- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

What Is Human Subjects Research?

Department of Philosophy, Dalhousie University

- Published: 15 December 2020

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter provides an overview of the nature, scope, and practice of human subjects research. It begins by tackling the general question, “What is research?” Attempts to answer this question typically define research by its methods and/or goals, and the chapter surveys the limits of these definitions through discussion of tough boundary cases. Along the way, the chapter describes various methods (quantitative, qualitative) and types of human subjects research (clinical, social scientific, etc.). The second section of the chapter investigates who is referred to by the language of “human subjects”: which humans tend to be selected as research participants, where human subjects are located globally, and how these locations are changing. The chapter also raises questions about which subjects are considered human in this context, for instance, whether definitions include embryos, cadavers, or stem cells. Throughout, the chapter highlights the ethical issues raised by the various types of activities and subjects described.

Which of the following is human subjects research?

A clinician conducts a placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial of a new treatment for depression.

A sociologist conducts a series of in-depth interviews with paramedics and firefighters about their experiences of burnout, which are then transcribed and analyzed for common themes.

On the basis of published research indicating a reduction of adverse events, a hospital administrator implements mandatory surgical checklists in one of their operating rooms and tracks the outcomes compared to the hospital’s other operating rooms; the administrator hopes that the expected positive results will help to convince reluctant hospital staff to adopt surgical checklists.

A team of economists selects three cities, sends invitation letters to all low-income citizens in those selected cities, and then partners with local government to provide a basic income to selected individuals for three years, tracking a range of health and life outcomes.

A patient seeks care from a family physician for a rare heart condition; after several unsuccessful treatments, the physician tries an unusual combination of medications, and the patient reports feeling much better.

Same as example 5, but the physician then writes up the case for publication in a peer-reviewed medical journal.

A pediatric oncologist offers patients with an otherwise untreatable form of cancer the option to try promising new treatments that are in the earliest stages of development.

Medical students manipulate human embryos in order to learn how to extract cells for genetic tests.

A geneticist analyzes and sequences the DNA from blood samples collected decades ago from the members of a marginal population.

If you found yourself struggling to decide which of these counts as human subjects research, you are not alone: experts and newcomers to research ethics alike find this task difficult. In fact, even highly respected regulatory bodies and authors of codes of ethics struggle to articulate clear and consistent answers to this question (for examples, see the opening chapters in this handbook). And because an affirmative answer to the question is thought to determine which activities are in need of prospective ethics review, the stakes of this debate are thought to be quite high.

The difficulty of this task persists for many reasons but, in particular, because both key concepts in the question—“research” and “human subjects”—are hard to define and plagued by tough, and ever-evolving, boundary cases. In what follows, I will outline these controversies and investigate whether there might be a clear sorting mechanism for the kinds of cases just outlined. For both concepts (“research” and “human subjects”), I will show that a clear definition is hard, if not impossible, to find. But this may not be as big a problem as it seems. In order to explain why not, I will explore a common underlying assumption about the high stakes of this assessment: the presumed connection between ethics and a particular type of regulatory review in human subjects research. Clarifying this relationship will help to defuse the worry about demarcation criteria for these concepts.

What is research? This is a harder question to answer than one might expect: any answer is in danger of being either underinclusive (for instance, by focusing narrowly on medical research when similar activities are carried out by researchers in other disciplines or professions) or overinclusive (labeling everything vaguely experimental or involving human interaction as research). The Tri-Council Policy Statement (TCPS 2) in Canada begins with a reflection on the broad range of practices and activities that qualify as research, before proposing a definition:

The scope of research is vast. On the purely physical side, it ranges from seeking to understand the origins of the universe down to the fundamental nature of matter. At the analytic level, it covers mathematics, logic and metaphysics. Research involving humans ranges widely, including attempts to understand the broad sweep of history, the workings of the human body and the body politic, the nature of human interactions and the impact of nature on humans—the list is as boundless as the human imagination. For the purposes of this Policy, research is defined as an undertaking intended to extend knowledge through a disciplined inquiry and/or systematic investigation . (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada 2018 , 5, emphasis added)

The ethical guidelines provided by the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) provide a similar (though health-focused) definition and some examples of common research methods:

The term “health-related research” in these Guidelines refers to activities designed to develop or contribute to generalizable health knowledge within the more classic realm of research with humans, such as observational research, clinical trials, biobanking and epidemiological studies. Generalizable health knowledge consists of theories, principles or relationships, or the accumulation of information on which they are based related to health, which can be corroborated by accepted scientific methods of observation and inference . (2016, xii, emphasis added)

Likewise, according to the original Belmont Report in the United States, “the term ‘research’ designates an activity designed to test a hypothesis, permit conclusions to be drawn, and thereby to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge ” (National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, 1978, emphasis added).

Note first that each of these definitions would lead to a slightly different assessment of the cases outlined at the beginning of this chapter, so we can’t simply point to regulations to answer our question for us without engaging in further discussion about which regulations are correct. More to the point here, though, we can see that the following concepts tend to arise in definitions of research: scientific methods (observation, hypothesis testing, and/or inference), systematic and/or disciplined inquiry, generalizability, and contributing to knowledge. Research, it seems, is implicitly scientific research . Research is something that scientists do (as contrasted with journalists or celebrities, for instance). This qualification is supported by landmark ethical guidelines such as the original Nuremberg Code, Article 8 of which states, “The experiment should be conducted only by scientifically qualified persons” (Nuremberg Code 1949 , 182). And scientific research involves certain systematic and disciplined methods , which when used properly provide some assurance about the generalizability of results.

Does a focus on the scientific method help to sort the test cases? This seems a promising route since the scientific method is thought to be what makes results more reliable than unsystematic observation and inference, which connects to the aim of producing knowledge. The difficulty is that there are many different methods used by researchers in a range of disciplines. Each research method aims to answer a different question—some are comparative, while others try to find out why someone holds a position or acts a certain way.

