An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Effects of nurse-to-patient ratio legislation on nurse staffing and patient mortality, readmissions, and length of stay: a prospective study in a panel of hospitals

Matthew d mchugh.

a School of Nursing, Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Linda H Aiken

Douglas m sloane, carol windsor.

b School of Nursing, Queensland University of Technology, Kelvin Grove, QLD, Australia

c Centre for Healthcare Transformation, Faculty of Health, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Clint Douglas

d Metro North Hospital and Health Service, Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital, Herston, QLD, Australia

Patsy Yates

Associated data.

The nurse survey data cannot be shared in any form as a condition of survey respondent consent. The patient data cannot be shared by the investigators under the data use agreement with Queensland Health; however, the original admitted patient data collection can be requested directly from Queensland Health.

Substantial evidence indicates that patient outcomes are more favourable in hospitals with better nurse staffing. One policy designed to achieve better staffing is minimum nurse-to-patient ratio mandates, but such policies have rarely been implemented or evaluated. In 2016, Queensland (Australia) implemented minimum nurse-to-patient ratios in selected hospitals. We aimed to assess the effects of this policy on staffing levels and patient outcomes and whether both were associated.

For this prospective panel study, we compared Queensland hospitals subject to the ratio policy (27 intervention hospitals) and those that discharged similar patients but were not subject to ratios (28 comparison hospitals) at two timepoints: before implementation of ratios (baseline) and 2 years after implementation (post-implementation). We used standardised Queensland Hospital Admitted Patient Data, linked with death records, to obtain data on patient characteristics and outcomes (30-day mortality, 7-day readmissions, and length of stay [LOS]) for medical-surgical patients and survey data from 17 010 medical-surgical nurses in the study hospitals before and after policy implementation. Survey data from nurses were used to measure nurse staffing and, after linking with standardised patient data, to estimate the differential change in outcomes between patients in intervention and comparison hospitals, and determine whether nurse staffing changes were related to it.

We included 231 902 patients (142 986 in intervention hospitals and 88 916 in comparison hospitals) assessed at baseline (2016) and 257 253 patients (160 167 in intervention hospitals and 97 086 in comparison hospitals) assessed in the post-implementation period (2018). After implementation, mortality rates were not significantly higher than at baseline in comparison hospitals (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 1·07, 95% CI 0·97–1·17, p=0·18), but were significantly lower than at baseline in intervention hospitals (0·89, 0·84–0·95, p=0·0003). From baseline to post-implementation, readmissions increased in comparison hospitals (1·06, 1·01–1·12, p=0·015), but not in intervention hospitals (1·00, 0·95–1·04, p=0·92). Although LOS decreased in both groups post-implementation, the reduction was more pronounced in intervention hospitals than in comparison hospitals (adjusted incident rate ratio [IRR] 0·95, 95% CI 0·92–0·99, p=0·010). Staffing changed in hospitals from baseline to post-implementation: of the 36 hospitals with reliable staffing measures, 30 (83%) had more than 4·5 patients per nurse at baseline, with the number decreasing to 21 (58%) post-implementation. The majority of change was at intervention hospitals, and staffing improvements by one patient per nurse produced reductions in mortality (OR 0·93, 95% CI 0·86–0·99, p=0·045), readmissions (0·93, 0·89–0·97, p<0·0001), and LOS (IRR 0·97, 0·94–0·99, p=0·035). In addition to producing better outcomes, the costs avoided due to fewer readmissions and shorter LOS were more than twice the cost of the additional nurse staffing.

Interpretation

Minimum nurse-to-patient ratio policies are a feasible approach to improve nurse staffing and patient outcomes with good return on investment.

Queensland Health, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research.

Introduction

The years 2020–21 have been designated by WHO as the International Year of the Nurse and Midwife to honour the 200th anniversary of Florence Nightingale's birth. 1 Nightingale, through meticulous records and application of innovative statistics, documented that more British soldiers in military hospitals during the Crimean War died because of unsafe hospital conditions than of wounds in battle. Her solution was the introduction of trained nurses, shown by her research to be associated with reduced hospital deaths. Nurses are still saving lives in modern hospitals, and research suggests that patient harm can be further reduced by investments in nurse staffing.

The Lancet published in 2014 a landmark study showing that patients' risk of dying after surgery varied by the number of patients for whom each nurse had responsibility. 2 Studying outcomes of nearly half a million patients in nine European countries, investigators found that each additional patient added to nurses' average workloads was associated with 7% higher odds of a patient dying within 30 days of admission. Evidence continues to grow that better hospital nurse staffing is associated with better patient outcomes, including fewer hospital acquired infections, shorter length of stay (LOS), fewer readmissions, higher patient satisfaction, and lower nurse burnout. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 Yet, substantial within-country variation in hospital nurse staffing persists, giving rise to calls for public policy interventions to establish minimum safe staffing standards in hospitals. In 2018, the International Council of Nurses, representing national nursing associations worldwide, issued their Position Statement on Evidence-Based Nurse Staffing, concluding that plenty of evidence supports taking action now to improve hospital nurse staffing, echoing Nightingale's call to action over 150 years ago, that if we have evidence and fail to act, we are going backwards. 15

Research in context

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed for original research articles published in English between Jan 1, 1985, and March 1, 2020, with the following search terms (separately and in combination): “nursing”, “staffing”, “nurse-to-patient ratios”, and “staffing mandate”. We also did a manual search based on bibliographies of relevant papers. In 2014, The Lancet published the largest international study on the subject, involving hundreds of thousands of patients in 300 hospitals across nine countries, showing that patients in hospitals with better nurse staffing levels were less likely to die in hospital than those being treated in poorly staffed hospitals. This study capped decades of research linking staffing levels to outcomes including mortality, readmissions, length of stay, adverse events, and patient satisfaction. Most research, however, has been cross-sectional; the few longitudinal studies have been done in single or a small number of hospitals. The small number of evaluations of implemented policy were retrospective and relied upon administrative staffing data known to overestimate staffing levels by including nurses who are not in patient care roles (eg, managers).

Added value of this study

Despite being frequently debated, policy tools to achieve safe nurse staffing levels have rarely been implemented—only a few jurisdictions have done so over the past 30 years. In the places that implemented such policies, no prospective evaluations linked with patient outcomes have been done. The absence of such an evaluation has been cited as a reason why similar policies have not been adopted elsewhere. In 2016, Queensland, Australia, implemented a policy establishing minimum nurse-to-patient ratios in medical-surgical wards in 27 public hospitals that care for 83% of patients hospitalised across the state. We report the findings of a first-of-its-kind prospective evaluation of Queensland's policy. In addition to evaluating the effect of the policy on mortality, we examined outcomes with cost implications (ie, readmissions and length of stay) relevant to financial considerations of health ministers and hospital administrators. The findings can directly inform debates in jurisdictions considering similar policies.

Implications of all the available evidence

These results support decades of research that suggested that making changes to improve staffing levels could result in better outcomes. Policy interventions establishing minimum nurse-to-patient ratios are feasible and yield significantly better outcomes for patients and a better return on investment to the public.

The first jurisdictions to implement minimum nurse-to-patient ratios policies were the states of Victoria, Australia, and California, USA, in the late 1990s. 16 , 17 The past 5 years have seen a resurgence of interest in establishing minimum nurse-to-patient ratio policies—Wales and Scotland (UK), Ireland, and Queensland (Australia) have implemented such policies 18 and multiple US states are considering them. 19 Queensland's legislation is noteworthy because an independent prospective evaluation was included. Here, we report the results of that evaluation.

On July 1, 2016, Queensland established minimum nurse-to-patient ratios (the term nurse includes registered and enrolled nurses [nurses with a technical diploma who work under the supervision of a registered nurse]) for adult medical-surgical wards in 27 public hospitals. The legislation required that average nurse-to-patient ratios on morning and afternoon shifts be no lower than 1:4 and on night shifts no lower than 1:7. We collected survey data at the hospital level from thousands of nurses to link with data on patients' clinical characteristics and outcomes from the period before and 2 years after implementation of ratios. Relative to comparison hospitals, we evaluated whether greater staffing improvements occurred at intervention hospitals, whether outcomes improved more at intervention hospitals, and whether the staffing improvements explained, at least partly, any advantage on patient outcomes.

