- A-Z of Sri Lankan English

- Banyan News Reporters

- Longing and Belonging

- LLRC Archive

- End of war | 5 years on

- 30 Years Ago

- Mediated | Art

- Moving Images

- Remember the Riots

- Site Guidelines

Protecting, Educating and Empowering the Girl Child

on 10/11/2021 10/11/2021

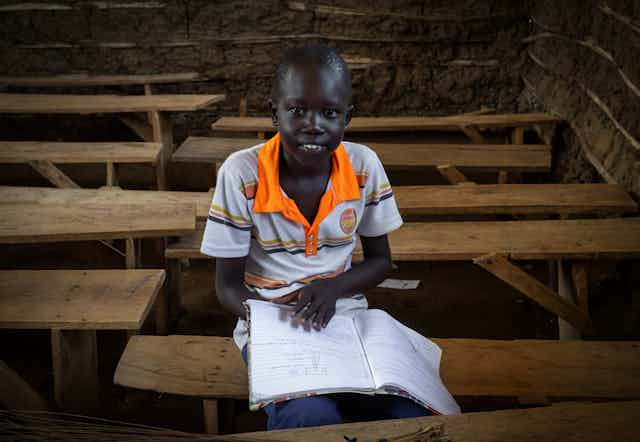

Photo courtesy of Daily Mirror

Today is International Day of the Girl Child

While the lives of young girls in most countries around the world have certainly improved over the past few decades, there are still critical concerns that are unique to girls under the age of 18 such as female infanticide, early marriage and childbirth, Female Genital Mutilation, unequal access to education and health care, stereotyping, teenage pregnancy and sexual abuse. Girls also experience discrimination in food allocation and healthcare.

The World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report (2020) states that gender parity will only be attained in just under 100 years from now.

On December 19, 2011 the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution to declare October 11 as the International Day of the Girl Child to recognize girls’ rights and the unique challenges girls face around the world. The day focuses on the need to promote girls’ empowerment and the fulfilment of their human rights.

“Adolescent girls have the right to a safe, educated, and healthy life, not only during these critical formative years, but also as they mature into women. If effectively supported during the adolescent years, girls have the potential to change the world – both as the empowered girls of today and as tomorrow’s workers, mothers, entrepreneurs, mentors, household heads, and political leaders. An investment in realising the power of adolescent girls upholds their rights today and promises a more equitable and prosperous future, one in which half of humanity is an equal partner in solving the problems of climate change, political conflict, economic growth, disease prevention, and global sustainability,” said the UN.

Although a few girls such as Malala Yousafzai and Greta Thunberg have captured the world’s imagination with their bold and passionate championship of critical causes, young girls are still marginalized and discriminated against, especially in the developing world.

Some 650 million girls and women around the world have been married as children and over 200 million have been subjected to Female Genital Mutilation while 129 million girls are out of school. In developing countries, one out of every four young women have not completed their primary school education.

The lack of education is the most urgent issue because from it stems a host of other barriers facing the girl child. An uneducated girl may be married off early and have children at a young age, endangering her health. She is also more likely to face domestic violence. Without an education, she will be subject to low paying, menial jobs.

“Girls’ education is a strategic development priority. Better educated women tend to be more informed about nutrition and healthcare, have fewer children, marry at a later age, and their children are usually healthier, should they choose to become mothers. They are more likely to participate in the formal labor market and earn higher incomes. All these factors combined can help lift households, communities, and countries out of poverty,” said the World Bank.

But many achievements towards girls’ empowerment and equality are being eroded by the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic; confinement with their families and keeping away from school is increasing early marriages and genital mutilation and is disrupting global efforts to end these practices. It has also resulted in more sexual abuse, including online abuse.

“There is already a worrying rise in abuse, forced marriages, school dropouts, cyberbullying, online sexual violence and female genital mutilation and the Coronavirus pandemic is putting more and more girls at risk,” said the Global Gender Gap report .

Girls are often deprived of the fundamental right to manage their own bodies and consent to sexual intercourse. Worldwide, it is estimated that at least 15 million girls aged 15 to 19 have experienced forced sexual intercourse or other types of sexual abuses during their lives.

In Sri Lanka, the problem of sexual abuse of children is a grave one where 14.4 per cent of late adolescent girls have been subjected to some form of sexual abuse. According to police data there were 10,593 cases of rape between 2010 and 2015, of which three-quarters were statutory rape cases of girls under 16.

Ninety per cent of child sexual abuse cases in Sri Lanka are from incest. This means that perpetrators are close relatives, a neighbour, a religious leader or a teacher.

“After being sexually abused, the girl child is considered soiled and impure, she is marginalized and even ostracized by her community. She becomes the victim twice over, with no form of reprieve,” said Hazel Rajiah-Tetteh, Country Manager of Emerge Lanka Foundation, an organization that works alongside survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Its programme for children comprises of life skills, reproductive health, personal development and entrepreneurship.

“Economic instability, mental health issues, uncertainty and many other factors play into creating an unsafe environment for a child. There is an increased risk of violence towards people and, in this case, children. Children are extremely vulnerable in households that harbor tension, stress and isolation from routine,” said Ms. Rajiah-Tetteh.

“Discussing child sexual abuse has always been difficult and seasonal due to the stigma and sensitivity attached to it. We do however see that people speak up and about it more often now. This awareness may play a key role in cases being reported more often,” she added.

Taking into account the rise in reported numbers on child abuse, as well as the pandemic climate where the risk has increased for child safety, Emerge has launched a project to keep children safe. #ProtectEveryChild is an online awareness campaign built to educate the public on childhood sexual abuse, its impact, indicators, ways to report cases, ways to be active in child protection and create a wave of solidarity online, for individuals to take accountability, responsibility and make an active pledge to “be alert, speak up, and to always Protect Every Child”.

To mark #DayOfTheGirl , Groundviews spoke to @EmergeGlobal Country Manager Hazel Rajiah on the worrying rise in sexual abuse in #SriLanka , its associated stigmas, and the role communities need to take on to protect our children. To read our article, see: https://t.co/aC8kEMIIdY pic.twitter.com/4m2gqHsAKy — Groundviews (@groundviews) October 11, 2021

Related Articles

Re-inventing the idea of university: response to professor jayadeva uyangoda part 2, re-inventing the idea of university: response to professor jayadeva uyangoda part 1, re-inventing the idea of university: some reflections and proposals, understanding the gender gap in the workforce, religious indoctrination violates children’s rights, mainstreaming education for children with disabilities, love for saree or fear of change, gotagogama: a learning curve, life after this death, a failed government is destroying our children.

Empowering girls and communities through quality education

Meet these adolescent girls and young women achieving their dreams through education, and the parents and community members supporting their education and empowerment in Mali, Nepal, and the United Republic of Tanzania.

These individuals have been part of the Joint Programme on Empowering Adolescent Girls and Young Women through Education . Grounded in the collective commitment of UNESCO, UN Women and UNFPA, the Joint Programme applies a coordinated and multi-sectoral approach to empower girls and young women through quality education.

First stop, Mali

In Mali, over 5,600 out-of-school girls and young women were empowered through literacy and vocational training, and learned about sexual and reproductive health. Some 200,000 community members were also sensitised on girls’ retention, re-entry and access to education and 3,560 teachers, school administrators, parents and community leaders benefitted from trainings to foster inclusive and safe learning environments for girls in schools. School-age girls and boys who were displaced due to inter-communal conflict have also been re-integrated into the formal school system.