Qualitative research methods involving human subjects range from those involving close contact and communication between researchers and individual subjects, which are often open-ended and dynamic, such as ethnographic studies, oral histories, narrative inquiries, focus groups, and minimally structured interviews, to more structured and less dynamic methods such as large-scale surveys and structured interviews. Qualitative research is excellent at answering “why” and “how” questions and much less focused on reporting numerical results than quantitative research. As such, it plays an important and complementary role to quantitative research: a quantitative study may determine that some percentage of elementary school teachers report feeling burned out, for instance, while a qualitative study can investigate why this occurring and how it is experienced or understood by those who self-report.

Quantitative research methods involving human subjects include case studies, case series, and n -of-1 studies, all of which focus on the description and analysis of individual cases. They include observational methods such as case–control and cohort studies, which track and compare groups of people over time (either prospectively or retrospectively). In these types of studies, subjects are not assigned to different groups but rather self-select or are otherwise independently sorted into groups (for instance, a study might follow cyclists and non-cyclists). And then there are interventional methods such as randomized controlled trials (RCTs), in which participants are assigned to intervention and control groups randomly, and, when double-blind, neither they nor the researchers involved know which group they were assigned to until the study is completed. In many domains, including economics, public policy, and medicine, the RCT design is regarded as the gold standard of quantitative methods because of its rigorous comparative design and perceived objectivity.

Quantitative clinical research, in particular, proceeds on the basis of positive results in earlier animal studies and then is carried out in phases. Phase I clinical research typically enrolls a small number of healthy subjects (20–80) and aims to determine whether a proposed intervention is safe in humans and at what approximate dose or intensity. Phase II clinical research enrolls a somewhat greater number of subjects (100–300)—this time those with the health condition the intervention aims to treat—and aims to assess both safety and efficacy (the effect under near-ideal conditions). Phase III clinical research enrolls large numbers of subjects (1,000+) and aims to determine whether an intervention is effective. This phase of research is typically the basis for national regulatory approval, meaning that the treatment can be prescribed and sold to patients in some jurisdiction once it has the support of (typically at least two) well-designed phase III trials. Phase IV, or post-marketing trials, track outcomes in the general population once a treatment is widely available.

In both qualitative and quantitative domains, there are meta-level research methods designed to amalgamate the results of research. These include literature reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses. In an effort to reach busy audiences, there are also summaries and syntheses which aim to bring together all research on a given topic and provide an overall assessment. Guidelines for practitioners in medicine often draw upon these meta-level studies, as well as expert opinion, in recommending standards of practice. And the range of methods is always expanding: some newer methods, such as cluster RCTs and umbrella trials, are discussed by Hey and Weijer in this handbook.

Generalizable Knowledge

What this wide range of scientific methods, from in-depth interviews to RCTs, have in common is that they involve a systematic or disciplined effort to produce results that contribute not just to knowledge but to generalizable knowledge —a standard interpretation of this term is “the use of information to draw conclusions that apply beyond the specific individuals or groups from whom the information was obtained” (Coleman 2019 , 248). This brings us to the aims of research, which were a common component of the definitions of research offered earlier. Each of the methods described might be thought of as contributing to generalizable knowledge, while something like trial and error in clinical practice might be aimed only at benefiting an individual patient. In order to figure out whether quality improvement efforts—such as instituting a surgical checklist in one operating room and comparing with others—count as generating generalizable knowledge, we would look to their aim. In the case as I described it at the outset, the administrator believed that they already knew the intervention would be successful at reducing rates of adverse events, based on the research evidence. The aim was to convince the healthcare team in the hospital that these results applied locally so that they would adopt the practice. This seems to be a case where the primary aim is changing local behavior rather than adding to general knowledge. This way of separating quality improvement activities from research proper has become quite popular in recent years. Scholars take different positions on whether this way of settling the matter is successful or not. This debate turns on, among other things, different ideas of what is meant by “generalizable knowledge.”

Most interpretations of “generalizable” focus on the applicability of results to people who were not in a study. But this can be tricky. An RCT with strict criteria for who is included, that tests an intervention against placebo, and that strictly controls the context in which treatment is administered (for instance, only by specialists in a highly resourced urban hospital) may produce results indicating that a particular medical treatment is effective. This sort of clean explanatory RCT is thought by many scholars to be the exemplar of a study design yielding generalizable results. But a rural physician in a low-resource area dealing primarily with elderly patients who have multiple health conditions might not regard the results of the study just described as generalizable to their patients. (And they would probably be right about this—the gap between research evidence and individual patient care is a real one, and closing or narrowing that gap is something researchers have been working on for decades. The advance of pragmatic trials is one attempt to solve this problem, for instance.) Through this example, we see some of the challenges inherent in claims made about generalizability, particularly when interpretations focus on applicability. Not all areas of scientific investigation lend themselves to the production of law-like generalizations of the sort (ostensibly) found in physics or chemistry. And very few medical interventions work for all patients, without qualification. To return to the quality improvement case, there is a sense in which knowledge is gained through the investigation—something new is learned about whether surgical checklists work in this specific location—and the knowledge is intended to generalize—for instance, across other operating rooms in that facility. Is this not (at least locally) generalizable knowledge, then? Many people seem to want to say “no” here but struggle to find a clear rationale for their position.

The challenges encountered thus far in our efforts to define research indicate that a new strategy is in order; accordingly, let’s turn back to our original question—“What is human subjects research?”—and ask why we are seeking an answer to this question. Perhaps the question is ill-conceived, or perhaps our aims will help guide us toward one of these imperfect options or even something better. What are the stakes here? Why does it matter what counts as human subjects research? Why would anyone resist having their actions labeled “research”?

