburban swim clubs during the 1950s and 1960s. In both cases, large numbers of white Americans had easy access to these pools, whereas racial discrimination severely restricted Black Americans’ access,” wrote Jeff Wiltse, a historian and author of Contested Waters: A Social History of Swimming Pools in America , in a 2014 paper published in the Journal of Sport and Social Issues .

The systemic impairing of Black Americans’ ability to swim—thanks to poorly maintained and unequal swimming pools, private clubs that barred Black members, and public pool closures in the wake of desegregation—meant that swimming became a “self-perpetuating recreational and sports culture” for white Americans, says Wiltse. Black communities struggled to literally and metaphorically get a foot in.

“[Swimming] is a predominantly white sport,” says McClendon. (FYI: Of the 331,228 USA Swimming members, less than 5 percent are Black or African American, according to the 2021 Membership Demographics Report .)

“Growing up, I was definitely one of the few at every single swim meet, and even on my swim team,” McClendon recounts. “As early as nine years old, I remember finishing a race in which I got first, and walking past a parent who said, ‘You should go back and do track or basketball. What are you doing here?’ Sort of questioning why I was in the sport. If anyone else would’ve won the race, they would’ve been congratulating them.”

While most of McClendon’s career spans the 1990s and early 2000s, she says instances like this still happen today.

I missed the next three weeks of classes, so by the time I walked into my second swim session, I felt energized yet daunted.

As soon as I got in the pool, I asked my classmates about their reasons for joining the Black People Will Swim program.

One woman shared that she wanted to learn how to swim because she’s the only one in her family that couldn't and she had a seven-month-old son: “If he’s drowning, I want to be able to save him,” she tells me.

The second woman I spoke to said almost drowning twice pushed her to want to learn.

Unsurprisingly, most of these reasons pertain to survival. Swimming , at the end of the day, is a skill needed to live; it’s an ability and privilege that so many take for granted.

At the start of that second class, I was anxious. I had missed so much during my time away, and we were at the point of the program where everyone was expected to navigate the 14-foot end of the pool. Our first lesson of the day: butterfly backstrokes. I tried my best to prolong my turn by generously offering that my other classmates go ahead of me, but eventually I had to go.

As I positioned my feet on the wall, held onto the edge of the pool, and laid my head back, I silently repeated to myself, You got this! You are a child of the water. You will not drown. “Ready?” asked the instructor who was teaching my class. With one deep breath, off I went.

As soon as I started kicking my feet and pushing the water forward with my arms, I was making headway. It felt so natural, like muscle memory. Perhaps those middle school swim lessons did teach me something. After about five strokes, I was ordered to stop so the next person could demonstrate if they were ready to move on to the next step.

Swimming is easy enough when you know you can safely land on your feet the moment you start to panic, but once the depth of the pool is above my own height (at 5'4"), I no longer feel at ease. So you can imagine my nervousness when the instructor said we were about to backstroke the entire 25-meter pool.

As I prepared for that feat on the wall, I recounted the memory of that fateful summer of 2018, when I was too afraid to jump off the boat without a lifejacket. Then there was another memory: 11-year-old Naydeline, unafraid to jump into the deep end. Instead, exhilarated by it.

“Ready?” asked the instructor.

Off I went, rapidly backstroking across that 25-meter pool. I was making headway, but as I reached the 12-meter mark, I stopped. I was beginning to swallow water, and the chlorine-tinged liquid filling my throat made me panic. I was no longer swimming, but sinking. I quickly grabbed the nearest lane rope to stabilize myself.

“What happened?” asked my instructor. “You were doing so well.”

“I panicked,” was all I could say. The intrusive thoughts had started to pour in as soon as I sensed the depth of the pool change from six feet to eight feet to 10 feet: You’re drowning, you’re drowning, you’re drowning , and my anxiety took over.

It took a few seconds to catch my breath, but then I turned to face the deep end of the pool. I realized there was no getting out of this—I had to keep going. With my instructor situated behind me to catch me if I began to drown, I shut my eyes and inhaled for three counts, exhaled for three counts, again and again. Ready?

I was off once more. I didn’t stop until I hit the end of the pool.

A month after the end of the swim program, I headed out on a trip to the island of Aruba.

The schedule was filled with walking tours, parasailing, and an exploration of one of the island’s many natural pools.

The author parasailing off a boat at Palm Beach, Aruba.

On the second to last day, we kayaked across a small portion of the Caribbean Sea to go snorkeling. There would be coral reefs, parrotfish, and lobsters. I opted out.

I wasn’t confident that I wouldn’t start to panic and drown. So, while the rest of my tour group and the instructor went ahead, I stayed seated on the dock. As I looked out at the expansive sea around me, noticing how the colors transitioned from celeste to navy, I breathed in deeply: 1, 2, 3, 4, 1, 2, 3, 4 . I was trying my best not to cry.

Our reserved, yet warm tour guide had also stayed behind. He claimed he was tired of beautiful beaches and ocean views—they didn’t impress him, he said. After noticing that I had been sitting alone on the dock for what felt like half an hour, he came to sit next to me. I told him about my deep affinity for the sea, but also how much it terrified me.

“The trick to swimming,” he said, “is letting go of fear. […] The water will do most of the work for you. It’ll hold you up, but only if you let it. You must remain calm, and trust yourself.”

Perhaps that is the missing puzzle piece: trust. Trust in the water, but most importantly, trust in myself. Trust that I could keep myself alive, and the water would help me—if I let it.

