- English Home

Research Students

The Research Student (Kenkyusei) enrollment option allows students to conduct research at a graduate school/research institute of their choosing, enabling prospective master's and doctoral students from abroad to prepare for their desired programs under faculty supervision. Such students are not, however, eligible for academic credits or degrees from Kyoto University.

Candidates for Research Student enrollment include those wishing to:

- Prepare for a master’s/doctoral program under a preferred professor’s supervision

- Intern at a laboratory for a specific period of time (1)

- Apply for PhD joint supervision as a Special Research Student (共同養成博士研究生) under the Chinese Government Graduate Student Overseas Study Program, run by the China Scholarship Council (CSC) (2)

Please note that admission schedules and eligibility vary by graduate school and laboratory, and that some programs do not accept Research Students.

Applicants for Research Student admission must contact and obtain approval from a prospective advisor (3) , who may be selected by searching the Activity Database on Education and Research or the websites of Kyoto University and its individual Faculties/Graduate Schools, research institutes, and centers. Applicants must then submit an admission form and other required documents to the University. To learn about the exact steps involved, visit the website of the graduate school of your choice or contact its administrative office . Tuition and fees are indicated on this page .

In addition to Research Student enrollment, those from Kyoto University's student exchange partner institutions (university- and department-level partners) may be eligible for Exchange Student admission. For details, please refer to the following page and consult the office in charge at your university: Exchange Students

- An individual intern's status may depend on the purpose and duration of the internship.

- For details, please read "Special research students (non-degree course)" under "Foreign government scholarships" on the following page: Scholarships

- Contact must be made via the Admissions Assistance Office, as detailed in the AAO Application Procedures, linked from the Admissions guide for graduates of overseas universities .

Applicants from overseas universities

Graduates of overseas universities wishing to enroll in a Kyoto University Graduate School as a research, master's, or doctoral student are required to contact the Admissions Assistance Office (AAO) for a preliminary review before submitting their applications.

Please refer to the following page for details: Admissions guide for graduates of overseas universities

MEXT Research Scholarship: How to Get a Master's Scholarship in Japan for Free Continuing Your Education on the Prime Minister's Dime

October 26, 2021 • words written by Emily Suvannasankha • Art by Aya Francisco

Are you open to continuing your education overseas? Does spending two to three years in Japan on the government's yen sound like a pretty sweet deal to you? If so, the MEXT Research Scholarship might just pique your interest.

It's a well-kept secret that the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, & Technology (MEXT, or Monbukagakusho ) in Japan gives out thousands of these full-ride scholarships to international students every year. In fact, there's a MEXT scholarship for just about every education level, from undergraduate and doctoral degrees to vocational training. This comprehensive guide will focus on the MEXT Research Scholarship for master's students, since that's the one I'm familiar with. I applied through an American consulate and was lucky enough to get the scholarship in 2019. I laughed, I cried, I penned a thesis amidst a worldwide pandemic. Now, at the end of my MEXT journey, I'm ready to share my advice and experiences with other potential beneficiaries of the Prime Minister.

So, how do you get your grubby paws on one of these scholarships? Honestly, it's a long road paved with bureaucracy that can be stressful to navigate, but I'll try to lower your blood pressure in this guide by laying it all out, step by step.

Who's a Good Candidate for MEXT?

Living stipend, travel expenses, embassy vs. university recommendation, should i be a research student or regular student, finding a graduate program in japan, coming up with a research idea, timeline of the application process, 1. writing your research plan, 2. filling out the placement preference form, 3. recommendation letter, 4. health certificate, 5. academic transcripts, 7. optional documents, 8. reaching out to professors, japanese and english language tests, interview tips, requesting letters of acceptance from professors, university placement, getting accepted into the grad program, congratulations, you got mext here's some advice, what is the mext research scholarship.

The MEXT Research Scholarship is a scholarship from the Japanese government that fully waives tuition for international students pursuing a master's and/or Ph.D. degree at a Japanese university. It's given out most commonly by consulates and embassies in countries with a diplomatic relationship with Japan, but some people go directly through a Japanese university. Scholars also receive a monthly living stipend.

Basically, MEXT lets you get a master's degree for free in Japan, as long as you have a strong application and a good bit of luck.

Each embassy has a predetermined — and often small — number of scholarships it's allowed to give out, so beating out the competition can be tough. For example, my consulate in Florida typically only has one slot open. Your chances will largely depend on who else is applying at the same time and place as you are, which is a roll of the dice no one can predict. But as long as you remain eligible, you can reapply again and again — which many people do — so if you really want it, don't lose hope.

Before you apply, it's probably a good idea to check whether you're even eligible. You can receive the MEXT scholarship if you're:

- A national of a country where MEXT scholarships are offered (Japanese nationals are not eligible)

- Born on or after April 2, 1987 (for the 2022 scholarship; it increases by one year every year)

- A university or college graduate who has completed at least 16 years of education

The official MEXT guidelines also state that you must pursue a degree in the same field as your previous studies or a related one, though this requirement tends to be flexible. But aside from just being eligible, who's truly a good fit for MEXT? As someone who's gone through it, I think an ideal MEXT recipient is an independent person who's relatively comfortable with Japanese culture and customs, interested enough in some topic to write a long master's thesis about it, and willing to learn to tackle the unique hurdles of life as a lone international student in Japan.

Personally, I've never grown so much or so fast as in the two years I've spent in Nagoya as a grad student. Learning a whole new set of cultural norms to navigate the intricacies of daily life in Japan alone has taken grit, perseverance, and no shortage of spur-of-the-moment vocabulary lessons. Even simple problems like fixing a power outage or finding cheap printing can turn into a physical, emotional, and financial puzzle for a non-native Japanese speaker on a student budget with no built-in family or friends nearby to rely on.

But if you're up for the extra challenge, I guarantee you'll come out a much more capable and confident person. And in exchange, you'll get a whole two to three years to travel, study, party, and make buddies from all over the world. So, if the prospect of getting a master's degree while building tons of character excites you, I say go for it!

That said, all the excitement in the world won't pay the rent. So how will you live to study another day as an empty-pocketed grad student? Happily, MEXT provides a monthly living stipend of ¥143,000 - ¥147,000, dropped directly into the Japan Post Bank account you'll open upon arrival. The small discrepancy depends on whether you're placed in a large metropolis where living is more expensive. For instance, since I live in Nagoya, the third largest city in Japan, I receive the maximum ¥147,000. You even get paid during school breaks when you're not actively taking classes, assuming you're still in Japan.

So how will you live to study another day as an empty-pocketed grad student? Happily, MEXT provides a monthly living stipend of ¥143,000 - ¥147,000.

Living on the stipend alone is totally manageable for most single people with no dependents or debt in their home countries. However, most MEXT students I know do work part-time for more spending money, or to pay off any extra expenses. I've survived both with and without a baito (part-time job) as a student and even managed to save money from the stipends without living like a monk. That said, your mileage will vary depending on your financial situation coming into Japan, as well as whether you plan to jet set off to Okinawa every weekend.

Unfortunately, you will need to bring about $2,000 of your own money in the beginning, as the stipends only kick in 1-2 months after you land. For me, I arrived in mid-September and didn't get my first stipend until the end of October. In the meantime, I had to pay for rent, insurance, food, and the many other expenses involved in moving to a foreign country myself. This delay is likely related to how schools confirm your continued presence in Japan for the stipend. My university has me hike all the way to campus to sign a sheet of paper every month, rain or shine, to ensure each payment arrives weeks later. So make sure you've got enough yen to live on until that sweet federal dough finally rolls in!

But how will you afford to get to Japan in the first place? Blessedly, for those of us from the opposite side of the world, travel expenses are also included. MEXT pays for your economy-class plane ticket to Japan and, if you want, boots you back to your country for free after graduation. This doesn't include trains to or from the airport or any extra bags, but train fare tends to be cheap, and I'd recommend packing light anyway. You'll get an invoice to pay some airport fees and taxes yourself as well, which for me amounted to about ¥8,900 each time. Also, airfare back home is only paid for once you complete the program, so any visits in between are on you.

Many students choose not to take the free ticket home and stay in Japan instead. In this case, you switch to either a Designated Activities Visa (a job-hunting visa) or a work visa if you've already gotten a job in Japan. And if you're planning on continuing MEXT to pursue a PhD in Japan (which is possible), you just apply to extend the scholarship and renew your student visa. My school's international student office confirmed my post-graduation plans about a dozen times during my last semester, so I certainly never felt alone or lost when deciding my next step.

Before Applying

Before you apply to MEXT, there are some decisions you should make so you know what to put on the application. These include whether to apply through an embassy or a university, whether you want an extra year as a research student, which grad programs you're interested in, and what you want your thesis topic to be.

First things first: You'll need to obtain a recommendation for the MEXT Research Scholarship from either a Japanese embassy/consulate general in your country or a Japanese university. Here are the differences:

- Embassy Recommendation: You apply through your local Japanese embassy or consulate general, meeting all their deadlines — which are typically earlier than university recommendation deadlines. If chosen for recommendation, the embassy sends your application to the Japanese ministry, which likely approves you for the scholarship, barring any disasters in the background check.