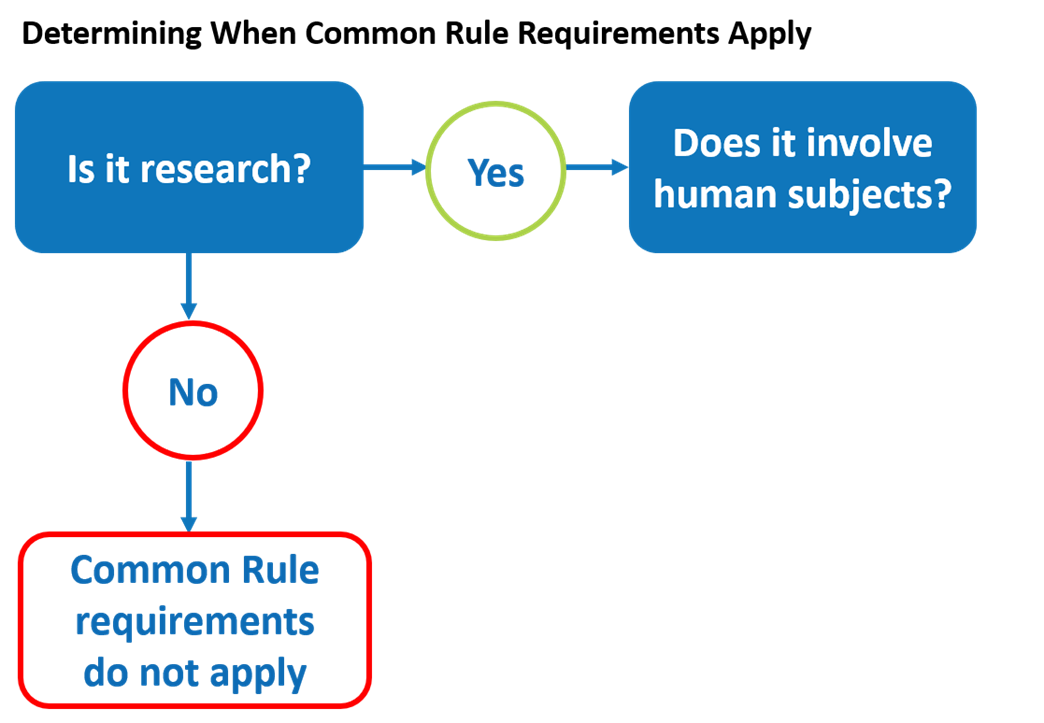

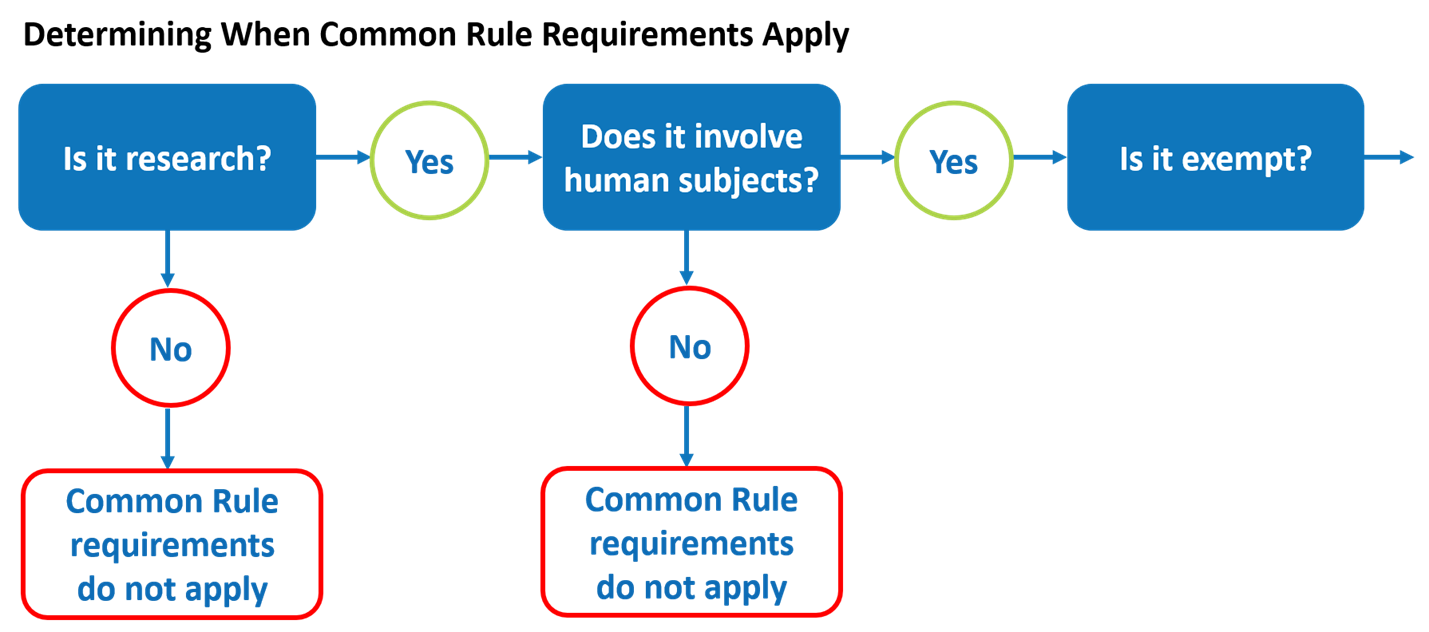

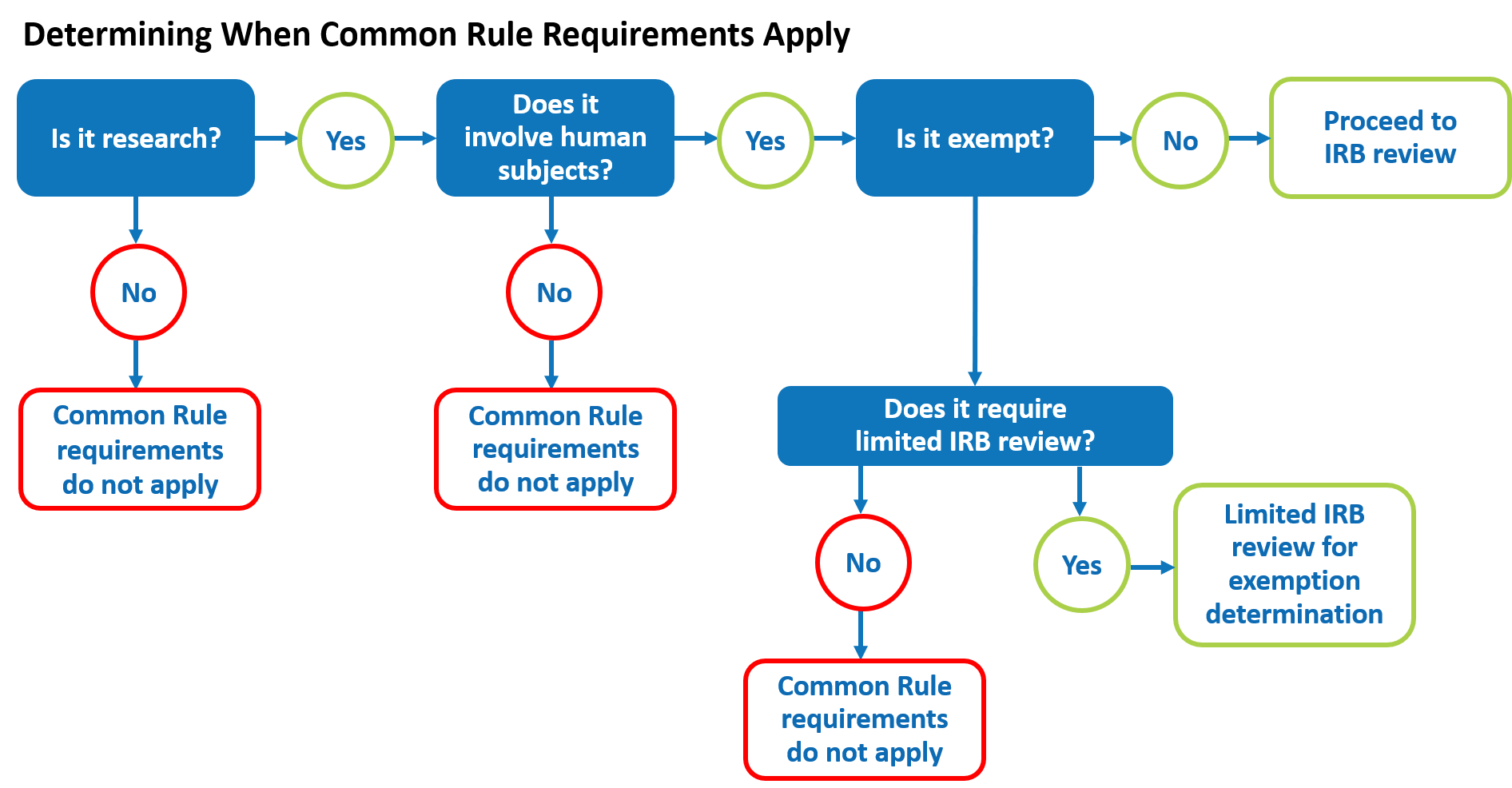

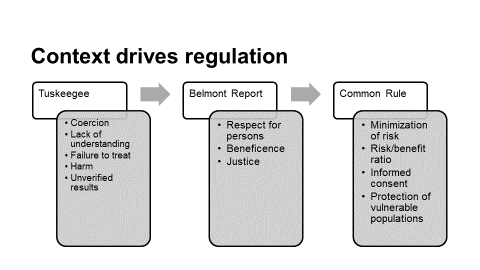

The common answer to this question—the one potential researchers themselves would likely be quick to offer—is that it matters because activities that are considered research involving human subjects must undergo review by a research ethics committee (REC) and secure approval before recruiting any participants. 1 In other words, there are regulations in most jurisdictions requiring that certain types of activities are subject to independent oversight. According to the TCPS 2 in Canada, for instance, “A determination that research is the intended purpose of the undertaking is key for differentiating activities that require ethics review by an REB and those that do not” (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada 2018 , 14). 2 A common rationale for this is that the primary aim of research is to gather knowledge to benefit people other than those in the study itself. By contrast, clinical practice, which also involves human subjects, is regulated differently (and with much less direct oversight)—by expectations that professionals will adhere to professional norms and guidelines. Because the aim of practice is benefit for the particular patient, it is thought that fewer or at least different ethical concerns arise. Similarly, other professions, like journalism, have their own sets of norms and rules guiding their activities, tied to their specific aims. The special ethical oversight of research activities is relatively new, in historical terms, since national regulations on human subjects research were enacted in most jurisdictions, in response to the public outcry over publicized cases of abuse of research subjects (for more on this, see the opening chapters of this handbook). When these regulations were proposed, those who drafted the regulations were acutely aware of the need to avoid encroaching on other domains of professional activity—particularly clinical practice (Beauchamp and Saghai 2012 ).