Naydeline Mejia is an assistant editor at Women’s Health , where she covers sex, relationships, and lifestyle for WomensHealthMag.com and the print magazine. She is a proud graduate of Baruch College and has more than two years of experience writing and editing lifestyle content. When she’s not writing, you can find her thrift-shopping, binge-watching whatever reality dating show is trending at the moment, and spending countless hours scrolling through Pinterest.

All The Pregnant Celebrities With 2024 Due Dates

BBC Gives Statement on Kate Middleton Complaints

Taylor Swift Talks Her Personal Heartbreak

The Rebirth Of Megan Thee Stallion

Here's What Your Numerology Number Really Means

Why Paris Hilton Never Shows Her Daughter on Insta

Meghan Markle Visits Children's Hospital

Tay and Trav Took a Secret Trip to Nashville

Take 15% Off At Saatva—This Week Only

This Shark Vacuum Is On Sale For

What April's New Moon/Solar Eclipse Means For You

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience and security.

Please enable JavaScript for a better experience.

April 20th is Healthy Kids Day

Free community event with activities for kids and the entire family

The Importance of Swim Lessons for Kids and Adults

June 29, 2023 Aquatics

Are you ready to make a splash and prioritize water safety for yourself and your loved ones? Join us as we dive into the world of swim lessons and explore why they are essential for both kids and adults. Whether you're a beginner or looking to refine your skills, swim lessons offer invaluable benefits that go beyond just learning how to swim.

Building Confidence and Safety

Swim lessons provide a foundation of confidence and safety in and around the water. For children, learning to swim at an early age instills a sense of self-assurance , helping them feel comfortable and secure in aquatic environments. Adults, too, can benefit from swim lessons as they gain the necessary skills and knowledge to navigate pools, lakes, and oceans safely. Building confidence in the water can open up a world of opportunities for fun and recreation, while also providing peace of mind knowing that you and your loved ones are equipped with essential water safety skills.

Developing Life-Saving Skills

Swimming is not only a recreational activity but also a life-saving skill . Accidents can happen anytime, anywhere, and having the ability to swim can make all the difference. Swim lessons teach vital water survival techniques, including proper breathing, floating, and stroke techniques, which can save lives in emergency situations. By mastering these skills, individuals of all ages can become confident and capable swimmers, ready to respond effectively and safely if faced with unexpected water-related incidents.

Promoting Physical Fitness and Well-being

Swimming is a fantastic way to stay fit and lead a healthy lifestyle. It is a low-impact exercise that works the entire body, improving cardiovascular health, muscular strength, and endurance. Whether you're splashing around with your little ones or engaging in lap swimming, swim lessons offer a fun and effective way to stay active and maintain overall physical well-being. Plus, the buoyancy of the water reduces stress on joints, making it an ideal exercise for individuals with joint pain or mobility limitations.

Fostering Social Connections

Swim lessons create opportunities for social connections and community engagement. Whether it's joining a group lesson, participating in swim clubs, or attending family swim sessions, these experiences allow individuals of all ages to connect with others who share a passion for swimming and water activities. Building friendships, encouraging teamwork, and fostering a sense of belonging can make the swim lesson journey even more enjoyable and rewarding.

Whether you're a child taking your first strokes or an adult seeking to enhance your skills, swim lessons offer a wide range of benefits. From building confidence and safety to developing life-saving skills, promoting physical fitness, and fostering social connections, swim lessons are an investment in your well-being and the well-being of your loved ones. Join us on this aquatic adventure and embark on a journey that will leave you swimming with joy, confidence, and peace of mind.

Remember, water safety is a skill that lasts a lifetime, and it's never too late to start. Let's make a splash together and prioritize water safety for a lifetime of fun, fitness, and cherished memories in and around the water!

- Family Centers

- Healthy Living

- Press Releases

- Social Responsibility

- Updates & Events

- Youth Development

786-356-1516

[email protected], free shipping on all orders over $50.

The Vital Importance of Swimming Lessons: Benefits and Reasons

Updated: Sep 4, 2023

Swimming is an essential life skill that everyone should acquire. It's ideal to start learning as a child, so enroll your kids in swimming lessons at a young age. However, being an adult should never deter you from learning this valuable skill. Regardless of your age, anyone can become proficient in swimming—it's truly never too late. As a swim instructor of over 15 years, I've had the privilege of teaching people of all ages how to swim, and adults often express the most gratitude when they realize they can learn this skill later in life. Nevertheless, I still recommend beginning one's swim journey as early as possible so you or your children can begin to enjoy this skill early in life. In this article, we'll explore three compelling reasons, backed by expert insights and research, that underscore the vital importance of swimming lessons for children.

The first and most important reason, which is obvious but critically important, is drowning prevention. Drowning ranks as a top cause of child fatalities. Through swimming lessons, children acquire invaluable water safety skills, including the ability to swiftly reach the poolside, execute a safe pool exit, float, secure a breath, tread water, and master essential swimming strokes. Notably, teaching your child to swim can dramatically reduce the risk of drowning among children aged 1-4 years, with studies conducted by the National Institutes of Health indicating an impressive risk reduction of up to 88%. The comprehensive learn to swim program at Kitty Swimmers covers all these vital skills and more, ensuring that you and your family can confidently and safely enjoy vacations and pool time!