Study design

This prospective panel study (RN4CAST-Australia) was quasi-experimental: we compared changes in measures of outcomes in a prospective panel of hospitals where assignment of the hospital to the treatment condition (the policy intervention) was non-random. We used nurse-reported data to measure medical-surgical nurse staffing levels and standardised patient data to measure outcomes at two timepoints: before implementation of ratios (baseline) and 2 years after implementation (post-implementation). We restricted our staffing measure to medical-surgical staffing and to nurses providing direct patient care. We compared two groups of hospitals: hospitals subject to the policy (intervention hospitals) and hospitals that discharged similar patients but were not subject to ratios (comparison hospitals). Intervention hospitals were chosen by the government to represent regions across the state. Therefore, our study accounted for pre-existing differences between intervention and comparison hospitals through statistical controls, including controls for hospital size and patient's characteristics. We aimed to answer three main questions: first, whether changes in nurse staffing levels were different between intervention and comparison hospitals; second, whether changes in patient outcomes were different between intervention and comparison hospitals; and third, whether the staffing changes were associated with differential patient outcomes after accounting for differences in patient and hospital characteristics.

Ethics approval was obtained from the Queensland University of Technology (Kelvin Grove, QLD, Australia) and the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, PA, USA). Use of the deidentified Queensland Hospital Admitted Patient Data Collection and linked death registry data was approved by Queensland Health in accordance with the Public Health Act 2005.

Study population and data sources

We used the standardised Queensland Hospital Admitted Patient Data Collection from the baseline period (July 1, 2015, to June 1, 2016) and 2 years after implementation of ratios (Jan 1 to Dec 31, 2018). The datafiles provide detailed information on patient demographics, diagnoses, procedures (with coding from the International Classification of Diseases, tenth edition, Australia modification), comorbidities, and discharge status. The files were linked with death records to measure 30-day mortality. Our focus was on adult patients in general medical-surgical wards—the clinical area targeted for change in nurse staffing ratios. Patients undergoing labour and delivery and patients being treated for psychiatric conditions were excluded.

We surveyed registered nurses and enrolled nurses—the types of nurses considered under the policy—before and after policy implementation to gather information on medical-surgical nurse staffing levels in the hospitals where they worked. Surveying bedside nurses, an approach supported by the organisational research literature, 20 yields data on staffing levels with excellent predictive validity 2 , 4 compared with single key-informant reports or administrative data, which often include non-direct care nurses (eg, management) and inflate staffing estimates. We provided respondents with a list of Queensland hospitals, so nurses could identify their hospital and the type of ward where they worked. This allowed us to attribute information from medical-surgical ward respondents to their hospital, aggregate their responses to produce hospital-level measures of medical-surgical ward staffing, and link them to independent data on patient outcomes and hospital size. The baseline survey data were collected between May 1 and May 31, 2016 (before ratio implementation on July 1, 2016). We repeated the survey 2 years after implementation between May 1 and May 31, 2018. We used a modified Dillman 21 approach for email survey campaigns. In the baseline period, we sent emails and reminders to 26 871 nurses and received responses from 8732, giving an overall response rate of 32%. 2 years after implementation, we sent 30 658 emails and received responses from 8278 nurses, giving a response rate of 27%. Although a downward trend in survey responses has been well known in the past decade, these response rates were satisfactory and considered high for email-based surveys. 22 , 23 These rates are consistent with or better than response rates for similar nurse surveys in the USA. 3 , 4 , 24 , 25 The most important issue for the design of this study was to have a sufficient number of responses from nurses in each hospital to provide reliable staffing estimates. Although no threshold has been set for the number of respondents that ensures the reliability of the staffing measure we estimate, our previous work suggests that ten or more nurses per hospital suffice to provide staffing estimates that differ little from, and have the same effect as, measures estimated from 20, 30, or 40 or more nurses. 2 , 3 , 4 The average number of medical-surgical nurse respondents per hospital was sufficient for the purposes of this study—our sample of hospitals (55, with 27 intervention hospitals and 28 comparison hospitals) included almost all hospitals in Queensland with more than 100 beds, represented by an average of 64 nurse respondents per hospital and as many as 588. Of key importance from the standpoint of representativeness, the 36 hospitals in our analyses accounted for 83% of all adult patient admissions to acute care hospitals statewide. Although nurse staffing on every ward probably affects patient outcomes, we restricted our attention to medical-surgical wards because doing so simplified the comparison across intervention and comparison hospitals, and these wards were the targeted setting for the policy.

Our measure of primary interest was hospital-level nurse-to-patient ratio on adult medical-surgical wards (hereafter referred to as nurse-to-patient ratios). By asking each nurse how many nurses and patients were on the ward during the last shift the nurse worked, and by averaging them to ward level and then hospital level, we produced a nurse staffing measure reflecting the average nurse-to-patient ratio across all medical-surgical wards in the hospitals. This method is consistent with the ratios legislation, which allows individual nurses to have a greater (or lesser) number of patients than the prescribed ratio, so long as the ward's average is in compliance during the shift. As in other work, 2 , 4 we expressed the ratio as the number of patients per nurse, allowing us to interpret model results in terms of the effect of each additional patient per nurse on each outcome.

Patient outcomes we assessed were patient 30-day mortality, 7-day readmission, and LOS. We used the Queensland Hospital Admitted Patient Data files to identify patient outcomes. These data were linked with death records, allowing us to capture deaths occurring within 30 days of admission, even those occurring outside the hospital. This eliminated bias due to hospital LOS variation arising from different discharge practices. 26 To measure 7-day readmissions, we established the initial admission for each patient during each time period as the index admission. Patients who died during the index admission were excluded. For each index admission, we created a binary variable coded 0 if the patient was not admitted to any acute care hospital in the 7 days after discharge from index hospitalisation, and 1 if the patient was admitted within 7 days of discharge (except obstetric deliveries). LOS was measured continuously from admission to discharge. The minimum LOS was 1 day. Same-day and long-term (LOS >30 days) patients were excluded.

To adjust for differences in patient mix across hospitals, our readmission and mortality models included risk scores for each outcome derived from models that regressed the different outcomes on 17 indicators (eg, diabetes, cancer, and so on) from the Charlson Comorbidity Index to account for confounding comorbidities, 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 as well as sex, age, and dummy variables for the Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG). These scores were derived from separate logistic regression models in which we estimated a risk score for death or readmission based on the patient characteristics described. These models showed excellent discrimination ( c statistics were approximately 0·90). Readmission models were restricted to short-term patients (LOS ≤30 days) with discharge to home. Models for LOS were also restricted to short-term patients and controlled for whether patients died during hospitalisation and for age, mortality risk, comorbidities, and DRG.

Statistical analysis

We first described the patients in intervention and comparison hospitals before and after implementation of ratios, including their sex, age, comorbidities, and outcomes (ie, mortality, readmissions, and LOS). We then provided the results of estimating multilevel random-intercept logistic regression models for mortality and readmissions and zero-truncated negative binomial regression models (LOS was a count variable) to produce odds ratios (ORs) for mortality and readmissions and incident rate ratios (IRRs) for LOS, indicating the differential change in outcomes between patients in intervention and comparison hospitals, after accounting for hospital characteristics (ie, size and time-invariant factors) and patient characteristics. The specification of multilevel models for panels of macro units with observations on nested micro units is detailed in Fairbrother, 31 and its elaboration in the context of a prospective panel study of nurses nested within hospitals is presented in Sloane and colleagues. 24 Finally, after showing how nurse staffing had changed over time, we used similar models to estimate whether staffing improvements were associated with patient outcome improvements. We did not have missing data; all models were adjusted for clustering of patients in hospitals and controlled for hospital size. Using expected frequencies derived from our models, we estimated the counterfactual for each outcome, that is, what outcomes would we expect in intervention hospitals if ratios had not been implemented. We then used published cost data to make a rough estimate of return on investment derived by preventing additional LOS and readmissions.

Role of the funding source

The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

For this study, we included 231 902 patients (142 986 in intervention hospitals and 88 916 in comparison hospitals) assessed at baseline (2016) and 257 253 patients (160 167 in intervention hospitals and 97 086 in comparison hospitals) assessed in the post-implementation period (2018). Patients in intervention hospitals were slightly younger and less likely to be women than those in comparison hospitals ( table 1 ). The differences in comorbidities between timepoints were minimal in most cases for patients in both intervention and comparison hospitals. Although slightly higher rates of diabetes without complications and cancer were observed in patients in comparison hospitals, all other comorbidities were somewhat more common in patients in intervention hospitals.