From the earliest attempts to offer a research–practice distinction it was clear that there would be troublesome boundary cases. 3 Phase I (or “first in human”) clinical trials—famously, those in pediatric oncology—tend to enroll patients who have cancer (not healthy subjects), and when there is no other treatment option available for that form of cancer, the research looks pretty much identical to practice (Kass et al. 2013 ). These sorts of activities might be thought of as “therapeutic research,” “innovative therapy,” or “unvalidated practice” depending on one’s orientation to the research–practice distinction. Other boundary cases recognized by early scholarship in this area included what would now be considered a type of comparative effectiveness research, in which two widely available treatments are compared to see which performs better, and quality improvement activities, in which healthcare systems experiment with new rules or guidelines in order to see how well they work in local settings (Beauchamp and Saghai 2012 , 49). Note that it is a necessary, not merely accidental, feature of such activities that they are in some sense both research and practice simultaneously. Phase IV studies are also often ambiguous—depending on how rigorously they are designed, they may also look simply like tracking adverse events in clinical practice. So while research has been defined in terms of its distinctive aim, the distinction is fuzzy and contested; and it continues to be plagued by borderline cases. 4

Note also that the way research was defined for regulatory purposes—against medical practice in particular—meant that the resulting distinction tracked the activities of greatest ethical concern in the medical context specifically. But human subjects research is a much broader category than simply medical research: there are a range of ways in which human subjects may be subjects of studies, including, for instance, in social scientific research. Because this type of research is helpful for understanding the stakes of getting the answer to the title question right, I will outline briefly the social scientific backlash to research ethics oversight, which typically involves delays associated with the prospective review of proposed research and some of the ways that ethics regulation has adjusted to accommodate the range of different types of investigations involving human subjects.