- University Recommendation: You search for a university in Japan that offers university recommendations for MEXT and apply directly to them, meeting all their deadlines — which are typically later than embassy recommendation deadlines. If chosen for recommendation, the university sends your application to the Japanese ministry, which likely approves you for the scholarship, barring any disasters in the background check.

You can try for either, but going through an embassy seems to be the standard method. The deadlines are earlier too, so it's often best to try applying to an embassy first and leave university recommendation as a last resort. I went through my local consulate general, so while a lot of my advice applies to both paths, this article will focus on getting a shiny embassy recommendation.

You've decided which authority you want to snag a recommendation from. But if you get that recommendation, how many years would you like your MEXT experience to last? Here's a buck-wild part of the MEXT scholarship: After landing, you don't even have to start school for a year if you don't want to. It's called being a research student, and several of my classmates have done it.

Research Student: You'll spend about three years on the MEXT Research Scholarship, receiving living stipends as long as you're in Japan and in good standing with MEXT. During your first year, while not yet enrolled in grad school, you may audit courses, take Japanese classes, and/or plan your thesis topic with your advisor. In your second and third years, once your grad program accepts you, you'll be enrolled as a regular master's student.

Regular Student: You'll spend about two years on the MEXT Research Scholarship, receiving living stipends as long as you're in Japan and in good standing with MEXT. From the moment you arrive, you'll be enrolled as a regular master's student.

Often, if MEXT recommends that you take six months of preparatory Japanese language classes before starting the master's program, that's what you'll do as a research student. Even so, frankly, there doesn't seem to be much (if any) supervision dictating what you do during that first year.

I chose not to be a research student and dove right into grad school as soon as I got to Japan. But from the looks of it, my friends who were research students enjoyed themselves quite heartily! So if you want an extra calendar year to learn Japanese, ponder what your thesis will be about, or climb Mt. Fuji with a band of other delinquents, you've got the option.

Alright, this is the part where things get real. In order to apply to MEXT, you must first sift through the tons of master's programs in Japan and pick which ones you want to attend.

If you're looking for a program taught in English, I recommend first considering programs that are part of the Japanese government's Global 30 (G30) Project . They're full-English degree programs to encourage internationalization in Japanese academia — perfect if the idea of taking master's-level classes in Japanese makes you violently ill. I attended a G30 program at Nagoya University, and almost all my courses were in English, with only a few I chose to take in Japanese.

Then, consult this School Search spreadsheet from the Japan Student Services Organization (JASSO) that lays out the characteristics of every master's program in Japan. On the same page, JASSO also has a list showing only programs taught in English (under "University Degree Courses Offered in English"). Don't let the lengths intimidate you! You can easily narrow your search parameters and weed out the programs you don't want by using the spreadsheet filters. Grab a cold beverage and take a couple hours to peruse, googling the programs that look most interesting.

There might not be a master's program that completely aligns with your undergraduate major, especially if you're looking for one taught in English. In that case, if you still want the scholarship, you may have to get creative. For example, history majors might apply to a broader Cultural Studies program, or psychology majors could consider a Japan-in-Asia program that combines international affairs and societal Japanese studies. Admittedly, liberal arts majors have more flexibility in this area than STEM majors.

You can also choose a program based on who you want to be your academic advisor. Your advisor oversees your thesis, gives you research advice, and ultimately decides whether you pass thesis defense. Since your research will probably be fairly unique, it's okay if you can't find anyone whose specialty exactly matches yours — lots of my classmates studied topics way outside of their advisors' purviews and taught the professors a thing or two. As long as their research is in the same general academic field as your thesis, you should be fine.

The best grad program for you also depends on your — at this stage, tentative — thesis topic. Though I certainly didn't have it all figured out this early in the process, I knew I wanted to research something related to Japanese language and culture. So on the placement preference form, I put down three master's programs that included professors of Japanese sociolinguistics whose research seemed at least tangentially relevant to my idea.

But how do you come up with a research idea in the first place? From what I've seen, MEXT seems to like topics that:

- Are relevant, important, and/or potentially helpful to society today.

- Relate to Japan and (theoretically) further relations between your country and Japan in some way.

Nevertheless, not all ideas that get approved fall under both of those categories. Here are some examples from the MEXT scholars in my school's Linguistics and Japan-in-Asia Cultural Studies programs:

- Correlation between use of English loanwords and views on globalization among Japanese students (topic I got into MEXT with)

- English loanwords in Japanese LGBTQ+ and mental health activism on Instagram (topic I actually ended up writing my thesis on)

- Appropriation of Chinese culture in Japan

- The history and current state of performance art in Nagoya

- Gender and sexuality in eroguro 1 manga

- Language education and policy in Cape Verde

- Experiment on the effect of listening to music on language learning and retention

- Representations of gender and girlhood in Japanese cinema

- Veganism and vegetarianism in Japan

As you can see, MEXT topics really run the gamut. In my opinion, what we all have in common is we dug deep for something we cared about. Since a master's thesis is largely self-directed, consider subjects you find yourself thinking about often without being required to. For me, that's LGBTQ+ rights in Japan and Japanese-made English, or wasei eigo (it makes me chuckle). So, after workshopping ideas with my friends, I found a way to combine those two interests and research something I gave many hoots about. Every grad student struggles with deciding their thesis topic, but if you pick something you care deeply about, you can't go wrong.

If you want to research something related to Japan (usually a good bet), think about what facets of Japanese culture intrigue you, what problems in Japan you'd like to help solve, and what unique skills or background you bring to the table that might benefit Japan.

And whether you want to do Japan-specific research or not, try brainstorming some topics you're so fascinated by that you could read about them into the wee hours of the night. After all, that is much of the grad student experience, so it helps to enjoy those hours.

Still, keep in mind that lots of people end up changing their topic well into their first or even second year of grad school. I didn't even land on my final idea until about four months before my thesis was due! And though I don't recommend waffling quite that long, you can absolutely tweak and/or overhaul your original idea with your advisor's help, if need be.

Basically, remember that while the topic you apply to MEXT with is important, it's not the be-all end-all of what you'll actually write. You just need to show the committee you can conjure up a solid-sounding research plan and have a strong idea to start out with, even if it changes over time.

Hopefully, you now have an initial idea of which graduate programs and thesis topics may appeal to you. But how much time will this application process take, exactly? If you want to apply for MEXT, prepare for the long, long haul. Embassies typically open up submissions in spring of the year before you'd enroll in grad school, so the whole ordeal takes at least a year. Make sure you've got something to do in the interim, as well as a Plan B if it doesn't work out.

According to the official MEXT guidelines, here's a rough timeline of the application process for someone who applied in 2021:

The exact dates vary between embassies, and during the pandemic, the process may differ a bit from previous years. But one thing's for sure — you'll be emailing the embassy or consulate a lot , so I suggest building a friendly rapport with whoever's on the other end of those long email chains. Not only because it's the kind thing to do, but also because it's possible they'll be one of your interviewers.

Applying for the Scholarship

Now you have an idea of what kind of program MEXT is and whether it might be a good fit for you. So if you do decide to take the plunge, here's a list of documents you'll need to prepare and things you'll need to do in order to apply for MEXT. Since the process is so lengthy and bureaucratic, I recommend setting aside at least a few months to prepare your application. This will give you ample time to research grad programs, gather all the required documents, and run your research plan by a trusted friend or mentor. Some parts, like the health certificate and recommendation letter, will take days or weeks to complete, so getting a head start will massively behoove you.

The research plan is by far the most important part of your application. It's the basis of your argument on why they should shell out the big bucks for you to study in Japan, so invest time into polishing it as much as possible.

That said, you don't have to be a genius to write a good one — I didn't have an ounce of experience in statistics or data collection when I wrote mine. Just explain in clear academic language what you want to study and how you hypothetically plan to do it.

Some common research methods I've seen are:

You can focus on one of these methods or combine multiple. Be sure to mention how your research will contribute to an existing field of study, cite your sources, and emphasize how being in Japan and/or learning from your professors will facilitate your plan.

Also, if you're proficient enough in Japanese, you can submit a Japanese version of your research plan. Personally, I translated my English plan into academic Japanese, then posted it in chunks to Lang8 — now HiNative — to have it corrected by native speakers. I toiled over this for weeks, so I wouldn't recommend it if you're not at least intermediate-advanced in Japanese already. It's definitely not necessary, especially if you want to attend an English program. But if you can pull it off, it will impress them.

If you're so inclined, you can even include a semester-by-semester or month-by-month timeline of the full two to three years of your trip. The interviewers know your plans will change somewhat once you get to Japan and you find out what's realistic — I don't even dare look back at my timeline because of how much of it didn't end up happening. So don't worry if it feels like you're drawing blueprints with your eyes closed. At this stage, they just want to see that you're dedicated enough to come up with a detailed, reasonable preliminary plan for your research.