Patient characteristics by baseline or post-implementation time period and by intervention or comparison hospitals

Data are n (%) or mean (SD). Comorbidities present for fewer than 1% of patients are included in the analyses but excluded from this table. These include peripheral vascular disease, rheumatoid disease, peptic ulcer disease, moderate or severe liver disease, and AIDS.

Regarding the average number of patients per nurse, comparison hospitals averaged 6·13 patients per nurse (SD 0·75) at baseline and improved slightly after implementation to 5·96 patients per nurse (0·98). Intervention hospitals were better staffed on average at baseline (4·84 patients per nurse, SD 1·05) but improved by a greater margin to 4·37 patients per nurse (0·54) after implementation ( table 2 ). The differences in these SDs, while unadjusted, indicate that the variation across intervention hospitals was reduced by half, whereas the variation across comparison hospitals increased somewhat over time. Regarding patient outcomes, 30-day mortality was somewhat higher overall at each timepoint for patients in intervention hospitals than for those in comparison hospitals, but although the percentage of patient deaths increased over time for patients in comparison hospitals, it decreased for those in intervention hospitals ( table 2 ). Readmissions were slightly higher overall and in each timepoint for patients in intervention hospitals than for those in comparison hospitals, though the only change that occurred across timepoints—to the extent there was any change at all—was restricted to patients in comparison hospitals. Fewer than 2·8% of these patients were readmitted at baseline, whereas nearly 3% were readmitted post-implementation ( table 2 ). By contrast, mean LOS was shorter and declined by a greater amount for patients in intervention hospitals than for those in comparison hospitals.

Patient mortality, readmissions, and length of stay, by timepoint and by intervention or comparison hospitals

Data are n/N (%), unless otherwise specified.

These results are tentative because they were not adjusted for differences in patient characteristics (eg, sex, age, and comorbidities) or differences in the size of intervention and comparison hospitals. To make these adjustments and assess differences across the two hospital groups over time, we used multilevel and multivariable models and, in the case of mortality and readmissions, converted percentages and percentage differences to odds and ORs. We first used the full sample of 55 hospitals to address whether the changes in outcomes were different in intervention versus comparison hospitals. We then used the sample of 36 hospitals with staffing data available to address whether, and to what extent, change in the outcomes in the two hospital groups were due to changes in staffing.

At baseline, patients in intervention hospitals had 34% higher 30-day mortality odds than those in comparison hospitals (adjusted OR 1·34, 95% CI 1·09–1·64, p=0·0052; table 3 ). After implementation, patients in comparison hospitals had higher, though not significantly, 30-day mortality odds (1·07, 0·97–1·17, p=0·18) than at baseline, whereas patients in intervention hospitals had significantly lower odds (0·89, 0·84–0·95, p=0·0003) than at baseline. The adjusted OR for the interaction between intervention hospitals and the implementation timepoint (0·84, 0·75–0·93, p=0·0016) implied that the difference in 30-day mortality odds between patients in intervention and comparison hospitals in the post-implementation period was significantly smaller than at baseline—only 12% higher (1·12, 0·91–1·37, p=0·28) and no longer significant ( vs the significant difference of 34% higher at baseline).

Adjusted ORs and IRRs indicating the differences in mortality, readmissions, and length of stay between intervention and comparison hospitals (total n=55) and differential changes in those outcomes across timepoints

ORs for 30-day mortality and 7-day readmissions were estimated with random-intercept logistic regression models. IRRs for length of stay were estimated with zero-truncated negative binomial regression models. All models adjusted for the clustering of patients in hospitals and controlled for hospital size. DRG=Diagnosis-Related Group. IRR=incident rate ratio. OR=odds ratio.

The main ORs and interaction effects for readmissions and IRRs for LOS showed a similar pattern ( table 3 ). Patients in intervention hospitals initially had 15% higher odds on readmissions than those in comparison hospitals (adjusted OR 1·15, 0·98–1·34, p=0·090), and patients in comparison hospitals had a 6% increase in odds of readmission from baseline to post-implementation (1·06, 1·01–1·12, p=0·015). At the same time, no change over time was observed for patients in intervention hospitals (1·00, 0·95–1·04, p=0·92). The adjusted OR for the interaction (0·94, 0·88–0·99, p=0·049) implied that the difference in odds of readmission between patients in intervention and comparison hospitals in the post-implementation period was significantly smaller than at baseline—only 8% higher (1·08, 0·92–1·26, p=0·35) and no longer indicating a significant difference. Patients in intervention hospitals initially had 22% shorter LOS than those in comparison hospitals (adjusted IRR 0·78, 95% CI 0·72–0·84, p<0·0001). For patients in comparison hospitals, we observed a decrease in the average LOS by a factor of 0·95 (0·93–0·98, p=0·0001), or 5%. For patients in intervention hospitals, the decrease in LOS was even greater and equal to 0·91 (95% CI 0·89–0·94, p<0·0001), or by 9%. The adjusted OR for the interaction (0·95, 0·92–0·99, p=0·010) suggests that the difference in LOS between patients in intervention and those in comparison hospitals in the post-implementation period was even greater than at baseline—26% shorter LOS (0·74, 0·68–0·81, p<0·0001).

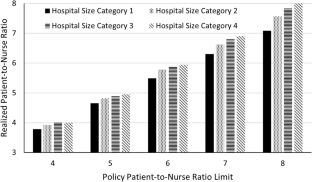

Subsequently, we focused on whether outcomes changes resulted from changes in staffing specifically. We eliminated the interaction between intervention and timepoint considered in the previous analyses and replaced it with an indicator of the staffing change over time and the effect on outcomes. The 36 hospitals for which we had reliable staffing measures included 21 (78%) of 27 intervention hospitals and 15 (54%) of 28 comparison hospitals. Staffing changed from baseline to post-implementation in these 36 hospitals ( figure ). 30 (83%) hospitals had staffing that amounted to more than 4·5 patients per nurse at baseline, whereas the same was true for only 21 (58%) hospitals in the post-implementation period. Notably, only one comparison hospital had a marked decrease in the ratio of patients per nurse between timepoints (ie, from one ratio interval to a lower one in the figure ) and, although average patients per nurse diminished by 0·47 in intervention hospitals, it diminished by 0·17 patients per nurse in comparison hospitals.

Number of hospitals with various staffing levels at baseline and post-implementation

When staffing and changes in staffing were taken into account, the difference between intervention and comparison hospitals—the intervention effect—was significant only for LOS, while the overall change—the post-implementation effect—in readmissions and LOS remained significant ( table 4 ). Most notably, the model showed that when staffing improves, or decreases by one patient per nurse, the odds on all three outcomes decrease significantly ( table 4 ).

Adjusted ORs and IRRs indicating the differences in mortality, readmissions, and length of stay between intervention and comparison hospitals and the effect of changes in staffing on those outcomes across timepoints

DRG=Diagnosis-Related Group. IRR=Incident rate ratio. OR=odds ratio.

Using the expected frequencies derived from our models, we estimated that, absent the policy, intervention hospitals could have expected to see 145 more deaths, 255 more readmissions, and 29 222 additional hospital days. It was estimated that 167 full-time equivalents were needed to meet ratio requirements (Mohle B, Queensland Nurses and Midwives' Union, personal communication); at an average cost of AUD$100 000 (on the high end of the wage range) per full-time equivalent per year, 32 the cost to fund these positions would amount to approximately $33 000 000 over the first 2 years post-implementation. Taking our estimates of LOS days and readmissions averted, we can estimate avoided costs. We used data from Australia's Independent Hospital Pricing Authority 33 on average hospital day costs in Queensland ($2312 in 2015–16) as the basis of our estimates. By preventing 255 readmissions with an average LOS of 2·7 days, the average costs avoided would be $1 589 594 (95% CI 1 179 120–2 358 240). By preventing 29 222 hospital days, the average costs avoided would be $67 561 264 (54 049 011–81 073 517).

Our prospective panel study of Queensland hospitals revealed four key findings. First, the nurse-to-patient ratios mandate resulted in nurse staffing improvements at intervention hospitals that were significantly different from those in comparison hospitals, where staffing remained largely unchanged. This suggests that the improvements we observed were not part of a statewide secular trend of better nurse staffing; rather, the change was largely isolated to the hospitals prompted to improve by the policy. Second, intervention hospitals saw greater patient outcome improvements. Although intervention hospitals had patients who were sicker than those in comparison hospitals, and thus had somewhat worse baseline outcomes, their improvement in mortality, LOS, and readmissions was significantly better even after accounting for demographics, comorbidities, DRGs, and hospital size. Third, using data from medical-surgical ward nurses (the setting targeted by the policy), we found that changes in staffing in intervention hospitals accounted for a significant share of the outcome advantage for those hospitals. Finally, our estimates suggest that the policy resulted in significant cost savings.

This study also contributes to the understanding of the causal relationship between improved staffing and patient outcomes. The literature showing better outcomes in better staffed hospitals mostly involves cross-sectional studies; although they highlight clear associations, causality cannot necessarily be inferred. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 Some studies have examined longitudinal data and have determined that outcomes improve more when staffing similarly improves, 23 but these studies relied on natural staffing change trends. Our study takes the additional step of informing whether direct state intervention yields better staffing, and whether those staffing improvements result in better patient outcomes. The answer to both questions was yes. Although probably not the only policy design that could stimulate staffing improvements and improved outcomes, Queensland's policy implementation is a viable model offering lessons for other countries.

Our study has limitations. We refer to it as a quasi-experimental study, which is appropriate in the broad sense that it involves comparing a sample of comparison hospitals with intervention hospitals before and after the intervention—in this case an improvement in staffing—is observed in one group but not the other and in a natural setting rather than a controlled environment. However, the participating hospitals were not selected at random and were not assigned randomly to intervention and comparison groups—rather, intervention hospitals were chosen by the government. Moreover, comparison hospitals were not matched to intervention hospitals because we did not have the information needed for matching on many relevant characteristics and because the number of potential matches was insufficient for a very complete matching in any event. Therefore, we had to control for differences between hospitals using statistical controls rather than by design, or by using randomly selected and assigned hospitals. The higher prevalence of pre-existing conditions among patients in the intervention hospitals might have been due to the fact that intervention hospitals were larger (all comparison hospitals had fewer than 500 beds, whereas 22 [81%] of 27 intervention hospitals had fewer than 500 beds and five [19%] had more than 500 beds). However, our incorporation of patient-level measures of pre-existing conditions did adjust for a key observable factor that differentiated intervention from comparison hospitals, and the prospective panel design, with a focus on change over time, eliminated unobserved fixed effects that might have distinguished the two hospital groups. An additional limiting factor is that there were not enough medical-surgical nurses in some hospitals to reliably estimate the average staffing on medical-surgical wards, especially in small comparison hospitals. Nonetheless, most relevant patients were covered by the study hospital panel, suggesting that a nurse-to-patient ratio mandate would have a substantial public benefit.

The costs saved because of reduced LOS and readmissions were estimated to be more than twice the costs of the additional staffing needed to comply with the policy while also yielding lower mortality. This information on Queensland offers insights for the jurisdictions that are debating minimum nurse-to-patient ratio policies (eg, New York and Illinois in the USA, and others in Australia) and for the international interest in interventions to improve nurse staffing. The most recent debate over nurse-to-patient ratios was in 2017, in Massachusetts (USA), which proposed a ratios mandate by ballot initiative. 34 The state was flooded with advertising from interested stakeholders against ratios, arguing that the evidence for ratios was insufficient. Opponents raised concerns that there had not been a prospective evaluation of a staffing policy such as the one described in this report, and thus evidence of effectiveness was unclear. Likewise, opponents argued that little information existed about the return on investment from the additional nurses required as a result of a ratios mandate. Our findings fill these gaps.

An argument raised when California implemented ratios was that the policy was inflexible, applying ratios to all nurses at all times—when a nurse needed to go to lunch or take a break, other nurses were needed to cover the patient assignment. But other nurses were often at their limit and couldn't take additional patients, even for a short period, and still comply with the law. This frustrated managers and made implementation difficult for many hospitals, especially early on. By contrast, Queensland mandated a minimum average staffing level at the ward level—an individual nurse could have more or fewer so long as the average number of patients per nurse didn't exceed the ratio limits. This offered more flexibility in patient assignments. Our analysis suggests that Queensland's flexible design is feasible and yields good outcomes. The Queensland evaluation design has prompted similar policy research in the USA, with similar findings. 35 , 36

In conclusion, having enough nurses with manageable workloads has been shown to be important for good patient care and outcomes. The 2018 International Council of Nurses' Position Statement on Evidence-Based Nurse Staffing 16 recommends that governments should take action to ensure safe staffing levels. The results presented here suggest that minimum nurse-to-patient ratio policies are a feasible instrument to improve nurse staffing, produce better patient outcomes, and yield a good return on investment.

Data sharing

Declaration of interests.

We declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from Queensland Health and the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research (R01NR014855). The authors are independent and solely responsible for study design, data collection and analysis, findings, and interpretation, which do not necessarily represent views of Queensland Health. We would like to acknowledge Tim Cheney, Frances Hughes, Irene Hung, Beth Mohle, Shelley Nowlan, Natalie Spearing, and Kate Veach for their contributions to this work.

Contributors

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. MDM, LHA, CW, CD, and PY contributed to the collection of data. MDM and DMS accessed, verified, and oversaw analysis of the data. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data and preparation of the manuscript. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Effects of nurse-to-patient ratio legislation on nurse staffing and patient mortality, readmissions, and length of stay: a prospective study in a panel of hospitals

Affiliations.

- 1 School of Nursing, Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 School of Nursing, Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

- 3 School of Nursing, Queensland University of Technology, Kelvin Grove, QLD, Australia; Centre for Healthcare Transformation, Faculty of Health, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia.

- 4 School of Nursing, Queensland University of Technology, Kelvin Grove, QLD, Australia; Centre for Healthcare Transformation, Faculty of Health, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia; Metro North Hospital and Health Service, Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital, Herston, QLD, Australia.

- PMID: 33989553

- PMCID: PMC8408834

- DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00768-6

Background: Substantial evidence indicates that patient outcomes are more favourable in hospitals with better nurse staffing. One policy designed to achieve better staffing is minimum nurse-to-patient ratio mandates, but such policies have rarely been implemented or evaluated. In 2016, Queensland (Australia) implemented minimum nurse-to-patient ratios in selected hospitals. We aimed to assess the effects of this policy on staffing levels and patient outcomes and whether both were associated.

Methods: For this prospective panel study, we compared Queensland hospitals subject to the ratio policy (27 intervention hospitals) and those that discharged similar patients but were not subject to ratios (28 comparison hospitals) at two timepoints: before implementation of ratios (baseline) and 2 years after implementation (post-implementation). We used standardised Queensland Hospital Admitted Patient Data, linked with death records, to obtain data on patient characteristics and outcomes (30-day mortality, 7-day readmissions, and length of stay [LOS]) for medical-surgical patients and survey data from 17 010 medical-surgical nurses in the study hospitals before and after policy implementation. Survey data from nurses were used to measure nurse staffing and, after linking with standardised patient data, to estimate the differential change in outcomes between patients in intervention and comparison hospitals, and determine whether nurse staffing changes were related to it.

Findings: We included 231 902 patients (142 986 in intervention hospitals and 88 916 in comparison hospitals) assessed at baseline (2016) and 257 253 patients (160 167 in intervention hospitals and 97 086 in comparison hospitals) assessed in the post-implementation period (2018). After implementation, mortality rates were not significantly higher than at baseline in comparison hospitals (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 1·07, 95% CI 0·97-1·17, p=0·18), but were significantly lower than at baseline in intervention hospitals (0·89, 0·84-0·95, p=0·0003). From baseline to post-implementation, readmissions increased in comparison hospitals (1·06, 1·01-1·12, p=0·015), but not in intervention hospitals (1·00, 0·95-1·04, p=0·92). Although LOS decreased in both groups post-implementation, the reduction was more pronounced in intervention hospitals than in comparison hospitals (adjusted incident rate ratio [IRR] 0·95, 95% CI 0·92-0·99, p=0·010). Staffing changed in hospitals from baseline to post-implementation: of the 36 hospitals with reliable staffing measures, 30 (83%) had more than 4·5 patients per nurse at baseline, with the number decreasing to 21 (58%) post-implementation. The majority of change was at intervention hospitals, and staffing improvements by one patient per nurse produced reductions in mortality (OR 0·93, 95% CI 0·86-0·99, p=0·045), readmissions (0·93, 0·89-0·97, p<0·0001), and LOS (IRR 0·97, 0·94-0·99, p=0·035). In addition to producing better outcomes, the costs avoided due to fewer readmissions and shorter LOS were more than twice the cost of the additional nurse staffing.

Interpretation: Minimum nurse-to-patient ratio policies are a feasible approach to improve nurse staffing and patient outcomes with good return on investment.

Funding: Queensland Health, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research.

Copyright © 2021 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Multicenter Study

- Cause of Death

- Health Policy*

- Length of Stay / statistics & numerical data*

- Middle Aged

- Nursing Staff, Hospital / supply & distribution*

- Patient Readmission / statistics & numerical data*

- Personnel Staffing and Scheduling / statistics & numerical data*

- Prospective Studies

- Quality of Health Care / statistics & numerical data*

Grants and funding

- R01 NR014855/NR/NINR NIH HHS/United States

Patient-to-nurse ratios: Balancing quality, nurse turnover, and cost

- Published: 29 November 2023

- Volume 26 , pages 807–826, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- David D. Cho 1 ,

- Kurt M. Bretthauer 2 &

- Jan Schoenfelder 3 , 4

1359 Accesses

Explore all metrics

We consider the problem of setting appropriate patient-to-nurse ratios in a hospital, an issue that is both complex and widely debated. There has been only limited effort to take advantage of the extensive empirical results from the medical literature to help construct analytical decision models for developing upper limits on patient-to-nurse ratios that are more patient- and nurse-oriented. For example, empirical studies have shown that each additional patient assigned per nurse in a hospital is associated with increases in mortality rates, length-of-stay, and nurse burnout. Failure to consider these effects leads to disregarded potential cost savings resulting from providing higher quality of care and fewer nurse turnovers. Thus, we present a nurse staffing model that incorporates patient length-of-stay, nurse turnover, and costs related to patient-to-nurse ratios. We present results based on data collected from three participating hospitals, the American Hospital Association (AHA), and the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD). By incorporating patient and nurse outcomes, we show that lower patient-to-nurse ratios can potentially provide hospitals with financial benefits in addition to improving the quality of care. Furthermore, our results show that higher policy patient-to-nurse ratio upper limits may not be as harmful in smaller hospitals, but lower policy patient-to-nurse ratios may be necessary for larger hospitals. These results suggest that a “one ratio fits all” patient-to-nurse ratio is not optimal. A preferable policy would be to allow the ratio to be hospital-dependent.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Improving patient safety by optimizing the use of nursing human resources.

Christian M. Rochefort, David L. Buckeridge & Michal Abrahamowicz

Evaluating the Costs and Outcomes of Hospital Nursing Resources: a Matched Cohort Study of Patients with Common Medical Conditions

Karen B. Lasater, Matthew D. McHugh, … Jeffrey H. Silber

The Nurse Workforce

Data availability.

The AHA and OSHPD data are publicly available.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2016) Access and disparities in access to health care. Rockville, MD. https://archive.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqdr15/access.html . Accessed 15 Sept 2022

Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Lake ET, Cheney T (2008) Effects of hospital care environment on patient mortality and nurse outcomes. J Nurs Adm 38(5):223–229

Article Google Scholar

Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski J, Silber JH (2002) Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. J Am Med Assoc 288(16):1987–1993

Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Bruyneel L, Van den Heede K, Griffiths P, Busse R, Diomidous M, Kinnunen J, Kózka M, Lesaffre E, McHugh MD, Moreno-Casbas MT, Rafferty AM, Schwendimann R, Scott PA, Tishelman C, van Achterberg T, Sermeus W (2014) Nurse staffing and education and hospital mortality in nine European countries: A retrospective observational study. The Lancet 383(9931):1824–1830

Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Cimiotti JP, Clarke SP, Flynn L, Seago JA, Spetz J, Smith HL (2010) Implications of the California nurse staffing mandate for other states. Health Serv Res 45(4):904–921

Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Griffiths P, Rafferty AM, Bruyneel L, McHugh M, Maier CB, Moreno-Casbas T, Ball JE, Ausserhofer D, Sermeus W (2017) Nursing skill mix in European hospitals: cross-sectional study of the association with mortality, patient ratings, and quality of care. BMJ Qual Saf 26:559–568

Aiken LH, Sermeus W, Van den Heede K, Sloane DM, Busse R, McKee M, Bruyneel L, Rafferty AM, Griffiths P, Moreno-Casbas MT, Tishelman C, Scott A, Mrzostek T, Kinnunen J, Schwendimann R, Heinen M, Zikos D, Sjetne IS, Smith HL, Kutney-Lee A (2012) Patient safety, satisfaction, and quality of hospital care: Cross sectional surveys of nurses and patients in 12 countries in Europe and the United States. BMJ 344:e1717

Aiken LH, Xue Y, Clarke SP, Sloane DM (2007) Supplemental nurse staffing in hospitals and quality of care. J Nurs Adm 37(7–8):335–342

Ang BY, Lam SWS, Pasupathy Y, Ong MEH (2018) Nurse workforce scheduling in the emergency department: a sequential decision support system considering multiple objectives. J Nurs Manag 26(4):432–441

Bae SH, Mark B, Fried B (2010) Use of temporary nurses and nurse and patient safety outcomes in acute care hospital units. Health Care Manage Rev 35(4):333–344

Ball JE, Bruyneel L, Aiken LH, Sermeus W, Sloane DM, Rafferty AM, Lindqvist R, Tishelman C, Griffiths P (2018) Post-operative mortality, missed care and nurse staffing in nine countries: across-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud 78:10–15

Benzaid M, Lahrichi N, Rousseau LM (2020) Chemotherapy appointment scheduling and daily outpatient–nurse assignment. Health Care Manag Sci 23(1):34–50

Bond C., Raehl CL, Pitterle ME, Franke T (1999) Health care professional staffing, hospital characteristics, and hospital mortality rates. Pharmacother: J Human Pharmacol Drug Ther 19(2):130–138

Bretthauer KM, Heese HS, Pun H, Coe E (2011) Blocking in healthcare operations: A new heuristic and an application. Prod Oper Manag 20(3):375–391

Brooks Carthon JM, Hatfield L, Brom H, Houton M, Kelly-Hellyer E, Schlak A, Aiken LH (2021) System-level improvements in work environments lead to lower nurse burnout and higher patient satisfaction. J Nurs Care Qual 36(1):7–13

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor (2022) Occupational outlook handbook, registered nurses. http://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/registered-nurses.htm . Accessed 15 Sept 2022

Burke EK, Curtois T (2014) New approaches to nurse rostering benchmark instances. Eur J Oper Res 237(1):71–81

Campbell GM (1999) Cross-utilization of workers whose capabilities differ. Manage Sci 45(5):722–732

Chang AM, Cohen D, Lin A, Augustine J, Handel D, Howell E, Kim H, Pines J, Schuur JD, McConnell KJ, Sun BC (2018) Hospital strategies for reducing emergency department crowding: a mixed-methods study. Ann Emerg Med 71(4):497-505.e4

Cheang B, Li H, Lim A, Rodrigues B (2003) Nurse rostering problems––a bibliographic survey. Eur J Oper Res 151(3):447–460

Chhatwal J, Alagoz O, Burnside ES (2010) Optimal breast biopsy decision-making based on mammographic features and demographic factors. Oper Res 58(6):1577–1591

Cho D, Cattani K (2019) The patient patient: the performance of traditional versus open-access scheduling policies. Decis Sci 50(4):756–785

Cho E, Sloane DM, Kim EY, Kim S, Choi M, Yoo IY, Lee HS, Aiken LH (2015) Effects of nurse staffing, work environments, and education on patient mortality: An observational study. Int J Nurs Stud 52(2):535–542

Cho SH, Ketefian S, Barkauskas VH, Smith DG (2003) The effects of nurse staffing on adverse events, morbidity, mortality, and medical costs. Nurs Res 52(2):71–79

Dall TM, Chen YJ, Seifert RF, Maddox PJ, Hogan PF (2009) The economic value of professional nursing. Med Care 47(1):97–104

Daskin MS, Dean LK (2005) Location of health care facilities. Operations research and health care: a handbook of methods and applications. In: Brandeau M, Sainfort F, Pierskalla WP (eds). Kluwer Academic Publishers. Chapter 3, pp 43–76

De Véricourt F, Jennings OB (2011) Nurse staffing in medical units: a queueing perspective. Oper Res 59(6):1320–1331

Denton BT, Miller AJ, Balasubramanian HJ, Huschka TR (2010) Optimal allocation of surgery blocks to operating rooms under uncertainty. Oper Res 58(4):802–816

Dobson G, Hasija S, Pinker EJ (2011) Reserving capacity for urgent patients in primary care. Prod Oper Manag 20(3):456–473

Dobson G, Lee HH, Pinker E (2010) A model of ICU bumping. Oper Res 58(6):1564–1576

Dobson G, Pinker E, Van Horn RL (2009) Division of labor in medical office practices. Manuf Serv Oper Manag 11(3):525–537

Easton FF (2011) Cross-training performance in flexible labor scheduling environments. IIE Transaction 43(8):589–603

Faridimehr S, Venkatachalam S, Chinnam RB (2021) Managing access to primary care clinics using scheduling templates. Health Care Manag Sci 24(3):482–498

Fagerström L, Kinnunen M, Saarela J (2018) Nursing workload, patient safety incidents and mortality: an observational study from Finland. BMJ Open 8(e016367):1–10

Google Scholar

Gnanlet A, Gilland WG (2009) Sequential and simultaneous decision making for optimizing health care resource flexibilities. Decis Sci 40(2):295–326

Gnanlet A, Gilland WG (2014) Impact of productivity on cross-training configurations and optimal staffing decisions in hospitals. Eur J Oper Res 238(1):254–269

Green, L.V. (2005). Capacity Planning and Management in Hospitals. In: Brandeau, M.L., Sainfort, F., Pierskalla, W.P. (eds) Operations Research and Health Care. International Series in Operations Research & Management Science, vol 70. Springer, Boston, MA. pp 15-41

Green LV, Savin S (2008) Reducing delays for medical appointments: A queueing approach. Oper Res 56(6):1526–1538

Griffiths P, Ball J, Bloor K, Böhning D, Briggs J, Dall’Ora C, De Iongh A, Jones J, Kovacs C, Maruotti A, Meredith P, Prytherch D, Saucedo AR, Redfern O, Schmidt P, Sinden N, Smith G (2018) Nurse staffing levels, missed vital signs and mortality in hospitals: Retrospective longitudinal observational study. Health Serv Deliv Res 6(38)

Gupta D, Denton B (2008) Appointment scheduling in health care: Challenges and opportunities. IIE Transaction 40(9):800–819

Gurses AP, Carayon P, Wall M (2009) Impact of performance obstacles on intensive care nurses’ workload, perceived quality and safety of care, and quality of working life. Health Serv Res 44(2p1):422–443

Halawa F, Madathil SC, Gittler A, Khasawneh MT (2020) Advancing evidence-based healthcare facility design: A systematic literature review. Health Care Manag Sci 23(3):453–480

Halm EA, Lee C, Chassin MR (2002) Is volume related to outcome in health care? A systematic review and methodologic critique of the literature. Ann Intern Med 137(6):511–520

Hopp WJ, Tekin E, Van Oyen MP (2004) Benefits of skill chaining in serial production lines with cross-trained workers. Manage Sci 50(1):83–98

Hugonnet S, Chevrolet J, Pittet D (2007) The effect of workload on infection risk in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 35(1):76–81

Institute of Medicine (2001) Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. National Academies Press, Washington D.C

Iwashyna TJ, Kramer AA, Kahn JM (2009) Intensive care unit occupancy and patient outcomes. Crit Care Med 37(5):1545–1557

Jones CB (2005) The costs of nurse turnover, part 2: application of the nursing turnover cost calculation methodology. J Nurs Adm 35(1):41–49

Jordan WC, Inman RR, Blumenfeld DE (2004) Chained cross-training of workers for robust performance. IIE Trans 36(10):953–967

Kahn JM, Goss CH, Heagerty PJ, Kramer AA, O’Brien CR, Rubenfeld GD (2006) Hospital volume and the outcomes of mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med 355(1):41–50

Kanai Y, Takagi H (2021) Markov chain analysis for the neonatal inpatient flow in a hospital. Health Care Manag Sci 24(1):92–116

Kane RL, Shamliyan TA, Mueller C, Duval S, Wilt TJ (2007) The association of registered nurse staffing levels and patient outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Care 45(12):1195–1204

Kosel K, Olivo T (2002) The business case for workforce stability. VHA Research Series 7:1–16

Lankshear AJ, Sheldon TA, Maynard A (2005) Nurse staffing and healthcare outcomes: a systematic review of the international research evidence. Adv Nurs Sci 28(2):163–174

Lee DKK, Zenios SA (2009) Optimal capacity overbooking for the regular treatment of chronic conditions. Oper Res 57(4):852–865

Legrain A, Omer J, Rosat S (2020) An online stochastic algorithm for a dynamic nurse scheduling problem. Eur J Oper Res 285(1):196–210

Lim GJ, Mobasher A, Côté MJ (2012) Multi-objective nurse scheduling models with patient workload and nurse preferences. Management 2(5):149–160

Lin H (2014) Revisiting the relationship between nurse staffing and quality of care in nursing homes: An instrumental variables approach. J Health Econ 37:13–24

Lin YK, Chou YY (2020) A hybrid genetic algorithm for operating room scheduling. Health Care Manag Sci 23(2):249–263

Lopez V, Anderson J, West S, Cleary M (2022) Does the COVID-19 pandemic further impact nursing shortages? Issues Ment Health Nurs 43(3):293–295

Ma C, McHugh MD, Aiken LH (2015) Organization of hospital nursing and 30-day readmissions in Medicare patients undergoing surgery. Med Care 53(1):65–70

Mandelbaum A, Momcilovic P, Tseytlin Y (2012) On fair routing from emergency departments to hospital wards: QED queues with heterogeneous servers. Manage Sci 58(7):1273–1291

May JH, Spangler WE, Strum DP, Vargas LG (2011) The surgical scheduling problem: Current research and future opportunities. Prod Oper Manag 20(3):392–405

McCue M, Mark BA, Harless DW (2003) Nurse staffing, quality, and financial performance. J Health Care Finance 29(4):54–76

Mousavi H, Darestani SA, Azimi P (2021) An artificial neural network based mathematical model for a stochastic health care facility location problem. Health Care Manag Sci 24(3):499–514

Musy SN, Endrich O, Leichtle AB, Griffiths P, Nakas CT, Simon M (2020) Longitudinal study of the variation in patient turnover and patient-to-nurse ratio: Descriptive analysis of a Swiss University Hospital. J Med Internet Res 22(4):e15554

Needleman J, Buerhaus P, Mattke S, Stewart M, Zelevinsky K (2002) Nurse-staffing levels and the quality of care in hospitals. N Engl J Med 346(22):1715–1722

Needleman J, Buerhaus P, Pankratz VS, Leibson CL, Stevens SR, Harris M (2011) Nurse staffing and inpatient hospital mortality. N Engl J Med 364(11):1037–1045

Needleman J, Buerhaus PI, Stewart M, Zelevinsky K, Mattke S (2006) Nurse staffing in hospitals: Is there a business case for quality? Health Aff 25(1):204–211

Newhouse RP, Johantgen M, Pronovost PJ, Johnson E (2005) Perioperative nurses and patient outcomes—mortality, complications, and length of stay. AORN J 81(3):508–528

NSI Nursing Solutions, Inc. (2021) 2021 NSI national health care retention & rn staffing report. https://www.emergingrnleader.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/NSI_National_Health_Care_Retention_Report.pdf . Accessed 12 Mar 2023

Oakley D, Onggo BS, Worthington D (2020) Symbiotic simulation for the operational management of inpatient beds: model development and validation using Δ-method. Health Care Manag Sci 23(1):153–169

OECD/European Union (2014) Health at a glance: Europe 2014. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/health_glance_eur-2014-en

Olivares M, Terwiesch C, Cassorla L (2008) Structural estimation of the newsvendor model: an application to reserving operating room time. Manage Sci 54(1):41–55

Papanicolas I, Woskie LR, Jha AK (2018) Health care spending in the United States and other high-income countries. JAMA 319(10):1024–1039

Peelen L, de Keizer N, Peek N, Jan Scheffer G, van der Voort P, de Jonge E (2007) The influence of volume and intensive care unit organization on hospital mortality in patients admitted with severe sepsis: a retrospective multicentre cohort study. Crit Care 11(2):1–10

Phibbs C, Bartel A, Giovannetti B, Schmitt S, Stone P (2009) The impact of nurse staffing and contract nurses on patient outcomes: New evidence from longitudinal data. Working Paper, Columbia Business School