Cases from the social sciences are among the more prominent examples of controversial research in the twentieth century: the Milgram experiment on obedience to authority and Zimbardo’s prison experiment with students assigned to the role of prisoner or guard might come to mind (Haggerty 2004 ). Given that the outcry about the abuse of human subjects in medical research happened around the same time in many jurisdictions (roughly the 1970s), it is no surprise that ethics regulations were developed and applied across all domains of research with human subjects, including social science research. Resistance to these regulations is common, particularly (though not uniformly) in the social sciences, where being lumped in with medical researchers strikes many as bizarre overreach: “What began years ago as a sort of safeguard against doctors injecting cancer cells into research patients without first asking them if that was OK has turned into a serious, ambitious bureaucracy with interests to protect, a mission to promote, and a self-righteous and self-protective ideology to explain why it’s all necessary” (Becker 2004 , 415). Becker is referring here to what he calls “ethics creep,” which involves “a dual process whereby the regulatory system is expanding outward to incorporate a host of new activities and institutions, while at the same time intensifying the regulation of activities deemed to fall within its ambit” (Haggerty 2004 , 391).

A common critique raised by social scientists hinges on the inconsistency between the way different professionals, for instance, journalists and academic social scientists, are treated under current regulatory schemes. The very same activity—interviewing people, for instance—seems to trigger extensive and burdensome oversight when conducted by social scientists even though journalists proceed much more freely. In locating the problem with this arrangement, Haggerty draws attention to precisely the problem identified in this chapter, namely that central concepts like research are poorly defined in documents regarding the ethical regulation of research; they are “empty signifiers, capable of being interpreted in a multitude of ways, and occasionally serving as sites of contestation” (2004, 411). Interpretation is required, and because members of RECs feel responsible for protecting people, they tend to take what he calls a “just in case” approach, in which research is interpreted inclusively (and over-broadly) (2004, 411). This means that social scientists may be subject to extensive oversight.

In 2004, Haggerty articulated his concern as follows: “Over time, I fear that the [REC] structure will follow the pattern of most bureaucracies and continue to expand, formalizing procedures in ways that increasingly complicate, hamper, or censor certain forms of non-traditional, qualitative, or critical social scientific research” (pp. 392–393). This has also been referred to as part of the expansion of neoliberal audit culture and identified as part of the increasing bureaucratization of academia (Taylor and Patterson 2010 ). In response to this perceived ethics creep, some social scientists have called for “creative compliance” or even outright resistance to ethics regulations. One option—reclassifying one’s research as performance art (or some other unregulated activity) is offered with a wink, but behind closed doors researchers will sometimes admit using such tactics (Haggerty 2004 , 408). These efforts have in some cases been met with further regulation: “As some of us have tried new dodges to skirt the requirements, the [RECs] have wised up and closed loopholes” (Becker 2004 , 415).

Yet against these dire predictions and in response to the outcry and backlash generated by social scientists in the wake of early, more heavy-handed and medically oriented regulatory approaches, regulations (and their interpretation) have shifted in the opposite direction in many jurisdictions (for an overview of international regulations, see the chapter by Nelson and Forster in this handbook). In Canada, for instance, the most recent version of the TCPS 2 takes a proportionate approach to the review of research:

Given that research involving humans spans the full spectrum of risk, from minimal to significant, a crucial element of REB review is to ensure that the level of scrutiny of a research project is determined by the level of risk it poses to participants. … A reduced level of scrutiny applied to a research project assessed as minimal risk does not imply a lower level of adherence to the core principles. Rather, the intention is to ensure adequate protection of participants is maintained while reducing unnecessary impediments to, and facilitating the progress of, ethical research. (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada 2018 , 9)

As this statement indicates, while all research is held to the same high ethical standard, research of minimal risk is thought to require a lower degree of oversight. Ethics review in Canada begins with a determination that the activity is in fact research with human subjects; activities described as falling outside of the definition of research include the sorts of quality improvement activities outlined in the hospital administrator case and “creative practice activities” such as those undertaken by artists (p. 19). 5 Next, some activities that meet the definition of human subjects research are automatically exempt from review, including 1) research that relies entirely on legally accessible, publicly available information where the individuals have no reasonable expectation of privacy and 2) exclusively observational qualitative research conducted in public places where there is no reasonable expectation of privacy and individuals are not identified in the written report (pp. 15–18). This will cover much of the research conducted by historians and some observational studies conducted by social scientists, educators, etc.

At this point, if an activity is considered research and not exempt, it may still be afforded an expedited (“delegated”) review if it is low-risk: according to Article 6.12, “In keeping with a proportionate approach to research ethics review, the selection of the level of REB review shall be determined by the level of foreseeable risks to participants: the lower the level of risk, the lower the level of scrutiny (delegated review); the higher the level of risk, the higher the level of scrutiny (full board review)” (p. 79). In delegated review, the committee assigns one member (or some equivalently qualified person) to assess the proposal rather than assessing it all together. A negative assessment at this stage refers the study back to the full committee for review. Because social scientific research is more likely to be minimal-risk than medical research, it is well positioned to benefit from delegated review. Canada is not unique here: similar exclusions and exemptions typically exist in other national regulatory systems. And in some jurisdictions they are even broader: in the United States, for instance, public health surveillance, criminal justice, and intelligence activities are all excluded from the domain of “research” and exemptions (activities requiring only “limited review”) are offered for most interview- and survey-based research, secondary research even when it uses identifiable private information or biospecimens, and “benign behavioral interventions” (Coleman 2019 , 248). This is a more permissive approach, overall, than the one found in Canada, and the trajectory seems to be generally in the more permissive direction over time.