In addition to spelling out what you want to research, you'll also need to tell MEXT where you'd like to do that research. You get to specify up to three grad programs you'd like to attend in order of priority on the Placement Preference Form . However, it's super common for the government not to pick your first choice, especially if it's a private university, so make sure you're truly okay with ending up at any of them. Also, I do recommend putting down three universities instead of just one or two. It gives the government options, which makes the embassy more likely to recommend you.

You can also fill in the name of the professor you'd want to be your advisor at each university. If you've already contacted them, great! You should email them to get their preliminary approval before the interview at least (more about that later), but at this stage you can put their name down regardless. Bear in mind that you'll submit this form again if you pass the primary screening, so you can change the universities or update the order at that time.

How will the MEXT panel tell whether you're capable enough to perform the academic feats you outlined in your proposal? Partially through a recommendation letter from the president/dean of the last university you attended or a previous academic advisor (i.e., any professor). In short, hunt down a school official who can wax poetic about your outstanding achievements and winning personality. For example, I asked my Japanese professor from undergrad to write mine. It's free format, but make sure the letter has an official-looking letterhead and signature before sending it in a sealed envelope.

Also, like with most Japan-related ventures, you'll need to score a clean bill of health. Print out the MEXT Certificate of Health and have a doctor or physician fill it out to the best of their ability. You'll be required to bend over backwards in a few unusual ways — namely the chest x-ray, blood test, and urine sample — so get this done early to leave time for the results to come back. Some doctors have been known to scratch their heads upon sight of the form, which is written in English and Japanese, and question why it wants you to do so much. Thus, I recommend going to a family doctor you know well or a trusted facility with all the necessary equipment to make it as painless of an experience as possible. Handing over your bodily fluids is never fun, but rally, trooper, it's for a good cause.

You've proven you're healthy and cool enough to impress at least one school official — but what about your grades? MEXT requires academic transcripts of any higher education you've completed, the grading scale at your previous college(s), a copy of your degree or prospective graduation certificate, and the standard MEXT application form found on your embassy's website. Japanese higher education tends to be on the lenient side when it comes to grading, so you probably don't need a 4.0 GPA, as long as your grades have been decent enough.

Since this is Japan, you'll of course also need to glue a proper 4.5 x 3.5 cm photo of your face onto the application form. If your country isn't touting a headshot booth on every street corner (unlike Japan), try ordering photos from your local drugstore and trimming one down to size. I'm pretty sure the employees at a certain Walgreens in Orlando know my face by heart after printing it so many times for Japan applications.

We've gone through all the mandatory documents you'll need to gather, but you may also include optional documents to illustrate any relevant capabilities to the panel. These include abstracts of any theses you've already written, a certificate of language proficiency (from the JLPT , TOEFL, IELTS, etc.), a recommendation letter from your employer, and/or photos or videos of art or music you've created, if it's connected to your research project.

Okay, here's the slightly intimidating part of preparing to apply for MEXT. Like I said, you have to email professors yourself to ask whether they'd consider accepting you as their advisee if you get the scholarship. Yes, this is way, way in advance. But it's okay — many professors are familiar with the long MEXT process and are used to answering this question from prospective students.

I started shooting out emails in May of 2018, after submitting my application but before the interview. The timing is up to you, but if you show up to the interview with preliminary approval from at least one professor, it will help convince them you're a safe bet.

Primary Screening

Once you've built your leaning tower of documents, it's time to send it in and wait to hear the results. The MEXT process consists of two screenings: the Primary Screening from the embassy and the Second Screening from the Japanese government. But really, your only job is to pass the primary screening by submitting a strong enough application to score an interview, and then passing that interview. After that, the embassy or consulate does the legwork for you.

Before you interview, the embassy gives everyone a timed Japanese test and a timed English test, mostly on grammar and vocabulary. Essentially, they're making sure you're proficient enough in the language you want to take classes in (English or Japanese), as well as hopefully familiar enough with Japanese to at least communicate at a beginner's level. Most of the MEXT scholars I know are not N1-N2 level at Japanese even after living here, so you don't need to blow them away. Even so, any extra talent you can whip out will inspire confidence that you're capable of surviving in Japan on your own.

So you've shown the interviewers you're capable of speaking the language you want to take grad classes in. Now for the part of the MEXT process you've probably been having nightmares about: the interview at the consulate. You can expect about a 20-30 minute interview, and if it's in person, you'll leave all your electronics in a security box at the entrance. Dress professionally, especially considering how much moolah you're asking them to give you! I wore a simple collared black dress, which went over fine. Usually there are three interviewers; I had two native Japanese speakers and a native English-speaking consulate official I'd been exchanging emails with.

失礼します "Excuse me" ありがとうございました "Thank you"

If you're able, tossing out a shitsureishimasu (失礼します, "excuse me") when you sit down and an arigatougozaimashita (ありがとうございました, "thank you") when it's over may impress them, or at least show you've looked up Japanese interview etiquette. But the main portion of the interview will be conducted in English, and they may not use Japanese with you at all. One interviewer asked me how the Japanese test was in Japanese, and I quipped that it was easy — just kidding! — which she seemed to get a kick out of. Regardless, if you don't speak any Japanese in the interview, it's typically no big deal, especially if you want to attend an English program.

Most of the interview questions are predictable, like:

- Why do you want to study this topic?

- How will your research benefit Japan?

- How confident are you in your ability to live independently in Japan?

- Why have you chosen these master's programs?

- Are these programs taught in English or Japanese?

- Have you contacted any professors at these universities yet? (Hopefully yes!)

- What's your Plan B if you don't get the scholarship?

For these questions, prepare a clean, concise answer that you can expand on if necessary. The interviewers probably aren't experts on your subject, so no need to inundate them with jargon. If you clearly explain why your research is an important contribution to the field, how flexible you are in tweaking your plan if need be, and how committed you are to being a cultural ambassador to Japan, you've done all you can do.

But as any embassy-recommended MEXT scholar can tell you, you'll probably get a hardball question asking whether you'd freak out and flee Japan if something alarming happened. For instance, mine was, "If North Korea sent a missile over Japan while you were there, what would you do?" I answered, "Well, if I'm gonna die, might as well die in Japan!" Then we all had a good laugh, and one interviewer offered to attend my funeral. So if you suspect your interviewers have a sense of humor, don't be afraid to throw in a well-timed joke. As long as you've dressed nicely and acted politely, some genuine light-heartedness can go a long way to endearing you to the panel.

Back when I applied, I was so riddled with anxiety about the interview that I wanted to be as prepared as humanly possible. So, true to my neurotic form, I typed up a 20-page document of my answers to potential questions and recited them until I could (and probably did) describe my love for the Japanese language in my sleep. And honestly, I think it helped.

You don't have to obsess over memorizing your answers quite as much as I did, but some careful forethought and rehearsal will make you feel calmer and more prepared, despite the pressure of the interview.

Second Screening

If the embassy passes you through the primary screening and recommends your application to the Japanese government, the MEXT board will be the one who gives you the final approval. Not much to worry about here in the second screening, assuming they don't discover any undeclared crime in your past.

While you're waiting for the ministry to declare you worthy, you'll need to gather Letters of Acceptance (LoA) from all the professors you put on your placement preference form. On these letters, the professors write why they're tentatively willing to be your advisor, should you be placed at their university.

My consulate gave me a template to email the professors, which they filled out and sent back as hard copies to my address. I then forwarded them to the consulate via — you guessed it — more snail mail. But I hear some universities do it all digitally now, so you may not have to lick as many envelopes as I did.

Then, once you've passed the second screening, MEXT will notify you of which university you'll be attending. It'll be one of the schools you put on your final Placement Preference Form, but other than that, the choice is up to the head honchos in the Japanese bureaucracy. For me, the news of my fate graced my inbox about six months after I passed the primary screening. Unsurprisingly, MEXT tends to place students at public universities more often than private ones. It's improbable that they'll waive expensive private school tuition for you if they can find you a spot at a cheap public university instead. For example, private Waseda University was my first choice, but MEXT sent me to my second choice, public Nagoya University. No hard feelings, Abe-san. As long as you're open to being plopped at any one of your choices (and likely slumming it at a public university like the rest of us), you're good to go.

It's almost all over — you've been approved by the Japanese government, accepted by at least one professor, and placed at a Japanese university. But before you set sail for the Land of the Rising Sun, there's one more step: applying to the master's program itself and passing any entrance exams or interviews the program may require. I sent my program the same full application I'd sent the consulate, a copy of my passport, an extra letter of reference, and my final acceptance letter from MEXT. Since I was a MEXT scholar, the admission fees were waived.

Then came a quick Skype interview, where they asked me basic questions like what I wanted to research, why I was interested in their program, and why I picked my advisor. I actually lost my voice beforehand and had to type all my answers, which one of the professors read aloud in a booming British accent (I've never sounded better!). In my program, the interviews are mostly to make sure the students speak English well. And from what I've gathered, even if you don't perform perfectly on the interview or entrance exam, you'll likely get in anyway if you're flaunting the gold seal of approval from MEXT.

