Essay on Oligopoly: Top 8 Essays on Oligopoly | Markets | Microeconomics

Here is a compilation of essays on ‘Oligopoly’ for class 9, 10, 11 and 12. Find paragraphs, long and short essays on ‘Oligopoly’ especially written for school and college students.

Essay on Oligopoly

Essay Contents:

- Essay on Payoff (Profit) Matrix

Essay # 1. Introduction to Oligopoly:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Two extreme market forms are monopoly (characterised by the existence of a single seller) and perfect competition (characterised by a large number of sellers). Competition is of two types- perfect competition and monopolistic competition. In perfect competition, all sellers sell homogeneous products while in monopolistic competition they sell heterogeneous products. In monopoly there is no rival.

So the monopolist is not concerned with the effect of his actions on rivals. In both types of competition, the number of firms is so large that the actions of any one seller have little, if any, effect on its competitors. An industry with only a few sellers is known as an oligopoly, a firm in such an industry is known as an oligopolist.

Although car-wash is a million rupee business, it is not exactly a product familiar to most consumers. However, often many familiar goods and services are supplied only by a few competing sellers, which means the industries we are talking about are oligopolies. An oligopoly is not necessarily made up of large firms. When a village has only two medicine shops, service there is just as much an oligopoly as air shuttle service between Mumbai and Pune.

Essentially, oligopoly is the result of the same factors that sometimes produce monopoly, but in somewhat weaker form. Honestly, the most important source of oligopoly is the existence of economies of scale, which give better producers a cost advantage over smaller ones. When these economies of scale are very strong, they lead to monopoly, but when they are not that strong they lead to competition among a small number of firms.

Since an oligopoly contains a small number of firms, any change in the firms’ price or output influences the sales and profits of competitors. Each firm must, therefore, recognise that changes in its own policies are likely to elicit changes in the policies of its competitors as well.

As a result of this interdependence, oligopolists face a situation in which the optimal decision of one firm depends on what other firms decide to do. And so there is opportunity for both conflict and cooperation. Oligopoly refers to a market situation in which the number of sellers is few, but greater than one. A special case of oligopoly is monopoly in which there are only two sellers.

Essay # 2. Characteristics of Oligopoly:

The notable characteristics of oligopoly are:

1. Price-Searching Behaviour :

An oligopolist is neither a price-taker (like a competitor) nor a price-maker (like a monopolist). It is a price-searcher. An oligopolist is neither a big enough part of the market to be able to act as a monopolist, nor a small enough part of the market to be able to act as a competitor. But each firm is a dominant part of the market.

In such a situation, competition among buyers will force all the sellers to charge a uniform price for a product. But each firm is sufficiently so large a part of the market that its actions will have noticeable effects upon his rivals. This means that if a single firm changes its output, the prices charged by all the firms will be raised or lowered.

2. Product Characteristics :

In oligopoly, there may be product differentiation as in monopolistic competition (called differentiated oligopoly) or a homogeneous product may be traded by all the few dominant firms (as in pure oligopoly).

3. Interdependence and Uncertainty :

In oligopoly no firm can take decision on price independently. It is because the decision to fix a new price or change an existing price will create reactions among the rival firms. But rivals’ reactions cannot be predicted accurately. If a firm reduces its price its rivals may reduce their prices or they may not. So there is lack of symmetry in the behaviour of rival firms.

This type of reaction of rivals is not found in perfect competition or monopolistic competition where all firms change their price in the same direction and by the same magnitude in order to remain competitive and survive in the long run. So the outcome of a firm’s decision is uncertain.

For this reason it is difficult to predict the total demand for the product of an oligopolistic industry. It is still more difficult, and in some situations virtually impossible, to estimate the share of an individual firm in industry’s output.

It is true that the consequences of attempted price variations on the part of an individual seller are uncertain. His rivals may follow his change, or they may not, but they will, in all likelihood, notice it. The results of any action on the part of an oligopolist or even a duopolist depend upon the reactions of his rivals. In short, it is not possible to define general price- quantity relations for an individual firm, since reaction patterns of rivals are highly uncertain and almost completely unknown.

4. Different Reaction Patterns and Use of Models :

It is not true to say that, in oligopoly, profit is always maximised. It is because an oligopolist does not have control over all the variables which affect his profit. Moreover, a variety of possible reaction patterns is possible in this market—there is a conjectural variation in this market.

Just as firm A’s profit depends on the output of firm B also, firm B’s profit, in its turn, depends on firm A’s output. This is why various models are used to describe the diverse behaviour of oligopoly markets where a variety of outcomes is possible.

5. Non-Price Competition :

As in monopolistic competition there is not only price competition but non-price competition as well in oligopoly (and, to some extent, in duopoly). For example, advertising is often a life and death question in this type of market due to strategic behaviour of all firms. In most oligopoly situations we find intermediate outcomes. Economists are yet to emerge with a definite behaviour pattern in oligopoly.

Essay # 3. Scope of Study of Oligopoly :

Here we study a few of the many possible reaction patterns in duopoly and oligopoly situations. The focus is on pure oligopoly. Here we assume that all firms produce a homogeneous product. We do not discuss the case of differentiated oligopoly and the issue of selling cost (advertising) separately. Of course, we discuss briefly Baumol’s sales maximisation hypothesis—without and with advertising.

The focus here is on the interdependence of the various sellers’ reactions, which is the essential distinguishing feature of oligopoly. If the influence of one seller’s quantity decision from the profit of another, δπ i /δq j , is negligible, the industry must be either perfectly competitive or monopolistically competitive. If δπ i /δq j , is perceptible, the industry is duopolistic or oligopolistic.

The optimum quantity and maximum profit of a duopolist or oligopolist depend upon the actions of the firms belonging to the industry. He can control only his own output level (or price, if his product is differentiated), but he has no direct control over other variables which are likely to (or do) affect his profits. In truth, the profit of each oligopolist is the result of the interaction of the decisions of all players in the market.

Since there are no generally accepted behavioural assumptions for oligopolists and duopolists as is found in other market forms, there are diverse patterns of behaviour and many different solutions for oligopolistic and duopolistic markets. Each solution is based on different types of models and each model is based on a different behavioural assumption or a set of assumptions.

Here we start with one or two simple duopoly models. The same analysis (solution) can be extended to cover any oligopolistic market. The earliest model of duopoly behaviour is the Cournot model, with which we may start our review of different oligopoly models. We end with the game theoretic treatment of oligopoly which shows decision-making under conflict.

Essay # 4. Models of Oligopoly:

1. the cournot model :.

The Cournot model (presented in 1838) is based on the analysis of a market in which two firms produce a homogeneous product. Augustin Cournot (a French economist) noticed that only two firms were producing mineral water for sale. He argued that each firm would choose quantity that would maximise profit, taking the quantity marketed by its competitor as given.

Two main features of the model are:

(i) Each firm chooses a quantity of output instead of price; and

(ii) In choosing its output each firm takes its rival’s output as given.

In Cournot’s model, then, strategies are quantities of output. Here we assume that firms produce a homogeneous good and know the market demand curve.

Each firm must decide how much to produce, and the two firms make their decisions at the same time. When taking its production decision, each duopolist takes into consideration its competitor. It knows that its competitor is also deciding how much to produce, and the market price will depend on the total output of both firms.

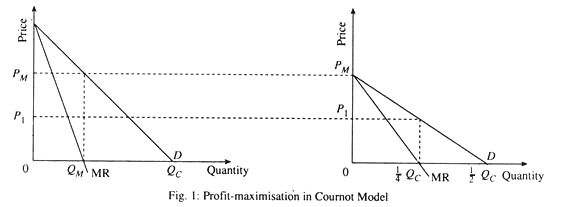

The essence of the Cournot model is that each firm treats the output level of its competitor as fixed and then decides how much to produce. Each Cournot’s duopolist believes that the other’s quantity will not change. In Fig. 1 when I produces Q M , II maximises its profit by producing 1/4Q C . In order to sell Q M plus Q c , the price must fall to P 1 . Here Q M is the monopoly output which is half the competitive output Q c .

The inverse demand function, stating price as a function of the aggregate quantity sold, is expressed as:

P =f (q 1 ) + q 2 … (1)

where q 1 and q 2 are the output levels of the duopolists. The total revenue of each duopolist depends upon his own output level as also as that of his rival:

R 1 = q 1 f 1 (q 1 + q 2 ) = R 1 (q 1 , q 2 )

R 2 = q 2 f 2 (q 1 + q 2 ) = R 2 (q 1 , q 2 ) … (2)

The profit of each equals his total (sales) revenue, less his cost, which depends upon his output level above:

π 1 = R 1 (q 1 , q 2 ) – C 1 (q 1 )

π 2 = R 2 (q 1 , q 2 ) – C 2 (q 2 ) … (3)

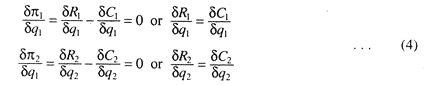

The basic behavioural assumption of the Cournot model is that each duopolist maximises his profit on the assumption that the quantity produced by his rival is invariant with respect to his own decision regarding output quantity. Duopolist I maximises π 1 with reference to q 1 , treating q 2 as a parameter, and duopolist II maximises π 2 , with reference to q 2 , treating q 1 as a parameter. Setting the partial derivatives of (3) equal to zero, we get:

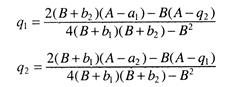

The solution of (7) is

Here OM is the marginal cost of producing the commodity. The second firm’s price is p 2 . The first firm’s profit function is composed of three segments. When p 1 < p 2 , the first firm captures the entire market, and its profit increases as its price increases. When p 1 > p 2 , the two firms split the total profits equal to distance CA, and each makes a profit equal to CB. When p 1 >p 2 , the first firm’s profit is zero because it sells nothing when its price exceeds the second firm’s price.

Criticisms:

The Bertrand model has been criticised on two main grounds. First, when firms produce a homogeneous good, it is more natural to compete by setting quantities rather than prices. Second, even if firms do set prices and choose the same price (as the model predicts), what share of total sales will go to each one? The model assumes that sales would be divided equally among the firms, but there is no reason why this must be the case.

However, despite these shortcomings, the Bertrand model is useful because it shows how the equilibrium outcome in an oligopoly can depend crucially on the firms’ choice of strategic variable.

3. The Stackelberg Model :

The Stackelberg model (presented by the German economist Heinrich von Stackelberg) is a modified version of the Cournot model. In the Cournot model, we assume that two duopolists make their output decisions at the same time. The Stackelberg model examines what happens if one of the firms can set its output first. The Stackelberg model of duopoly is different from the Cournot model, in which neither firm has any opportunity to react.

The model is based on the assumption that the profit of each duopolist is a function of the output levels of both:

π 1 = g 1 (q 1 , q 2 ) π 2 = g 2 (q 1 , q 2 ) … (1)

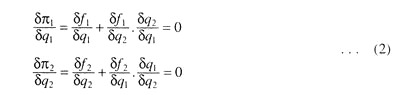

The Cournot solution is found out by maximising π 1 with reference to q 1 , assuming q 2 to be constant and π 2 with reference to q 2 , assuming q 1 to be constant. In general, each firm might make some other assumption about the response (reaction) of its only rival. In such a situation, profit-maximisation by the two duopolists requires the fulfillment of the following two conditions:

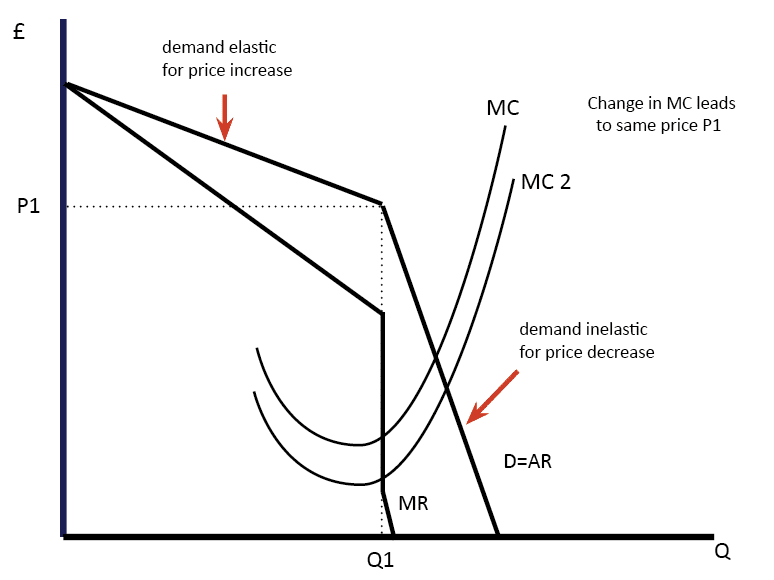

Since the firm’s demand curve is kinked, its combined marginal revenue curve is discontinuous. This means that the firm’s cost can change without leading to price change. In this figure, marginal cost could increase but would still equal marginal revenue at the original output level. This means that price remains the same.

The kinked demand curve model fails to explain oligopoly pricing. It says nothing about how marginal revenue firms arrived at the original price P̅ to start with. In fact, some arbitrary price is taken as both the starting and end point of our journey. Why firms did not arrive at some other price remains an open question. It just describes price rigidity but cannot explain it. In addition, the model has not been supported by empirical tests. In reality, rival firms do match price increases as well as price cuts.

Market-sharing Price Leadership :

Oligopolists often collude—jointly restrict supply to raise price and cooperate. This strategy can lead to higher profits. Collusion is, however, illegal. Moreover, one of the main impediments to implicitly collusive pricing is the fact that it is difficult for firms to agree (without talking to each other) on what the price should be.

Coordination becomes particularly problematic when cost and demand conditions—and, thus, the ‘correct’ price—are changing. However, benefits of cooperation can be enjoyed without actually colluding. One way of doing this is through price leadership. Price leadership may be provided by a low-cost firm or a dominant firm.

In this context, we may draw a distinction between price signalling and price leadership. Price signalling is a form of implicit collusion that sometimes gets around this problem. For example, a firm might announce that it has raised its price with the expectation that its competitors will take this announcement as a signal that they should also raise prices. If competitors follow, all of the firms (at least, in the short run) will earn higher profits.

At times, a pattern is established whereby one firm regularly announces price changes and other firms in the industry follow. This type of strategic behaviour is called price leadership— one firm is implicitly recognised as the ‘leader’. The other firms, the ‘price followers’, match its prices. This behaviour solves the problem of coordinating price: Everyone simply charges what the leader is charging.

Price leadership helps to overcome oligopolistic firms’ reluctance to change prices—for fear of being undercut. With changes in cost and demand conditions, firms may find it increasingly necessary to change prices that have remained rigid for some time. In that case, they wait for the leader to signal when and by how much price should change.

Sometimes a large firm will naturally act as a leader; sometimes different firms will act as a leader from time to time. In this context, we may discuss the dominant Firm model of leadership. This is known as market- sharing price leadership.

6. The Dominant Firm Model :

In some oligopolistic markets, one large firm has a major share of total sales while a group of smaller firms meet the residual demand by supplying the remainder of the market. The large firm might then act as a dominant firm, setting a price that maximises its own profits.

The other firms, which individually could exert little, if any, influence over price, would then act as perfect competitors; they all take the price set by the dominant firm as given and produce accordingly. But what price should the dominant firm set? To maximise profit, it must take into account how the output of the other firms depends on the price it sets.

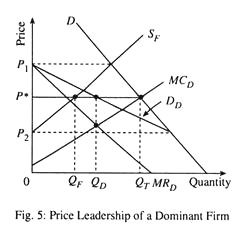

Fig. 5 shows how a dominant firm sets its prices. A dominant firm is one with a large share of total sales that sets price to maximise profits, taking into account the supply response of smaller firms. Here D is the market demand curve and S F is the supply curve (i.e., the aggregate marginal cost curves of the smaller firms, called competitive fringe firms). The dominant firm must determine its demand curve D D .

This curve is just the difference between market demand and the supply of fringe firms. For example, at price P 1 , the supply of fringe firms is just equal to market demand. This means that the dominant firm can sell nothing at this price. At a price P 2 or less, fringe firms will not supply any of the good, in which case, the dominant firm faces the market demand curve. If price lies between P 1 and P 2 , the dominant firm faces the demand curve D D .

The marginal cost curve of the dominant firm corresponding to D D is MR D . The dominant firm’s marginal cost curve is MC D . In order to maximise its profit, the dominant firm produces quantity Q D at the interaction of MR D and MC D . From the demand curve D D , we find P 0 . At this price, fringe firms sell a quantity Q F , thus the total quantity sold is Q T = Q D + Q F .

7. Collusive Oligopoly: The Cartel Model :

Various models have been formulated to explain the strategic behaviour of firms in an oligopolistic market. A price (cut-throat) competition exists among the rivals who try to oust the others from the market. Sometimes there exists a dominant firm that acts as the leader in the market while the others just follow the leader.

As a result, there happens to be a clear possibility of the formation of a cartel by the rival firms in an oligopolistic market in order to eliminate competition among themselves. This is termed as “collusive oligopoly” because the firms somehow manage to combine together in order to behave collectively as a single monopoly.

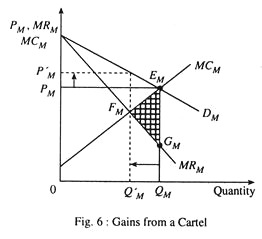

Now let us see graphically what incentives the firms get for forming a cartel. In Fig. 6, the market demand curve is given by the D M the total supply curve is the horizontal summation of the marginal cost curves of all existing firms in the industry, which is denoted by MC M .

The market equilibrium is attained at the point of intersection between the D M (demand curve) and the marginal cost curve MC M , if the firms compete with each other. OP M is the equilibrium price at which the total output of the industry is OQ M .

In order to determine its own quantity, each firm equates this price to its marginal cost. The sum of the quantities of the firms is OQ. If the firms form a cartel in order to act as a monopolist, the price rises to OP ‘ M and the quantity is reduced to OQ ‘ M to be in equilibrium. Now, when the quantity is being reduced by Q M Q’ M , then all the firms together save the cost represented by the area below the MC M curve which is Q M E M F M Q ‘ M .

Thus, a rise in price due to a reduction in the quantity is followed by a decrease in the total revenue represented by the area below the MR M curve, i.e., area Q M G M F M Q’ M . This, in turn, shows that the cost saved exceeds the loss in revenue and, so, all the firms taken as a whole can increase their profit represented by the area E M F M G M . The prospect of earning this extra profit actually acts as the incentive to form a cartel in the oligopoly market structure.

Since the cartel is formed, all firms agree together to produce the total quantity OQ’ M . In order to carry this out, each and every firm is allotted a quota or a certain portion of production such that the sum of all quotas is equal to OQ M . For this, the best way of quota allotment would be to treat each firm as a separate entity (plant) under the same monopolist. Thus, all the firms have the same marginal cost (MC) such that MC = MR (marginal revenue).

Finally, the total profit is maximised because the total output is produced at the minimum cost.

Each and every firm can increase its profit by reducing the profits of other firms, simply by increasing its output quantity above the allotted quota. The system of cartel formation must guard against the desire of individual firms to violate the quota and the cartel breaks down when the cost of guarding against quota violation is very high.

The OPEC is an example of collusive oligopoly or cartel in which members (producers) explicitly agree to cooperate in setting prices and output levels. All the producers in an industry need not and often do not join the cartel. But if most producers adhere to the cartel’s agreements, and if market demand is sufficiently inelastic, the cartel may drive prices well above competitive levels.

Two conditions for success:

Two conditions must be fulfilled for cartel success. First, a stable cartel organisation must be formed whose members agree on price and production levels and both adhere to that agreement. The second condition is the potential for monopoly power. A cartel cannot raise price much if it faces a highly elastic demand curve. If the potential gains from cooperation are large, cartel members will have more incentive to share their organisational problems.

Analysis of Cartel Pricing:

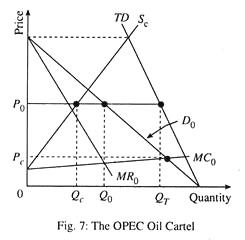

Cartel pricing can be analysed by using the dominant firm model of oligopoly. It is because a cartel usually accounts for only a portion of total production and must take into account the supply response of competitive (non-cartel) producers when it sets price. Here we illustrate the OPEC oil cartel.

Fig. 7 illustrates the case of OPEC. Total demand TD is the world demand curve for crude oil, and S c is the competitive (non-OPEC) supply curve. The demand for OPEC oil D 0 is the difference between total demand (TD) and competitive supply (SC), and MR 0 is the corresponding marginal revenue curve.

MC 0 is OPEC’s marginal cost curve; OPEC has much lower production costs than do non-OPEC producers. OPEC’s marginal revenue and marginal cost are equal at quantity Q 0 , which is the quantity that OPEC will produce. Here we see from OPEC s demand curve that the price will be P 0 .

Since both total demand and non-OPEC supply are inelastic, the demand for OPEC oil is also fairly inelastic; thus the cartel has substantial monopoly. In the 1970s, it used that power to drive prices well above competitive levels.

In this context, it is important to distinguish between short-run and long-run supply and demand curves. The total demand and non-OPEC supply curves in Fig. 7 apply to short-or intermediate-run analysis. In the long run, both demand and supply will be much more elastic, which means that OPEC’s demand curve will also be much more elastic.

We would thus expect that, in the long run, OPEC would be unable to maintain a price that is so much above the competitors’ level. In truth, during 1982-99, oil prices fell steadily, mainly because of the long- run adjustment of demand and non-OPEC supply.