At this point, we have enough background about the relationship between research and regulation to return to our question about the stakes of this discussion: why would someone wish to avoid having their activity labeled research? The answer given by some investigators is that they might resist if they think there are immediate, and burdensome, regulatory implications. A few things can now be said about this. First, it may be the case that there were times and places where the burdens of regulatory oversight were heavy even in the face of minimally risky activities or where the interpretation of regulations was overzealous. But it is unlikely to be true today—most systems have built-in exemptions and expedited processes for these sorts of cases, as the Canadian example makes clear, and discrepancies in interpretation between RECs have had time to resolve. In the face of complaints from researchers, it is good to look closely at the current local regulations and the way they are implemented. Second, in some jurisdictions today there are known inefficiencies in the regulatory oversight system—this occurs for a wide range of reasons but particularly because the process typically relies on volunteer labor and can involve reading hundreds of pages of detailed, technical proposals at a time. As a result, there are sometimes long delays, and researchers are entirely within their rights to complain about this, though they should be careful about selecting an appropriate target of criticism, whether that’s the local REC or the system within which RECs operate. Further, instantaneous processing of files would be unreasonable on the part of researchers, so negotiation will be needed to find a reasonable timeline, given shared goals. 6 Finally, some of the resistance likely arises from a misunderstanding about what ethics is and how it operates in the world. This requires some attention.

For many researchers, regulatory oversight has become synonymous with ethical assessment. You might hear a hint of this when researchers talk about “getting through ethics,” “waiting for ethics,” or claiming to have “completed ethics” once they have received approval from an ethics board for their study. A similar sort of reduction of ethics to a formal process sometimes occurs in contexts where healthcare providers seek informed consent: they may talk about “consenting the patient” in advance of a procedure, for instance, which is typically reduced to having the patient sign a legal document. It is important to appreciate why this position is indefensible—why legal paperwork or regulatory approval isn’t in any meaningful way a substitute for ethics, understood properly.

To begin, consider a study that has received ethics approval and yet which, when it is actually carried out, has risks that are unreasonably high (perhaps most subjects enrolled will die) a flawed design (perhaps it is not possible to achieve statistically significant or otherwise meaningful results), subjects are told they can’t leave the study once enrolled (violating the voluntariness of their ongoing consent), or the particular individuals in the study are easily identifiable in the published final report (violating their privacy). That study is unethical, in spite of having received approval from an ethics committee. Any number of things may have gone wrong here. First, like all human activities, review is fallible, and sometimes committee members will make mistakes. Sometimes the mistake will be in applying the rules, but at other times the mistake might be in the rules themselves. The particular rules applied by any ethics committee are open to debate, discussion, and revisions in light of new developments in scientific or ethical domains. The regular updates to codes of ethics such as the “Declaration of Helsinki,” currently in its seventh revision since 1975, provide some indication of the rate of change in these domains. Second, the researchers may have provided only a general description of certain activities (such as the trial design or informed consent process) in their application to the ethics committee and then, in specifying these matters later on, made poor choices. Third, researchers may simply have deviated from what they promised to do in their application to the ethics board. The research process relies on a certain amount of trust and good will between reviewers and researchers, and this can be violated by unethical or incompetent researchers. Approval by an ethics committee, then, is not all there is to an assessment of whether some activity is actually ethical .

Awareness of this simple fact helps us to see the dangers of thinking that classifying something as research means a particular set of ethical rules applies that wouldn’t otherwise. Codes of ethics aim to identify and articulate ethical principles or rules, and ethics committees do their best to interpret and apply these general principles to particular cases. But whether those committees existed in the middle ground between principles and action or not (and until recently, they didn’t), ethical principles would still apply to certain activities whenever those activities had certain features. Research with human subjects, as noted, aims at generalizable knowledge, and it typically “uses” those subjects to get knowledge. Along the way, the subjects may be made better or worse off, and any interaction where people make others worse off raises ethical concerns about harms such as exploitation and disrespect. Think about the contrast between paradigmatic cases of medical practice and medical research here—in practice, a healthcare provider aims primarily to benefit the patient, while in research, they aim primarily to generate new knowledge. When getting new knowledge requires the use of another person’s body, it seems clear that we’re in risky ethical territory.

Another way of appreciating the scope of ethics as something far bigger than ethics regulations is to think about the fact that regulations won’t specifically state things like “don’t murder your subjects” or “don’t steal the personal belongings of your subjects” because these ethical prohibitions are thought to be covered by existing criminal laws and not in need of restating. There are many ways to be unethical beyond those listed in codes of ethics because those codes are only part of a larger social system.

Further, some of the ethical rules present in codes and guidelines arise because of the place of research within society and not merely because it is a transaction between individuals. Research proceeds only with the cooperation and support of the societies in which it is conducted, which provide funding, regulation, legal protections, social and physical infrastructure, potential subjects, and more. The requirement that research is socially valuable—that it contribute to knowledge on the topic and directly or indirectly benefits society—is one such rule imposed on research with human subjects (you can read more about this requirement elsewhere in this handbook). The requirement that research is scientifically valid—including the expectation that methods are rigorous and results are meaningful—draws on norms of science developed independently by scientists, which prioritize epistemic values such as fruitfulness, scope, and accuracy in theory construction. Scientists are also held to ethical restrictions around activities considered research misconduct, such as plagiarism, fabrication, and falsification, even though these activities aren’t listed explicitly in codes of ethics for research with human subjects.

Professional Ethics

We’ve been discussing, and trying to articulate the problems with, a particular resistance to being labeled research that results from a misunderstanding about how ethics operates in the world. Hopefully the responses to this argument have been convincing thus far. There is, however, a more nuanced version of the position remaining: some investigators might resist the research label because they believe they are governed by codes of ethics developed prior to current codes and articulated within their professions and see the bureaucracy associated with contemporary ethics review as a less nuanced and perhaps even misleading way to go about thinking through the ethical dimensions of their work. They see a perfectly functional self-regulating profession taken over by people with little or no understanding of the nature of their work or the subtle and precise responses to ethical dilemmas they’ve developed over time.

For example, journalists have ethical norms prioritizing the protection of sources—these norms evolved because of social-historical cases where harm arose (in the extreme, people who were killed when they were identified after a story was published) and a recognition of the need to avoid those harms going forward. This ethical rule for journalists is tied to what is valuable about the activity (here: truth) and a recognition of particular harms that could arise in telling the truth (here: people who assisted in exposing the truth could be killed). If you want to proceed with an activity that involves interaction with other people (maybe even in some sense “uses” them to gain knowledge) but in that interaction, or afterward, those people might be harmed, you should probably ask how that harm can be minimized. Responsible professionals in a range of domains have engaged in this thoughtful work for decades and even centuries. Anthropologists, for instance, have been reflecting about the particular ethical duties arising from ethnography since the method was developed, such as the shifting loyalties that result from the close relationships formed during fieldwork, and the desire of state entities to access and direct their research to secure information from enemies during wartime (Fluehr-Lobban 2002 ).