If you've successfully gotten the scholarship, congratulations! Enjoy being a sugar baby of the Japanese ministry — I know I have. Here's some extra advice for your life as a MEXT scholar:

Get Your School's Help for Housing

Your university may make you live in a dorm for at least the first few months. I moved out of mine after six months because, well, I wanted to drink chūhai 2 freely in a place that wasn't crawling with undergrads. Getting your own apartment as a foreign student can be tricky, so ask for help and take advantage of any apartment-hunting services your school offers. Also, finding an English-speaking realtor at Minimini or Sumitomo — one who's used to working with international students in the area — could help you understand all the fine print and avoid unnecessary fees.

Know That Japanese Grad School Is Pretty Chill

Japanese grad school might defy your expectations, especially if you're accustomed to a more active, less passive education system. In my program, if you show up to class and do the report and/or presentation at the end of the semester, you get an A. The one time I had to take a test, the professor assured us he would not let us fail. Your experience may vary depending on whether your professors embrace a more Western or Japanese teaching style, but generally, I found it to be way more relaxed than in the U.S.

Join a "Circle" To Make Friends

If your school has an international connections club or "circle" (サークル) 3 , joining is an excellent way to make friends. Everyone there is presumably interested in socializing with foreigners, and it's likely that at least some speak English well. Before the pandemic KO'd my social life, cultural exchange events were my main way of meeting internationally-minded Japanese students outside of my all-foreigner grad program.

Never Miss the Deadlines for Proving Your Presence in Japan

As mentioned, my university requires me to sign a sheet at the student support desk every month to prove I'm still in Japan. Otherwise, my stipend doesn't come. If I sign by the first deadline in the first few days of the month, the money arrives at the end of the month. If I sign by the second deadline at the end of the month, the money comes several weeks later. This applies even during school breaks. I know people who have missed the deadlines and lost whole stipend checks, so for the sake of your wallet, try to stay on top of this.

All in all, despite my MEXT experience getting taken down a few notches by a global catastrophe, I still don't regret all the effort I put into getting here. So if you love Japan but loathe the thought of teaching English to small children on the JET Program , MEXT might be a promising option for you. It's not the easiest road to living in Japan, and you may not get the scholarship on your first try. But if you truly want to pursue a master's degree in Japan, it's worth jumping through all the hoops.

You may now be thinking about applying for this program. If so, listen to this podcast episode that we recorded. Emily shares her experience through the MEXT research scholarship that she couldn't cover in this article.

For more information, check your local embassy or consulate's website. And if the latest information isn't available yet, here's a helpful pamphlet from the Japan Student Services Organization . May the funds be with you!

A Japanese genre of art and literature focused on "erotic grotesque nonsense" and taboo subjects. ↩

A carbonated fruit-flavored Japanese alcoholic drink, derived from the words "shōchū highball." ↩

A club or group of (usually) college students or working adults with a common interest. ↩

Non-degree Research Student

- Non-Degree Research Student

International Student Admission Guide Non-Degree Research Student

<IMPORTNAT NOTICE> (June 30, 2022) When COVID-19 situation gets worse and a non-degree research student admitted to the university cannot enter Japan due to the Japanese borer measures, please note that academic supervision has to take place online.

Non-degree research students are those persons who conduct research about a specific research topic under the guidance of an academic advisor. Upon receiving permission from their academic advisor or the instructor(s) in charge of courses, Non-degree research students are allowed to attend courses related to the research topic, but they cannot earn credits nor are they eligible to receive Master's or Doctoral degrees.

Prior to application, applicants must obtain the informal consent of the prospective academic advisor to supervise the research activities during the period of non-degree research student. The applicant is not required to come to Japan for selection process because it only proceed through a document screening process. Eligibility criteria clarifies that Non-degree research students must have bachelor's degree, and it is defined that the major purpose for being a Non-degree research student is to prepare for the graduate school admission.

Application Guide etc.

Please make sure to read following Application Guide carefully before getting ready with your application.

- Application Process Overview Chart

- Application Guide for International Non-Degree Students for AY 2024 Admission

- Graduate Course Websites/Contact Information

Application Process

1) procedures:.

Proceed with the application process in accordance with following steps. For more details, please refer to the "application Guide etc." above.

- Step1. - Obtain an informal consent from your prospective academic advisor and get the reference number from him/her that is required for web application process.

- * You need to submit a "Self-Declaration on Specific Categories" filled in necessary items with your resume or research proposal to your supervisor when you request for consent. Click here to download the form. https://coi-sec.tsukuba.ac.jp/export_control/specific-categories/

- Step2. - Complete web entries for Non-degree research student.

- Step3. - Submit required documents by post.

Link to WEB ENTRY *The Web application system will be updated in late August.

2) University Prescribed Forms

- Letter of Recommendation( PDF / WORD )

- Application Checklist for International Non-Degree Research Students for AY 2024( PDF )

Application Schedule

April 2024 enrollment.

- Web application Period September 19 (Tue) to October 6 (Fri) 15:00 JST, 2023

- Submission period of application documents (Must reach us) September 19 (Tue) to October 16 (Mon) , 2023

- Announcement of selection results Early December 2023

October 2024 Enrollment

- Web application Period March 13 (Wed) to March 29 (Fri) 15:00 JST, 2024

- Submission period of application documents (Must reach us) March 13 (Wed) to April 8 (Mon) , 2024

- Announcement of selection results Early July 2023

December 2024 Enrollment

- Web application Period May 27 (Mon) to June 7 (Fri) 15:00 JST, 2024

- Submission period of application documents (Must reach us) May 27 (Mon) to June 17 (Mon) , 2024

- Announcement of selection results Early August 2024

Application Fee

Applicants can make a payment for application fee (9,800yen) only by credit card, or at convenience stores in Japan. Please check the following payment guide and proceed from either payment site.

*With regard to the payment period, please refer to 4. (3) in University of Tsukuba Application Guide. Application will be invalid unless payment is made within the required time period.

Applicants Who Need to Obtain a Student Visa

Together with the application form and other required documents, the submission of application documents for the "Certificate of Eligibility" (COE) is needed to obtain a student visa you will be required if you pass. COE application documents must be sent by post during the application period together with other application documents.

Documents required for COE application

- Certificate of Eligibility (COE) and procedures for obtaining visas (English)( PDF )

- Checklist at the filing of COE application( PDF )

- Application for certificate of eligibility (3 sheets in total) ( EXCEL ) * Handwritten applications will not be accepted.

- Application for certificate of eligibility (Entry example)( PDF )

- Request form for proxy for application for the certificate of eligibility( PDF / WORD )

- Written oath for defraying expenses( PDF / WORD )

- Written oath for defraying expenses (Entry example)( PDF )

- COE FAQs for non-degree research students( PDF )

Selection Result

- Contact Information

- Division of Student Exchange (International Student Exchange), Department of Student Affairs, University of Tsukuba

- Email: isc#@#un.tsukuba.ac.jp

- (Remove "#" from the above e-mail address before sending email.)

- *Our FAQ provides answers to the inquiries we often receive from applicants.

- Please check it before making an inquiry.

Research Student

- Hold U.S. citizenship

- Be born on or after April 2, 1989.

- Satisfy the qualification requirements for admission to a master's degree course or a doctoral degree course at a Japanese graduate school (Includes applicants who are certainly expected to satisfy the requirements by the time of enrollment)

- Be willing to learn Japanese. Applicants must be interested in Japan and be willing to deepen their understanding of Japan after arriving in Japan. Applicants must also have the ability to do research and adapt to living in Japan

- When selecting an April state date, applicants must be able to arrive in Japan between April 1, 2024 and April 7, 2024. For October selection, applicants must be able to arrive in Japan during the period specified by the accepting university within two weeks before and after the starting date of the university's relevant academic term (September or October) for that year.

FIELDS OF STUDY

Applicants should apply for the field of study they majored in at university or its related field. Moreover, the fields of study must be subjects which applicants will be able to study and research in graduate courses at Japanese universities. Traditional entertainment arts such as Kabuki and classical Japanese dances, or subjects that require practical training in specific technologies or techniques at factories or companies are not included in the fields of study under this scholarship program. A student who studies medicine, dentistry or welfare science will not be allowed to engage in clinical training such as medical care and operative surgery until he/she obtains a relevant license from the Minister of Health, Labor and Welfare under applicable Japanese laws.

- Status: OPEN - Deadline: Friday, May 24, 2024

Interview & Test Dates

- Interview Date (Virtual) : Monday, June 10 & Tuesday, June 11, 2024 (Tentative) - Written Exam: Friday, June 14, 2024

Application Forms

- Go To Content

- Study in Kobe

Research Students

Students who wish to conduct specific research on a non-credit basis may enter Kobe University as research students by obtaining approval from the appropriate faculty or graduate school. Many of those who enrol as research students do so to enhance their scholastic ability to the level sufficient for admission to master’s or doctoral programs offered by respective graduate schools. Students must obtain approval in advance from their prospective advisor/professor at Kobe University.