Adama, a bright learner from Mopti

“I like learning”, says Adama. “My first language is Fulfulde but I also can speak Bambara. I learned this language with my classmates at school.”

Adama, aged 11, was forced to leave her hometown with her family to flee from inter-communal conflict between the Peul and Dogon ethnic groups in Mopti, central region of Mali. She and her family are living in a refugee camp on the outskirts of Bamako.

“An educated person is more important than an illiterate one”, says Aminata, Adama’s mother. “I want her to study and get a good job after she finishes school.”

Adama had the chance to return to school through the joint efforts of UNESCO, UNFPA and UN Women to re-integrate internally displaced children into the formal school system in Bamako. At school, Adama learned to read and write in French, speak Bambara, the local language used in Bamako, and even made new friends.

When schools closed to contain the spread of COVID-19, Adama could not continue learning because she didn’t have access to the internet and had to focus on household chores. The Joint Programme enabled students like Adama to continue learning with refresher courses that were disseminated on the national television channel.

Adama has since returned to school. However, schools and access to education remain threatened by the ongoing conflict. Adama urges political leaders to do all they can to end the civil war so that she and her family can return to their hometown, and to ensure that girls like herself are able to continue their education.

Next stop, Nepal

In Nepal, the Joint Programme worked across 5 districts and with 14 municipalities. Over 6,300 girls and young women came together in community learning centres or local resource hubs that foster education and livelihood for marginalised groups. Out of these girls, 1,874 participated in functional literacy classes integrating comprehensive sexuality education and mother tongue-based multilingual education to ensure an inclusive and equitable education. Nearly 4,470 girls and young women also participated in vocational skills courses, out of which 1,458 started generating an income.

Chanda, a champion for girls from Rautahat

“Pregnancy at a young age has huge costs on girls’ reproductive and psychological health. And they are subjected to gender-based violence”, says Chanda. “We must empower girls to speak out for their own rights and well-being. That’s why I will continue to work in education.”

Chanda, aged 23, had dropped out of school when she engaged with the Joint Programme and received vocational training. She was inspired to pursue a career in education while working as a facilitator for the UNESCO-led functional literacy classes.

Chanda works with girls who dropped out of school, girls who have never been to school, and girls who married young. “Child brides are denied further education, lack literacy, and are unable to manage their finances, making them completely dependent on others”, says Chanda. She believes that efforts to uplift girls and women must complement efforts to reduce early marriage.

Chanda has been able to follow girls’ progress after their participation in the classes. She noticed incredible improvement in their confidence stemming from their participation and learning. However, the lockdowns throughout the pandemic resulted in many girls returning to farm work and parents taking advantage of lower dowries to marry their daughters. There is still much progress to be made to change the attitudes of parents and guardians towards their daughters.

Despite these challenges, Chanda is committed to working with adolescent girls to inspire them and change social attitudes towards girls’ education.

Dhauli, an entrepreneur and role-model from Bajura

“I couldn’t even recite the alphabet before I took the classes. Now I have the confidence to speak at workshops”, says Dhauli. “Education is important – without the trainings I received, I couldn’t have started my own enterprises.”

Dhauli was married at age 12 when her mother died, so she never had the opportunity to go to school. She attended the Joint Programme’s functional literacy classes, through which she developed entrepreneurship skills.

Since joining the classes, Dhauli started a grocery shop and runs a farm. She has already taken out NPR 400,000 (US$ 3,300) in bank loans to invest in her shop and the investment has paid off. She currently earns up to 4,500 NPR (US$ 37) each day. She has also been able to expand her family farm by purchasing buffalos and pigs.

Dhauli is the first person in her family to be financially literate. She is inspiring her peers through entrepreneurship skills and extending her knowledge to her husband and children. For Dhauli, the freedom of running her own business is also tied to securing a future for her daughters.

“I didn’t get to study but with my earnings, I can make sure that my daughters will get an education”, she says. “This must improve our future. I may have been an illiterate woman, but my daughters will not be.”

Komal, an advocate for girls’ education from Rajpur Farhadawa

“I used to think that I was a poor student, but now I know that I am a good student and can do well”, says Komal. The functional literacy classes have improved my life. I am confident that I will do well in the future.”

Komal, aged 15, dropped out of school by the time she was in grade 6 because of frequent teacher absences and low engagement. However, two years later, she took part in the classes and was inspired to go back to school as she discovered the value of her education.

Komal learned how to advocate for her own education, how to recognize and report gender-based violence, and how to pay attention to her own reproductive health and address health concerns. She even learned about sexual exploitation and human trafficking, and how to protect herself.

Komal also participated in a radio programme organized by UNESCO where she interacted with local leaders and stakeholders from her district. She discussed health, education and issues affecting youth with them. The experience boosted her confidence and helped her overcome her fear of public speaking.

Komal was empowered through the Joint Programme and inspired to pursue a future advocating for girls’ education. “I believe that all girls should have an education”, she says. “I want to be involved in similar programmes in the future so that I can motivate other girls to study.”

Parbati, an FLC facilitator from Simalkot

“To watch them learn to read and write before my own eyes – that filled me with pride and satisfaction”, says Parbati, a facilitator for the Joint Programme’s functional literacy classes and youth advocacy coordinator from Simalkot. “I realized how important education is in showing people their potential.”

When Parbati began teaching the classes, she noticed that the women who attended the trainings lacked the literacy skills needed to sign their own names. As she taught them the Nepali alphabet and numeracy skills, she noticed they gained interest in learning even more. Parbati helped the women gain a sense of pride as they no longer had to sign official documents with a thumbprint.

Parbati also organized interactive sessions with learners in Achham, where she discussed pregnancy, family planning and menstrual hygiene. She advocates for ending harmful practices, including sexual harassment, violence against women and girls and early marriage.

Teaching literacy to women has been especially rewarding for her as a facilitator as she has witnessed the transformation of women from learners to entrepreneurs. Beyond literacy, the functional literacy classes teach women about organizing savings and investment groups. Many of the women started their own businesses.

Parbati noticed that the women of Simalkot are excelling in the classes and asking for more educational opportunities. “If they have come this far after one round of training, imagine what they can achieve with more.”

Ratan, a transformed mother from Duni

“The first day attending the class was one of the happiest days of my life”, says Ratan. “I wanted to continue my education to secure a good future for my child. I have to be a good example for my daughter.”

Ratan, then in grade 6, was forced to drop out of school because she was arranged to be married. She became a mother at age 21 and cared for her family. Ratan’s options were limited, as engaging in public activities outside of the home is often stigmatised according to social customs in the Sudurpashchim Province of Nepal.

After convincing her family, Ratan attended the functional literacy classes held under the Joint Programme. “At first, she was too shy and nervous to introduce herself in the class, but now, she can speak her mind in front of a crowd”, says Saraswoti, Ratan’s facilitator.

Ratan gained confidence as her literacy skills improved and she learned about family planning, reproductive health and hygiene, and harmful cultural practices. Ratan often shares her new knowledge, especially about reproductive health and hygiene, with women in her community. She has now found a greater sense of independence in life.

Before the training, Ratan lacked the skills to access her own bank account and withdraw money sent by her husband who is a migrant worker in India. Now, Ratan is financially literate, capable of accessing her own bank account, making withdrawals and deposits and organizing her family’s finances.

Last stop, Tanzania

In Tanzania, the Joint Programme reached girls and young women in remote areas where access to learning can be more limited. To prevent violence against girls and increase the retention of girls in school, 40 primary and 20 secondary schools across 4 districts now provide counselling services through 112 youth clubs. Out-of-school girls and young mothers were provided with vocational, literacy, numeracy as well as sexual and reproductive health programmes. Over 4,000 in-school and 1,000 out-of-school girls and young women benefited from quality educational opportunities. Over 180 local government officials, 440 teachers and 60 curriculum developers from higher learning institutions were trained on gender-responsive pedagogy, life skills, sexual and reproductive health, HIV and AIDS, and gender-based violence (GBV).

Fatma, a businesswoman from Mkoani

“When I dropped out of school, I could not even read full sentences. With the support from the Joint Programme, I gained the confidence to read, write and do basic mathematics. I now help other girls to learn how to read and write”, says Fatma, a businesswoman aged 25 from Mkoani.

Fatma dropped out of school like many girls and young women in Tanzania. Soon after, she was married and had three children. She felt like her dreams had ended when her education stopped at the age of 14. Life prospects are limited for girls and young mothers in Tanzania without an education, or the knowledge and skills for employment.

Fatma joined a community-based youth centre established by the Joint Programme, where she was taught basic literacy and numeracy. She also learned digital skills at the centre using a tablet and a smartphone provided by the Joint Programme to access other learning materials and build her entrepreneurship and vocational skills. She developed business management, accounting and communication skills.

Fatma is now pursuing her dreams. She opened a small grocery shop with the income she received for her work as a henna artist. She learned henna painting at the vocational training held under the Joint Programme. “I sell rice, sugar and some vegetables. It is such a big achievement being economically independent with my own income. My husband is supportive of my work.”

Fatma also provides guidance to young women in her community, sharing her own experience. “I helped my peers learn how to run a business. One of my friends also started her own business as a henna artist and a tailor.”

Ashura, an entrepreneur and role model from Kasulu

"People in the village no longer see me and other girls who dropped out as failures but see us as people leading our lives autonomously", says Ashura, an entrepreneur from Kasulu.

Ashura, a young mother now aged 22, could not continue learning after primary school due to her family's financial challenges. Girls and young mothers who drop out of school in Tanzania often take up household chores and are left behind from education. Without alternative learning opportunities and access to financial services, they are prevented from earning incomes and living autonomous lives.

When Ashura received entrepreneurship training and opportunities from the Joint Programme, she discovered how to run a small business making and selling products such as soap, batik and nutrition flour. She also learned how to apply for loans allocated to women’s groups by the District Council.

Starting out with seed money, Ashura increased her cash flow by selling sugarcane and rice. Together with a group of young women who had also benefited from the Joint Programme, Ashura formed an income-generating group to encourage women-led economic activities. Their financing model extended to the formation of a village community banking (or VICOBA).

VICOBA is particularly helpful when the existing social services are insufficient. "Each member of the group contributes 5,000-10,000 TZS (US$ 2-4) every two weeks. VICOBA money is like an insurance or a loan given to group members for any emergency needs", says Ashura.

As her life changed, Ashura noticed a change in the perception of community members vis-a-vis out-of-school girls, who were previously seen as failures and are now looked up to as role models in their community.

Rahma, a confident learner from Kasulu

“Through the Safe Space-TUSEME club, I gained the confidence to speak out to my friends, teachers and parents”, says Rahma, a grade 10 student. “I was motivated to study hard. That was why I passed the national exam with a good score.”

In Tanzania, only 69% of girls transition from primary to lower secondary education compared to 73% of boys, according to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (2017). This is attributed to less support from the family, lack of confidence, gender-based violence (GBV) and adolescent pregnancy.

Rahma, aged 15, joined the Safe Space-TUSEME (‘Let’s speak out’ in Swahili) club established by the Joint Programme in her school. There, she learned about gender equality and GBV, where to report cases of GBV or seek guidance and counselling, and how to undertake collective action if faced with a GBV incident. Youth-led activities such as drama and poetry and advocacy with parents and teachers about the challenges faced by girls at school helped transform attitudes around girls’ education.

Encouraged through the club activities, Rahma successfully transitioned to secondary school with excellent exam results. Her relationship with her parents also changed positively: “Housework was considered only for girls. However, my parents don’t think like that anymore. They are encouraging me to study. They were delighted when I passed the national exam”, says Rahma.

Now, Rahma continues to take part in the Safe Space-TUSEME activities in her secondary school. Her club conducts campaigns to keep girls safe from adolescent pregnancy. “A night market is a common place where girls can be more vulnerable to adolescent pregnancy. With ongoing campaigns, now I see fewer friends are joining night markets”, says Rahma. She hopes other schools establish Safe Space-TUSEME clubs to support more girls to pursue their education. “I want to help other girls gain confidence.”

Warda, an ICT facilitator from Mkoani

"We can teach girls how to read and write and acquire vocational skills so that they can be financially independent. I hope that more girls gain confidence, leadership, independence, higher income and are safe from violence. I believe empowering women is empowering society", says Warda, a young woman from Mkoani.

Warda was unemployed after graduating from college. She joined an ICT lab established by the Joint Programme as a facilitator. Through this role, she acquired teaching skills for literacy, numeracy and entrepreneurship using tablets. More than 200 out-of-school girls and young mothers in Mkoani learned business management, accounting and communications skills as part of the ICT lab.

One of Warda’s students, Zuhura, did not know how to read and write but learned through a self-learning application on a tablet. Now she runs a small business selling pillows and teaching other girls how to read and write and gain other basic entrepreneurial skills. Warda also created an income-generating group together with her students called the 'Women Association for Community Development Strategies', enabling the group to raise funds and sustain business ventures.

Girls who learned about entrepreneurship through the course at the ICT lab felt empowered, but empowerment was not limited to learners. "I gained the confidence to teach adults from any background. I am delighted to see their transformation as well as mine", says Warda.

She is currently empowering more out-of-school girls while following a Master's course. Recently, she also started a part-time job in the Mkoani district office. She dreams of expanding this initiative to other districts in Pemba, Unguja Island and even the Tanzania mainland.

Angel, a science wiz from Sengerema

"I told myself, 'Angel, you will not fail'. I became number one in physics and moved to upper secondary school", says Angel, aged 17. “I believe girls can do as well as boys in sciences.”

In Tanzania, poor pedagogical practices have led to discrimination and girls' lower performance than boys, especially in mathematics and science subjects in national examinations during the past five years. It is one of the reasons hindering the transition of girls from secondary to upper secondary education.

Teachers at Angel's secondary school received a Joint Programme training on gender-responsive pedagogy to counter stereotypes and socio-cultural bias reinforcing the notion that science subjects are not only for boys and difficult for girls.

With support from her teacher, Angel's performance in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) subjects improved. She achieved excellent scores in her national exams in biology among other subjects. She became the best female student within her school and was selected to focus her studies on physics, chemistry and biology.

Angel inspires other girls in her secondary school to study hard including in STEM subjects and to pass the national examination. Four of Angel's peers also successfully transitioned to upper secondary school. Angel also brought a positive influence home. Her parents are proud of her achievements at school and support her education.

Safia, a woman leader from Pemba

"Through the Joint Programme, more community members encourage the education of girls and boys, while discouraging early marriage and unintended pregnancy. It was helpful to persuade the government offices to establish a secondary school in our community", says Safia.

Safia is a community leader in Pemba island. She is one of five women leaders in 143 shehias (or wards) in the region, "Being a woman leader can be challenging, but my community members are very supportive", says Safia.

Safia became a champion for girls’ right to education through the Joint Programme. She and other community members developed dramas to engage her community to invest in girls’ education. They raised awareness among other community members about preventing early marriage and providing needed support for girls to continue their education. Since then, the number of girls transitioning to secondary education in her shehia increased from 5 to 15 girls.

Safia also advocated for the construction of the first secondary school for girls and boys in her shehia. Students used to go to neighbouring shehias to attend a secondary school. "It is very tough for students to transition to secondary education when there isn’t a secondary school in our community. Imagine girls taking boats to reach a secondary school in different shehias. It takes around 2 hours", says Safia.

"I expect more girls to continue schooling at the secondary school in our shehia. I hope that they will become women leaders like me when they grow up", says Safia.

Almachius, a community leader from Kasulu

"Through the Joint Programme activities, adolescent girls and young women became more empowered. Parents and community members, ward and district officers witnessed their growth. In return, they started to expand their support", says Almachius, a focal point for the Joint Programme in the Kasulu District Council.

Almachius has observed many positive achievements in the district. One of them is a loan from the District Council of 9,000,000 TZS (US$ 3,900), awarded to three women-led income-generating groups created by the Joint Programme. And in Heru Ushingo, the girls' transition rate from primary to secondary education has increased from 85% in 2017 to 99% in 2020 since the Joint Programme was initiated.

Also, 7 out of 15 schools in Kasulu have built more classrooms, toilets, water facilities and changing rooms for menstruation after trainings held by the Joint Programme on water, sanitation and hygiene. "It was possible because parents and community members who participated in the trainings donated bricks and volunteered to build school facilities. The Titye secondary school is even building a science, technology, engineering and mathematics laboratory", says Almachius.

As a result of this work, early marriage and unintended pregnancy rates have decreased. "Harmful social practices and gender-based violence decreased while reporting cases increased", says Almachius. The ward and district offices and schools worked closely with the Joint Programme to reinforce reporting mechanisms.

Almachius hopes to scale up this work to other wards in Kasulu. Six additional wards in Kasulu are already replicating the Joint Programme interventions to promote girls’ empowerment through education.

Related items

- Gender equality

- International Women’s Day

Other recent stories

- Login/Sign up

- CHAPTER 1 Introduction

- CHAPTER 2 Types of education

- CHAPTER 3 Importance of education

- CHAPTER 4 Early Childhood Education

- CHAPTER 5 Education system in India

- CHAPTER 6 Girl Child Education in India

- CHAPTER 7 Role of the civil society in the education sector

- CHAPTER 8 About Oxfam India

- CHAPTER 9 Role of Oxfam India in girl child education

- CHAPTER 10 Why donate to Oxfam India

Importance of Girl Child Education

Empowering girls through education.

Everyone wishes to see this world become a better place and strives to do their bit to change the world. But often we find it difficult to find a cause we want to support and the organization we would like to donate to.

Here we will explore the issue of quality and affordable education, which can help you understand why it is one of the most pressing issues and how you can sponsor child education in India. It will also help you understand.

Oxfam India’s work in education and how you can support Oxfam India to educate a child.

What You Will Know About Girl Child Education in This Resource

To help you read on all specific topics, we've put together an interactive table of contents. Click each link to be jumped to different sections. (Or, you can also scroll down and start from the beginning.)

- Definition of Education

- Types of Education

- Importance of Education

- Early Childhood Education

- Education System in India

- Girl Child Education in India

- Role of the Civil Society in the Education Sector

- About Oxfam India

- Role of Oxfam India in Girl Child Education

- Donate to Oxfam India

What is education? Is there a difference between education and schooling? In this chapter we will learn what is the meaning of education and the concept of education.

What is education?

Education definition.

The term ‘Education’ originated from the Latin word ‘Educare’, which means ‘to bring up’ or ‘to nourish’. Another Latin word ‘Educatum’ gave birth to the English term ‘Education’. ‘Educatum’ means ‘the art of teaching’ or training.

Oxford dictionary defines education as, “a process of teaching, training, and learning, especially in schools or colleges, to improve knowledge and develop skills.” It is the action or process of being educated.

Concept of education

Most of us, when we think of education, we imagine a formal school, with students learning subjects like Mathematics, English Literature, Social Studies, Physics, Chemistry, or Biology. We imagine a school where students play sports in their free time and are regularly assessed through exams. But is education only confined to a school or university building? Can a child, or even an adult learn outside of school and improve their knowledge and skills?

Education is the process of acquisition of knowledge and experiences, and development of skills and attitudes of an individual, which help them lead a fruitful life and contribute to the development of the society. The main purpose of education is the all-round development of individuals. Education aims to not only focus on skill development, but also on personality development to help individuals become socially responsible citizens of a country.

What is value education?

Value education aims to develop certain attitudes in individuals so they are able to face different situations in life. It is often wrongly assumed that value education teaches values. Value education does not teach values but develops the ability to find one’s own values. Individuals are encouraged to develop critical thinking so they can deal with conflicts, understand their actions and their consequences, develop healthy relationships, and become dependable members of the society.

https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/american_english/education

Education goes beyond the four walls of a classroom. A child continues to learn throughout their life, even during adulthood, through different experiences. Different types of education, gives different types of learnings.

How many types of education are there

There are three main types of education. In this chapter, we will learn the different types of education, their examples, characteristics, advantages, and disadvantages.

What are the three types of education

The types of education are: Formal Education, Informal Education, and Non-formal Education.

1. What is Formal Education

Formal Education refers to the education imparted to students in an established educational institute premises by trained teachers. The teachers must have a certain level of training in the art of education and knowledge of relevant subjects.

Students are taught basic academic skills based on a certain syllabus. Regular assessments of learning outcomes are conducted through examinations. There is a set of established rules which both teachers and students follow in order to complete formal education.

Formal education begins at the elementary/primary level, continues through high school and college or university. Children often attend nursery or kindergarten before beginning their formal education.

What is primary education

Formal education begins with primary education, also called elementary education. Primary education begins in kindergarten and lasts till the sixth grade. Depending on the specific education system, primary education may even begin from class 1 till class 4 – class 7. Primary education helps children develop the ability to learn and understand the rules of formal education.

What are the examples of Formal Education

- Classroom instructions or training

- Grading and certification in school, colleges, and university

- Set subjects and syllabus

What are the characteristics of Formal Education

- Structured hierarchy

- Strict rules and discipline

- Regular fee

- Grading system

- Formal teacher-student relationship

What are the advantages of Formal Education

- Structured and organised

- Trained professionals as teachers

- Regular assessments to enable students to reach higher levels

- Recognised certification

- Better access to employment

What are the disadvantages of Formal Education

- Rigid and lacks flexibility for students to pursue their own interest

- Too much importance to grades puts extreme pressure on those with average scores

- Fails to recognize non-academic talents in students

- Set syllabus limits the scope of learning

- High expenses

2. What is Informal Education

Unlike Formal Education, Informal Education is not imparted in school, college or university. It is not deliberate, does not follow a set syllabus and timetable, and there are no regular assessments. There is no structured teacher-student relationship.

Informal Education is imparted by parents to their children, one person to another. Children learning how to ride a bicycle from their parents, one individual teaching another how to bake are examples of informal education.

Informal Education is also conducted through reading books, or online material. It is also the education obtained in one’s surroundings, in their daily lives, like in a marketplace, or by simply living in a community. Individuals who join some community groups and learning occurs during their activities, or take up some project of their own and learn themselves, are also considered to be acquiring informal education.

What are the examples of Informal Education

- Spontaneous learning – a person learns how to use an automatic ticket vending machine

- Parents teaching their children certain skills

- Individuals taking up a sport activity on their own

- Learning a psychological fact by reading a website article

What are the characteristics of Informal Education

- It is spontaneous

- Happens outside the formal classroom

- Life-long process

- No structured syllabus

- No grading system for what one learns

What are the advantages of Informal Education

- More flexible as individual have the advantage to choose what they wish to learn

- Individuals have the opportunity to learn the skills not taught in formal education

- Utilizes a variety of means – TV, internet, conversations, magazines

- Learners are more motivated as they have flexibility

- Less costly

- Flexible time

What are the disadvantages of Informal Education

- Lack of discipline or rules may lead to inconsistency

- Information acquired through internet or conversations may not be reliable

- No set timelines or schedule

- Difficult to recognize

3. What is Non-formal Education

Non-formal Education is organised education outside the formal school/university system. It is often referred to as adult education, adult literacy education, or community education. Non-formal education is conducted by community groups, government schemes, or an institute. It can also be conducted as home education or distance learning.

Non-formal education may not have a set syllabus or curriculum. It focuses on the development of job skills, develop reading and writing skills in out of school children or illiterate adults. Non-formal education system may also be used to bring out-of-school children at par with those in formal education system.

This system does not have a specific target group and does not necessarily conduct examinations. Children, youth, and adults can be a part of this system.

What are the examples of Non-formal Education

- Community based adult education programmes

- Community based sports programmes for children

- Fitness programmes by private institutes

- Computer and language courses in a community

- Online courses

What are the characteristics of Non-formal Education

- Has a flexible curriculum

- There is no age or time limit

- One can earn while learning

- Examinations may not be necessarily conducted

- May not require certification

- Involves vocational learning

What are the advantages of Non-formal Education

- Flexibility of age and time

- Freedom to pursue one’s interest and choose a programme

- No need of regular exams or grades

- Helps in learning useful job skills

What are the disadvantages of Non-formal Education

- Lack of certificates may leave a skill unrecognized

- Students may be irregular due to the lack of set regulations

- Untrained teachers

- Basic reading and writing skills may still be required

- Lack of formal structure and rules may lead to students discontinuing

In this chapter, we will learn about the importance of education, early childhood education and the impact of lack of education.

Why education is important

Now that we know what are the different types of education, let us explore the importance of education in life.

Education is a human right. Education is important for not only a holistic development of an individual, but the society as well. 59 million children and 65 million adolescents are out of school, across the world, and more than 120 million children do not complete primary education.

Lack of education hampers an individual from reaching their full potential. Out of school children miss out the opportunity to develop their skills and to join the work force later in their adult life. Unemployment further creates more stress among people, especially the youth, leading to social unrest and crimes, adversely impacting the development of a country. Hence, education is the key to an individual’s and a country’s development. Learn more about illiteracy in India.

All the different types of education enable an individual develop cognitive skills, emotional intelligence, and skills required to be employed.

Education helps an individual develop the ability to think critically, understand the people around them and their surroundings, make informed decisions, and understand the consequences of their actions on themselves and others. Education is necessary for an individual to live a fruitful life and become a responsible member of the society.

Education must begin early in an individual’s life, during early childhood. This is the time when important brain development occurs. In the next chapter we will explore early childhood education more in depth. Let us first understand the importance of education in an individual’s life and the importance of education for a country.

Why is education important for an individual

As already discussed, education helps an individual develop cognitive skills and emotional intelligence. An uneducated person, who doesn’t understand themselves, who cannot understand how to interact with people around them, is isolated from their society.

Humans are social beings and need to form healthy relationships with their fellow humans and live with them in harmony, in order to survive. Lack of education, hampers a person’s ability to understand other people’s emotions and cannot understand their own emotions to be able to form a relationship. Additionally, education helps individuals combat diseases, change regressive social norms, and promote peace.

Further, an individual who does not attend school, or take any form of formal education, cannot develop the skills required to enter the workforce, and is eventually pushed into poverty.

Why is education important for a country

Education is the key to economic development. It reduces poverty, boosts economic growth, by ensuring people enter the work force and increase their income.

Education helps promote stability in times of conflict and crisis. Children are forced out of school in a conflict situation, leading to high drop-out rates. The chance of education lays a path to normalcy for children. Girl child education, especially, benefits a country. Educated women can make informed decisions, reduce gender violence, have fewer children, and join the work force. It is the first stepping stones towards ending gender based discrimination and inequality. This village in Uttar Pradesh has an inspiring story of changing regressive social norms through education.

In this chapter, we will learn what is early childhood and the importance of early childhood education.

What is an early childhood

Early childhood is the period from birth to eight years of age. These are the most critical years in a child’s life. During this time the brain is at its peak development stage and determine a child’s development over the course of their lives.

This is period is extremely crucial because children develop cognitive, physical, social, and emotional skills. They are highly influenced by their environment and require utmost care by parents and community members to ensure holistic development. Hence, the emphasis on early childhood education.

What is early childhood education?

Early childhood education is not only preparation for primary school, it also aims to develop basic life skills in children to lay a foundation of lifelong learning and success. It consists of varied activities to aid in the cognitive and social development of children before they start preschool.

It consists of both formal and informal education. Parents are considered to be the first ones educating a child, as a child develops their first relationship with parents. This relationship can have a significant impact on child development and early childhood education. This stage of early childhood care and education typically starts between 0 to 2 years of age.

After this stage, formal education starts. Formal education for early childhood may vary from state to state, a child’s age and their learning abilities. Early childhood education programmes may vary for each age group and run at different levels – nursery, playgroup, preschool, and kindergarten.

Why is early childhood education important?

A child’s brain is at its peak developmental stage from 0 to 8 years of age. Their experiences lay the foundation of a child’s emotional, cognitive, and physical development. Following are some of the benefits of early childhood education:

Social skills

Humans are social beings. They need to develop healthy relationships in order to live a fruitful life. Early childhood education ensures children learn how to socialize with other children of their age, with people outside of their immediate family and develop the skills to successfully socialize with people later on in their lives.

Sharing with others is the core of any relationship and peaceful society. Early childhood education enables a child to learn how to share their things so they can develop strong friendships with other children.

Team working skill is one of the most important assets of an individual’s holistic development. The skill is useful throughout formal education, in personal relationships, and in the workforce. Hence, it is crucial to ensure that children develop skills early in their childhood.

A child cannot be educated if they do not have the enthusiasm and curiosity to learn new things. Early childhood education programmes ensure that children develop the curiosity to learn.

What are early childhood education programmes

Several organisations in India, public, private, and non-governmental sectors provide early childhood education programmes. Below are early child education programmes in India, across different sectors:

Government organisations

The Ministry of Women and Child Development (MWCD) plays a key role in providing early childhood education in India. The ministry has set up Anganwadi centres (courtyard shelters) across rural areas to provide health, nutrition, and education to children from minority groups and economically weak groups. The government has facilitated the transition of children from preschool to elementary school, by relocating the Anganwadi centres close to elementary schools and aligning their schedule with those of elementary schools.

Non-government organisations

In India, non-government organisations have an important role in filling the gaps left by the government. NGOs working for education provide early childhood care and child education to marginalised children. As per government estimates, NGOs run child education programmes have provided education to 3 to 20 million children in India. The programmes include direct intervention in areas where there are no government programmes or to improve the quality of government programmes. Oxfam India works with a network of grassroot partners across six states in India, to facilitate education, especially girl child education, and advocates for increased government spending in the public education system. Oxfam India and one of its partner, Lokmitra, run this small school in Raebareily which attracts students from private school as well.

Private Institutes

India has seen a rapid rise in private institutions at all levels of education. As per government estimates, around 10 million children have participated in early child education programmes run by private organisations. Some organisations provide only early childhood care and education, while others may run till elementary school and/or higher secondary school level. Private schools, however, charge exorbitant fee, leaving millions of children out of the education system.

Early childhood education in India

According to Census 2011, there are 164.48 million (approximately 16.5 crores), children from 0 to 6 years of age in India. [6] These numbers indicate a strong need for efficient early childhood education programmes in India. Constitutional and policy provisions have been made to ensure early childhood education in India.

Article 21A of the Indian Constitution, provides for the right to free and compulsory education for children from 6 to 14 years of age, in purview of the Right to Education Act (RTE) (2009). Article 45 urges the state government to provide Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) to all children till the age of six years.

The Right to Education Act, guarantees children the right to free education, whereas, ECCE is not stated as a compulsory provision. The RTE states to provide free pre-school education for children above three years. In 2013, the Government of India approved the National Early Childhood Care and Education Policy. [7]

The policy promotes free, universal, inclusive, equitable, joyful, and contextualised opportunities for laying foundation and attaining full potential for all children below 6 years of age. [8] It aims to promote a holistic development of children in the said age group. The policy is a key milestone in filling the gap in early childhood care and development in India and strengthening elementary education.

https://www.educationforallinindia.com/early-childhood-care-and-education-in-india-1.pdf - National University of Education Planning and Administration – New Delhi - page 26

- https://unicef.in/Whatwedo/40/Early-Childhood-Education

https://wcd.nic.in/sites/default/files/national_ecce_curr_framework_final_03022014%20%282%29.pdf

Education in India is provided by public and private schools. The most important element of the education system in India, is the Right to Free and Compulsory Education Act, (RTE). RTE constitutionally guarantees education as a fundamental right of every child in the age group of 6 to 14 years.

Despite the provision, there are more than 60 lakh children out of school in India. [10]

In this chapter, we will understand the provisions laid down by the RTE and the gaps in its implementation.

What is Right to Education Act

The RTE Act (2009) lays down legal provisions to grant every child aged between six to fourteen years, the right to free and compulsory elementary education of an appropriate standard in a neighbourhood school. Here are some interesting facts about RTE.

Education is a concurrent subject in which both the Centre and the states play a role. It is necessary for the states to draft rules to implement the provisions laid down in the RTE, with reference to the framework provided by the Centre. The states can modify the rules to suit their local needs. However, implementation of RTE has greatly varied across the states. [11]

India continues to fail to spend the financial resources required to meet the minimal norms under the RTE Act. Bihar, for instance, spends only 30% of what is needed to implement the Act in totality – enrolling all children in school, hiring the minimum number of required teachers, improving infrastructure, and providing learning materials. Additionally, Bihar is also failing its children from minority groups.

Hardly 12.7% of schools in India comply with the minimum norms laid down under the RTE Act. There are wide gaps in RTE implementation between different states; ranging from 39% in Gujarat, to less than 1% in Nagaland, Sikkim, Meghalaya, Tripura, and Lakshadweep. 70% of teachers in Meghalaya lack the required qualifications. [12]

The RTE Act, Section 12(1)(c) envisions that schools must provide spaces for the economically weaker section of the society so that children from different backgrounds have equal opportunities and that will help build a more equal society. Studies show that giving opportunities to students from different economic backgrounds, makes student more social, generous and egalitarian, and they are less likely to discriminate against poor children. But instead, private schools create hurdles for children with disabilities and those from marginalised communities to avoid their enrolment.

India’s government spending on education has stayed below 4%, despite successive governments’ electoral commitment to spend 6% of its GDP on education. The government discriminates in the allocation of the education budget. For instance, in government-run Kendriya Vidyalaya and Navodaya Schools, government spending is roughly around Rs. 27,000 and Rs. 85,000 per student, respectively. However, the spending in regular government schools is just over Rs. 3000 per student per year. [13] Without equitable investment in public schools, inclusive education cannot be achieved. This one of a kind satellite school in East Delhi imparts education with no desks, walls, or chairs.

The inefficient implementation of the RTE Act, is a classic example of the gaps between policy and its implementation. There are limited efforts in building awareness of the provisions of the act, the need of such an Act; among those on the ground responsible for its implementation and those for whom the Act is. [14]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_7WspAXyK5Y Is the government spending enough on education? Our Social Policy Researcher, Kumar Rajesh explains the reality behind the government’s claim of spending 4% of the GDP on education.

Privatization of education in India

In light of the gap left by the government in the education system in India, private schools are growing in huge numbers. However, the increasing rise in private schools is socially segregating children of rich and poor families in India. Financially better off families send their children to private schools, with better facilities and smaller classes, thus widening the economic and social gap in an already unequal society.

Between 2010-11 and 2015-16, the number of students enrolling in government schools across 20 states fell by 13 million, while 17.5 million new students joined private schools. [15] Private schools are further unregulated and many of them do not meet the basic standards of infrastructure, safety, and quality of education. However, the condition of public schools is forcing even the poor families in India to enroll their children in private schools, leading to huge financial burden on families. Thus, rendering education in India a privilege, instead of rendering by class and caste.

Even though, the enrolment in government schools is declining they remain the main provider of elementary education in India, accounting for 73.1% elementary school and 58.6% of the total enrolment. [16] India still needs to universalize its education system, by providing better quality public education institutes.

What are the problems in the education system in India [17]

- Lack of a clear definition of an out of school child is a grave concern. Without a clear definition to identify when a child stops going to school and becomes a drop-out, it is difficult to enroll and retain children in school.

- There is ambiguity about specific roles the School Management Committee (SMCs) have to play. The SMCs are not aware of their responsibilities or the members themselves do not know that they are a part of the SMC. A research by a leading non-profit Pratham based in Delhi in 2013 found that only 10 per cent of the SMC parent members interviewed were aware that they were part of the SMCs. [18]

- The SMCs have the mandate to prepare School Development Plans (SDPs), but this is hardly followed in practice. Capacity building programmes for SMCs, to enable them to follow their mandates are not being implemented thus affecting their functioning. [19]

- The RTE Act implies to both public and private schools, but its implementation in private school remains weak. Private schools are on the rise, and they deliberately omit the rule of the RTE, while most government schools struggle to implement because of lack of resources.

- The RTE Act provides for a mechanism to ensure the availability of qualified teachers by setting up teacher training institutions. Some states have completely omitted the provision to set up training institutes.

[9] https://www.oxfamindia.org/sites/default/files/2019-02/Davos%20India%20Supplement.pdf

[10] https://mhrd.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/upload_document/National-Survey-Estimation-School-Children-Draft-Report.pdf (2014) - pg 9

[11] Federalism and Fidelity – RTE Review (2014) – Oxfam India

[12] https://www.oxfamindia.org/sites/default/files/2019-02/Davos%20India%20Supplement.pdf

[13] https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/education/Government-spends-Rs-85000-on-each-Navodaya-student-annually/articleshow/47754083.cms (2015)

[14] Federalism and Fidelity – RTE Review (2014) – Oxfam India

[15] https://www.oxfamindia.org/sites/default/files/2019-02/Davos%20India%20Supplement.pdf – pg 4

[16] https://www.oxfamindia.org/sites/default/files/2019-02/Davos%20India%20Supplement.pdf – pg 4

[17] Federalism and Fidelity – RTE Review (2014) – Oxfam India

[18] https://www.oxfamindia.org/sites/default/files/2018-10/OIA-Community-Based-Monitoring-and-Grievance-Redressal-in-Schools-in-Delhi-1012-2015-en.pdf - Policy Brief - Community-Based Monitoring and Grievance Redressal in Schools in Delhi

[19] http://rteforumindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Year-9-Stocktaking-Report-RTE-Forum-draft.pdf

There are several schemes and programmes implemented by the Government of India to ensure child education in India. On 22 January 2015, Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched the Beti Bachao Beti Padhao campaign, to “change mindsets regarding the girl child”. The campaign was launch with an aim to raise awareness about the declining sex-ratio in India and the importance of girl child education.

Other government schemes for girl child education provide financial support to parents to educate their daughters. Some of these schemes are Sukanya Samriddhi Yojana (SSY), Balika Samriddhi Yojana (BSY), and Mukhyamantri Rajshri Yojana (MRY). These schemes provide benefits such as higher interest rates, direct financial support, and tax benefits to parents for investing in education of their girl child.

Even though some reports have shown increasing enrollment of the girl child, there are still several hurdles in girl child education in India. The World Bank’s Living Standards Measurement Study in Uttar Pradesh has shown increased girl child education in private schools over the years. The first data collection was done in 1997-98. The same set of households were surveyed in 2007-08 and then again in 2010-11. Enrolment rate of girls was only 50% as per the first survey. This showed significant improvement, with 65% enrolment in 2007-08 and 72% by 2010-11. [20]

Problem in Girl Child Education [21]

Financial constraints.

Financial restrictions create hurdles for many parents in educating the girl child. Usually, she is forced to stay at home to carry out household chores and take care of her younger siblings while the son in the family is sent to school. Even if some parents wish to educate their girl child, lack of quality schools or other social factors create restrictions.

Household Responsibilities

Many girls are forced to drop out of school because of household responsibilities. Losing a parent or a sick family members forces young girls to take up household chores. Social norms dictate that it is a woman’s duty to do domestic work or take care of sick family members. 12-year-old Meena from Uttar Pradesh, was pulled out of school to take care of household chores and her young siblings.

Early and Forced Marriages

Our society’s obsession with marriage has ruined many lives. Girls are denied education and instead forced to marry at an early age, often before she has attains the physical and emotional maturity to even understand what marriage is. Due to lack of education she cannot make an informed decision of whether she indeed wishes to marry or not, and has no say in choosing the person she is forced to spend her entire life with. Additionally, the later a girl marries, the more the dowry her parents are forced to pay.

Preference of sons over daughters

Son preference further creates problems for a girl child. The deep-set social norm that sons will take care of the parents in their old age, while girls will have to get married and leave the parents house leads to a lot of preferential treatment to the sons and subsequently, discrimination against the girl child from a very young age. This then leads to parents not giving any importance to the education of the girl child.

Lack of functional toilets

Lack of basic facilities such as funtional toilets and hand washing areas force children to stay out of school. Girls are especially affected due to lack of functional toiliets once they reach menstruation age. They may be either be absent from school on a regular basis, or drop out of school altogether.

Long Distance to School

In rural areas, children have to walk, often alone, through forests, rivers, or deserted areas, and cover a long distance to school. Due to increased risk of violence against girls, parents prefer their daughters stay safe at home. Devyani was pulled out of school because she had to walk alone to school, but with Oxfam India’s support she was enrolled back in school.

[20] https://www.isid.ac.in/~soham9r/doc/pvt_paper.pdf - Intra-Household Gender Disparity in School Choice: Evidence from Private Schooling in India – Soham Sahoo, July 2015

[21] https://donate.oxfamindia.org/girl-child-education

[22] https://www.oxfamindia.org/sites/default/files/PN-OIN-ES-Education-07-CSA-Efforts-Effective-Implementation-RTE-EN.pdf

In this chapter we will learn the role civil society plays in the education sector, and how its actions impact the implementation of education policies around the world.

What is a civil society organisation

There is no one clear definition of a civil society organisation (CSO). It is defined in different ways by different organisations.

A paper by World Health Organisation states that in the absence of a common defination, civil society is usually understood as the social arena existing between the state and the individial or household. It states that the civil sociey lacks regulatory power of the state and the economic power of the market but it provides social power to the ordinary people.

What is the role of civil society

Recently, CSOs have become more prominent across the world. They are growing in number and influence around the world. CSOs play a vital role in the development sector, by asserting the rights of the marginalised communities. Civil society organisations holds the government accountable and ensure their compliance with human rights and international treating and conventions. Oxfam India is one such organisation which mobilizes people and builds movement against discrimination .

On the other hand, governments and institutions around the world have become more motivated in response to the increasing influence of CSOs, to establish a formal mechanism of working with the CSOs.

What is the role of civil society in the education section

Civil society organisations has played an active role in the education sector. CSOs have raised issues ranging from implementation to advocacy. Civil society has brought about significant changes to national education policies and system, through advocacy, across the world, ensuring that the right to education is granted to each person.

By holding the government accountable, civil society organisations ensures that each individual has equal access to essential services and they can raise their voice against violations of their rights.

What is the role of civil society in education in India

Civil society organisations in India have been playing a crucial role, since more than a decade. They are strengthening the education system in India by actively participating in advocacy, at the national, regional and internation levels in the education sector. There is an increasing collaboration between national, regional, and international CSO, through the Global Campaign for Education (GCE) and Education for All moverment.

NGOs like Oxfam India campaigns for quality and free public education for all, with a network of other civil society organisations, think tanks, policy makers, parents, and teachers.

Oxfam India is building a movement of people working to end discrimination and create a free and just society.

Oxfam India is building a movement of Indians coming together to fight discrimination. We stand for the rights of the marginalized such as Adivasis, Dalits, and Muslims, with a special focus on women and girls. We work with the public and policymakers to find lasting solutions to build an inclusive and just India where everyone can have equal access to rights, be safe, get quality education and healthcare, make their voices heard and thrive. We campaign and mobilize people to stand up and speak out, to demand decisions and policies from the government that help them fight inequality and discrimination in India. We save, protect and rebuild lives in times of crisis and humanitarian disasters.

Oxfam India changed the lives of over 1 million people across six poorest states* in India last year and campaigned to reach out to tens of millions more across the country.

We put the rights of the marginalized at the heart of everything we do, as this will lead to the lasting change we need. Together, we can create a discrimination free India where everyone can live with dignity and free from inequality and injustice.

Joins us as we fight discrimination today, to end it for good.

(* Assam, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Odisha and Uttar Pradesh)

Why we are here

Discrimination in India has been a social evil for ages. It has affected millions of lives in the past and continues to affect people basis their gender, caste, and economic background.

Everyone has the right to safety, education, health, shelter, food, and water, and people should not have to fight for these rights every day.

There are millions who are deprived of basic fundamental rights and Oxfam India champions their right to be heard.

With Oxfam India’s efforts, communities live safer lives; have access to health and education, clean water, food, sanitation, and other fundamental needs.

Oxfam India strives for an inclusive and just society.

How we make it happen

Oxfam India helps people fight discrimination on four fronts.

- Working with Marginalized communities: We work at the grassroots to generate awareness amongst the most marginalized communities such as Adivasis, Dalit and Muslims to stand up and speak out, to demand their rights and policies that help them fight discrimination and injustice. We work with the most vulnerable people with a special focus on women and girls.

- Public Campaign & Policy making: We work with the public and policy makers to find lasting solutions to build a just and discrimination free India where everyone can have an equal access to rights, be safe, get an education, quality healthcare, make their voices heard and thrive, irrespective of their caste, gender and economic background.

- Humanitarian Response: We save, protect and rebuild lives in times of crisis and humanitarian disasters.

Our commitment

We are committed to the people, both of who we work with and our supporters.

Oxfam India believes in the power of people coming together for justice and against discrimination.

In our 68-year history, we have seen that, when people join hands, raise their voice and demand action, change happens. We are committed to the power of people to fight discrimination and help marginalized communities pull themselves out of inequality and injustice. This is why our work and organization are based in the communities who are most affected in the six poorest states of India so that we can deliver change quickly and with impact.

Oxfam India uniquely combines the power of the public and the learnings from grassroots with the strength of supporters, partners, and allies to make a positive impact in the lives of millions of people.

From supporting women farmers in Bihar to demanding good quality education for children in Uttar Pradesh, from mobilizing public support in Delhi, Bangalore and Hyderabad to delivering life-saving aid in Assam and Manipur, we strive to ensure that the most marginalized people are heard.

And we won’t stop until everyone in India can live a life of dignity free from discrimination.

Our vision for the future

Our vision is a just and discrimination free India. Oxfam India will always be there in times of crisis and injustice to fight the inequalities and discrimination affecting the lives of millions of Indians.

Over the next five years, we will help many more people of socially excluded groups (Dalit, Adivasis and Muslims), and especially women in ‘Oxfam India focus states’ exercise their rights of citizenship and live a life of dignity, free from discrimination.

And we cannot do it without your support. We need more voices to join us in speaking truth to power so that we can influence the policies and attitudes that will fight discrimination across the nation.

As India’s leading movement against discrimination, we will not rest until everyone in our country can live in a fairer, equal society, and leave injustice and discrimination behind forever.

In this chapter, we will explore how Oxfam India support girl child education in India and the impact we have created in the last year.

Oxfam India’s role in education

Oxfam India is working to achieve the goal of quality and affordable education for each child in India. We campaign for the right to education of people from the most marginalised communities, especially the girl child.

Gudiya had to discontinue her education after her parents migrated to Delhi from Assam. After Oxfam India’s intervention she was brought at par with regular students and is now on her way to be admitted in a government school in New Delhi.

We advocate for the proper implementation of the Right to Education Act. Oxfam India is the founding member of the National RTE Forum. The forum has almost 10,000 non-government organisations members. The National RTE Forum has been one of the biggest achievements of Oxfam India, in the education sector. The forum brings together like minded groups and people working towards the common goal of inclusive education in India. The forum ensures that different groups work together and learn and support each other. [23]

Activities undertaken by Oxfam India [24]

Social mobilisation .

Oxfam India works with grass root organisations and initiates debates and dialogues, with teachers, intellectuals, educationist, and the general public on various issues related to the state of education in India. Oxfam India engages with youth on ‘Inequality in Education’ .

We sensitise people from various sections of the society on the right to education, status of RTE, and advocate for the right of the education for children up to 18 years of age. We deploy media channels, form support groups inside the Parliament and among policy makers at both the centre and state level.

Campaign for Policy Changes

We campaign for stricter regulation of private schools and ensure that 25% reservation for children from economically weaker sections and marginalised groups is implemented. We campaign against all forms of privatization of education in India to ensure that education is a treated as a fundamental right and not a privilege. Oxfam India holds consulations on Right to Education with other civil society organisation in its focus states.

Effective implementation

Oxfam India works with the School Management Committees (SMCs) and local authorities, to ensure effective implementation of the RTE Act. We also work with community members to raise awareness about the issues of marginalised groups, especially the problems of girl child education to ensure fulfilment of the RTE Act’s goal.

Accountability

Oxfam India strives to ensure the government is held accountable for the gaps in the implementation of the RTE, through careful study of the policy and its implementation. We also suggest recommendations for better implementation of the Act.

Oxfam India’s impact

Impact in bihar.

Oxfam India along with its partners, Dalit Vikas Abhiyan Samiti (DVAS) is working towards ending caste based discrimination in schools in Bihar and creating awareness about the value of education among marginalised communities. The Musahar community in Samastipur district of Bihar, is especially discriminated against. Their children are put in separate classrooms and the teachers hardly teach them. Teachers and upper caste students hold the bias that they are “dirty” and “pollute the environment of the school”. Oxfam India and DVAS work towards changing these attitudes. After a series of meetings in 2018 Oxfam India and DVAS managed to push the school administration to let children from the community eat their mid-day meals with other students. The Musahar families consider this an important milestone and say it’s a “big change” they have seen in years. [25]

Impact in Delhi

When a study by Pratham revealed in 2013 that only 10% of the SMC parent members interviewed were aware that they were part of the SMC, Oxfam India and its partner JOSH (Joint Operation for Social Help) filed a complaint at the Central Information Commission (CIC)in 2011 evoking the Section 4 of the Right to Information Act (RTI), 2005. Section 4 of the RTI Act is a proactive disclosure section mandating all public authorities to share information with citizens about their functioning. Since the school is a public authority, compliance to Section 4 was demanded. [26] Read More about Oxfam India's work on Education in Delhi.

Impact in Jharkhand

Students were irregular in schools in Kolpotka village, Jharkhand. One of the reasons behind this was that they were taught in Hindi. Coming from the Munda tribe, speaking a different language, they could not grasp what was being taught. To raise interest of the students, Oxfam India and its partner Society for Participatory Action and Reflection (SPAR) introduced Multi Lingual Education (MLE) in the schools and appointed part-time teachers in April 2015, who took training in the tribal language. This helped students enrol back in school who had dropped out. The SMC too played a crucial role in getting children back to school. [27] Read More about Oxfam India's work on Education in Jharkhand.

Part-time teacher appointed by SPAR taking a class at Kolpotka village in West Singhbhum's Manoharpur block.

Impact in odisha.

Odisha has a high percentage of out-of-school children between six and fourteen years of age. One of the key reasons for high dropout rates is the language barrier in the Adivasi belts of the state. Most children in the Adivasi dominated areas have inadequate exposure to Odia, the main medium of teaching. In order to ensure access to quality, universal and inclusive elementary education, Oxfam India along with Sikshasandhan, an NGO based in Odisha, initiated Project Birsa in 2011. As part of the project, Sikshasandhan appointed teachers who could teach in the tribal languages. Eventually, school attendance increased in the Birsa focused schools. [28] Read More about Oxfam India's work on Education in Odisha.

Books in Odia and Ho made available, by Oxfam India and Sikshasandhan, to students of the 11 primary schools in Noto Gram Panchayat in Mayurbhanj district, Odisha.

Impact in uttar pradesh.