A decisive response to these concerns is unnecessary here: it is sufficient for the purpose of this chapter that we are aware of them. It is a matter of ongoing discussion in a range of human domains whether certain activities should be regulated or not or whether they should be regulated using one set of rules or another. In general, the position taken by liberal democratic states is that professions and industries with a history of serious harm to citizens have forfeited their right to self-regulation. Research on human subjects has a sufficiently sordid history to qualify here. Whether this inappropriately covers social scientists or others will likely be a matter for further debate. For our purposes, what is important is that we recognize that ethical rules apply regardless of which set of regulations is in force (state-imposed external ethics review, professional codes of ethics, or novel alternative oversight mechanisms). So while the stakes of the discussion are high in the sense that they determine this regulatory path, they are not as high as people tend to think because the ethical rules will apply regardless. Being labeled performance art rather than research might mean you avoid filling out some forms, but it won’t on its own change the nature of your ethical obligations since those arise out of the type of activity planned and its aims and consequences.

In sum, the best response we have to the question “What is research?” is probably that research aims to produce generalizable knowledge, but it is important to recognize that this is an imperfect definition and leaves open a range of debates, including those related to the correct interpretation of “generalizability.” It is also important to recognize that answering this question may not be the best way to decide what systems of accountability ought to track the ethical issues that arise in knowledge-gathering activities; it is worth always keeping in mind that a range of regulatory mechanisms are possible. We have also defused some of the anxiety around responses to this question by tracing and responding to some of the reasons for resistance to the label. The ethical principles arising from an activity aren’t invented and dictated by RECs—they apply whether an activity is labeled research or not and whether it is regulated as such or not. There is room for critical engagement here, but at the end of the day there’s just no escaping ethics.

Human Subjects

I have indicated that there is debate over not only what counts as research, as we’ve just seen, but also who is included in our discussions of human subjects. There are two versions of the question “Who are human subjects?,” each of which raises distinct ethical issues. First, we might wonder which humans end up being research subjects. Is there a paradigm or “model human” researchers have in mind? Are there some humans on whom research is forbidden or significantly restricted? Where are human subjects located globally, and how is this changing? Is there a shortage or surplus of human subjects available for research? How many people are research subjects annually? Depending on the answers to these questions, how might we assess the fairness of the burdens and benefits of research participation? This version of the question raises issues about representation in research as well as more general concerns of distributive and social justice.

Second, we might wonder which subjects are included in discussions of human subjects research. Are any of the following included, for instance: fetuses, embryos, brain-dead humans, cadavers, human organs or tissues, reproductive tissues, or stem cells? And, particularly if some of these items are included, why stop at the boundary of the human species? What lies behind the strict demarcation between human and nonhuman animals as subjects of research? Thinking more broadly, what are the implications of various positions on this matter for research on (hypothetical) conscious, sentient robots or aliens? This version of the question raises issues of moral status. I’ll outline both of these sets of issues.

Which Humans?

The human subjects of research have not always been representative of the diversity of humanity or even of the local populations within which research was conducted. The tendency of Western researchers (white men, for the most part), prior to ethics regulations, to seek out vulnerable populations such as prisoners, children at boarding schools, hospital patients, sex workers, citizens of other countries, racial minorities, and impoverished persons (and especially people at the intersection of these categories) for inclusion in research is well documented. The attraction of these groups was precisely their vulnerability—the fact that it was difficult or impossible for them to refuse involvement, for instance. Early responses to this situation focused on protections for variously identified vulnerable populations. While these concerns persist, and took on new life when multinational research became more common in the 1990s, another concern about representation has arisen more recently: the underrepresentation of certain groups in research. While the first set of concerns track disproportionate burdens of research participation, the second set tracks the lost benefits of research participation. The ethical assessment of the former actions—essentially, preying on the vulnerable—is more easily appreciated, so I’ll say a bit about the latter problem. Failing to ensure that subjects are representative of particular groups can lead not only to missed opportunities to benefit those populations but also to direct harm when research is falsely generalized across that group, as when a drug with positive results in one group is dangerous or toxic to another.

Women were underrepresented in clinical research in the United States (and elsewhere) until at least the 1990s. As a result of improved regulations, the United States has shifted toward more equitable inclusion of women in publicly funded clinical trials, though most studies still fail to analyze results by sex/gender in spite of the recognized benefits of doing so (cf. Geller et al. 2018 ). This is a development worth noting, but it is important to keep in mind that this tracks only clinical research, funded publicly, in one country. We shouldn’t assume the underrepresentation of women in human subjects research has been resolved or even that sensible extension to related domains has been made—the selection of exclusively male mice for animal research continued for many years after these changes were made to human subjects regulation and is still the status quo in many countries and contexts (Shansky 2019 ). The attempted justification for these exclusions has been decisively refuted in the literature dozens of times. Addressing one common mistake clearly driven by outdated gender norms, Shansky reminds us, “Women, but not men, are still pejoratively described as hormonal or emotional, which curiously neglects the well-documented fact that men also possess both hormones and emotions” (2019, 825). The resulting imbalance has affected research in many fields that continue to rely on animal studies such as neuroscience, endocrinology, physiology, and pharmacology. As a result of the exclusion of female mice from neuroscience research, and because research in animals provides the foundation for clinical trials, “the current understanding of how to most effectively treat disease in humans is similarly unbalanced” (Shansky 2019 , 825).