Eligibility

Undergraduate students.

Applicants must have a university degree (including junior college qualifications), or have successfully completed 14 years of school education outside Japan, or possess the equivalent academic qualifications as recognized by their choice of faculty.

Graduate Students (Master’s course)

Applicants must have a university degree, or have successfully completed 16 years of school education outside Japan, or possess the equivalent academic qualifications as recognized by their choice of graduate school. Those who are expected to graduate from a bachelor’s program are also eligible.

Graduate Students (Doctoral course)

Applicants must have a master’s degree or the equivalent. Those who are expected to graduate from a master’s program are also eligible.

Entrance Periods

Twice a year (April and October) for most faculties and graduate schools. (Exceptions: Faculty and Graduate School of Medicine: Every month Graduate School of Business Administration: April only)

1 year or less. This may be extended to one more year. The maximum duration should not exceed 2 years.

Selection Method

Students are selected based on the submitted documents (excluding medical forms) and an interview. However, the interview might be omitted for applicants residing overseas.

Admission requirements vary according to each Faculty and Graduate School. For details, please refer to the website of your Faculty or Graduate School of choice.

Please note: some Faculties and Graduate Schools do not accept research students.

How to Apply

1. find your future supervisor.

Faculties and Graduate schools require students to find an academic supervisor to advise them during their period of research at Kobe University. Interested students should check to see which supervisor specializes in their field of interest and contact them directly. Some Faculties and Graduate Schools may require written consent from the prospective advisor.

How do I find an academic supervisor?

- Search within the Directory of Researchers in Kobe University Directory of Researchers in Kobe University.

- If the contact information is not available on the website of the Faculty/Graduate School, contact the Student Affairs Section of the relevant Faculty or Graduate School.

2. Obtain Application Information and Application Forms

When to request.

If the contact information is not available on the website of the Faculty/Graduate School*, contact the Student Affairs Section of the relevant Faculty or Graduate School.

- Some Faculties and Graduate Schools do not disclose application information on their websites. Please contact them directly for details.

Where and how to request

Applicants can obtain application forms either by visiting the office of each Faculty and Graduate School directly or requesting by post. When requesting by post, be sure to enclose a return envelope with the necessary stamps attached. Please address this envelope to the Student Affairs Section of the respective Faculty or Graduate School. Note:

- The return envelope should be a size that can hold A4- size (Legal size) without folding the forms.

- Please attach the necessary amount of stamps to the return envelope.

- For detailed information, please check the website of the relevant Faculty or Graduate School.

When to apply

Most Faculties and Graduate Schools usually have two admission periods a year. Note:

- The following are exceptions: Faculty and Graduate School of Medicine: every month; Graduate School of Business Administration: once a year.

- Please note that the application period for those who do not live in Japan and require a visa to come is different from those who are permanent residents of Japan.

Necessary documents

- Application form, curriculum vitae, medical examination report, university/high school diplomas, academic transcripts, photos, admission fee payment record

- Some Faculties and Graduate Schools require certificates indicating the students’ Japanese language ability and a copy of the Certificate of Residence etc.

Where to apply

Send the necessary application material to the Student Affairs Section of respective Faculty or Graduate School by post. This must reach us by the deadline. Late arrivals will not be considered for admission.

4. Selection

Students are selected based on the submitted documents and an interview. However, the interview might be omitted for applicants residing overseas.

5. Acceptance

How to find out the result.

Applicants will receive an admission notice and other information by post. Inquiries by phone are not accepted.

If accepted, applicants must make the payment of admission fee by bank transfer and submit the necessary documents.

6. Prepare for Coming to Japan

Passport and visa (when applicants reside overseas).

In order to enter Japan, international students must have a passport and a “College Student Visa”. Please refer to “Procedure for Entering Japan” for details on how to apply for the visa.

Secure Accommodation

There is University housing and other accommodation that students can apply for through the university, but these rooms are limited. Please use the “Kobe University Student Apartment Search System” to look for private apartments. This system has been established with Nasic National Student Information Center for Kobe University international students. Students can also use this search system to reserve an apartment from overseas. It is available in 4 languages (Japanese, English, Chinese, and Korean) and will also support students with lease agreement. For more information please refer to “Housing information”.

Students can also search for apartment through Kobe University Co-op Service Center after arrival in Kobe.

Reserve an airplane ticket and purchase a traveler’s insurance. (Recommended but optional)

7. after arriving in japan.

- Come to Kobe University during the designated period to complete the necessary entrance procedures.

- Participate in New Student Orientation

- Classes begin

- Make payment of Tuition fees

For more information

- Intercultural Studies

- Human Development and Environment

- Business Administration

- Health Sciences

- Engineering

- System Infomatics

- Agricultural Sciences

- Maritime Sciences

- International Cooperation Studies

- Science, Technology and Innovation

- Faculty List

- Hokkaido University

Faculty of Humanities and Human Sciences, Graduate School of Humanities and Human Sciences, and School of Humanities and Human Sciences, Hokkaido University

- Graduate School

Research Student

- Undergraduate School

- Student Life

- Study Areas of Graduate School

- Master’s Course

- Doctoral Course

- International Students at HU

- Graduate Student Admission

Admission Calendar

- Master’s Course Entrance Examination

- Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies

- Department of History

- Department of Cultural Diversity Studies

- Department of Cultural Representations

- Department of Linguistics

- Department of Slavic-Eurasian Studies

- Department of Ainu and Indigenous Studies

- Department of Psychology

- Department of Behavioral Science

- Department of Sociology

- Department of Regional Science

- FAQs (Prospective Studies)

- Study Areas of School

- Undergraduate Admission

- Support for International Students

- Student Fees

- Partner Universities

- Exchange Program

At the Graduate School of Humanities and Human Sciences and the School of Humanities and Human Sciences, it is possible for students who would like to study specific fields in order to either further their studies or prepare for the entrance examination into a degree-seeking graduate program to enroll as Research Students. However, enrollment as a research student is not a pre-requisite for taking the examination for entrance into graduate programs. Research students can study their own field of interest while also attending Japanese language courses offered by the International Student Center. Research Students can enroll in April or October. While this is a one-year course, it is possible to extend one’s time as a research student by filing a “Request for an Extension of Research Period”.

Research Students conduct research under the guidance of a supervisors. When given approval from their supervisor, research students may attend regular classes (subject to the dean’s approval).

The research student system is a program which allows for students to concentrate on their research work for a set period of time without earning credits.

Japanese Page

Application

Applicants must have completed at least sixteen years of accredited secondary school education.For the updated information on the program and submission deadline, please see Application Form.

Language Proficiency

International applicants must be proficient in the Japanese language as most classes are conducted in Japanese.

Admission Procedure

Applicants should submit the pre-inquiry documents below to the Students Affairs Section within the application period. Pre-inquiry documents submitted after the deadline will not be considered. Please do not contact any professors directly. The Students Affairs Section will confirm by email that the pre-inquiry documents have been received.

Prospective applicants who are of foreign nationality are advised to refer to the “Admission of Foreign Students (kenkyusei)” (update June 12, 2023), before lodging their applications. The procedure of the following three steps is required for application.

- Pre-inquiry Pre-inquiry form, Proposed plan of study form, A certificate of Japanese language proficiency, A letter of recommendation → Download Pre-inquiry form (update June, 2023) → Download Proposed plan of study form

- Online Application Online Application site

- Submission of application form

April and October

Financial Status

There are two statuses for international students to study in Japanese universities, regarding a tuition fee waiver and exemptions of other expenses.

Kokuhi-Ryugakusei (MEXT Students by Embassy Recommendation)

A Japanese government (Monbukagakusho) scholarship student. A Kokuhi-Ryugakusei usually starts his/her career in Japan as a Kenkyusei.

To apply for a “Letter of Acceptance” for the MEXT Scholarship

In order to obtain a “Letter of Acceptance” from our Faculty, please send us the following documents BY E-MAIL, after you pass the primary selection by the Japanese embassy in your country.

- Application Form for a Letter of Acceptance on MEXT Scholarship Program (Downloadable from here)(May 31,2023 update)

- Certificate of the primary selection issued by the Japanese embassy

- The same documents as those submitted to the Japanese embassy upon application

【NOTES】 *MEXT students by Embassy Recommendation will enter the university as research students. In order to become regular degree students, MEXT students are required to take entrance examinations and be accepted to the graduate school during their period as research students. *Document screening for issuing a Letter of Acceptance usually takes around four weeks. *We will not accept your application after the deadline on Friday, August 25, 2023 . *We will inform you of the result of screening by e-mail. If you pass the screening, we will send your Letter of Acceptance by e-mail to the e-mail address listed on the “Application form for a Letter of Acceptance on MEXT Scholarship Program.” Please let us know if you would like us to send your Letter of Acceptance by postal mail in addition to sending it by e-mail.

< Where to send applicaion documents> [email protected] Please write “MEXT Scholarship Application” in the subject line and attach all the documents in PDF format.

< Deadline > Friday, August 25, 2023 5:00PM (Japan Standard Time)

Shihi-Ryugakusei

A student who is to financially support him/herself.

Contact Information

Students Affairs Section Email: [email protected] (Open 10:00-12:00 and 13:00-17:00 from Monday to Friday. Closed on Saturdays, Sundays and Public Holidays)

The University of Tokyo

Website for International Students

Research Student

Research students are those who conduct research on specific subjects at UTokyo’s faculty/graduate school. No degrees or qualifications are awarded to research students after the completion of a research term. Qualifications may vary depending on the faculty/graduate school. For details, please contact the faculty/graduate school you wish to attend.

Center for Global Education

International Student Handbook

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

The MEXT Scholarship: Absolutely Everything You Need to Know

If you’re a Japanese language student, what better way is there to get fluent than to be around native speakers?

Traveling and studying abroad is expensive—you have to consider travel costs, food , housing, transportation, tuition and a ton of other expenses.

Thankfully for Japanese learners, there’s the MEXT Scholarship.

I’m running through everything you need to know about this Japanese study abroad opportunity, from what it is and how to apply, to all the requirements you need to meet to qualify for a free semester (or more) of schooling in Japan!

A Summary of the MEXT Scholarship Japan

Eligibility for the mext scholarship, why should i apply for the mext scholarship, types of mext scholarships, research student scholarship, undergraduate student scholarship, specialized training college student scholarship, japanese studies scholarship, how do i apply for the mext scholarship, what to do if you don’t receive the mext scholarship, and one more thing....

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

The MEXT Scholarship stands for “the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Scholarship” and is also known as “Monbukagakusho.”

It’s a scholarship given out each year to help foreign students enroll in Japanese universities.

If you successfully qualify for the MEXT Scholarship, you’ll receive:

- ¥120,000 yen per month for undergraduate students.

- ¥146,000 yen per month for Japanese Intensive Course students and research students.

- ¥147,000 yen per month for master’s program students.

- ¥148,000 yen per month for doctoral program students.

- An economy class air ticket to Narita or Haneda International Airport in Japan. (Currently, the MEXT Scholarship doesn’t cover additional travel costs from the airport.)

- Application fees

- Admission fees

- Tuition fees

Roughly, you’ll receive around a minimum of $1,000 USD per month to live, eat and travel in Japan and have all your tuition costs covered.

No matter which level of the scholarship you apply for, there are two main requirements for getting accepted:

- Get recommended by a Japanese embassy or consulate general.

- Get recommended by a Japanese university of your choice that accepts you for study.

You’ll achieve the first through the application process, which requires a form to be sent to your local Japanese embassy. You’ll achieve the second by applying to different Japanese universities and noting in your submissions that you’re applying for the MEXT Scholarship Japan.

Two more key stipulations are that you must be a citizen of a country that has diplomatic relationship with Japan and you must have a valid student visa.

The application for the 2024 MEXT Scholarship Japan has now closed. Applications for the 2025 MEXT Scholarship are expected to open in April 2024, and close in June (the exact deadline date varies between embassies.)

If any (or all!) of the following apply to you, then it’s worth trying out for this golden opportunity:

- You’re interested in studying abroad in Japan .

- You want to improve your Japanese language skills through an immersive experience at a Japanese school.

- You want to attend school for free.

- You’d like to have money to live in Japan while studying in school.

- You want to travel but want to have a larger purpose or objective while doing so.

- You want to learn more about Japanese modern culture and meet Japanese people.

There are multiple types of MEXT Scholarships one could look into and each of them have unique requirements that must be met. In addition to meeting the following requirements, you’ll also need to pass one or a few examinations in order to receive a recommendation from an embassy.

This scholarship is for those who are enrolled or want to be enrolled in a master’s, doctoral or professional graduate course and want to conduct research in a particular field in Japan. Typically, these students are linguistic or cultural studies majors.

Requirements:

- Be under 35 years old.

- Be a college graduate or have completed 16 years of schooling.

- If you haven’t graduated yet, apply for this MEXT Scholarship before the expected day of departure as a scholarship holder.

This type of scholarship is for fresh high school graduates who want to start college in Japan.

- Be between 17 and 22 years old.

- Have completed 12 years of education or have a high school diploma.

- If you haven’t graduated yet, wait to apply until the year you’re expected to graduate.

This scholarship is for foreign students who wish to spend up to three years at a Japanese technical or vocational college.

This is essentially the “exchange student” scholarship. You’ll go to Japan for a certain amount of time to study, then return to your home institution.

- Be between 18 and 30 years old.

- Be enrolled as an undergraduate student in a country outside of Japan before applying and be able to return to that institution upon your return from Japan.

- Major in Japanese language or Japanese culture.

It’s worth noting that some students may be interested in a Japanese scholarship if they study particular aspects of Japan, such as economics or engineering. While you won’t qualify for the MEXT Japanese Studies Scholarship, it’d be worth looking into the JASSO Student Exchange Support Program.

Here’s a simple 10-step plan to follow in order to apply for the scholarship, which takes into account the requirements and other aspects of the application process:

- Have or acquire a passport . Depending on your home country, there are many different ways to go about this.

- Acquire a Japanese student visa .

- Be between 17 and 35 years of age, depending on which scholarship you decide to apply for.

- Be a citizen of the country you reside in and be sure that the country has diplomatic relations with Japan.

- Be aware of important dates related to applying .

- Select a university in Japan that you want to attend and submit an application to that school ahead of time. It’d be wise to apply to multiple schools of interest.

- Study past examination questions to improve your chances of getting the scholarship.

- Fill out an application online by the designated deadline.

- Submit all application materials to an Embassy or Consulate General of Japan near your area.

- Have at least an elementary level of Japanese before applying—you will need to pass a Japanese exam in most cases to receive an embassy recommendation.

Maybe you’re afraid of applying for the MEXT Scholarship and failing. Maybe you’ve received a letter telling you that you, unfortunately, don’t qualify.

Don’t fret. Students apply for scholarships of all sorts and don’t qualify for them on a daily basis. Sometimes it isn’t meant to be and you should look into other scholarship opportunities . Sometimes it isn’t meant to be right now and you can always apply for the MEXT Scholarship next year.

It’s also important to remember that you can learn Japanese without going to Japan quite easily, so if that’s a major reason that you want to apply for this scholarship, you’re in luck. In-person and online Japanese classes , courses and lessons are abundant all over the world. Some are completely free !

But even the paid options are still more affordable than studying in Japan. From tutoring sessions on italki to contextual learning through Japanese media clips with interactive subtitles on FluentU , online Japanese immersion is more accessible than ever.

Are you interested in applying for the MEXT Scholarship now that you know more about it? You’d be surprised how many opportunities there are out there for Japanese language learners who want to travel to the Land of the Rising Sun.

Maybe you’ll score this scholarship next year. Who knows? It doesn’t hurt to try and apply!

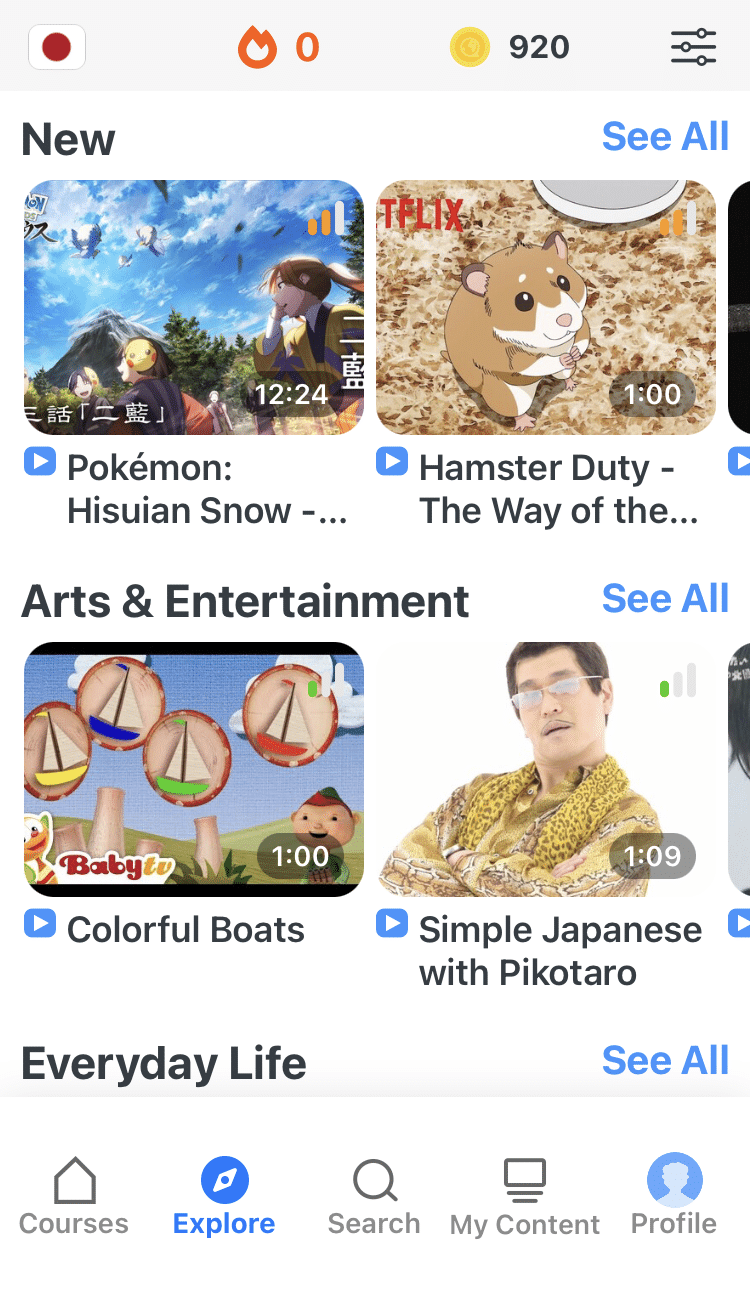

If you love learning Japanese with authentic materials, then I should also tell you more about FluentU .

FluentU naturally and gradually eases you into learning Japanese language and culture. You'll learn real Japanese as it's spoken in real life.

FluentU has a broad range of contemporary videos as you'll see below:

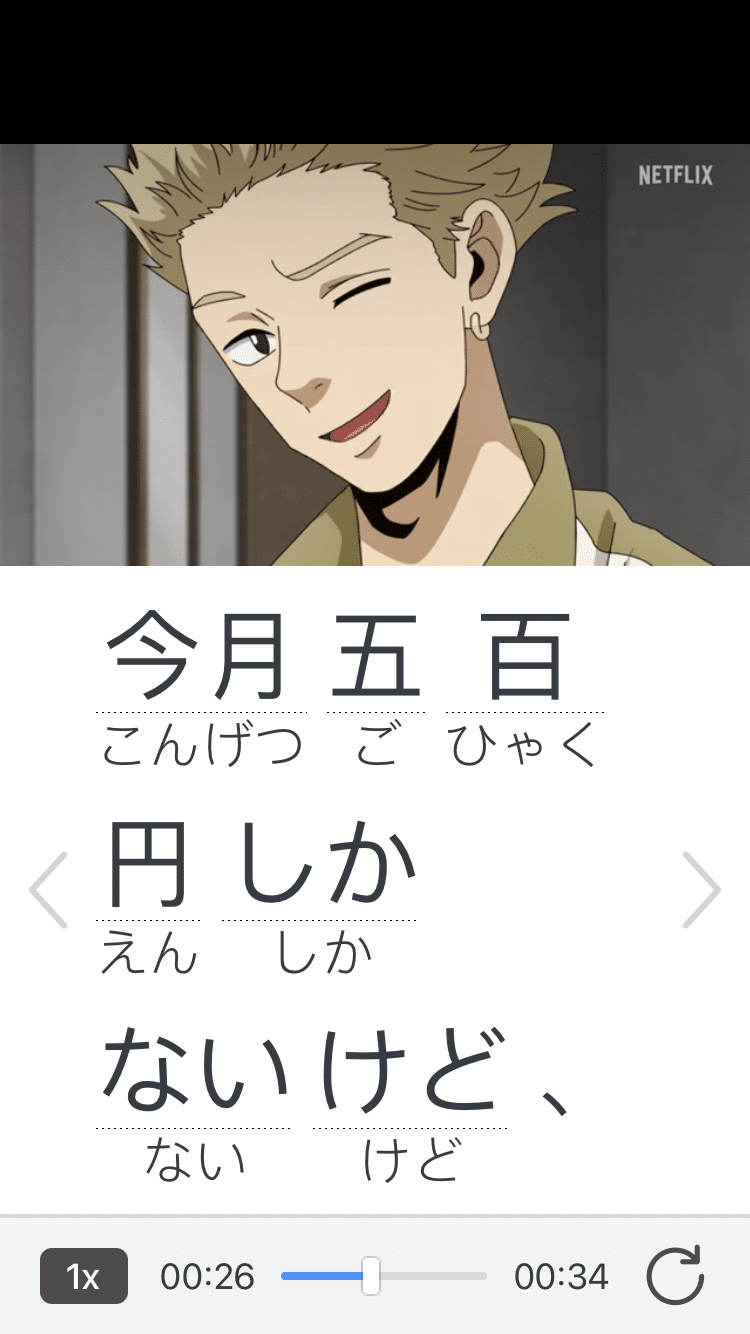

FluentU makes these native Japanese videos approachable through interactive transcripts. Tap on any word to look it up instantly.

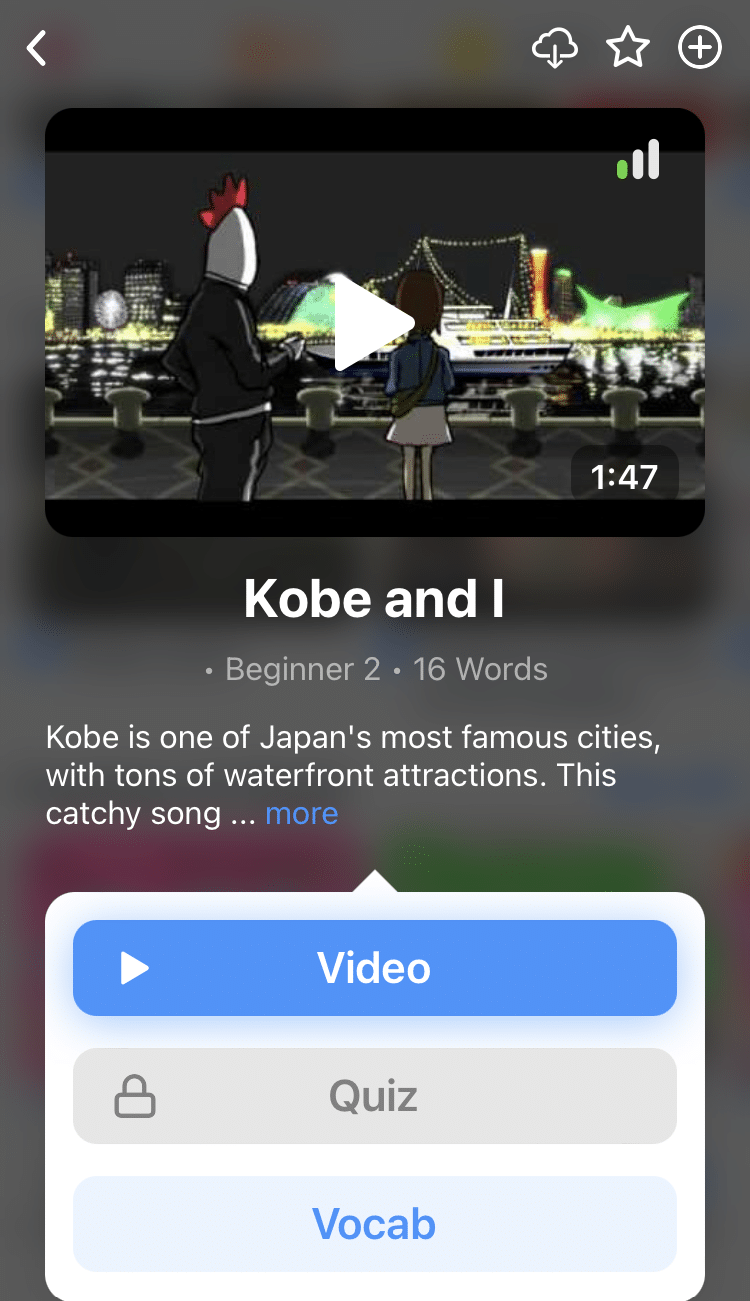

All definitions have multiple examples, and they're written for Japanese learners like you. Tap to add words you'd like to review to a vocab list.

And FluentU has a learn mode which turns every video into a language learning lesson. You can always swipe left or right to see more examples.