However, cartel is not an unmixed blessing. No doubt cartel members can talk to one another in order to formalize an agreement. But it is not that easy to reach a consensus. Different members may have different costs, different assessments of market demand, and even different objectives, and they may, therefore, want to set prices at different levels.

Furthermore, each member of the cartel will be tempted to “cheat” by lowering its price slightly to capture a larger market share than it was allotted. Most often, only the threat of a long-term return to competitive prices deters cheating of this sort. But if the profits from cartelization are large enough, that threat may be sufficient.

Essay # 5. Sales (Revenue) Maximisation :

W.J. Baumol presented an alternative hypothesis to profit maximisation, viz., sales (revenue) maximisation. He has suggested that large oligopolistic firms do not maximise profit, but rather maximise sales revenue, subject to the constraint that profit equals or exceeds some minimum accepted level. Various empirical studies support Baumol’s hypothesis. And it accurately captures some aspects of oligopolistic firms’ behaviour.

Most important, when firms are uncertain about their demand curve they actually face, or, when they cannot accurately estimate the marginal costs of their output (due to uncertainty about factor prices, or when they produce more than one product), the decision to try to maximise sales appears to be consistent with their long-term survival. This is why many oligopolist firms seek to maximise their market share in order to protect themselves from the adverse effects of uncertain market environment.

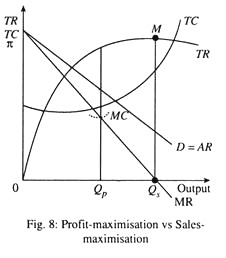

Graphical Analysis :

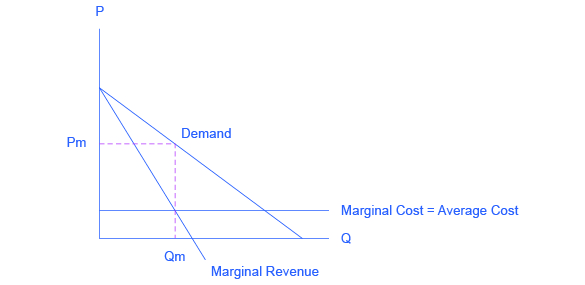

A revenue-maximising oligopolist would choose to produce that level of output for which MR = 0. When MR = 0, TR is maximum. That is, the oligopolist should proceed to the point at which selling any extra unit(s) actually leads to a fall in TR. This choice is illustrated in Fig. 8.

For the firm which faces the demand curve D, TR is maximum when output is q s . For q < q s , MR is positive. This means that selling more units increases TR (though not necessarily profit). For q > q s , however, MR is negative. So further sales actually reduce TR because of price cuts that are necessary to induce consumers to buy more. We know that

MR = P(1 – 1/e p ) … (1)

MR = 0 if e p = 1, in which case TR will be maximum. TR is constant in a small neighbourhood of that output quantity at M 1 P = 0, TR is maximum, and when TR is maximum, e p = 1.

We may now compare the revenue-maximisation choice with the profit-maximising level of output, q s . At q p , MR equals marginal cost MC in Fig. 8. Increasing output beyond q p would reduce profits since MR < MC. Even though TR continues to increase up to q s , units of output beyond q p bring in less than they cost to produce. Since marginal revenue is positive at q p , equation (1) shows that demand must be elastic (e p > 1) at this point.

Essay # 6. Constrained Revenue Maximisation :

A firm that chooses to maximise TR is neither taking into account its costs nor the profitability of the output that it is selling. And it is quite possible that the output level q s in Fig. 8 yields negative profit to the firm. However, it is not possible to any firm to survive for ever with negative profits. So it may be more realistic to assume that firms do meet some minimum level (target rate) of profit from their activities.

Thus, even though oligopolists may be prompted to produce more than q p with a view to maximising revenue, they may produce less than q p units in order to ensure an acceptable level of profit. They will, therefore, behave as constrained revenue maximises and will choose to produce an output level which lies between q p and q s .

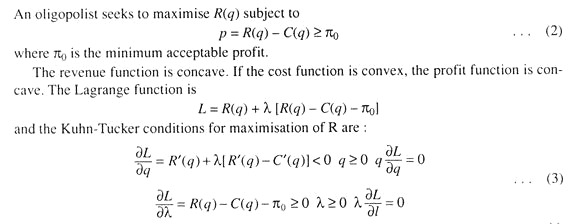

Mathematical Analysis :

How firms in Oligopoly compete

Oligopoly is a market structure in which a few firms dominate the industry; it is an industry with a five firm concentration ratio of greater than 50%.

In Oligopoly, firms are interdependent; this means their decisions (price and output) depend upon how the other firms behave:

- Barriers to entry are likely to be a feature of Oligopoly

- There are different models to explain how firms may behave

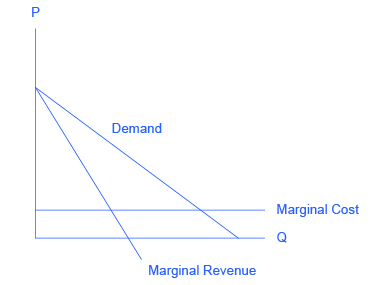

The kinked demand curve model suggests firms will be profit maximisers.

Kinked Demand Curve Diagram

At p1 if firms increased their price, consumers would buy from the other firms. Therefore, they would lose a large share of the market and demand will be elastic. Therefore, firms will lose revenue by increasing the price.

If firms cut price then they would gain a big increase in market share. However, it is unlikely that firms will allow this. Therefore, other firms follow suit and cut-price as well. Therefore demand will only increase by a small amount: Demand is inelastic for a price cut and revenue would fall.

This model suggests price will be rigid because there is no incentive for firms to change the price

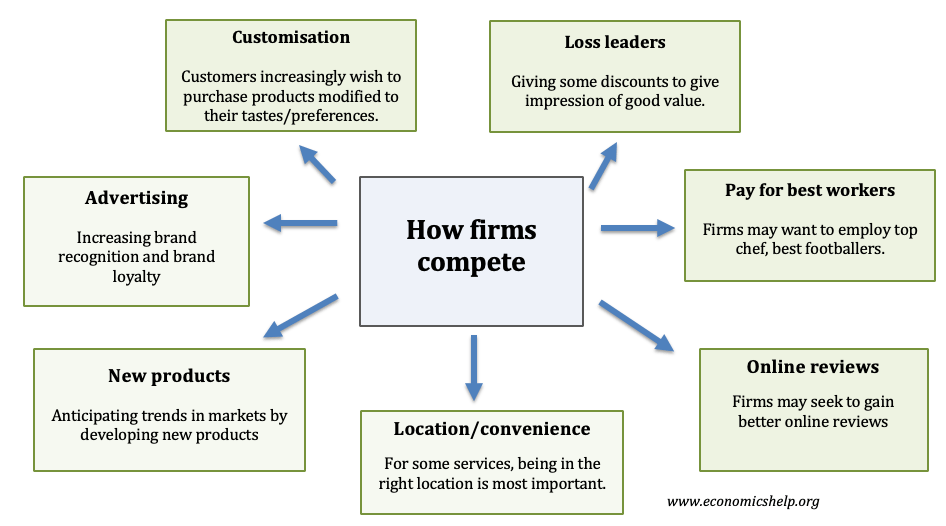

If prices are rigid and firms have little incentive to change prices they will concentrate on non-price competition . This occurs when firms seek to increase revenue and sales by various methods other than price.

For example, a firm could spend money on advertising to raise the profile of their product and try and increase brand loyalty, if successful this will increase market sales. Advertising is a big feature of many oligopolies such as soft drinks and cars. Alternatively, they could introduce loyalty cards or improve the quality of their after sales service. When buying a plane ticket price is not the only factor consumers look at, they may prefer airlines with more leg room, air miles e.t.c.

Non-price competition depends upon the nature of the product. For example, advertising is very important for soft drinks but less important for petrol.

However, in reality, this model doesn’t always occur. Often the objectives of firms are not to maximise profit. For example, they may wish to increase the size of their firm and maximise sales. If this is the case, they may be willing to take part in a price war, even if this does lead to lower profits. Price wars involve firms selling goods at very low prices to try and gain market share. For example, newspapers such as the Times and the Sun have recently been sold very cheaply. Price wars are more likely if:

- 1. Large firms are able to cross subsidise one market from profits elsewhere

- 2. In a recession, markets are more competitive as firms seek to retain customers

However, price wars may only be short-term

A firm may engage in predatory pricing ; this occurs when the incumbent firm seeks to force a new firm out of business by selling at a very low price so that it cannot remain profitable.

Using game theory

Game theory looks at different possible outcomes of oligopoly – depending on how firms react to different decisions.

If the firms in oligopoly seek to increase market share the most likely outcome is that they both set low prices and make a low profit (£3m each) However if the firms could come to some agreement either formal or tacit collusion – they could both agree to raise prices. This will require the firms to reduce output and stick to the more limited supply. If they set high prices, then they will both be able to make monopoly profits (£8m each)

However, when prices are high, there is a temptation to undercut your rival and benefit from both high market prices and high output. This enables higher profit – £10m, but if firms start to cheat – then rivals are likely to retaliate by cutting prices too.

Collusion is possible in oligopoly, but it depends on several factors. Collusion is more likely if

1. There are a small number of firms, who are well known to each other – this makes it easier to stick to output quotas 2. A dominant firm, who is able to have a lot of influence in setting the price. 3. Barriers to entry, this is important to stop other firms entering to take advantage of the high profits 4. Effective communication and monitoring of output and costs 5. Similar production costs and therefore will want to raise prices at the same rate 6. Effective punishment strategies for firms who cheat 7. No effective government legislation, e.g. collusion is illegal in the UK.

Conclusion:

There is no certainty in how firms will compete in Oligopoly; it depends upon the objectives of the firms, the contestability of the market and the nature of the product. Some oligopolies compete on price; others compete on the quality of the product.

Examples of Competition in oligopoly

Petrol is a homogenous product and so is likely to be quite stable in prices. Firms often move petrol prices in response to changes in the oil price. However, the introduction of the supermarket own brand petrol has changed the market. Tesco and Sainsbury’s are more willing to sell cheaper petrol to attract customers to shop at their supermarket.

Coffee market

This takeaway coffee at 99p is quite cheap – suggesting a competitive oligopoly. However, for many customers, the price of coffee is secondary to the quality and environment of the coffee shop. Traditional coffee shops like Costa and Starbucks use more non-price competition to attract customers – as much as offering cheap prices.

In fact, there is a danger selling cheap coffee – may indicate to consumers lower quality.

How firms compete in general

See more – How firms compete

- Pricing strategies

Oligopoly Notes & Questions (A-Level, IB)

Relevant Exam Boards: A-Level (Edexcel, OCR, AQA, Eduqas, WJEC), IB, IAL, CIE Edexcel Economics Notes Directory | AQA Economics Notes Directory | IB Economics Notes Directory

Oligopoly Definition: An Oligopoly is a market structure where only a few sellers dominate the market.

Oligopoly Examples & Explanation: Because there are only a few firms (players) in an Oligopoly, they tend to be highly interdependent of one another – meaning they will take in account each others’ actions when trying to compete in the market. Another characteristic is these markets also exhibit high barriers to entry, such that new firms cannot easily enter into the market. This characteristic is shared with Monopolies (one firm dominating) and Duopolies (two-firms dominating), explaining how they can dominate the market with large amounts of market share. If we consider the oil & gas industry, they tend to be an Oligopoly in most countries (think Shell, BP, Exxon) due to the huge capital investment required for oil exploration/mining, making it difficult for new producers to enter into the market. When a large oil/gas producer sells their oil at a lower price to increase their sales volume, other producers are likely to lower their prices as well to protect their share of the market. As a result, Oligopolies tend to keep market prices stable and focus on non-price competition, so that firms can avoid a price war. However, the negative oil prices from the coronavirus pandemic is also caused by other factors, including a lack of storage capacity for oil producers forcing them to sell, and a global lack of demand for oil during the crisis. In general, oil producers in OPEC agree on an amount of output to maintain a relatively high price for oil, meaning higher profits for the industry.

Oligopoly Economics Notes with Diagrams

Oligopoly video explanation – econplusdal.

The left video explains oligopoly and the kinked-demand curve, the right looks at competition and cartels in the oligopoly market structure.

Oligopoly Multiple Choice Questions (A-Level)

Oligopoly essay questions (ib), receive news on our free economics classes, notes/questions updates, and more, oligopoly in the news, related a-level, ib economics resources.

Follow us on Facebook , TES and SlideShare for resource updates.

You may also like

Types of Business Objectives Notes & Questions (A-Level, IB Economics)

Relevant Exam Boards: A-Level (Edexcel, OCR, AQA, Eduqas, WJEC), IB, IAL, CIE Edexcel Economics Notes Directory | AQA Economics Notes Directory | […]

Fiscal Policy Notes & Questions (A-Level, IB)

Financial Markets Notes (A-Level, IB)

Related Exam Boards: GCE A-Level, IB (HL), Edexcel (A2), OCR, AQA, Eduqas, WJEC Looking for revision notes, past exam questions and teaching […]

Phillips Curve Notes & Questions (A-Level, IB Economics)

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Learning Objectives

- Explain why and how oligopolies exist

- Contrast collusion and competition

- Interpret and analyze the prisoner’s dilemma diagram

- Evaluate the tradeoffs of imperfect competition

Many purchases that individuals make at the retail level are produced in markets that are neither perfectly competitive, monopolies, nor monopolistically competitive. Rather, they are oligopolies. Oligopoly arises when a small number of large firms have all or most of the sales in an industry. Examples of oligopoly abound and include the auto industry, cable television, and commercial air travel. Oligopolistic firms are like cats in a bag. They can either scratch each other to pieces or cuddle up and get comfortable with one another. If oligopolists compete hard, they may end up acting very much like perfect competitors, driving down costs and leading to zero profits for all. If oligopolists collude with each other, they may effectively act like a monopoly and succeed in pushing up prices and earning consistently high levels of profit. Oligopolies are typically characterized by mutual interdependence where various decisions such as output, price, advertising, and so on, depend on the decisions of the other firm(s). Analyzing the choices of oligopolistic firms about pricing and quantity produced involves considering the pros and cons of competition versus collusion at a given point in time.

Why Do Oligopolies Exist?

A combination of the barriers to entry that create monopolies and the product differentiation that characterizes monopolistic competition can create the setting for an oligopoly. For example, when a government grants a patent for an invention to one firm, it may create a monopoly. When the government grants patents to, for example, three different pharmaceutical companies that each has its own drug for reducing high blood pressure, those three firms may become an oligopoly.

Similarly, a natural monopoly will arise when the quantity demanded in a market is only large enough for a single firm to operate at the minimum of the long-run average cost curve. In such a setting, the market has room for only one firm, because no smaller firm can operate at a low enough average cost to compete, and no larger firm could sell what it produced given the quantity demanded in the market.

Quantity demanded in the market may also be two or three times the quantity needed to produce at the minimum of the average cost curve—which means that the market would have room for only two or three oligopoly firms (and they need not produce differentiated products). Again, smaller firms would have higher average costs and be unable to compete, while additional large firms would produce such a high quantity that they would not be able to sell it at a profitable price. This combination of economies of scale and market demand creates the barrier to entry, which led to the Boeing-Airbus oligopoly for large passenger aircraft.

The product differentiation at the heart of monopolistic competition can also play a role in creating oligopoly. For example, firms may need to reach a certain minimum size before they are able to spend enough on advertising and marketing to create a recognizable brand name. The problem in competing with, say, Coca-Cola or Pepsi is not that producing fizzy drinks is technologically difficult, but rather that creating a brand name and marketing effort to equal Coke or Pepsi is an enormous task.

Collusion or Competition?

When oligopoly firms in a certain market decide what quantity to produce and what price to charge, they face a temptation to act as if they were a monopoly. By acting together, oligopolistic firms can hold down industry output, charge a higher price, and divide up the profit among themselves. When firms act together in this way to reduce output and keep prices high, it is called collusion . A group of firms that have a formal agreement to collude to produce the monopoly output and sell at the monopoly price is called a cartel . See the following Clear It Up feature for a more in-depth analysis of the difference between the two.

Collusion versus cartels: How can I tell which is which?

In the United States, as well as many other countries, it is illegal for firms to collude since collusion is anti-competitive behavior, which is a violation of antitrust law. Both the Antitrust Division of the Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission have responsibilities for preventing collusion in the United States.