Over the past five years, Canadian and American funding bodies have introduced new requirements for researchers to consider sex as a biological variable in animal studies, and similar efforts have been made by the European Commission (Shansky 2019 ). Of course, sex/gender is not the only characteristic that has been unequally distributed in research studies. The same arguments offered in support of ending the exclusion of female animals from animal research and women from clinical research have been marshaled in favor of improving the inclusion of children, pregnant women, and specific ethnic minority groups (for instance, particular indigenous groups in Canada) with limited success. As mentioned, these exclusions have the potential to lead to significant harm to these populations, particularly in clinical practice since interventions never tested on a population may turn out to have more harms than benefits, and the lack of information about effects of treatments in that population might leave clinicians and others uncertain about how best to act even when acting quickly is critical. It may also simply be unjust in its own right to exclude people from research that might benefit them.

In addition to the explicit long-standing exclusion of particular identifiable groups, such as women, researchers have excluded populations indirectly by, for instance, preferring subjects who are healthier, are younger, and have fewer comorbid conditions. One result of these exclusions has been an underrepresentation of elderly people in clinical research. Because underrepresentation in research means the bench-to-bedside knowledge translation gap is bigger, this likely means elderly people are missing out on certain health benefits. And they aren’t the only ones losing out on benefits: clinical research subjects are not generally representative of a large percentage of the patient population for whom the interventions are intended. For instance, Humphreys and colleagues found that “highly cited trials do not enroll an average of 40.1% of identified patients with the disorder being studied, primarily owing to eligibility criteria” (2013, 1030). Other identifiable groups who may be affected by exclusions indirectly are people whose immigration status is uncertain, people who don’t speak the local language, and people who live far from the urban centers where much research occurs. Who is overrepresented in studies, then? People from “Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic . . . societies” (Henrich, Heine, and Norenzayan 2010 , 61). The 2019 World Health Organization’s World RePORT , drawing on data from 2016, indicates that the recipients of research funding from the top 10 funders globally continue to be mostly institutions and investigators in North America and Europe working on non-communicable diseases (World Health Organization 2019 ).

While this is true today, some things are changing. Though most clinical research (approximately 70 percent) is still conducted in North America and Europe, “significant West-to-East and North-to-South shifts appear to be underway” with researchers looking increasingly to Asia, Africa, South America, and eastern Europe (Sismondo 2018 , 55). One reason this is thought to be happening is that researchers are keen to find countries where the medical system is advanced enough to locate their trials, with access to a large population, but at the lowest cost possible. According to Sismondo, costs per subject in clinical trials are estimated to be 30–50 percent lower in India than in North America or western Europe (2018, 55). Researchers are also interested in finding populations where individuals are not already taking other medications, and countries like India may have a greater proportion of subjects like this (Sismondo 2018 , 54). There are also more altruistic motives: low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) have particular health problems, and some researchers in high-income countries (HICs) may have an interest in helping to alleviate those problems, such as high rates of HIV transmission, epidemics such as the recent Ebola outbreaks, neonatal disorders, and neglected tropical diseases. Research in developmental economics suggests that these motives and effects can also be mixed in quite complicated ways: for instance, aid organizations may seek to alleviate global poverty and design studies to inform this effort but, in doing so, also reinforce the continued existence of their organization, create cycles of dependency, or perpetuate assumptions about the lack of knowledge or expertise in targeted populations.

Another reason for this global shift is that researchers often report difficulty recruiting subjects in HICs. For example, according to McDonald and colleagues ( 2006 , np), for multi-center RCTs funded by two UK funding agencies, “Less than a third (31%) of the trials achieved their original recruitment target and half (53%) were awarded an extension. The proportion achieving targets did not appear to improve over time. The overall start to recruitment was delayed in 47 (41%) trials and early recruitment problems were identified in 77 (63%) trials.” In general, “Recruitment is often slower or more difficult than expected, with many trials failing to reach their planned sample size within the timescale and funding originally envisaged” (McDonald et al. 2006 , np). This shortage of (appropriate) research subjects is of interest to research ethics because it can drive the demographic shifts just described, which raises concerns about potential exploitation of subjects in multinational studies. It also arguably lends further support to the social value requirement of research since a resource shared by all researchers (including industry researchers) is in limited supply: human research subjects. Perhaps this means lower-value research ought not to be conducted, or the bar for what counts as a sufficiently socially valuable study should be raised (Borgerson 2016 ).

The relationship between funders, researchers, and subjects is also of interest to bioethicists. One of the reasons ethical concerns arise in LMICs is that the research is often funded and designed in HICs, and this raises worries about potential exploitation. Another concern arises when the results of the research conducted in LMICs won’t benefit other people in those same populations. One of the reasons given for the increased interest in conducting research in LMICs is that populations are “treatment-naive”—this means in general they don’t have access to healthcare, and they are likely to be unable to afford whatever treatment emerges from the research if it is successful. This feature of multinational research has generated extensive discussion among bioethicists, many of whom now agree that research should be responsive to the health needs of local populations if it is to avoid charges of exploitation. Yet this worrisome overview of the global situation was provided in 2013:

Total global investments in health R&D (both public and private sector) in 2009 reached US$240 billion. Of the US$214 billion invested in high-income countries, 60% of health R&D investments came from the business sector, 30% from the public sector, and about 10% from other sources (including private non-profit organisations). Only about 1% of all health R&D investments were allocated to neglected diseases in 2010. Diseases of relevance to high-income countries were investigated in clinical trials seven-to-eight-times more often than were diseases whose burden lies mainly in low-income and middle-income countries. (Røttingen et al. 2013 , 1286)

Dandona et al. also found that research priorities were misaligned with the health needs of the local population in India specifically: “funding for some of the leading causes of disease burden, including neonatal disorders, cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory disease, mental health, musculoskeletal disorders and injuries was substantially lower than their contribution to the disease burden” (2017, 309). The gap between funding priorities and disease burden has been of interest to economists, political scientists, and bioethicists alike for many years.

A roughly 70/30 split between industry funding and other sources is common in clinical research. Of the US$1.42 billion spent on health research in India in 2011–2012, “95% of this funding was from Indian sources, including 79% by the Indian pharmaceutical industry” (Dandona et al. 2017 , 309). In the United States, “Principal research sponsors in 2003 were industry (57%) and the National Institutes of Health (28%)” (Moses et al. 2005 , 1333). Even though there seem to be shifts underway toward more industry-sponsored research in the clinical context, practicing physicians are still a vital part of research, often supplying the subjects for research: