Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Economic Impact of Demonetization: Critical Analysis on Social Impact in India

This research paper discusses the general effects of demonetisation on the economy with the notion of its influence in growth. In the research study, 3 important independent variables are selected that have influences towards the performance of demonetization in India. Indian economy took a momentous shift of banning high denomination notes calculated as 87 percent of total currency in November 2016. The independent variables are social impact, political impact and economic impact. These selected independent variables are the possible factors that might influence the performance of demonetisation recently happened in India. In this research study, 184 sets of questionnaires were prepared and distributed to the targeted respondents who are affected through this, and one more thing the target population is from the southwest part of India called Andhra Pradesh. After the data were collected, IBM SPSS was used to testing the data in order to generate the final result. In the end, the f...

Related Papers

Kaustubh Kalyankar

The impact of demonetization is very huge and significantly major in terms of Indian economy. We have tried in this paper to find what are the factors and impacts of demonetization on the Indian economy and its people. For collection and analysis purpose we have collected and compare about 150 samples of people .The people for research were randomly distributed from the Vellore district located in Tamil Nadu state of India. After conducting analysis we came to the analysis that employment was the only key factor that affected the economy and had a severe impact on demonetization and level of qualification was the only factor that have any relationship with the view of people about whether the demonetization was applied correctly or not. It was also found out that the main reason according to the people for conducting demonetization by government were the cause of removing black money after some other causes which were seem to be important were terrorism and the battle against corrup...

IOSR Journals

The subject matter of this paper is a "Descriptive study on the impact of demonetization in India: From the perspective of society, politics and economic fraternity." Three important independent variables have selected for this study that might have influenced the performance of demonetization that had implemented in India in 2016. They are social impact, political impact and economic impact. The objectives of demonetization were linked to a variety of issues such as limitation of black money, removing forged currency and stopping terrorist funding. Quite a few academics have conducted their own analysis of demonetization and its effects. But most of the research works have addressed the partial and biased effects of the demonetization move since they have been carried out in the early months of the move. This paper finds that, in general, the effects of demonetization on the economy can be said to be balanced and unbiased. This is of major importance for stimulating investment in the economy, which in turn, has wider implications for the overall expansion and development. The main objective of this research is to study the relationship between social, political and economic impact towards demonetization. To conduct this research work, 184 sets of questionnaires were prepared and distributed to the targeted respondents who were affected through this process. The target population is from the state of Kerala, the southern part of India. The IBM SPSS was used to test the data collected in order to produce the final result. The final result shows that demonetization has had significant effect on the areas of social, political and economic areas of life.

SKIREC Publication- UGC Approved Journals

The impact of demonetization was felt in the social, political and economic sector. This action worst affected the poor and the common people. It was a step of moving toward cash less economy. This step was taken to curb the black money to a great extent. Salaried class was not still able to withdraw their salaries from the banks and ATMs as a result of cash deficit. Govt. encouraged doing financial transactions using mobile and other electronic means. Present study is focused on finding of social and economic impacts of demonetization.

India has amongst the highest level of currencies in circulation at 12.1% of GDP. Cash on hand is an estimated at around 3.2% of household assets, higher than investment in equities, or roughly around $ 220 billion. Of this cash, 87% is in the form of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes or roughly Rs 14 lakh crore ($190 billion). Demonetization is a process by which a series of currency will not be legal tender. The series of currency will not be acceptable as valid currency. The demonetization was done in Nov 2016 in as an effort to stop counterfeiting of the current currency notes allegedly used for funding terrorism, as well as a crackdown on black money in the country. Demonetization is a generations' memorable experience and is going to be one of the economic events of our time. Its impact is felt by every Indian citizen. Demonetization affects the economy through the liquidity side. Its effect will be a telling one because nearly 86% of currency value in circulation was withdrawn without replacing bulk of it. As a result of the withdrawal of Rs 500 and Rs 1000 notes, there occurred huge gap in the currency composition as after Rs 100; Rs 2000 is the only denomination.

Ashwani Kumar

Withdrawing units of money from circulation is demonetisation; units of money are denied the status of legal tender. Demonetisation is defined as a process by which currency units will not remain legal tender. The currency notes will not be taken as valid currency. Demonetisation is a step taken by the government where currency units are ceased of its status as legal tender. Demonetisation is a basic condition to change national currency. In other words, demonetisation can be said a change of currency where new units of currency replace the old one. It may involve the introduction of new notes or coins of the same denomination or completely new denomination. The currency has been demonetised thrice in India. The first demonetisation was on 12th January 1946 (Saturday), second on 16th January 1978 (Monday) and the third was on 8th November 2016 (Tuesday). The study attempts to understand meaning and reasons of demonetisation, the sector-wise impact of demonetisation. This study also gives an insight into the positive and negative impact of demonetisation on Indian economy. This study is of descriptive nature so all the required and relevant data have been taken up from various journals, magazines for published papers and websites. Books have also been referred for theoretical information on the topic as required.

International Journal of Research and Analytical Reviews

Jyotika Kaur , DIVNEET BAGGA

‘Demonetisation was a good idea but had bad results’- this was the reaction of the Indian public with regards to demonetisation that was implemented in India in November 2016. The NDA Government implemented demonetisation with the objective to attack the evils like black money, corruption and extremism. The public of India welcomed demonetisation with open hearts though many hardships fell on the citizens which made it difficult to even cope with the daily activities. The GDP of the Nation fell instantly affecting the economy as a whole. The cash intensive nature of the Indian economy was hit badly experiencing a forty five year high unemployment rate, bringing the nation to a stand-still. The position of black money was hit initially but the fake notes of the new 2000 rupee currency again brought back the situation to square one. The paper highlights the impact of demonetisation on the Indian economy along with the impact on black money and unemployment. The primary data was collected to better understand and know the real picture with regards to status of black money and unemployment. The analysis of the impact of demonetisation becomes clear as a time frame of year and a half have passed from the time of its implementation, to learn from the same and formulate more effective policies to solve the problem of black money, corruption and extremism for a long duration.

IRA-International Journal of Management & Social Sciences (ISSN 2455-2267)

Farhat Mohsin

Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education

shyam kapri

Sosanh Albert

International Journal of Engineering and Management Research

Surabhi Srivastava

Demonetisation is an act of cancelling the legal tender status of a currency unit. It is a process when the government pulled out a unit of currency from the total circulation of the economy. The concept of demonetisation is not new, at first French used demonetisation then after most of the countries has adopted demonetisation to clean up the economy from corruption and inflation. India has adopted demonetisation three times: At first in January 1946 when RBI demonetised Rs. 1000 and Rs. 10000 currency notes. and again in 1978 by Moraji Desai of Rs. 1000, 5000, 10000 banknotes were demonetised and both demonetisation were held to eradicate black money. But the term Demonetisation became familiar on 8 November 2016 when P.M. Mr Narendra Damodar Das Modi announced Rs.500 and Rs.1000 currency notes will be no longer as legal tender status from the past midnight to unearth the corruption, black money and terror funding. Therefore this research paper is an attempt to throw the light on...

RELATED PAPERS

Journal of Radiation Research

Adayabalam Balajee

Neurologia medico-chirurgica

Trimurti Nadkarni

Jurnal Eksakta

Muhamad Puji Wibowo

Refiansyah Maruao

Franco Gugliermetti

Anatolia: Turizm Araştırmaları Dergisi

Asker KARTARI

Néphrologie & Thérapeutique

V Connepi 2010

Sofia Rodrigues

PAULINA ESTEFANY DAMIAN SAAVEDRA

American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine

Karim Lakhal

Journal of Cancer Science & Therapy

Ramez Ahmed

Revista Complutense Historia de América

Matías Emiliano Casas

TANMIYAT AL-RAFIDAIN

Actas Del Iii Jornadas Internacionales Upm Sobre Innovacion Educativa Y Convergencia Europea Inece 2099 Iii Jornadas Internacionales Upm Sobre Innovacion Educativa Y Convergencia Europea Inece 2099 24 11 2010 26 11 2010 Madrid Espana

Leonor Rodriguez Sinobas

Computational Statistics & Data Analysis

Pamela Strickland

2010 Information Security Curriculum Development Conference

Christy Chatmon

Electronics Letters

Ramesh Garg

Serials: The Journal for the Serials Community

Michael Anderson

Engineering, Technology & Applied Science Research

Abdul Nasir Laghari

Revista de Ensino de Bioquímica

Leila Maria Beltramini

Journal of Appropriate Technology

BAHIZI Venuste

The Online Journal of Recreation and Sport

ISIK BAYRAKTAR

Virology Journal

Edward Rybicki

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Analyzing the Impact of Intellectual Capital on the Financial Performance: A Comparative Study of Indian Public and Private Sector Banks

- Published: 11 April 2024

Cite this article

- Monika Barak ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6598-3093 1 &

- Rakesh Kumar Sharma 1

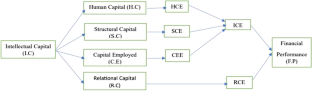

This paper explores the effect of intellectual capital (I.C) on the financial performance (F.P) of 12 public and 17 private sector banks in India. To get a comprehensive viewpoint, the study will try to answer the research question, i.e., Does the intellectual capital affect the financial performance of the Indian banks with respect to their multidimensionality? We used intellectual capital and financial performance as multidimensional constructs (human capital (H.C), capital employed (C.E), structural capital (S.C), and relational capital (R.C) for intellectual capital and return on assets (ROA), return on equity (ROE), return on capital employed (ROCE), and return on sales (ROS) for financial performance). Data were collected over 12 years, specifically from 2010 to 2022 from each bank. This study employed the modified value-added intellectual coefficient (MVAIC) measure as an alternative to the disputed value-added intellectual capital (VAIC) model to address the shortcomings of the previous research. The present study employed advanced longitudinal cointegration techniques to authenticate and validate the results. The fully modified ordinary least squares (FMOLS) method is employed to assess the effectiveness of the intellectual capital. The results suggest a positive relationship between human capital and all financial metrics, except for ROE, in the context of public sector banks. Further efficiency of capital employed and structural capital positively affects public sector bank financial performance indicators like ROA, ROE, ROCE, and ROS. Private sector banks have a negative correlation between relational capital and ROS whereas it demonstrates a positive association with ROCE. Similarly, there is a negative correlation between relational capital and both ROA and ROE in the case of public sector banks. For instance, the MVAIC model improves all financial performance measures except ROA, especially in private sector banking. The findings will assist executives, government officials, and policymakers in quantifying the efficiency and discerning the essential intellectual elements that enhance their effectiveness. Additionally, these findings will aid in devising strategies to foster and enhance their intellectual capacity.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Data Availability

The datasets used and analyzed during this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Adesina, K. S. (2019). Bank technical, allocative and cost efficiencies in Africa: The influence of intellectual capital. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 48 , 419–433.

Article Google Scholar

Ahlawat, D., Sharma, P., & Kumar, S. (2023). A systematic literature review of current understanding and future scope on green intellectual capital. Intangible Capital, 19 (2), 165–188.

Ahmad, W., Tiwari, S. R., Wadhwani, A., Khan, M. A., & Bekiros, S. (2023). Financial networks and systemic risk vulnerabilities: A tale of Indian banks. Research in International Business and Finance, 65 , 101962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2023.101962

Ahmed, Z., Hussin, M. R. A., & Pirzada, K. (2022). The impact of intellectual capital and ownership structure on firm performance. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15 (12), 553.

Al-Azizah, U. S., & Wibowo, B. P. (2023). Impact of intellectual capital on financial performance: Panel evidence from banking industry in Indonesia. Ikonomicheski Izsledvania, 32 (5), 51–65.

Google Scholar

Alhassan, A. L., & Asare, N. (2016). Intellectual capital and bank productivity in emerging markets: Evidence from Ghana. Management Decision, 54 (3), 589–609.

Al-Musali, M. A. K., & Ismail, K. N. I. K. (2014). Intellectual capital and its effect on financial performance of banks: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 164 , 201–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.11.068

Anifowose, M., Abdul Rashid, H. M., Annuar, H. A., & Ibrahim, H. (2018). Intellectual capital efficiency and corporate book value: Evidence from Nigerian economy. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 19 (3), 644–668. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-09-2016-0091

Asutay, M., & Ubaidillah. (2023). Examining the impact of intellectual capital performance on financial performance in Islamic banks. Journal of the Knowledge Economy . https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-023-01114-1

Awwad, M. S., & Qtaishat, A. M. (2023). The impact of intellectual capital on financial performance of commercial banks: The mediating role of competitive advantage. International Journal of Learning and Intellectual Capital, 20 (1), 47–69.

Aybars, A., & Oner, M. (2022). The impact of intellectual capital on firm performance and value: An application of MVAIC on firms listed in Borsa Istanbul. Gazi Journal of Economics and Business , 8 (1). https://doi.org/10.30855/gjeb.2022.8.1.004

Barak, M., & Sharma, R. K. (2023). Investigating the impact of intellectual capital on the sustainable financial performance of private sector banks in India. Sustainability, 15 (2), 1451. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021451

Barathi Kamath, G. (2007). The intellectual capital performance of the Indian banking sector. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 8 (1), 96–123. https://doi.org/10.1108/14691930710715088

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17 (1), 99–120.

Bayraktaroglu, A. E., Calisir, F., & Baskak, M. (2019). Intellectual capital and firm performance: An extended VAIC model. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 20 (3), 406–425. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-12-2017-0184

Bollen, L., Vergauwen, P., & Schnieders, S. (2005). Linking intellectual capital and intellectual property to company performance. Management Decision, 43 (9), 1161–1185.

Buallay, A., Cummings, R., & Hamdan, A. (2019). Intellectual capital efficiency and bank’s performance: A comparative study after the global financial crisis. Pacific Accounting Review, 31 (4), 672–694. https://doi.org/10.1108/PAR-04-2019-0039

Buallay, A., Hamdan, A. M., Reyad, S., Badawi, S., & Madbouly, A. (2020). The efficiency of GCC banks: The role of intellectual capital. European Business Review, 32 (3), 383–404. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-04-2019-0053

Cabrita, M. D. R., & Bontis, N. (2008). Intellectual capital and business performance in the Portuguese banking industry. International Journal of Technology Management, 43 (1/2/3), 212. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.2008.019416

Cao, J., Law, S. H., Samad, A. R. B. A., Mohamad, W. N. B. W., Wang, J., & Yang, X. (2021). Impact of financial development and technological innovation on the volatility of green growth—Evidence from China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28 , 48053–48069.

Chen Goh, P. (2005). Intellectual capital performance of commercial banks in Malaysia. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 6 (3), 385–396. https://doi.org/10.1108/14691930510611120

Chen Goh, P., & Pheng Lim, K. (2004). Disclosing intellectual capital in company annual reports: Evidence from Malaysia. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 5 (3), 500–510.

Choi, I. (2001). Unit root tests for panel data. Journal of International Money and Finance, 20 (2), 249–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5606(00)00048-6

Chowdhury, L. A. M., Rana, T., Akter, M., & Hoque, M. (2018). Impact of intellectual capital on financial performance: Evidence from the Bangladeshi textile sector. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 14 (4), 429–454.

Duho, K. C. T. (2020). Intellectual capital and technical efficiency of banks in an emerging market: A slack-based measure. Journal of Economic Studies, 47 (7), 1711–1732.

Dzenopoljac, V., Yaacoub, C., Elkanj, N., & Bontis, N. (2017). Impact of intellectual capital on corporate performance: Evidence from the Arab region. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 18 (4), 884–903.

Edvinsson, L. (1997). Developing intellectual capital at Skandia. Long Range Planning, 30 (3), 366–373.

Eniola, A. A., Entebang, H., & Sakariyau, O. B. (2015). Small and medium scale business performance in Nigeria: Challenges faced from an intellectual capital perspective. International Journal of Research Studies in Management, 4 (1), 57–71. https://doi.org/10.5861/ijrsm.2015.964

Farooque, O. A., AlObaid, R. O. H., & Khan, A. A. (2023). Does intellectual capital in Islamic banks outperform conventional banks? Evidence from GCC countries. Asian Review of Accounting . https://doi.org/10.1108/ARA-12-2022-0298

Faruq, M. O., Akter, T., & Mizanur Rahman, M. (2023). Does intellectual capital drive bank’s performance in Bangladesh? Evidence from static and dynamic approach. Heliyon, 9 (7), e17656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e17656

Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., Wicks, A. C., Parmar, B. L., & De Colle, S. (2010). Stakeholder theory: The state of the art . Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Gupta, K., & Raman, T. (2021). The nexus of intellectual capital and operational efficiency: The case of Indian financial system. Journal of Business Economics, 91 (3), 283–302.

Hamdan, A. (2018). Intellectual capital and firm performance: Differentiating between accounting-based and market-based performance. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management, 11 (1), 139–151.

Innayah, M. N., Pratama, B. C., & Hanafi, M. M. (2020). The effect of intellectual capital towards firm performance and risk with board diversity as a moderating variable: Study in ASEAN banking firms. JDM (jurnal Dinamika Manajemen), 11 (1), 27–38.

Ismail, K. N. I. K., & Karem, M. A. (2011). Intellectual capital and the financial performance of banks in Bahrain. Journal of Business Management and Accounting, 1 (1), 63–77.

Kamal, M. H. M., Mat, R. C., Rahim, N. A., Husin, N., Ismail, I., et al. (2012). Intellectual capital and firm performance of commercial banks in Malaysia. Asian Economic and Financial Review, 2 (4), 577–590.

Kamaluddin, A., & Rahman, R. A. (2013). The intellectual capital model: The resource-based theory application. International Journal of Learning and Intellectual Capital, 10 (3–4), 294–313.

Kannan, G., & Aulbur, W. G. (2004). Intellectual capital: Measurement effectiveness. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 5 (3), 389–413.

Kapoor, S., & Saihjpal, A. (2022). Intellectual capital and performance of Indian companies: An empirical investigation. International Journal of Learning and Intellectual Capital, 19 (6), 608. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJLIC.2022.126306

Kasoga, P. S. (2020). Does investing in intellectual capital improve financial performance? Panel evidence from firms listed in Tanzania DSE. Cogent Economics & Finance, 8 (1), 1802815. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2020.1802815

Khalique, M., Shaari, J. A. N., Bin Isa, A. H., Bin, M., & Samad, N. B. (2013). Impact of intellectual capital on the organizational performance of Islamic banking sector in Malaysia. Asian Journal of Finance & Accounting, 5 (2), 75. https://doi.org/10.5296/ajfa.v5i2.4005

Kianto, A., Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P., & Ritala, P. (2010). Intellectual capital in service-and product-oriented companies. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 11 (3), 305–325.

Kim, S. Y., & Tran, D. B. (2023). Intellectual capital and performance: Evidence from SMEs in Vietnam. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration . https://doi.org/10.1108/APJBA-08-2022-0343

Kujansivu, P., & Lönnqvist, A. (2007). Investigating the value and efficiency of intellectual capital. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 8 (2), 272–287. https://doi.org/10.1108/14691930710742844

Kwaku Mensah Mawutor, J., Boadi, I., Antwi, S., & Buawolor, A. (2023). Improving banks’ profitability through income diversification and intellectual capital: The sub-Saharan Africa perspective. Cogent Economics & Finance, 11 (2), 2271658. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2023.2271658

Kweh, Q. L., Lu, W.-M., Tone, K., & Nourani, M. (2022). Risk-adjusted banks’ resource-utilization and investment efficiencies: Does intellectual capital matter? Journal of Intellectual Capital, 23 (3), 687–712. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-03-2020-0106

Le, T. D., Ho, T. N., Nguyen, D. T., & Ngo, T. (2022). Intellectual capital – bank efficiency nexus: Evidence from an emerging market. Cogent Economics & Finance, 10 (1), 2127485. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2022.2127485

Levin, A., Lin, C. F., & Chu, C. S. J. (2002). Unit root tests in panel data: Asymptotic and finite-sample properties. Journal of Econometrics, 108 (1), 1–24.

Liu, C.-H. (2017). Creating competitive advantage: Linking perspectives of organization learning, innovation behavior and intellectual capital. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 66 , 13–23.

Madani, F. A., Hosseini, K., Kordnaeij, A., & Isfahani, M. (2015). Intellectual capital: Investigating the role of customer citizenship behavior and employee citizenship behavior in banking industry in Iran. Management and Administrative Sciences Review, 4 (4), 736–747.

Maddala, G. S., & Wu, S. (1999). A comparative study of unit root tests with panel data and a new simple test. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 61 (S1), 631–652. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0084.0610s1631

Majumder, M. T. H., Ruma, I. J., & Akter, A. (2023). Does intellectual capital affect bank performance? Evidence from Bangladesh LBS Journal of Management & Research, ahead-of-print . https://doi.org/10.1108/LBSJMR-05-2022-0016

Martens, W. (2023). Exploring the link between intellectual capital, technical efficiency and income diversity and banks performance: Insights from Taiwan. Qeios . https://doi.org/10.32388/ITMIAU

Meles, A., Porzio, C., Sampagnaro, G., & Verdoliva, V. (2016). The impact of the intellectual capital efficiency on commercial banks performance: Evidence from the US. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, 36 , 64–74.

Mohapatra, S., Jena, S. K., Mitra, A., & Tiwari, A. K. (2019). Intellectual capital and firm performance: Evidence from Indian banking sector. Applied Economics, 51 (57), 6054–6067. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2019.1645283

Mollah, M. A. S., & Rouf, M. A. (2022). The impact of intellectual capital on commercial banks’ performance: Evidence from Bangladesh. Journal of Money and Business, 2 (1), 82–93.

Nadeem, M., Gan, C., & Nguyen, C. (2018). The importance of intellectual capital for firm performance: Evidence from Australia. Australian Accounting Review, 28 (3), 334–344.

Nazari, J. A., & Herremans, I. M. (2007). Extended VAIC model: Measuring intellectual capital components. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 8 (4), 595–609. https://doi.org/10.1108/14691930710830774

Nguyen, N. T. (2023). The impact of intellectual capital on service firm financial performance in emerging countries: The case of Vietnam. Sustainability, 15 (9), 7332.

Nimtrakoon, S. (2015). The relationship between intellectual capital, firms’ market value and financial performance: Empirical evidence from the ASEAN. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 16 (3), 587–618. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-09-2014-0104

North, K., & Kumta, G. (2018). Knowledge management: Value creation through organizational learning . Springer.

Ousama, A. A., Hammami, H., & Abdulkarim, M. (2019). The association between intellectual capital and financial performance in the Islamic banking industry: An analysis of the GCC banks. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management, 13 (1), 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMEFM-05-2016-0073

Ozkan, N., Cakan, S., & Kayacan, M. (2017). Intellectual capital and financial performance: A study of the Turkish Banking Sector. Borsa Istanbul Review, 17 (3), 190–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2016.03.001

Petty, R., & Guthrie, J. (2000). Intellectual capital literature review: Measurement, reporting and management. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 1 (2), 155–176.

Poh, L. T., Kilicman, A., & Ibrahim, S. N. I. (2018). On intellectual capital and financial performances of banks in Malaysia. Cogent Economics & Finance, 6 (1), 1453574. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2018.1453574

Prasojo, P., Yadiati, W., Fitrijanti, T., & Sueb, M. (2022). Cross-region comparison intellectual capital and its impact on islamic banks performance. Economies, 10 (3), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10030061

Pulic, A. (1998). Measuring the performance of intellectual potential in the knowledge economy. In the 2nd McMaster Word Congress on measuring and managing intellectual capital by the Austrian team for intellectual potential . McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada.

Pulic, A. (2004). Intellectual capital–does it create or destroy value? Measuring Business Excellence, 8 (1), 62–68.

Rehman, A. U., Aslam, E., & Iqbal, A. (2022). Intellectual capital efficiency and bank performance: Evidence from islamic banks. Borsa Istanbul Review, 22 (1), 113–121.

Riahi-Belkaoui, A. (2003). Intellectual capital and firm performance of US multinational firms: A study of the resource-based and stakeholder views. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 4 (2), 215–226.

Sardo, F., & Serrasqueiro, Z. (2017). A European empirical study of the relationship between firms’ intellectual capital, financial performance and market value. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 18 (4), 771–788. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-10-2016-0105

Sardo, F., & Serrasqueiro, Z. (2018). Intellectual capital, growth opportunities, and financial performance in European firms: Dynamic panel data analysis. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 19 (4), 747–767.

Smriti, N., & Das, N. (2018). The impact of intellectual capital on firm performance: A study of Indian firms listed in COSPI. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 19 (5), 935–964. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-11-2017-0156

Soewarno, N., & Tjahjadi, B. (2020). Measures that matter: An empirical investigation of intellectual capital and financial performance of banking firms in Indonesia. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 21 (6), 1085–1106. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-09-2019-0225

Sohel Rana, Md., & Hossain, S. Z. (2023). Intellectual capital, firm performance, and sustainable growth: A study on DSE-listed nonfinancial companies in Bangladesh. Sustainability, 15 (9), 7206. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097206

Stewart, T. A. (1997). Intellectual capital: The new wealth of organizations . Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group. Inc.

Taneja, M., Kiran, R., & Bose, S. C. (2024). Assessing entrepreneurial intentions through experiential learning, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial attitude. Studies in Higher Education, 49 (1), 98–118.

Ting, I. W. K., Chen, F. C., Kweh, Q. L., Sui, H. J., & Le, H. T. M. (2021). Intellectual capital and bank branches’ efficiency: An integrated study. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 23 (4), 840–863.

Tiwari, R., & Vidyarthi, H. (2018). Intellectual capital and corporate performance: A case of Indian banks. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 8 (1), 84–105. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAEE-07-2016-0067

Tiwari, R., Vidyarthi, H., & Kumar, A. (2023). Nexus between intellectual capital and bank productivity in India. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 16 (1), 54.

Tran, D. B., & Vo, D. H. (2018). Should bankers be concerned with Intellectual capital? A study of the Thai banking sector. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 19 (5), 897–914.

Tran, N. P., & Vo, D. H. (2020). Human capital efficiency and firm performance across sectors in an emerging market. Cogent Business & Management, 7 (1), 1738832. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1738832

Ullah, A., Pinglu, C., Ullah, S., Qian, N., & Zaman, M. (2023). Impact of intellectual capital efficiency on financial stability in banks: Insights from an emerging economy. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 28 (2), 1858–1871. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.2512

Ulum, I., Ghozali, I., & Purwanto, A. (2014). Intellectual capital performance of Indonesian banking sector: A modified VAIC (M-VAIC) perspective. International Journal of Finance & Accounting, 6 (2), 103–123.

Ulum, I., Kharismawati, N., & Syam, D. (2017). Modified value-added intellectual coefficient (MVAIC) and traditional financial performance of Indonesian biggest companies. International Journal of Learning and Intellectual Capital, 14 (3), 207–219.

Umar, A., & Dandago, K. I. (2023). Knowledge economy: How intellectual capital drives financial performance of non-financial service firms in Nigeria. FUDMA Journal of Accounting and Finance Research [FUJAFR], 1 (2), 113–122. https://doi.org/10.33003/fujafr-2023.v1i2.42.113-122

Vidyarthi, H. (2019). Dynamics of intellectual capitals and bank efficiency in India. The Service Industries Journal, 39 (1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2018.1435641

Vishnu, S., & Kumar Gupta, V. (2014). Intellectual capital and performance of pharmaceutical firms in India. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 15 (1), 83–99.

Wang, M. (2011). Measuring intellectual capital and its effect on financial performance: Evidence from the capital market in Taiwan. Frontiers of Business Research in China, 5 (2), 243–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11782-011-0130-7

Weqar, F., & Haque, S. M. I. (2020). Intellectual capital and corporate financial performance in India’s central public sector enterprises. International Journal of Learning and Intellectual Capital, 17 (1), 77. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJLIC.2020.105323

Weqar, F., & Haque, S. M. I. (2022). The influence of intellectual capital on Indian firms’ financial performance. International Journal of Learning and Intellectual Capital, 19 (2), 169. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJLIC.2022.121249

Weqar, F., Khan, A. M., & Haque, S. M. I. (2020). Exploring the effect of intellectual capital on financial performance: A study of Indian banks. Measuring Business Excellence, 24 (4), 511–529. https://doi.org/10.1108/MBE-12-2019-0118

Wernerfelt, B. (1995). The resource-based view of the firm: Ten years after. Strategic Management Journal, 16 (3), 171–174.

Widowati, E. H., & Pradono, N. S. H. (2017). Management background, intellectual capital and financial performance of Indonesian bank. KINERJA, 21 (2), 172–187.

Xu, J., & Li, J. (2019). The impact of intellectual capital on SMEs’ performance in China: Empirical evidence from non-high-tech vs high-tech SMEs. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 20 (4), 488–509. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-04-2018-0074

Xu, J., Li, F., Korea University Business School. (2020). The impact of intellectual capital on firm performance: A modified and extended VAIC model. Journal of Competitiveness, 12 (1), 161–176. https://doi.org/10.7441/joc.2010.01.10

Xu, J., & Wang, B. (2019). Intellectual capital performance of the textile industry in emerging markets: A comparison with China and South Korea. Sustainability, 11 (8), 2354. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082354

Xu, J., & Zhang, Y. (2021). Does intellectual capital measurement matter in financial performance? An investigation of Chinese agricultural listed companies. Agronomy, 11 (9), 1872. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11091872

Xu, J., Haris, M., & Irfan, M. (2022). The impact of intellectual capital on bank profitability during COVID-19: A comparison with China and Pakistan. Complexity, 2022 , 1–10.

Xu, J., Haris, M., & Irfan, M. (2023). Assessing intellectual capital performance of banks during COVID-19: Evidence from China and Pakistan. Quantitative Finance and Economics, 7 (2), 356–370. https://doi.org/10.3934/QFE.2023017

Youndt, M. A., Subramaniam, M., & Snell, S. A. (2004). Intellectual capital profiles: An examination of investments and returns. Journal of Management Studies, 41 (2), 335–361.

Zheng, C., Islam, M. N., Hasan, N., & Halim, Md. A. (2022). Does intellectual capital efficiency matter for banks’ performance and risk-taking behavior? Cogent Economics & Finance, 10 (1), 2127484. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2022.2127484

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Thapar Institute of Engineering and Technology, Prem Nagar, Bhadson Road, P.O. Box 32, Patiala, Punjab, 147004, India

Monika Barak & Rakesh Kumar Sharma

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The first author assumed responsibility for the conceptualization, design, and execution of the research project, in addition to doing the statistical analysis. The second author aided in the interpretation of the results. The authors have collectively engaged in an ongoing cycle of rewriting and reviewing the paper, ultimately reaching a consensus on the current version.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Monika Barak .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval.

This article contains no human participant investigations conducted by any of the authors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Barak, M., Sharma, R.K. Analyzing the Impact of Intellectual Capital on the Financial Performance: A Comparative Study of Indian Public and Private Sector Banks. J Knowl Econ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-024-01901-4

Download citation

Received : 18 August 2023

Accepted : 04 March 2024

Published : 11 April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-024-01901-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Indian public and private sector banks

- Intellectual capital

- Resource-based theory

- Stakeholder theory

JEL Classification

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 12 April 2024

Evaluating the effectiveness of training of managerial and non-managerial bank employees using Kirkpatrick’s model for evaluation of training

- Kayenaat Bahl 1 ,

- Ravi Kiran 1 &

- Anupam Sharma 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 508 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

- Business and management

This research employs Kirkpatrick’s model, to assess the efficacy of training programmes for managerial and non-managerial employees in the banking sector using all the four components i.e., Reaction, Learning, Behavior and Results. Data were collected from 402 respondents from public, private and foreign sector banks. SEM-PLS was used to determine the relationship between the levels of the Kirkpatrick’s model for the evaluation of the training programs of the baking sector. The results suggest that all the four levels are interlinked and Kirkpatrick model was effective to evaluate the impact of training programs on employee motivation and bank performance. Reactions of employees (stage 1) have enhanced knowledge, and skills and has a positive and significant influence on learning (stage 2) and Behavior through job performance (stage 3) has a positive impact on results (stage 4). The results reflected that the adjusted R 2 = 0.732 of the managerial level is more than that of the non-managerial level ( R 2 = 0.571). This indicates that the training is more effective on the Managerial level than the Non-Managerial level and that the managerial employees are more skilled and experienced in their jobs. The study is novel and one of the initial contributions to apply Kirkpatrick’s model to banking sector in India.

Introduction

Training is crucial for enhancing employee development by emphasizing productivity optimization to meet customer satisfaction. Banks regard it as the utmost crucial objective. Employee training involves implementing programmes that provide individuals with the requisite knowledge and skills to effectively carry out a particular job or to acquire additional competencies in anticipation of future growth in their professional careers. It is a process that aligns the growth of the employee with the goals and procedures of the organization. The demand for employee training in banks has intensified as a result of the increasing competition in the banking sector. Evaluating the effectiveness of training programmes is a crucial priority for financial institutions. The Indian banking industry is currently facing substantial challenges arising from deregulation, demonetization, digitalization, and bank consolidation. These factors have intensified the need for job enrichment. Irrespective of their qualifications, every bank is required to offer their employees essential training. Induction or orientation is a compulsory training programme for all bank employees worldwide.

Banks are employing supplementary training programmes, in addition to induction programmes, to acquaint their employees with specific skills in anticipation of the introduction of e-banking. The dynamic nature of the environment has required an evaluation of the employee training and development programmes. Rani and Garg ( 2014 ) argue that it is extremely important to create a training culture that is integrated and systematic among bank employees, rather than providing training on an as-needed basis. According to Das ( 2018 ), it is crucial for financial institutions to establish a training system that is comprehensive and includes both quantitative and qualitative elements. In order to accomplish this, it is imperative to create specialized software for skill training and recruit the most highly qualified trainers available to incentivize them to engage in research and cultivate expertize. Furthermore, it is imperative to establish a proficient system for appraising training requirements and assessing performance. The need for enhanced training facilities and evaluation methods in the banking industry highlights the importance of creating a model that can accurately identify the required conditions to reflect the current state of banks.

Kirkpatrick’s Model, developed in 1954, made a substantial contribution to the formulation of strategies aimed at ensuring the acquisition of behavior and skills. The present study assessed the training programmes for banking employees utilizing Kirkpatrick’s four-tiered model. Employing Kirkpatrick’s model for evaluation is crucial for gauging the overall efficacy. This will streamline the process of evaluating whether to continue with the training programme, terminate it, or make any required modifications. The study elucidates the utilization of Kirkpatrick’s model to develop a framework that is effective for the banking sector to evaluate the effectiveness of training for bank employees and to measure the influence of that training on their behavioral results.

The present study is further classified on the basis of the objectives given below:

O1: To examine the reactions of the employees on their learning ability, learning on the behavioral changes of the employees and the impact of the Behavior on the overall Results of the training.

O2: To analyze the impact of training on the Managerial and the Non-Managerial levels of the Banking Sector

O3: To create a Model based on the impact of reactions on learning ability, learning on the behavior of the employees and finally analyzing the results to incorporate changes in the training program separately for both the Managerial and the Non-Managerial levels.

Many researchers employ Kirkpatrick’s Model to evaluate training programmes. As the level of evaluation increases, the process becomes more difficult and time-consuming. The banking industry, being a major contributor to the global gross domestic product, has created employment opportunities for billions of individuals across the globe. Therefore, it is the responsibility of financial institutions to make sure that their staff members receive sufficient training and that the training programmes are regularly evaluated. Training the current staff is a more cost-effective option compared to hiring a high-priced professional. Training is a means by which employees gain organized knowledge to enhance their skills, growth, and cultivate a favorable mindset towards carrying out a particular job. Proficient employees are crucial to a company’s success (Mathur and Pandaya, 2019 ). The significance of offering employees timely and pertinent training is emphasized by the scarcity of resources and the increasing expectations, as elucidated by Benson and Dundis ( 2003 ). Despite assessment being a crucial component of staff training processes, Rajeev et al. ( 2009 ) claim that training programmes are inconsistent and lacking in adequate evaluation. Therefore, drawing from these viewpoints, the present study endeavors to offer a response to the subsequent research question:

Does data from training program implemented at the banking industry support the use of Kirkpatrick’s Model for evaluation (Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick, 2006 )?

The following is the outline of the article. In “Introduction”, we build on what has been learned from the previous literature to show how important the training programmes are and to argue that they should be regularized soon so that performance and results can improve. This section also explains the original Kirkpatrick’s model and how the study built upon it to use a conceptual model to evaluate the impact of training programmes for bank employees. “Literature Review” details a review of previous research that focused on how training affected the outcomes for scientists who have used Kirkpatrick’s Model. “Theoretical Underpinning and hypotheses development” then moves on to talk about how theories and hypotheses development. Also included here is a comprehensive rundown of all the steps needed to evaluate the training methods. “Research Design and Methodology” details the study’s population, sample, scale, and methodology. Using the four stages of Kirkpatrick’s Model—Reaction, Learning, Behavior, and Results—this study aims to construct a PLS-SEM-based model to evaluate training programmes. “Data analysis” provides a comprehensive summary of the investigation’s findings. Discussion, limitations, implications, and suggestions for further study make up “Discussion and conclusion”.

Literature review

Evaluation of training entails systematically reviewing descriptive and judgmental data necessary for making good training decisions (Werner and DeSimone, 2012 ). Assessing the impact of training on the behavioral modifications of the organization’s employees is one of the main procedures to determine the efficacy of the training. An in-depth assessment is required for every training programme before its worth can be determined. The training has a significant impact on how employees behave within an organization. Employees’ improved behavior is a direct result of their training’s emphasis on knowledge retention, skill development, and situational awareness. According to Mohamed et al. ( 2012 ), when it comes to assessing training programmes, Kirkpatrick’s Model works well for knowledge transfer from the individual to the workplace. In the 50 years after its inception, Kirkpatrick’s model has remained the gold standard for assessing the efficacy of training (Saxena, 2020 ). Evaluating training in the banking industry should focus more on the training itself, not just the results, to increase the effectiveness of training for employees. As a result, this study used Kirkpatrick’s four-leveled model to evaluate the training procedure’s effectiveness.

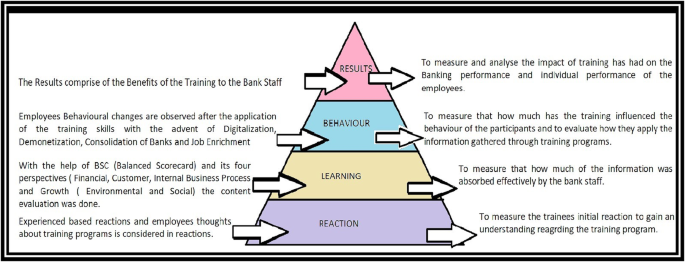

The current study utilized the conceptual framework of Kirkpatrick’s Model (Fig. 1 ) to analyse the impact of training on the banking staff. The evaluation process is broken down into four separate steps according to the Kirkpatrick model. Included in this category are Reactions, Behavior, Learning, and Outcome. Training evaluation is important and crucial because if the results aren’t what were hoped for, then the whole training process was a waste of time and money. Overall, the research has used all four levels of Kirkpatrick’s Model to evaluate the benefits of training programmes in the banking industry. Adapted from Kirkpatrick’s model, Fig. 1 shows the stages used to evaluate the effectiveness of training for banking sector employees. Employee reactions to the training itself make up the first phase. The next step is to put all that training into practice by learning new things that are relevant to what you already know. In the third phase, workers adjust their actions in accordance with what they’ve learned and how they’ve handled certain situations so that the bank can run more smoothly. The last step is to evaluate the findings in the context of the overall efficiency and effectiveness of the banking industry and its personnel.

Kirkpatrick’s Model with respect to Banking Staff Training Programs.

In Level 1 the reactions of the employees to the training programs are considered and measured for further imparting in depth information and skills. Level 1 consists of the various training programs i.e., On the Job training, Off the Job training and Special training being imparted to the trainees and to observe their reactions for the same.

Level 2 consists of the Learning and absorbing the information being imparted with the help of BSC (Balanced Score Card) and its four perspectives i.e., Financial, Customer, Internal Business Process and Growth (Social and Environmental) perspectives.

Level 3 consists of the behavioral changes as a result of the factors affecting the Banking environment and job performance w.r.t. Digitalization, Demonetization, Job Enrichment; and Consolidation of banks.

Level 4 concludes with results for assessing the training programmes’ overall effectiveness, as measured by the benefits to employee motivation and bank performance.

Literature support and application of Kirkpatrick model in different sectors is depicted through Table 1 .

Theoretical underpinning and hypotheses development

The purpose of this research is to look at how the four stages of Kirkpatrick’s Model (Reactions, Learning, and Behavior) interact with each other. This research set out to clarify how these phases differ at the managerial and non-managerial echelons.

In order to compare how well the three different training methods employed, we use the first level of Kirkpatrick’s model. Employees’ knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and performance are all improved through on-the-job training. Creative output, goal attainment, and monetary gain are all profoundly affected. According to Lin and Hsu ( 2017 ), there is a positive relation between on-the-job training and employees’ work performance, personality traits, work behavior, and overall job achievement. Lynch ( 2014 ) found the opposite to be true: that off-the-job training increases the probability of employee turnover, while on-the-job training increases tenure. Since off-the-job training is more targeted and on-the-job training is broad, he argues that women are more inclined to quit an employer when it comes to the former. It is essential to provide staff with specialized training to help them interact with customers effectively, according to Ali and Ratwani ( 2017 ), because employees’ attitudes change and vary in response to customer demands. Workers are empowered to perform to their full potential when they have access to a well-crafted training programme.

H1: There is a difference in reactions to different forms of training (On the Job, Off the Job and Special training) for managerial and non-managerial employees.

H1a: There is a difference in reactions to different forms of training (On the Job, Off the Job and Special training) for managerial employees.

H1b: There is a difference in reactions to different forms of training (On the Job, Off the Job and Special training) for non-managerial employees.

Kirkpatrick’s model associates Level 2 with learning based on training. There can be no greater importance than figuring out how much training has improved knowledge and abilities to positively impact learning. Although there are a variety of models that can be used to evaluate learning, the balanced score card (BSC) is used in this study to examine how reactions impact learning. According to Tuan’s ( 2020 ) research, commercial banks in Vietnam saw substantial gains in performance after adopting the balanced scorecard as an evaluation tool. Organizations can benefit from BSC because it allows for more balanced evaluations of bank and employee performance in addition to overall company performance. Consequently, the BSC and its four perspectives greatly influence employee performance because they make it easier to evaluate their learning capacity.

H2: There is a difference in the learning ability of managerial and non-managerial employees for the four perspectives, viz. financial, internal business process, customer and growth (social and environmental) perspectives.

H3: The reactions to the training (Level 1) has a significant influence on learning (Level 2).

H3a: The reactions to the training (Level 1) has a significant influence on learning (Level 2) for the managerial employees.

H3b: The reactions to the training (Level 1) has a significant influence on learning (Level 1) for the non-managerial employees.

In Kirkpatrick’s model, the impact of actions on productivity in the workplace is investigated at the third level. Thanks to this insightful evaluation data, we can improve the training programmes with confidence. We looked at it in this study by analyzing the efforts of the employees to adjust to the constantly shifting business climate, which encompassed digitalization, demonetization, and bank consolidation. Furthermore, it tackles diversity through enhancing job opportunities. The factors that impact performance and the ways in which employees cope with these factors are the causes of behavioral changes. Workers in the banking industry have been able to improve their efficiency, manage customer relations better, offer services that go beyond their physical capabilities, and handle information management more effectively thanks to digitalization. Based on statistical evidence presented by AL-Ahdal et al. ( 2018 ), demonetization had a substantial impact on the firm’s financial performance. Zunzunegui ( 2018 ) asserts that modern banks give their customers more control over their personal data, which they can then use in partnership with tech companies to improve their services and earn their trust. A number of elements affect employee motivation, including job enrichment, pay, and training opportunities. Each company needs to find a good way to pay their employees and provide them opportunities to grow professionally and personally (Tumi et al. 2021 ). When it comes to banking institutions, high-performance work systems are a great way to boost productivity and output.

Since the merged banks are still following all applicable laws and regulations, Prakash et al. ( 2018 ) state that consolidation has had no effect on the long-term viability of the banking industry. Declining production, branch closures, unregulated customer service, and increased employee workload are the main challenges facing India’s baking industry. Just as Kambar ( 2019 ) asserted. The current research looks at how employees’ actions are correlated with their attempts to adjust to ever-changing corporate conditions, including digitalization, demonetization, bank consolidation, and job enrichment, in order to evaluate performance at this level.

H4: There is a difference in the Behavioral changes of managerial and non-managerial employees w.r.t to the factors influencing the functioning of the banks (Digitalization, Demonetization, Job Enrichment and Consolidation of Banks).

H5a: Learning (level 2) has a significant influence on Behavioral changes (level3) of the managerial and non- managerial employees.

H5a: Learning (level 2) has a significant influence on Behavioral changes (level3) of the managerial employees.

H5b: Learning (level2) has a significant influence on Behavioral changes (level 3) of the non-managerial employees.

Training has several positive effects on performance, including but not limited to: employees’ capacity for self-management, technical skill development, cross-cultural competence, innovation, and tacit expertize (Aguinis and Kraiger, 2009 ). Methods used to educate employees have a significant impact on a company’s image (Clady, 2018 ). Benefits include individual and team financial health as well as national financial health (Janev et al., 2018 ).

To get the most out of training, it’s important to pay attention to the following: need assessment, trainees’ pre-training state, training design and delivery, training evaluation, and training transfer. Providing training to employees has many benefits, but only if the evaluation is done correctly. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the benefits of training in relation to the performance of the bank and the motivation of its employees. A well-organized training programme is essential for all employees, including those in managerial and non-management roles. At the managerial levels, competences and skills matter greatly. Finding qualified candidates for managerial positions at all levels is difficult for most companies. Aslan and Pamukcu ( 2017 ) opine managers are in a position to make choices that might have a major impact on their employees’ emotional and physical well-being. Training that takes place in an organizational context also has an effect on the managers’ mental health and their level of competence. The authors of the study are Yahya and colleagues ( 2018 ). Therefore, it is highly beneficial to have a structured training programme for managers in the banking sector. Research into the impacts of development and training programmes on banking industry managers and non-managers is, therefore, essential, as is an evaluation of the present training programmes’ ability to boost productivity in the banking sector.

H6: Behavioral changes (level 3) has a significant impact on the results, viz. individual and bank performance (level 4) for managerial and non-managerial employees.

H6a: Behavioral changes (level 3) has a significant impact on the results, viz. individual and bank performance (level 4) for managerial employees.

H6b: Behavioral changes (level 3) has a significant impact on the results, viz. individual and bank performance (level 4) for non-managerial employees.

H7: Training has a significant impact on results, viz. individual and bank performance for managerial as well as non-managerial employees.

H7a: Training has a significant impact on results, viz. individual and bank performance for managerial employees.

H7b: Training has a significant impact on results, viz. individual and bank performance for the non-managerial employees.

The next stage is to give details of dataset, research design and methodology. This has been covered in “Data analysis”.

Research design and methodology

Target population and sample size.

Data for the present study were gathered from employees of public, private, and foreign sector banks via a structured questionnaire. The responses pertain to the banks’ contribution to the Indian economy, with public sector banks accounting for 66%, and private sector banks for 28% and foreign banks 6%. A grand total of 402 responses were gathered for the purpose of analysis and interpretation, despite the data collection being impeded by the Covid-19 pandemic. There are 125 banks from the public sector, 55 banks from the private sector, and 15 foreign banks included in the count. The research encompasses the following financial institutions: Axis, Punjab National Bank, SIDBI, IDBI, Yes Bank, J & K bank, Canara, Punjab and Sind Bank, Punjab Gramin Bank, Syndicate Bank, and State Bank of India. Branch heads, assistant managers, regional heads, senior managers, associates, probationary officers, clerks, and chief managers were among the personnel affected. A further division was made into level 1 (managerial personnel) and level 2 (non-managerial personnel). The primary objective of this research is to utilize Kirkpatrick’s Model in order to improve the efficiency of training programmes for managerial and non-managerial personnel in the banking industry.

Research methods

The current investigation employed PLS-SEM model to ascertain the proposed measurement and structural model, which is a widely recognized and utilized technique across multiple research domains. Legate et al. ( 2023 ) found that for many years, Covariance-based Structural Equation Modeling (CB-SEM) has been the method of choice for interpreting intricate interrelationships between latent and observed variables. In 2010, a relatively greater number of published articles incorporated PLS-SEM, as reported by Hair et al. ( 2017 ). Perceptron-Last SEM (PLS-SEM) is a causal predictive methodology within SEM that prioritizes prediction when assessing statistical models designed to provide imaginative explanations (Wold, 1982 ; Sarstedt et al., 2017 ). PLS-SEM is typically applied to data with non-normal distribution and small sample sizes. It facilitates the estimation of values for numerous interdependent relationships among variables and the application of construct measurement (Ittner et al. 1997 ). Given the limited sample size, extensive application, and general acceptance of PLS-SEM, it was deemed appropriate to utilize this method to assess the efficacy of training in the banking industry.

Data analysis

Kirkpatrick’s model for evaluation of effectiveness of training for managerial employees, measurement model, reliability and validity.

Before analyzing Kirkpatrick’s model’s four tiers, construct reliability and validity have been assessed. According to Fornell and Larcker ( 1981 ), factor loadings and average variance extracted (AVE) are used to assess construct convergent validity. Table 2 shows that the AVE ranges from 0.623 to 0.799, meeting Brown and Moore ( 2012 )‘s threshold. Nunnally ( 1978 ) considered composite reliability (CR) values acceptable if they meet 0.70. Cronbach Alpha values range from 0.748 to 0.915, while composite reliability is 0.868 to 0.940. The model has acceptable construct validity and reliability.

Discriminant validity

Discriminant validity was determined by comparing square root of AVE values to inner construct correlations. Table 3 shows that square root of AVE was greater than construct correlations, indicating acceptable discriminant validity. The HTMT criterion aids discriminant validity assessment. As per HTMT criterion, the acceptable level of discriminant validity is suggested to be less than 0.90 between reflective constructs (Hair and Alamer, 2022 ). Kirkpatrick’s Model’s four stages had values below 0.90. Thus, discriminant validity between variables is established. Given that all the stipulations have been fulfilled, it was deemed suitable to proceed with the analysis.

Variance inflation factor

Variance Inflation Factor VIF values greater than 3 reflect the presence of collinearity (Hair, Ringle and Sarstedt 2011 ). As reflected through Table 4 , all VIF values are all lesser than the threshold limit of 3, therefore no indicator was removed.

The study was done with the major objective to examine the effectiveness of training on managerial employees with the help of Kirkpatrick model, basically to examine the impact of training programs on results, viz. employee motivation and bank performance (Table 5 ). Before continuing structural modeling, all factor outer loadings must be checked. All factors had significant values ( p ≤ 0.01) and values above 0.70 (threshold level). No factor was eliminated.

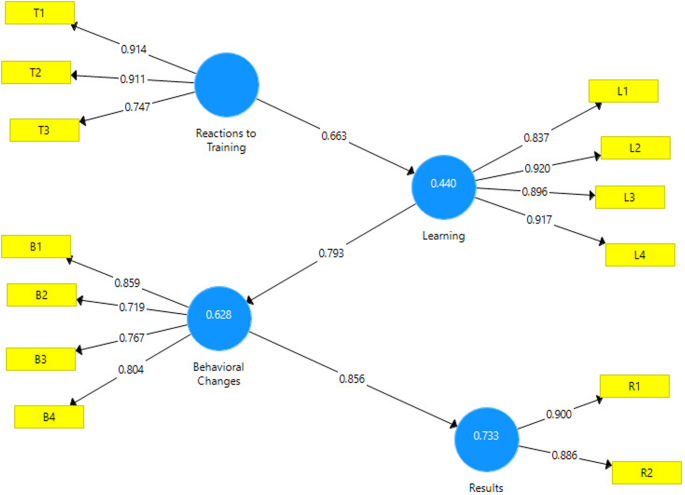

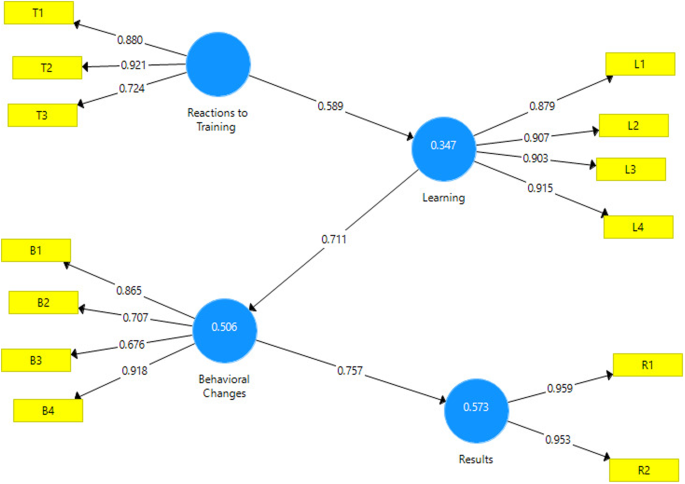

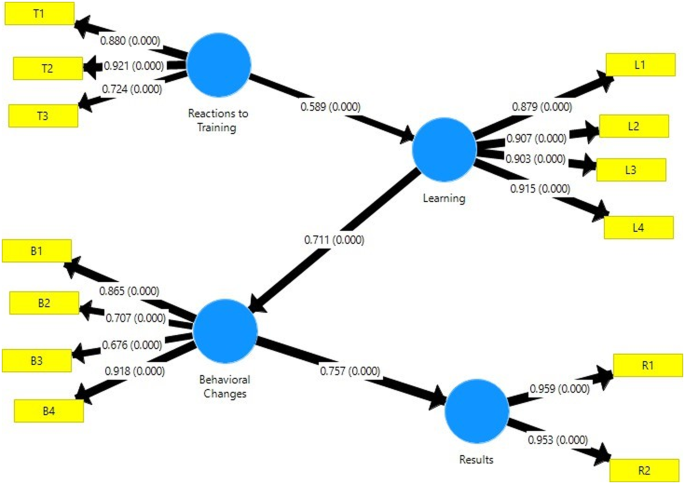

The four levels of Kirkpatrick model are: reaction to training; learning w.r.t. financial, internal business process, customer and growth (social and environmental) perspectives; behavior; and results were taken to analyze the impact of training on the performance of the employees and bank performance (Fig. 2 ). This study examined how reactions affected on-the-job, off-the-job, and special training programmes. The initial hypothesis: H1: There is a difference in reactions to different forms of training (On the Job, Off the Job and Special training) for managerial and non-managerial employees . Table 6 shows that on-the-job training has 0.914 outer weights, off-the-job training 0.911, and special training 0.747. Each is significant and greater than 0.70. Of these three types of training, off-the-job training loaded more items. The least loadings were for special training. H1a: Managerial employees react differently to on-the-job, off-the-job, and special training has been accepted. Findings highlight that special training, which had lower outer weights requires added focus.

Kirkpatrick’s Model for Evaluation of effectiveness of training for Managerial Employees.

The next objective was to assess how much information was retained and whether the training led to financial, customer, internal business process, and growth (social and environmental) learning. The related hypothesis is H2: There is a difference in the learning ability of managerial and non-managerial employees for the four perspectives, viz. financial, internal business process, customer and growth (social and environmental) perspectives . The outer loadings of all four learning perspectives were greater than 0.70, between 0.837 and 0.920, and significant. Thus, the training taught financial, customer, internal business process, and growth (social and environmental) perspectives. Hence H2 has been empirically supported and there is a difference in the learning ability of managerial employees for the four perspectives, viz. financial, internal business process, customer and growth (social and environmental) perspectives at the managerial level.

The next hypothesis linking stage 1 reactions to training to level 2 learning is H3: The reactions to the training (Level 1) has a significant influence on learning (Level 2). As we can see from path co-efficient given in Table 6 and PLS-SEM Fig. 2 , the Beta value for Reactions to Training -> Learning is 0.663 and is significant (T:14.366; p ≤ 0.01). Thus, the reactions to the training (Level 1) has a significant influence on learning (level 2) has been empirically supported.

The third objective of the study was to measure how much training has influenced learning and how learning has influenced employee behavior to evaluate their application of information to deal with factors influencing the banking environment and employee performance, such as digitalization, demonetization, bank consolidation, and job enrichment. This study examined whether behavioral changes helped employees cope with dynamic bank performance factors. The outer weights indicate that employees struggled with demonetization and bank consolidation. These two are recent and may require training. Thus, this must be addressed. Results show that job enrichment and digitalization are more important. New training modules should cover bank consolidation and demonetization. Hence, we can say that hypothesis H4: There is a difference in the Behavioral changes of managerial employees w.r.t to the factors influencing the banks (Digitalization, Demonetization, Job Enrichment and Consolidation of Banks) has been accepted.

The next hypothesis was linking learning with Behavioral changes. As we can see from path co-efficient given in Table 6 and PLS-SEM Fig. 2 , the Beta value for Learning -> Behavioral changes is 0.663 and is significant (T: 21.931; p ≤ 0.01). Thus, H5a: Learning (level 2) has a significant influence on Behavioral changes (level3) of the managerial employees had been empirically supported .

Lastly, the results were measured and analyzed to observe whether the Behavioral changes through job performance (level 3) have a positive impact on results, viz. employee motivation and bank performance (level 4). Outer weights of benefits in terms of employee motivation and bank performance are quite high. Moreover, the Beta value for Behavioral changes -> Results is 0.856 and is significant (T: 35.409; p ≤ 0.01). On the basis of these results, we accept H6a: Behavioral changes (level 3) has a significant impact on the results, viz. individual and bank performance (level 4) for managerial employees.

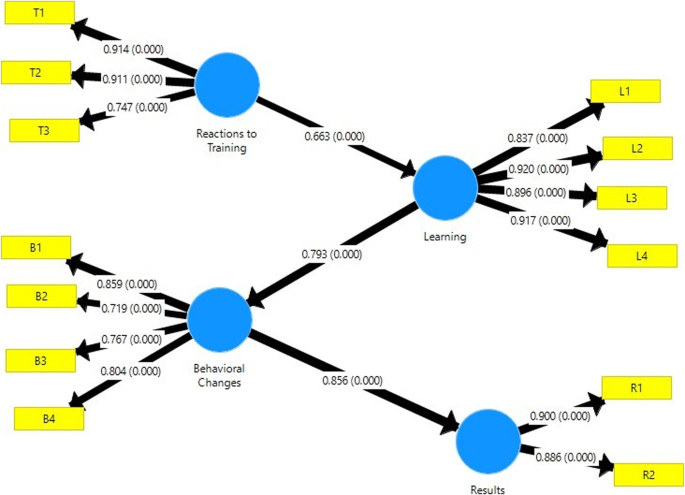

The highlighted paths of bootstrapping results are shown through Fig. 3 . All paths are significant as indicated through the Fig. 3 .

Bootstrapping Model for Kirkpatrick’s Model Evaluation of effectiveness of training for Managerial Employees.

The last hypothesis is H7a: Training has a significant impact on results, viz. individual and bank performance for managerial employees. The effectiveness of training for managerial employees can be gauged from the R 2 value of 0.733 and adj. R 2 value of 0.732 suggesting that this model for managers explains 73.2% of total variation. The total effects are also shown through Table 7 , highlight Reactions to Training -> Learning (0.663); Reactions to Training -> Behavioral Changes (0.526) and Reactions to Training -> Results (0.450) are all significant. Further Learning -> Behavioral Changes (0.793) and Learning -> Results (0.679) are also positive and significant. Lastly, Behavioral Changes -> Results. The beta value is high (0.856) and is also positive and significant. Training-related learning, behavioral changes, and results are all important. Behavioral changes and results from further learning are also positive and significant. Last, Behavioral Changes -> Results is positive and significant. Thus, H7a is empirically supported. The training programmes improved employees’ skills to cope with the dynamic banking sector and factors affecting bank performance, which significantly impacted employee motivation and bank performance.

Kirkpatrick’s model for evaluation of effectiveness of training for non-managerial employees

For the four levels of Kirkpatrick’s model, it is vital to assess the reliability and validity of constructs for non-managerial level. The non-managerial model has AVE between 0.637 and 0.914 (Table 8 ). Composite reliability is 0.873–0.945 and Cronbach Alpha is 0.805–0.923. Model construct validity and reliability are good for non-managerial level too.

As shown through Table 9 , the discriminant validity is also acceptable for non-managerial employees. The square of AVE values is higher than inner construct correlations and HTMT ratios are below 0.90 and are thus acceptable.

Variance Inflation Factor VIF values should not exceed 3. The absence of collinearity is illustrated in Table 10 for the outer VIF are less than 3 (Hair, Ringle, and Sarstedt, 2011 ). Thus, we proceeded with all indicators, for further analysis.

The initial hypothesis associated with the Kirkpatrick model for assessing the impact of training on outcomes is as follows: H1b: Non-managerial employees exhibit distinct responses to various types of training (on-the-job, off-the-job, and special training). The outer weights for On-the-Job training (0.880), Off-the-Job training (0.921), and Special Training (0.724) are detailed in Table 11 . This indicates that employees at the non-managerial level place greater importance on off-the-job training, as it carries the highest loading. This differs from managerial levels, where on-the-job training carries a greater workload. The fact that special training entails reduced workloads for both managerial and non-managerial personnel may suggest that these aspects should be prioritized in future efforts to enhance this form of training. Specialized training is in greater need of attention in light of recent developments in the banking industry. Nonetheless, all of these values exceed 0.70 and were thus significant. As a result, the hypothesis H1b, which states that non-managerial employees respond differently to various types of training (on-the-job, off-the-job, and special training), is supported. At banks, it is time to transition from routine orientation programmes to alternative formats.

The next objective was to investigate the relationship between responses to training (Level 1) and learning (Level 2), specifically from the perspectives of finance, customers, internal business processes, and growth (social and environmental aspects). H2b: There is a difference in the learning ability of non-managerial employees for the four perspectives, viz. financial, internal business process, customer and growth (social and environmental) perspectives. The outer loadings of all the four perspectives of learning were greater than 0.70, in the range of 0.879 and 0.915 with p ≤ 0.01. Hence, it can be inferred that the training led to learning from financial; customer; internal business process; and growth (social and environmental) perspectives. Hence, this hypothesis has been empirically supported for non-managerial employees. The third hypothesis was whether reactions to training (level) were influencing level 2 learning. As we can see from path co-efficient given in Table 12 and Fig. 4 , the Beta value for Reactions to Training ->Learning is 0.589 and is significant (T: 14.058; p ≤ 0.01). Therefore, H3b, which states that non-managerial employees’ reactions to the training (Level 1) have a substantial impact on their learning (Level 2), is supported by empirical evidence.

Kirkpatrick’s Model for Evaluation of effectiveness of training for non-managerial Employees.

After analyzing relation between reactions to training to learning, the next step was to relate learning with behavior. It was to examine whether this learning through behavioral changes helped employees to deal effectively with the dynamic factors, viz. Digitalization, Demonetization, Consolidation of banks and behavioral changes related with Job Enrichment. The loadings for behavioral changes related with Job Enrichment had highest loading indicating its supremacy. From behavioral changes related Consolidation of banks, had the lowest loading, and Demonetization to had lesser loading, indicating that non-managerial employees were not dealing with Consolidation of banks and demonetization effectively. Consequently, we can say that hypothesis H4: There is a difference in the Behavioral changes of non-managerial employees w.r.t to the factors influencing the banks (Digitalization, Demonetization, Job Enrichment and Consolidation of Banks) has been accepted.

The next hypothesis was to see whether learning is related with Behavioral changes. As we can see from path co-efficient given in Table 12 and Fig. 4 , the Beta value for Learning -> Behavioral changes is 0.711 and is significant (T:17.485; p ≤ 0.01). Thus, H5a: Learning (level 2) has a significant influence on Behavioral changes (level3) of the non-managerial employees had been empirically supported.

It is vital to access whether the Behavioral changes through job performance (level 3) have a positive impact on results, viz. employee motivation and bank performance (level 4). Outer loadings of benefits in terms of employee motivation and bank performance are quite high. Moreover, the Beta value for Behavioral changes -> Results is 0.757 and is significant (T:20.302; p ≤ 0.01). On the basis of these results, we accept H6b: Behavioral changes (level 3) have a significant impact on the results, viz. individual and bank performance (level 4) for non-managerial employees. The highlighted paths of bootstrapping results are shown through Fig. 5 . All paths are significant as indicated through the Fig. 5 .

Bootstrapping Model for Kirkpatrick’s Model for Evaluation of effectiveness of training for non-managerial Employees.

The last hypothesis related with non-managerial employees is H7b: Training has a significant impact on results, viz. individual and bank performance for managerial employees. From R 2 Value of 0.573 and adj. R 2 Value of 0.571, it can be indicated that model for non-managers explains 57.1% of total variation. The total effects are also shown through Table 13 . As reflected, Reactions to Training -> Learning (0.589); Reactions to Training -> Behavioral Changes (0.419) and Reactions to Training -> Results (0.317) are all significant. Further Learning -> Behavioral Changes (0.711) and Learning -> Results (0.539) are also positive and significant. Lastly, Behavioral Changes -> Results. The beta value is high (0.757) and is also positive and significant. Hence hypothesis H7b: Training has a significant impact on results, viz. individual and bank performance for managerial employees has been empirically supported. Thus, on the basis of these results, it can be concluded that the training programs were effective as reflected through all stages of Kirkpatrick model. Till yet, very little research covers gauging effectiveness of training using Kirkpatrick model. This study has set the stage, where the differences at managerial and non-managerial level may be considered to enhance the effectiveness of training.

Overall results highlight that in case of managerial model the R 2 = 0.733 and the adjusted R 2 = 0.732 are higher than that for the non-managerial level with R 2 = 0.573 and adjusted R 2 = 0.571. This indicates that the training is effective for both the managerial level than the non-managerial level, but is more successful for managerial employees.

Discussion and conclusion