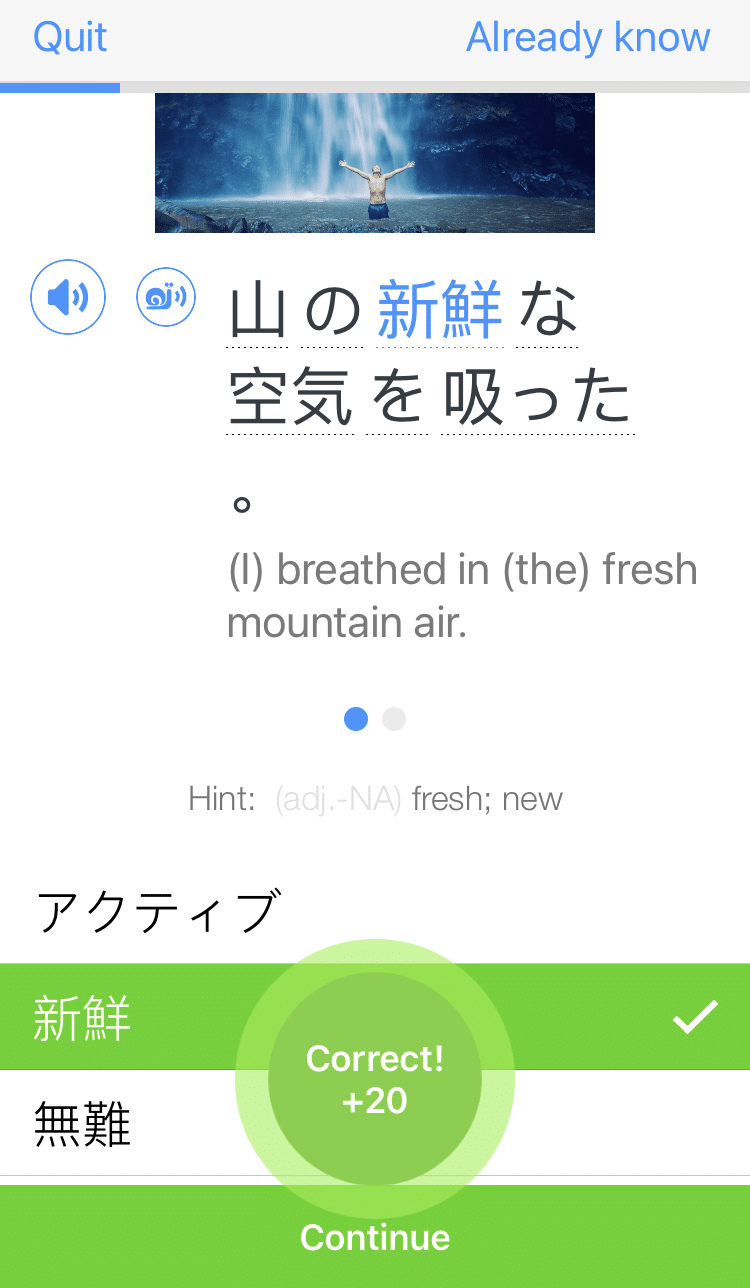

The best part? FluentU keeps track of your vocabulary, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You'll have a 100% personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Enter your e-mail address to get your free PDF!

We hate SPAM and promise to keep your email address safe

Government-approved information site

Japan creates the future.

The future is what you create.

For prospective students

Search for schools

Search for schools by major, campus location, language of instruction, or other areas of interest.

Search for scholarships

Search for scholarships offered by schools, local governments, international exchange organizations, and private entities, as well as for tuition reductions and exemption programs offered independently by schools.

Useful information

Japanese Educational System

Universities (Undergraduate) and Junior Colleges

Graduate Schools

Japanese Language Institutes

Scholarships

Living Costs and Expenses

Part-Time Work

Employment in Japan

For Students

Prospective students

Current students

Support Measures for Ukrainian Students by Japanese Universities and Japanese Language Institutes

Announcement of Study in Japan official website renewal

Events for the people who want to work as Specified Skilled Worker (Immigration Services Agency of Japan)

Cool Japan Photo Contest for Foreigners 2023

JAPAN-UKRAINE UNIVERSITY PATHWAYS 2024 (external link)

JAPAN CAREER PROMOTION FORUM Central Eastern Europe 2023 (9/15)

Reasons to Choose Japan

The cultural heritage of mt. fuji, japanese cuisine, and much more; the spirit of omotenashi (hospitality).

Japan’s rich natural environments, from mountain forests to beaches and coastlines, offer all-new sights with the coming of each season. The country consists of eight major regions that each have their own distinct culture, traditions, and natural scenery. When selecting where you want to study in Japan, it would also be interesting to know about the regional uniqueness of each school’s location.

We use cookies to provide you with better services on our website. Please clink on "Agree" to agree and proceed. For more information and cookie settings, please click on “See Details”.

See Details

Study and Research Opportunities in Japan

Featured opportunities in japan.

The long and short-term academic programs are available in Japan across many universities and educational centers. International students and researchers may apply to BA, MA, Ph.D., and postdoctoral research programs in Japan. Moreover, summer schools and conferences are excellent academic activities that make Japan an attractive destination for scholars and scientists. Many programs also come with fully-funded scholarships and fellowships, as well as travel grants and financial aid. Thus every student, researcher, and professor can always find a suitable program in Japan and apply.

Scholarship Opportunities

- Young Leaders’ Program, Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan

- Scholarships for Ph.D. in Sustainable Science, JFUNU

- Ting Hsin Scholarship at Waseda University

- Scholarship for International Students, Kochi University

- Japan-International Monetary Fund Scholarship

- Japan Human Resource Development Scholarships for Asian Developing Countries

- Monbukagakusho Honors Scholarship for Privately-Financed International Students

- The Joint Japan/World Bank Graduate Scholarship Program

- The Kyoto University of Advanced Science, Undergraduate scholarship

- GIGA scholarships for undergraduate students, Keio University

- DOCOMO International Student Scholarship

- Sato Yo International Scholarships for Students in developing countries

- Japan-WCO Human Resource development program

- Non-Japanese Graduate Scholarship for Women

Fellowships

- Rotary-Peace Fellowships

- Canon Foundation research fellowships

- Ishibashi Foundation/The Japan Foundation Fellowship for Research on Japanese Art

- UNESCO/KEIZO Obuchi Research Fellowship Program

- CSEAS Postdoctoral Fellowship

- Japan JSPS Bridge Research Fellowship

- Visiting research fellowship Kokugakuin University

- The Matsumae International Fellowship program

- International Affairs Fellowship in Japan

- Abe Fellowships in Journalism

- Daiohs Memorial Foundation Scholarships for International Students

- MetCenter Grant Programs

- Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research in Kakenhi

- Toyota Foundation International Grant Program

- Toshiba Foundation Grants

- Japan International Cooperation Agency Grants

- The Japan Foundation ASIA Center Grants & Fellowships

- The Japan Foundation Center for Global Partnership Grant Program

- The Japan Social Development Fund Grants

Summer programs

- Okayama University Summer Program

- Kumamoto University Summer Programs

- Hokkaido JaLS Summer Program

- KCP International Summer Language school

- World Campus International Summer Programs in Japan

- Meiji University Japanese language summer program

- EF International Language Campuses

- KIIS 2 weeks in Japan program

- IBS Virtual Japanese Summer

- Teenage Japanese Courses Abroad, CESA Language abroad

What does it feel like to be an international student in Japan?

Japan is willing to welcome international students to their national universities. In 2003, 100,000 international students were studying in Japan, and the government set the target to increase this number to 300.000.

There are adopted policies and strategies to promote the academic goodwill of the country for international students. For example, there are many course schemes taught partially or entirely in English. Also, many universities hire specific staff whose responsibility is to assist international students.

Another significant aspect of convenience is that Japan organizes many exchange programs. Also, instead of the standard Japanese academic year, which starts in April, international students can start their studies from September , as accustomed in many foreign countries.

You might have already explored from the above links that the Japanese government broadly supports international students by covering not only study expenses but also living and other related ones.

What do you need to enter a Japanese university?

The entry requirements differ per university and per program you apply to study in Japan. However, the typical approach of 95% of national universities and 65% of public universities requires EJU, which stands for Examination for Japanese University for international students for undergraduate studies.

Be sure to carefully check the entry requirements, as some universities may require you to take an additional test other than EJU. The cost of those tests may vary near US$67-$125 and is offered twice a year.

EJU is a standard test for assessing the students' basic academic abilities in science, math, and "Japan and the world." You may feel disappointed at this point, as exams are additional stress at the end. However, from another perspective, this test is a second chance to succeed in your academic career, even if your GPA is not high.

In the case of Master's and Ph.D. programs, entry requirements are set by each university. Usually, they are assessments of academic abilities or previous academic progress. For graduate program applications, you will be required to submit a CV, research proposal, statement of purpose, recommendations, previous awards, etc.

In both study levels, you might be required to pass TOEFL or IELTS if the course is taught in English, and the Japanese-language proficiency test , if the course is in Japanese.

Japan Universities

You have around 780 university options in Japan, the majority of which are private. The nation's strongest Universities are considered to be the University of Tokyo ( 24th in the QS World University Rankings 2021), Kyoto University (38th), and Tokyo Institute of Technology (56th).

In addition to the mentioned ones, Japan has 38 universities ranked in the global university rankings for the current year. Filter the rankings by country-Japan to receive the whole list of the best Japanese universities.

The oldest university of Japan is considered Komazawa University, founded in 1592 in the Tokyo Metropolis urban area. The 428-year-old Komazawa University exists up to current. It offers bachelor's, master's, and doctorate degrees in numerous study areas.