Another vital reason to prioritize swimming, is the maintenance of physical health. It serves as an exceptional form of exercise that can make staying fit enjoyable for your child. Swimming stands out as a low-impact aerobic activity, known to bolster muscle strength, enhance cardiovascular well-being, and contribute to effective weight management. A report endorsed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) underscores swimming's significance as an exercise for children, highlighting its capacity to enhance flexibility, balance, and coordination. Therefore, it's crucial to continue swimming even after your child has mastered what I refer to as the 'essential swimming skills'—the ability to take a breath and keep going (whether through floating or lifting their head) and knowing how to exit the water safely. Some parents may consider halting swimming lessons once these skills are acquired, but swimming offers more than just water safety. Learning proper swimming strokes is instrumental in physical development and fosters improved coordination.

Swimming extends its benefits beyond physical development; it also significantly impacts mental health across all age groups. This aquatic activity serves as a potent means to enhance mental well-being. The tranquil nature of swimming offers profound stress and anxiety reduction. In fact, a study featured in the International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education unveiled that swimming not only induces relaxation but also contributes to improved sleep quality and a notable reduction in symptoms associated with depression.

Children stand to gain a multitude of advantages from swimming lessons, making them an indispensable part of their growth. Lessons not only serve as a crucial safety measure against drowning but also promote physical well-being and foster mental health. Understanding the importance of swimming lessons is just the first step, now it's time to take action and get in the pool! Be sure to visit our shop for custom Kitty Swimmers gear

including swim wear for the entire family, water-resistant book bags for swim gear or back to school needs, sun protecting rash guards, shirts, and more.

Written by Cat V.

Recent Posts

3 Things You Should Do After Swimming Lessons

Navigating Open Water Safety: A Guide to The 5 Coast Guard-approved Flotation Devices

Why Children Should Never Wear Floaties In The Pool

Why Swimming is Important: Top Benefits and Insights

By: Author Paul Jenkins

Posted on April 5, 2023

Categories Self Improvement

As a daily swimmer, in the pool year-round and the sea in summertime (we’re lucky enough to live near the coast), this topic is close to my heart in more ways than one!…

Swimming is an essential skill with numerous physical and mental health benefits for individuals of all ages. As a low-impact exercise, swimming enables people to engage in almost every major muscle group, including their arms, legs, torso, and stomach, improving muscle strength and endurance.

Swimming increases one’s heart rate without putting undue stress on the body and promotes a healthy metabolism and cardiovascular system (Livestrong) . In addition, regular participation in swimming can contribute to reduced stress levels, decreased anxiety and depression, and improved sleep patterns (Just Swim) .

For people with medical conditions such as fibromyalgia, swimming can help alleviate anxiety, and warm water exercise therapy can reduce depression and enhance overall mood (CDC) . These factors, combined with the positive impact swimming has on mental health in pregnant individuals, make it an important addition to any wellness routine.

Physical Benefits

Cardiovascular fitness.

Swimming is an excellent workout that helps improve cardiovascular fitness by increasing heart rate without causing stress on the body. As a result, it helps to strengthen the heart and allows for better blood circulation throughout the body. Swimming increases heart rate and promotes cardiovascular strength.

Muscle Strength

Swimming also provides a whole-body workout and engages practically all of the muscles. According to healthdirect , swimming can strengthen nearly every muscle in the body while simultaneously working the core to develop stability. This full-body resistance exercise ultimately improves muscle strength and endurance over time.

Flexibility

Swimming helps improve flexibility by requiring the body to move through a full range of motion while performing various strokes in the water. The stretching and lengthening of muscles during swimming lead to increased flexibility and can also help reduce the risk of injury.

Joint flexibility, in particular, can be improved due to the low-impact nature of swimming exercises. This, in turn, can help promote daily mobility and overall physical well-being.

Low Impact Exercise

One of the significant advantages of swimming as a form of exercise is its low-impact nature. Swimming in water relieves pressure on weight-bearing joints, such as the knees and ankles. As a result, it is an ideal activity for individuals with joint issues, arthritis, or those recovering from injuries. healthdirect states that swimming is gentle on the joints while still providing the benefits of a full-body workout.

Mental Benefits

Stress reduction.

Swimming is an effective way to relieve stress and tension due to its repetitive and rhythmic nature. According to a study , 74% of respondents said swimming helps them release stress and tension. The soothing effect of water can also contribute to the feeling of relaxation.

Mood Improvement

Regular swimming has been shown to improve mood in both men and women. Swimming can decrease anxiety and improve overall mental well-being in individuals with fibromyalgia. Moreover, swimming releases endorphins, known as happiness hormones, leading to an instant mood lift, as stated by Calmsage .

Cognitive Function

Swimming has positively affected cognitive function by slowing down dementia and cognitive decline. According to Just Swim , swimming has helped reduce anxiety and depression symptoms in 1.4 million adults in Britain, thus enhancing overall cognitive health.

Developing Discipline, Focus, and Drive

Swimming, like other sports, can help individuals develop discipline and focus by setting goals and working towards achieving them. The repetitive nature of swimming strokes encourages a meditative state, promoting mental concentration and focus.

Swimmers often develop a strong drive for self-improvement and a sense of accomplishment, positively impacting areas outside the pool, such as personal and professional life. As a result, swimming can contribute to overall personal growth and development.

Safety and Survival

The importance of swimming for all ages.

Swimming is an essential life skill that can benefit people of all ages. It improves heart health and strengthens the lungs, and helps increase oxygen circulation throughout the body, which can be crucial in emergencies (Metro League) . Teaching children basic survival skills from a young age is particularly important, as this equips them with the knowledge necessary to stay safe when near or in water (Jackson Health) .

Preventing Drowning and Accidents

Drowning can happen quickly and silently, making it vital for everyone to learn how to swim and be aware of their surroundings in aquatic environments (American Red Cross) . Adequate water safety education can help reduce the risk of injury or drowning in home pools, hot tubs, beaches, oceans, lakes, and rivers. Furthermore, it can minimize accidents in everyday situations, such as bathtubs and even buckets of water.

Water Safety Skills

Learning water safety skills not only helps individuals to protect themselves but also helps others in danger without risking their own lives. Survival swimming skills teach older children how to swim to safety if they accidentally fall into the water, and safe rescue skills enable them to assist someone in trouble (RNLI International) .

Key water safety skills to learn include:

- Proper entry and exit from the water.

- Float and tread water for an extended period.

- Swim at least 25 yards (23 meters) to safety.

- Recognize and respond to signs of distress.

- Perform a safe, non-contact rescue.

Educating oneself about water safety and honing these skills can significantly reduce the risk of accidents and fatalities in aquatic environments.

Social Aspects

Group activities.

Swimming is a great way to participate in group activities that strengthen social bonds and encourage teamwork. Group swimming lessons, for example, allow children and adults to interact with others who share a common interest in swimming. This can lead to new friendships and a sense of camaraderie among participants.

Swimming can also be enjoyed with family and friends as a fun, recreational activity. Many swimming pools and water parks offer attractions like water slides, wave pools, and lazy rivers, which can be enjoyed together, creating a space for relaxation, enjoyment, and quality time spent with loved ones.

Building Confidence

Accomplishing swimming goals, such as learning new strokes or improving one’s performance, can significantly boost an individual’s self-confidence. Mastering a new skill or achieving a personal best in swimming can instill a sense of pride and accomplishment. Additionally, overcoming fears or hesitations related to swimming, such as a fear of deep water, can help individuals build resilience and self-esteem.

Participating in group swimming lessons can be invaluable for young children’s social development. They can develop essential life skills as they learn how to interact, cooperate, and be confident around different personalities. This acquired confidence can then carry over to other areas of their lives, such as school and social settings.

Swimming as a Lifelong Skill

Swimming is a versatile and essential skill that benefits individuals from childhood to adulthood. This section highlights the age-inclusivity of swimming, its role in health and fitness maintenance, and the importance of mastering this activity to enrich daily life.

Age Inclusivity

Swimming is a skill that spans multiple age groups, making it an inclusive form of exercise and recreation. Swimming benefits all ages, from infants learning water safety to seniors maintaining physical health. Its low-impact nature accommodates joint health concerns in older adults, while its ability to improve motor skills and coordination benefits children during their developmental years.

Health and Fitness Maintenance

Swimming is an invaluable asset in maintaining overall health and fitness. As a full-body workout, swimming strengthens muscles, improves cardiovascular endurance, and increases flexibility CDC . Moreover, it aids in combating chronic health issues such as obesity, heart problems, and diabetes Swim Strong Foundation .

Beyond its physical advantages, swimming bolsters mental health. This activity has been shown to alleviate anxiety, enhance mood, and even provide therapeutic benefits to individuals with fibromyalgia CDC . Expectant mothers can also benefit from the positive effects swimming has on mental health during pregnancy CDC .

Life Skills and Confidence

Swimming teaches valuable life skills and instills confidence in individuals, regardless of age. Swimming promotes personal development as a crucial life skill, allowing children and adults to overcome fear and gain a sense of accomplishment when mastering water-related exercises The Noodies .

As one progresses in their swimming abilities, they acquire essential water safety knowledge, which can save lives in unforeseen circumstances. Whether swimming recreationally or competitively, mastery of this skill proves indispensable both in and out of the water.

Swim Lessons Save Lives. Should Schools Provide Them?

- Share article

As summer draws near, kids are increasingly likely to find themselves in or near the water. To some, this is a much anticipated opportunity for recreation and physical activity. But for those who can’t swim, being around water poses a serious threat of drowning.

One state lawmaker wants to change this, and she’s eyeing the school curriculum as the vehicle for action.

Maryland Del. Karen Toles (D-District 25) this April introduced HB 1105 , which would have required the state education department to develop a curriculum for an elective course in water safety and swimming for public school students in grades 8 through 12.

“It’s something that’s needed. I don’t know how to swim myself,” said Toles. “You look at many children throughout Maryland, particularly in the Black community, and historically, it’s not something parents passed down to their children. It’s a skill our children need to have.”

The bipartisan bill died in committee in this year’s legislative session; Tole suggested that its late introduction was partly to blame. (It was introduced on February 10.) But the effort wasn’t a complete flop. It raised awareness among the public and policy makers of the importance of learning to swim for safety’s sake, an issue that’s particularly pressing for students of color, who are far less likely to know how to swim and who drown at a much higher rate than their white peers.

The bill follows legislative efforts in other states to incorporate swimming into the school curriculum. In 2014, then-Rep. Karen Clark introduced a bill in Minnesota that would require public schools to provide swim lessons for K-12 students. The bill did not become law and swimming is not a graduation requirement in Minnesota, according to Kevin Burns, spokesperson for the Minnesota Department of Education. While a few individual schools and districts nationwide do require students to learn how to swim, there are still no statewide laws requiring schools to provide swimming lessons as part of their curriculum. Nevertheless, Toles said the recently proposed bill in Maryland has galvanized support from sources that could serve as future partners in such an initiative.

Staunch support for the initiative

One such supporter is Maryland’s Prince George’s County’s Department of Parks and Recreation.

“We’re really excited that Delegate Toles is advocating for this vital education and skill building opportunity for students in the state,” said Tara Eggleston Stewart, the division chief for aquatics and athletic facilities for the Prince George’s County Department of Parks and Recreation Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission. “We in PG County serve a predominantly African American and Latino resident population. Those communities are at most risk for drowning and water-related injuries,” she said.

The Prince George’s parks and recreation department has, since 2011, partnered with its local school system to address this problem. It began with a $5,000 grant from the USA Swimming Foundation’s Make a Splash program, a national initiative to bring water safety and education to underserved populations.

Initially, the department worked with a few schools close to its aquatic facilities to offer water safety education as well as swimming instruction at its facilities free of charge during the school day. The county school system provides bus transportation to and from the pools for participating 2nd graders. The parks and recreation department funds swim instructors and, for any student who needs them, goggles and swimsuits. The growing program currently serves 25 local schools and 1,450 students, and Eggleston Stewart hopes to expand it to 45 schools by the 2023–2024 school year.

“We teach important education skills in the school system around math, science, English, and so forth. Learning to swim is really a life-saving skill,” said Eggleston Stewart.

Challenges to launching swim requirements

Partnerships like the one between Prince George’s County’s schools and its park and recreation department illustrate how a bill like the one Toles proposed can be executed. It also shows how many pieces need to align to make it happen. Such efforts require staunch advocates like Eggleston Stewart and ample resources—PG County’s agency operates 14 facilities with pools. Some counties have far fewer. Participating school systems must also be willing and able to support the initiative. Like many school systems around the country, Maryland has a shortage of school bus drivers ; it’s unclear how many other local school systems would be able to provide transportation to and from pools.

These complicated arrangements could be avoided if schools had pools. But, as noted by Cara Grant, the president-elect of SHAPE America, the Society of Health and Physical Educators, that’s generally not the case—a factor that likely contributed to the bill’s failure, which Tole said had bi-partisan support. “Very few schools in the state of Maryland have swimming pools in their school facility,” Grant said. “Those that do usually have a partnership with government agencies to fund them.”

One such model, Grant explained, might be the District of Columbia’s transportation department, which has partnered with D.C. public schools to create Biking for Kids —classes on pedestrian and bicycle safety held in the district’s elementary schools.

Inequitable access to swimming is at the root of the problem

While the logistical challenges of launching and maintaining swimming programs by school systems are real, so too is the danger for kids who don’t learn to swim.

Drowning is the second leading cause of injury death for children ages 5 to 14, according to the C enters for Disease Control , and not knowing how to swim is one of the biggest risk factors for drowning. Nearly 64 percent of Black children in the United States report no to low swimming ability, compared to 45 percent of Hispanic children and 40 percent of white children, according to the advocacy organization U.S.A. Swimming .

A lack of opportunity to learn how to swim is largely to blame for the disparity, fueled historically by segregated pools and fewer pools in neighborhoods where a majority of residents are Black. Plus, many cities are now experiencing lifeguard shortage s. Subsequently, Black children ages 10-14 drown in swimming pools at rates 7.6 times higher than White children, according to the CDC.

These statistics, and the support her proposed legislation has received so far, keep Toles optimistic.

“Folks are jumping on board to support my bill to provide this life saving skill,” she said. “I plan to bring it [the bill] back next year, and get even more advocates at the table.”

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Common Searches

- Summer Camp

- Job Openings

- Volunteering

How Important is Learning to Swim?

- Safety around water,

- Health & wellbeing,

If asked, most parents can immediately rattle off a list of basic life skills they instinctively know their children must learn to be safe and healthy. These lists usually include habits like looking both ways before crossing the street, washing hands with soap and water (timed by singing the “Happy Birthday” song) and eating the correct daily serving of fruits and vegetables.

But for too many parents, safety around water is not on the list; and that’s something we need to address.

Fatal drowning is the second-leading cause of unintentional injury-related death for children ages 1 to 14 years old. And, the problem is particularly acute among minority communities. African-American children ages 5 to 14 are three times more likely to drown than white children of the same age.

According to a recent national study conducted at Ys by the USA Swimming Foundation and the University of Memphis at YMCAs, 64 percent of African-American and 45 percent of Hispanic children cannot swim, compared to just 40 percent of Caucasian children . Equally concerning, 87 percent of those swimmers with no or low ability plan to go to a swimming facility at least once during the summer months and 34 percent plan to swim 10 or more times.

The Y is committed to making swimming part of the list of basic life skills and reducing water-related injuries, particularly in communities where children are most at risk, through the Safety Around Water program. This program focuses on teaching parents about the importance of water safety skills and provides more children with access to water safety lessons. These lessons teach youth valuable skills for when they find themselves in the water unexpectedly, a scary situation every child should be equipped to handle.

Looking for more tips and support?

Learn more about the Y’s Safety Around Water program .

See More About Healthy Living

Top 5 Safety Around Water Tips from the…

Bridging The Gap: Overcoming Barriers to…

Four Tips that will Save Kids' Lives This…

Four Outdoor Sports Inspiring Kids to Get…

- Terms of Use

- YMCA of the USA Privacy Notice

Essay on Swimming

Students are often asked to write an essay on Swimming in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Swimming

Introduction to swimming.

Swimming is a fun and healthy activity. It is both a sport and a way to relax. People swim in pools, lakes, and oceans.

The Art of Swimming

Swimming involves moving your body through water. You use your arms and legs to push yourself forward. There are different styles like freestyle, backstroke, and butterfly.

Benefits of Swimming

Swimming is great for your health. It strengthens your muscles and heart. It also helps you stay fit and can be a great way to make friends.

Swimming is a wonderful activity. It’s fun, healthy, and a great skill to learn.

Also check:

- 10 Lines on Swimming

- Paragraph on Swimming

250 Words Essay on Swimming

Introduction.

Swimming, a seemingly simple yet complex activity, is a multifaceted discipline that combines physical exertion, mental fortitude, and technical proficiency. It is not merely a recreational pursuit but also an essential life skill and a competitive sport.

The Art and Science of Swimming

The beauty of swimming lies in its effortless synchronization of body movements, breath control, and rhythmic coordination. It is a symphony of physics, biology, and artistry. The swimmer, acting as a lever, uses the water’s resistance to propel forward, demonstrating Newton’s third law of motion in action. Biologically, it engages multiple muscle groups, enhancing cardiovascular health and overall fitness.

Swimming as a Life Skill

Swimming is more than a sport; it’s a crucial survival skill. According to the World Health Organization, drowning is the third leading cause of unintentional injury death worldwide. Therefore, swimming education is not a luxury but a necessity, underscoring the importance of making it accessible to all.

Competitive Swimming

In the realm of competitive swimming, athletes push their physical and mental boundaries to achieve remarkable feats. It’s a test of endurance, speed, and technique. Swimmers train rigorously, perfecting their strokes, starts, and turns, and strategizing their races.

In conclusion, swimming is a versatile discipline that intertwines physical fitness, mental resilience, and technical finesse. Its significance extends beyond recreation, offering life-saving skills and a platform for athletic competition. Thus, it deserves recognition not just as a sport or hobby, but as a comprehensive discipline with far-reaching implications.

500 Words Essay on Swimming

Swimming, an activity often associated with leisure, holds a multifaceted significance in human life. It is not just a means of entertainment or a competitive sport, but a life skill and a form of physical exercise that promotes health and wellbeing.

Swimming is a perfect blend of art and science. The artistry in swimming is evident in the fluid, rhythmic movements of the body, the synchronization of breath with strokes, and the ability to maintain buoyancy. The science of swimming, on the other hand, is deeply rooted in principles of physics and biology. Understanding the concepts of drag, buoyancy, and propulsion can help swimmers improve their technique and efficiency.

Recognizing swimming as a life skill is crucial. It is not just about being able to enjoy a day at the pool or beach, but also about ensuring personal safety. Drowning is a leading cause of accidental death worldwide. Hence, learning to swim can be a potentially life-saving skill. In addition, swimming also fosters self-confidence, discipline, and a sense of achievement, especially in young learners.

Swimming and Health

Swimming offers a plethora of health benefits. It provides a full-body workout, improving cardiovascular fitness, muscle strength, and flexibility. It is a low-impact exercise, making it suitable for individuals of all ages and fitness levels. Moreover, swimming can help manage weight, reduce stress, and improve mental health.

Swimming as a Competitive Sport

Swimming has a significant place in the world of sports. It is one of the most popular events in the Summer Olympics, showcasing different styles like freestyle, backstroke, breaststroke, and butterfly. Competitive swimming requires rigorous training, strategic planning, and mental resilience. It fosters a spirit of sportsmanship, teamwork, and perseverance among athletes.

Environmental Considerations

While swimming offers numerous benefits, it’s important to consider its environmental impact. Chlorinated pools can have detrimental effects on the environment. Ocean swimming can disturb marine ecosystems if not done responsibly. Therefore, swimmers should strive to minimize their environmental footprint by following sustainable practices.

In conclusion, swimming is much more than a recreational activity. It is a life skill that ensures safety, a form of exercise that promotes health, and a competitive sport that fosters discipline and resilience. However, as we enjoy the benefits of swimming, we must also be mindful of our responsibility towards the environment. By embracing swimming in its entirety, we can enhance our physical and mental wellbeing while contributing to a sustainable future.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Surrogacy

- Essay on Stay at Resort

- Essay on Social Evils

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- [email protected]

- Login / Register

Why Schools Should Make Swimming Lessons Mandatory for Child Development

Article 24 Mar 2023 2410 0

Swimming is not only a fun and exciting recreational activity, but it is also an essential life skill that can save lives. For children, learning to swim is even more critical as it can contribute to their physical, social, and cognitive development. Unfortunately, not all children have access to swimming education, which is why schools should make swimming lessons mandatory. In this article, we will explore the benefits of mandatory swimming lessons in schools, the impact of swimming education on child development, reasons to make swimming lessons compulsory, and how schools can integrate swimming lessons into their curriculum.

Benefits of mandatory swimming lessons for students

Swimming lessons offer numerous benefits to students, including:

Promoting Physical Fitness: Swimming is a full-body workout that can improve cardiovascular health, muscle strength, and flexibility. Regular swimming lessons can contribute to a child's overall fitness level, which is crucial in combating obesity and other health problems.

Enhancing Water Safety: According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), drowning is the leading cause of accidental death in children aged 1-4 years, and the second leading cause in children aged 5-14 years. Learning to swim can help children become more confident and comfortable in and around water, reducing their risk of drowning.

Improving Cognitive Development: S tudies show that children who learn to swim at an early age have better coordination, are more confident, and have improved cognitive development. Swimming requires the use of both the left and right sides of the brain, improving neural connections and promoting cognitive development.

Boosting Social Skills: Swimming lessons offer a unique opportunity for children to socialize and make new friends. They learn to work in teams, communicate with others, and develop their social skills.

Importance of swimming lessons in schools

Incorporating swimming lessons into the school curriculum is essential for several reasons, including:

Bridging the Gap in Access to Swimming Education: Not all children have access to swimming lessons due to socioeconomic factors. Incorporating swimming lessons into the school curriculum can help bridge the gap in access to swimming education, especially for low-income families and communities.

Making Swimming Education a Priority: Making swimming lessons mandatory in schools sends a message to students and parents that swimming education is a priority. It emphasizes the importance of water safety, physical fitness, and overall health.

Encouraging Lifelong Learning: Swimming is a skill that students can use throughout their lives. By introducing swimming education at a young age, schools can encourage lifelong learning and promote healthy habits.

Reasons to make swimming lessons compulsory in schools

There are several reasons why schools should make swimming lessons compulsory, including:

Preventing Drowning: As previously mentioned, drowning is a leading cause of accidental death in children. Making swimming lessons compulsory can help prevent drowning and save lives.

Addressing the Swimming Skills Gap: In a survey conducted by the American Red Cross, 80% of Americans said they do not know how to swim, and only 56% of those who know how to swim can perform the five essential water safety skills. By making swimming lessons compulsory, schools can help address the swimming skills gap and promote water safety.

Supporting Physical Education: Swimming is an excellent addition to the physical education curriculum, offering a low-impact workout that is easy on joints and muscles. Incorporating swimming lessons into the school curriculum can support physical education and promote overall health.

Impact of swimming lessons on child development

Swimming lessons can have a significant impact on a child's development, including:

Physical Development: Swimming is a low-impact activity that can help children develop their coordination, balance, and overall physical fitness.

Social Development: Swimming lessons offer a unique opportunity for children to socialize with their peers in a fun and safe environment. Children learn to work together, take turns, and communicate effectively while participating in group activities and games. Swimming lessons can also help children build confidence and self-esteem, as they learn new skills and overcome their fears.

Improved Cognitive Development: Swimming requires the use of both the left and right sides of the brain, leading to improved cognitive development. A study conducted by the Griffith Institute for Educational Research found that children who participated in regular swimming lessons at a young age achieved significantly better cognitive and physical development milestones compared to their non-swimming peers.

Better Physical Fitness: Swimming is a low-impact exercise that offers a full-body workout, making it an ideal activity for children of all ages and abilities. Regular swimming can help improve cardiovascular health, strengthen muscles and bones, and increase flexibility and coordination. It can also promote healthy growth and development, reduce the risk of obesity, and improve overall physical fitness.

Prevention of Drowning: According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), drowning is the leading cause of accidental death in children aged 1-4 years, and the second leading cause in children aged 5-14 years. Swimming lessons can teach children essential water safety skills such as floating, treading water, and basic strokes, reducing their risk of drowning and increasing their chances of survival in case of an emergency.

Integration of Swimming Lessons into School Curriculum:

To ensure that all children have access to swimming education, schools can integrate swimming lessons into their curriculum. Schools can partner with local swimming facilities, hire certified swimming instructors, and incorporate swimming lessons into their physical education program. The National Recreation and Park Association recommends that schools prioritize water safety education and swimming proficiency by incorporating swimming into the curriculum, promoting aquatic fitness, and providing opportunities for continued swimming education.

Reasons to Make Swimming Lessons Compulsory:

Despite the numerous benefits of swimming education, many schools do not offer swimming lessons as part of their curriculum. To prevent the negative effects of a lack of swimming education in students, schools should consider making swimming lessons compulsory. Here are some reasons why:

Promoting Water Safety: As mentioned earlier, drowning is a leading cause of accidental death in children. By making swimming lessons compulsory, schools can ensure that all children receive essential water safety education, reducing their risk of drowning and increasing their chances of survival in case of an emergency.

Equal Access to Swimming Education: Swimming lessons can be expensive and often inaccessible to low-income families and communities. By making swimming lessons compulsory, schools can ensure that all children, regardless of their socioeconomic status, have equal access to swimming education.

Promoting Physical Fitness: Physical inactivity is a growing problem among children, leading to an increased risk of obesity and other health problems. By making swimming lessons compulsory, schools can promote physical fitness and overall health among children.

Conclusion:

Swimming lessons offer numerous benefits for child development, including improved social, cognitive, and physical development, as well as water safety education. To ensure that all children have access to swimming education, schools should consider making swimming lessons compulsory as part of their curriculum. By promoting water safety, equal access to swimming education, and physical fitness, schools can help children develop essential life skills and promote their overall health and well-being.

- Latest Articles

A Student's Guide to Conducting Narrative Research

April fools' day facts: origins, pranks & traditions, boosting success: the power of parental involvement in education, parental involvement in education: key to success, primary education in developing nations: overcoming challenges, why sports coaches are embracing cutting edge materials for their equipment, are we born happy exploring the genetics of happiness, list of bank holidays in nepal 2081 (2024 / 2025), how to stand out in a sea of stanford applicants, apply online.

Find Detailed information on:

- Top Colleges & Universities

- Popular Courses

- Exam Preparation

- Admissions & Eligibility

- College Rankings

Sign Up or Login

Not a Member Yet! Join Us it's Free.

Already have account Please Login

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Children (Basel)

- PMC10453388

The Impact of Swimming on Fundamental Movement Skill Development in Children (3–11 Years): A Systematic Literature Review

Associated data.

The data presented in the study are available in the article.

Swimming is the only sport providing lifesaving skills, reducing the risk of death by drowning, a top cause of deaths in children aged 1–14 years. Research shows swimming amongst other sports can aid fundamental movement skill (FMS) development. Therefore, this review investigated the following: (1) how swimming impacts FMS development in children aged 3–11 years, (2) successful tools assessing swimming and FMS, and (3) recommendations appropriate to the UK curriculum based on findings of this study. A systematic literature review using Google Scholar, PubMed, and SPORTDiscuss was conducted to investigate the effects of swimming on FMS development. Methods included database searching, finalising articles appropriate to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and identifying relevant articles using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool assessed data quality and bias risk, whilst thematic analysis synthesised data alongside descriptive results. Ten papers were synthesised, identifying significant positive impacts of swimming on FMS, including significant pre–post testing ( p < 0.01), significant improvements compared to other sports ( p < 0.001), and significant improvements in specific motor skills (Balance; p = 0.0004). Future research specifically addressing swimming and FMS is essential to improving the curriculum.

1. Introduction

Current research on fundamental movement skills (FMS) and the impact of swimming is limited, with research considering the effects of swimming often being incorporated alongside other sports like football [ 1 ], gymnastics [ 2 ], and general physical activity (PA) [ 3 ] and in children with disabilities [ 4 ], which does not focus on swimming-specific effects on FMS development. Those limited papers that do address the effects of swimming on FMS can be dated, based overseas [ 5 , 6 ], or based on different curriculum and assessment guidelines or unreliable swimming assessment methods [ 7 ]. Previous research indicates that swimming intervention can improve FMS development [ 1 ], reduce stress and overstimulation in children with disabilities [ 4 ], and make joint manipulation easier due to reduced weight bearing.

Although limited, research supports the positive impact of swimming intervention on FMS development [ 8 , 9 ] and highlights a need for a more modern and universal swimming assessment tool [ 10 ]. This is particularly true for UK research, representative of the population, in addressing the importance of swimming within the UK curriculum and Swim England (SE; [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]). Research supporting the general benefit of swimming to FMS is non-specific, with research generalising swimming rather than breaking it down into swimming-specific skills, highlighting a gap in the literature looking at specific effects of swimming on FMS in children [ 14 ].

1.1. Swimming

Swimming can improve general health, mental health [ 15 ], cardiovascular endurance, muscular strength, flexibility, coordination, balance, and much more [ 16 ], but it also allows for children to interact with new people of a similar ability to themselves, develop new skills, and socialise [ 17 ]. Swimming is a highly inclusive sport and can be for all ages, sizes, ethnicities, and backgrounds; children or adults with disabilities can also participate in the sport, which is extremely beneficial to their wellbeing [ 18 ]. Swimming is the only sport that is a lifesaving skill [ 17 ] and is often seen as an essential life skill and sport for this reason. Currently, swimming is the only compulsory sport in the UK national curriculum [ 17 ], with schools having to provide lessons in key stage 1 or 2 (KS1 or KS2; [ 13 ]), which encourages pupils’ time in the water; however, the purpose of this is to provide general water safety such as swimming competently for 25 m and performing self-rescue [ 18 ], not to aid FMS development specifically. The government provides schools with a PE Sports Premium, used to provide equipment, lessons, and training for staff in order to deliver high-quality PE lessons in primary schools across the UK [ 19 ], with guidance suggesting where schools should allocate money to, which may be why only 53% of KS1/2 students access swimming lessons [ 11 ]. According to recent government statistics [ 14 ], local authority schools (LAS) were allocated GBP 6970.00 per pupil for the 2022–2023 academic year (GBP 6780.00 for 2021–2022), for pupils aged 5–16 years. This money is for employing staff, maintenance, equipment, and supplies. In the 2021–2022 academic year, total expenditure for UK LAS was GBP 23.1 billion [ 20 ], only 13% was spent on supplies including sports equipment. For the 2021–2022 academic year, school sports premium (SSP) funding provided five goals for primary schools to work towards [ 14 , 19 ], including increasing attainment and achieving swim competency by the end of KS2; however, this was scarcely achieved: one in four students did not reach swim competency, with only 34% meeting full competency criteria [ 11 ]. Again, the SSP provides guidance rather than policy, which allows schools to spend funds as they wish [ 21 ] and could potentially disadvantage some children who then do not access swimming lessons regularly. Guidance is provided by the government [ 14 ] and Active Partnerships [ 22 ], an organisation supported by the government to advise schools on spending which could be a contributing factor to why not all KS2 children achieve swim competency post-KS2 [ 14 ].

In recent years, the emergence of new assessment tools for swimming includes the aquatic movement protocol (AMP) [ 10 ], backed by the increasing number of children and adults dying from drowning, a preventable cause of death. In 2021, the World Health Organisation (WHO) [ 23 ] identified that drowning is a top-five cause of deaths in 1–14-year-olds in 48 of 85 countries worldwide, highlighting the significance of learning swimming not just for FMS development, but also as a lifesaving tool. The AMP [ 10 ] is one of the first tools proposed to effectively assess aquatic motor competence in young children. Whilst this study identified a significant relationship ( p = 0.01) between swimming and improved FMS, there needs to be further research to assess the test–retest reliability of the AMP, which may prove to be a useful tool that can be utilised by swimming coaches, education teachers, and sport scientists [ 10 ], especially in the UK where research is limited.

1.2. Fundamental Movement Skills

Motor development is the change or improvement in motor skills (MS); FMS competency is a prerequisite to daily functioning and participation in PA or sport-specific activities [ 24 ], primarily developed in pre-school-aged children (3–5 years) [ 25 ], a critical time for FMS development influenced by instruction and practice [ 26 ]. If a child were to not develop specific locomotor and object control skills during pre-school years, they can become limited in MS ability. Research highlights that FMS delays can mirror inactivity in adolescence [ 25 , 27 ], making everyday tasks harder, and contributes to poor coordination and motor function which are essential to daily routines in adulthood.