Phibbs CS, Baker LC, Caughey AB, Danielsen B, Schmitt SK, Phibbs RH (2007) Level and volume of neonatal intensive care and mortality in very-low-birth-weight infants. N Engl J Med 356(21):2165–2175

Pinker EJ, Shumsky RA (2000) The efficiency-quality trade-off of cross-trained workers. Manuf Serv Oper Manag 2(1):32–48

Pronovost PJ, Dang D, Dorman T, Lipsett PA, Garrett E, Jenckes M, Bass EB (2001) Intensive care unit nurse staffing and the risk for complications after abdominal aortic surgery. Eff Clin Pract 4(5):199–206

Rauner MS, Gutjahr WJ, Heidenberger K, Wagner J, Pasia J (2010) Dynamic policy modeling for chronic diseases: Metaheuristic-based identification of pareto-optimal screening strategies. Oper Res 58(5):1269–1286

Rerkjirattikal P, Huynh VN, Olapiriyakul S, Supnithi T (2020) A goal programming approach to nurse scheduling with individual preference satisfaction. Math Probl Eng 2020:2379091

Rothberg MB, Abraham I, Lindenauer PK, Rose DN (2005) Improving nurse-to-patient staffing ratios as a cost-effective safety intervention. Med Care 43(8):785–791

Schoenfelder J, Bretthauer KM, Wright PD, Coe E (2020) Nurse scheduling with quick-response methods: Improving hospital performance, nurse workload, and patient experience. Eur J Oper Res 283(1):390–403

Shehadeh KS, Padman R (2021) A distributionally robust optimization approach for stochastic elective surgery scheduling with limited intensive care unit capacity. Eur J Oper Res 290(3):901–913

Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR, McHugh MD, Ludwig JM, Smith HL, Niknam BA, Even-Shoshan O, Fleisher LA, Kelz RR, Aiken LH (2016) Comparison of the value of nursing work environments in hospitals across different levels of patient risk. JAMA Surg 151(6):527–536

Sims CE (2003) Increasing clinical, satisfaction, and financial performance through nurse-driven process improvement. J Nurs Adm 33(2):68–75

Sloane DM, Smith HL, McHugh MD, Aiken LH (2018) Effect of changes in hospital nursing resources on improvements in patient safety and quality of care: a panel study. Med Care 56(12):1001–1008

Spence Laschinger HK, Leiter MP (2006) The impact of nursing work environments on patient safety outcomes: the mediating role of burnout engagement. J Nurs Adm 36(5):259–267

Spetz J (2004) California’s minimum nurse-to-patient ratios: the first few months. J Nurs Adm 34(12):571–578

Stanton MW, Rutherford MK (2004) Hospital nurse staffing and quality of care. Research in Action, Issue 14. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, Maryland

Sturm H, Rieger MA, Martus P, Ueding E, Wagner A, Holderried M, Maschmann J (2019) Do perceived working conditions and patient safety culture correlate with objective workload and patient outcomes: A cross-sectional explorative study from a German university hospital. Plos One 14(1):e0209487 (1-19)

Theokary C, Ren ZJ (2011) An empirical study of the relations between hospital volume, teaching status, and service quality. Prod Oper Manag 20(3):303–318

Thompson S, Nunez M, Garfinkel R, Dean MD (2009) OR practice–-Efficient short-term allocation and reallocation of patients to floors of a hospital during demand surges. Oper Res 57(2):261–273

Tourangeau AE, Doran DM, Hall LMG, O’Brien Pallas L, Pringle D, Tu JV, Cranley LA (2007) Impact of hospital nursing care on 30-day mortality for acute medical patients. J Adv Nurs 57(1):32–44

Tsai SC, Yeh Y, Kuo CY (2021) Efficient optimization algorithms for surgical scheduling under uncertainty. Eur J Oper Res 293(2):579–593

U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) (2009) Hospital emergency departments: crowding continues to occur, and some patients wait longer than recommended time frames. Report GAO-09-347

Valouxis C, Gogos C, Goulas G, Alefragis P, Housos E (2012) A systematic two phase approach for the nurse rostering problem. Eur J Oper Res 219(2):425–433

Volland J, Fügener A, Schoenfelder J, Brunner JO (2017) Material logistics in hospitals: a literature review. Omega 69:82–101

Wang WY, Gupta D (2011) Adaptive appointment systems with patient preferences. Manuf Serv Oper Manag 13(3):373–389

White DL, Froehle CM, Klassen KJ (2011) The effect of integrated scheduling and capacity policies on clinical efficiency. Prod Oper Manag 20(3):442–455

Wolbeck L, Kliewer N, Marques I (2020) Fair shift change penalization scheme for nurse rescheduling problems. Eur J Oper Res 284(3):1121–1135

Wright PD, Bretthauer KM (2010) Strategies for addressing the nursing shortage: Coordinated decision making and workforce flexibility. Decis Sci 41(2):373–401

Wright PD, Bretthauer KM, Côté MJ (2006) Reexamining the nurse scheduling problem: Staffing ratios and nursing shortages. Decis Sci 37(1):39–70

Wynendaele H, Willems R, Trybou J (2019) Systematic review: Association between the patient–nurse ratio and nurse outcomes in acute care hospitals. J Nurs Manag 27(5):896–917

Yankovic N, Green LV (2011) Identifying good nursing levels: A queuing approach. Oper Res 59(4):942–955

Yu X, Bayram A (2021) Managing capacity for virtual and office appointments in chronic care. Health Care Manag Sci 24(4):742–767

Zhang X, Tai D, Pforsich H, Lin VW (2018) United States registered nurse workforce report card and shortage forecast: a revisit. Am J Med Qual 33(3):229–236

Download references

No funds, grants, or other support was received.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Management, College of Business and Economics, California State University, Fullerton, Fullerton, CA, 92831, USA

David D. Cho

Operations and Decision Technologies Department, Kelley School of Business, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, 47405, USA

Kurt M. Bretthauer

Health Care Operations / Health Information Management, University of Augsburg, 86159, Augsburg, Germany

Jan Schoenfelder

School of Management, Lancaster University Leipzig, 04109, Leipzig, Germany

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, analysis, and manuscript writing were performed by David D. Cho, Kurt M. Bretthauer, and Jan Schoenfelder. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to David D. Cho .

Ethics declarations

Declarations, conflict of interest.

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

1.1 Three case study hospitals

We collected nursing data from three hospitals in the United States. One is located in California and two are located in Indiana. They range in size from 350 to 550 beds. We obtained information on nurse wages, shift types, staff size and mix, shift preferences and availability, patient-to-nurse ratios, and limited bed demand data. Note that detailed and extensive historical patient flow and demand data were not available. Due to the limited bed demand data, we also use data from the American Hospital Association and California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development to estimate inpatient demand and create hospital size categories, as described in the next subsection. The three hospitals differ in size and nurse wages. Table 5 summarizes the data.

1.2 American hospital association (AHA) data

In addition to the three case study hospitals, we acquired 2015 AHA Annual Survey data from California, New York, and Texas for our numerical experiments. From the dataset, we consider hospitals with the primary service code of “general medical and surgical” and that are coded as either “nongovernment, not-for-profit” or “corporation-owned, for-profit”. We exclude hospitals that do not have any general medical and surgical adult beds. After filtering, the data set contains information on 493 hospitals across the three states of California, New York, and Texas.

Based on the 2015 AHA Annual Survey data, we created four hospital size categories, as shown in Table 6 . While the range of total facility inpatient days for category 3 is relatively wide, the impact of hospital size on the policy patient-to-nurse ratio is still captured effectively with the four categories, as shown by the results in Section 5.1 .

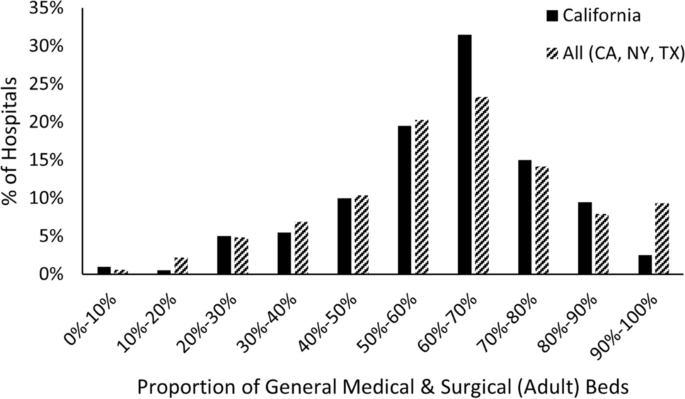

Figure 11 reports the proportion of general medical and surgical beds in the included hospitals according to the AHA data. The AHA data provides total hospital-wide inpatient days, but not unit-specific inpatient days, which is what we need. Therefore, based on Fig. 11 , we estimate that the inpatient days for med/surg units are around 50–80% of the total hospital-wide inpatient days.

Distribution of medical and surgical bed proportion for hospitals in AHA data set

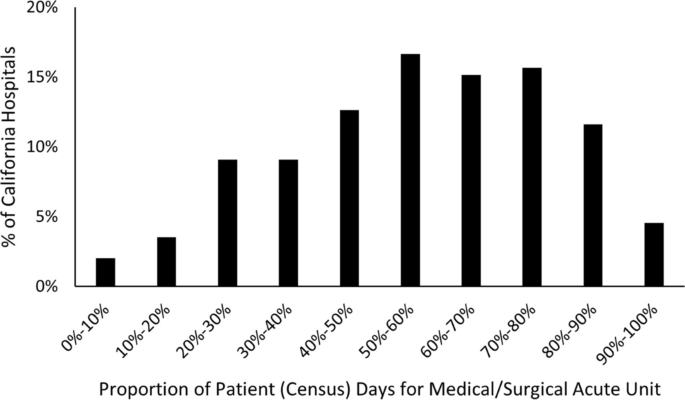

1.3 California office of statewide health planning and development (OSHPD) data

To further support our estimate of med/surg inpatient days, we also acquired data from the “2014–2015 Fiscal Year Hospital Annual Financial Disclosure Report” provided by California’s Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD). While this data set is limited to hospitals in California, it includes unit-specific information regarding beds and patient (census) days. After applying the identical filter as used for the AHA data set, the OSHPD data set provides information on 198 hospitals in California. Figure 12 shows that our assumption of inpatient days for the med/surg unit being around 50–80% of the total hospital-wide inpatient days is reasonable.

Distribution of medical and surgical patient days proportion for California hospitals in OSHPD data set

Appendix B. Limiting undesirable shifts for each nurse

In Section 5.3 , we minimize the total number of undesirable shifts without incurring any additional schedule costs, but we do not limit the number of undesirable shifts for each nurse. Thus, it is theoretically possible for the remaining undesirable shifts to be assigned disproportionately to a small number of nurses. While this was not a major issue for our numerical experiments in Section 5.3 due to the very low number of remaining undesirable shifts with the second objective function, we can also add constraints ( 27 ) and ( 28 ) that limit the number of undesirable shifts along with second objective function ( 23 ).

where \({\overline{US} }_{i}^{UN}\) and \({\overline{US} }_{i}^{FN}\) are upper limits on the number of undesirable shifts assigned to unit and float nurse \(i\) , respectively.

Because we still do not allow additional schedule costs, our optimal costs do not change in this case. Furthermore, we also do not observe any meaningful differences in total number of undesirable shifts compared to the results presented in Section 5.3 as long as \({\overline{US} }_{i}^{UN}\) and \({\overline{US} }_{i}^{FN}\) are not too low. We note that when the limit is too low (for example, 0 or 1 undesirable shift per nurse), the problem sometimes becomes unsolvable for policy PTN ratio of 4:1 due to the insufficient number of available and desirable shifts to stay under the policy PTN for every shift since we do not allow any increase in costs.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cho, D.D., Bretthauer, K.M. & Schoenfelder, J. Patient-to-nurse ratios: Balancing quality, nurse turnover, and cost. Health Care Manag Sci 26 , 807–826 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10729-023-09659-y

Download citation

Received : 17 May 2022

Accepted : 04 October 2023

Published : 29 November 2023

Issue Date : December 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10729-023-09659-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Hospital capacity planning

- Nurse staffing

- Patient-to-nurse ratios

- Quality of care

- Operations research

- Operations management

- Optimization

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Health Care Access & Coverage

What Patient-To-Nurse Ratios Mean for Hospital Patient Health and Outcomes

Pennsylvania legislature pushed to take up patient safety issue it has long avoided.

- Hoag Levins

- Share this page on Twitter

- Share this page on Facebook

- Share this page on LinkedIn

“Should Hospitals be Required to Have a Certain Number of Nurses?” asks a Philadelphia Inquirer headline about the controversy brewing in Harrisburg around the latest efforts to have the Pennsylvania legislature pass a law requiring minimum patient-to-nurse ratios in its hospitals. It’s the latest general media story that seems to infer that this patient-to-nurse issue is a vague, unsettled thing essentially about a nursing labor grievance. But it isn’t. Hard scientific evidence since the 1980s has shown that having insufficient numbers of nurses on a given hospital unit kills and injures more patients than when there are enough nurses available to adequately attend and monitor those patients. The University of Pennsylvania’s School of Nursing and its Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research (CHOPR) have played a leading international role in these decades of research.

In recent years, the number of highly trained nurses in hospitals has been affected by severe and repeated budget cuts that save money by increasing the patient-to-nurse ratios so that more patients are assigned to each nurse, and/or by using less trained and skilled aides to replace registered nurses. After California became the first state to enact a minimum required nurse staffing law for its hospitals in 1999, other hospitals and their lobbying organizations across the country worked hard to prevent similar legislation from being enacted in other states–despite the evidence that not having adequate patient-to-nurse ratios leads to higher mortality rates and worse patient outcomes.

A 12-Year effort

The latest effort to enact a minimum required nurse staffing law in Pennsylvania began early in May with the announcement of both House Bill 106 and Senate Bill 240 , which together are known as the Pennsylvania Patient Safety Act. Prior to this, similar bills have been introduced every year in the Statehouse since 2010. All have died in Republican-controlled committees.

“It is really an example of how in our democracy a couple of individuals for their own personal reasons can deny legislation that is in the public interest from coming up for a vote,” said Founding Director of CHOPR and LDI Senior Fellow Linda Aiken, PhD, RN .

But now, after last November’s elections, Democrats hold the majority in the Pennsylvania House for the first time in 12 years and this new round of nurse ratio bills is being heavily lobbied by nursing organizations, unions, and public health advocates.

The Pennsylvania Patient Safety Act would set the minimum numbers of patients that could be assigned to individual nurses in a hospital’s various departments. Those ratios vary depending upon the nature of the unit’s focus and severity of patients’ conditions and treatment. ( See the list of the exact ratios the Act specifies for various hospital units .)

Nursing Surveillance

It isn’t all that difficult to understand why patient-to-nurse ratios matter if you think of the times you yourself have been in a hospital bed. Nurses function as your minute-to-minute biomedical and wellbeing surveillance system. Although they may appear to be just taking your temperature, providing scheduled pills, or checking your IV set up, they are doing much more invisibly — for every patient under their care.

The wide variety of conditions and illnesses treated in hospitals are all prone to various sorts of disastrous, and often unexpected complications that, if not recognized and immediately addressed, can lead to increased patient deaths, injury, or permanent disability. Together across a ward or unit, nurses function as a critical surveillance system constantly monitoring each patient for the subtle signs that something in their condition has or is about to change for the worse. This invisible surveillance system by highly trained and experienced registered nurses is the most critical–but least understood–of the services they provide.

But the intensity and effectiveness of that surveillance is determined by how many patients a single nurse is charged with caring for. For instance, a registered nurse caring for four seriously ill patients on a shift can conduct a far more comprehensive surveillance on each than if caring 10 or more seriously ill patients on a shift. Research has shown that each additional patient assigned to a registered nurse beyond the optimum ratio significantly increases the risk of preventable death, longer stays, readmissions, and unfavorable patient satisfaction. It directly results in less effective care, poorer patient outcomes, and higher costs of care.

State-Wide PA Hospital Study

In her testimony earlier this month as lead witness before the Pennsylvania House Health Committee hearing on the Patient Safety Act, Aiken detailed the findings of CHOPR’s recent study of patient-to-nurse variations and health outcomes in 114 Pennsylvania hospitals. Conducted according to a National Institutes of Health-funded research protocol, the project used data from more than half a million patients.

In adult medical and surgical units in the 114 hospitals, researchers found patient-to-nurse ratios variations from 3-11. “This is huge variation in a hospital resource that has been shown in hundreds of studies to be associated with a wide range of patient outcomes including mortality, failure to rescue patients with complications, hospital acquired infections, patient satisfaction, length of stay, readmissions, and patient safety,” they noted.