The problem of enforcement is finding hard evidence of collusion. Cartels are formal agreements to collude. Because cartel agreements provide evidence of collusion, they are rare in the United States. Instead, most collusion is tacit, where firms implicitly reach an understanding that competition is bad for profits.

The desire of businesses to avoid competing so that they can instead raise the prices that they charge and earn higher profits has been well understood by economists. Adam Smith wrote in Wealth of Nations in 1776: “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.”

Even when oligopolists recognize that they would benefit as a group by acting like a monopoly, each individual oligopoly faces a private temptation to produce just a slightly higher quantity and earn slightly higher profit—while still counting on the other oligopolists to hold down their production and keep prices high. If at least some oligopolists give in to this temptation and start producing more, then the market price will fall. Indeed, a small handful of oligopoly firms may end up competing so fiercely that they all end up earning zero economic profits—as if they were perfect competitors.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

Because of the complexity of oligopoly, which is the result of mutual interdependence among firms, there is no single, generally-accepted theory of how oligopolies behave, in the same way that we have theories for all the other market structures. Instead, economists use game theory , a branch of mathematics that analyzes situations in which players must make decisions and then receive payoffs based on what other players decide to do. Game theory has found widespread applications in the social sciences, as well as in business, law, and military strategy.

The prisoner’s dilemma is a scenario in which the gains from cooperation are larger than the rewards from pursuing self-interest. It applies well to oligopoly. The story behind the prisoner’s dilemma goes like this:

Two co-conspiratorial criminals are arrested. When they are taken to the police station, they refuse to say anything and are put in separate interrogation rooms. Eventually, a police officer enters the room where Prisoner A is being held and says: “You know what? Your partner in the other room is confessing. So your partner is going to get a light prison sentence of just one year, and because you’re remaining silent, the judge is going to stick you with eight years in prison. Why don’t you get smart? If you confess, too, we’ll cut your jail time down to five years, and your partner will get five years, also.” Over in the next room, another police officer is giving exactly the same speech to Prisoner B. What the police officers do not say is that if both prisoners remain silent, the evidence against them is not especially strong, and the prisoners will end up with only two years in jail each.

The game theory situation facing the two prisoners is shown in Table 1 . To understand the dilemma, first consider the choices from Prisoner A’s point of view. If A believes that B will confess, then A ought to confess, too, so as to not get stuck with the eight years in prison. But if A believes that B will not confess, then A will be tempted to act selfishly and confess, so as to serve only one year. The key point is that A has an incentive to confess regardless of what choice B makes! B faces the same set of choices, and thus will have an incentive to confess regardless of what choice A makes. Confess is considered the dominant strategy or the strategy an individual (or firm) will pursue regardless of the other individual’s (or firm’s) decision. The result is that if prisoners pursue their own self-interest, both are likely to confess, and end up doing a total of 10 years of jail time between them.

The game is called a dilemma because if the two prisoners had cooperated by both remaining silent, they would only have had to serve a total of four years of jail time between them. If the two prisoners can work out some way of cooperating so that neither one will confess, they will both be better off than if they each follow their own individual self-interest, which in this case leads straight into longer jail terms.

The Oligopoly Version of the Prisoner’s Dilemma

The members of an oligopoly can face a prisoner’s dilemma, also. If each of the oligopolists cooperates in holding down output, then high monopoly profits are possible. Each oligopolist, however, must worry that while it is holding down output, other firms are taking advantage of the high price by raising output and earning higher profits. Table 2 shows the prisoner’s dilemma for a two-firm oligopoly—known as a duopoly . If Firms A and B both agree to hold down output, they are acting together as a monopoly and will each earn $1,000 in profits. However, both firms’ dominant strategy is to increase output, in which case each will earn $400 in profits.

Can the two firms trust each other? Consider the situation of Firm A:

- If A thinks that B will cheat on their agreement and increase output, then A will increase output, too, because for A the profit of $400 when both firms increase output (the bottom right-hand choice in Table 2 ) is better than a profit of only $200 if A keeps output low and B raises output (the upper right-hand choice in the table).

- If A thinks that B will cooperate by holding down output, then A may seize the opportunity to earn higher profits by raising output. After all, if B is going to hold down output, then A can earn $1,500 in profits by expanding output (the bottom left-hand choice in the table) compared with only $1,000 by holding down output as well (the upper left-hand choice in the table).

Thus, firm A will reason that it makes sense to expand output if B holds down output and that it also makes sense to expand output if B raises output. Again, B faces a parallel set of decisions.

The result of this prisoner’s dilemma is often that even though A and B could make the highest combined profits by cooperating in producing a lower level of output and acting like a monopolist, the two firms may well end up in a situation where they each increase output and earn only $400 each in profits . The following Clear It Up feature discusses one cartel scandal in particular.

What is the Lysine cartel?

Lysine, a $600 million-a-year industry, is an amino acid used by farmers as a feed additive to ensure the proper growth of swine and poultry. The primary U.S. producer of lysine is Archer Daniels Midland (ADM), but several other large European and Japanese firms are also in this market. For a time in the first half of the 1990s, the world’s major lysine producers met together in hotel conference rooms and decided exactly how much each firm would sell and what it would charge. The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), however, had learned of the cartel and placed wire taps on a number of their phone calls and meetings.

From FBI surveillance tapes, following is a comment that Terry Wilson, president of the corn processing division at ADM, made to the other lysine producers at a 1994 meeting in Mona, Hawaii:

I wanna go back and I wanna say something very simple. If we’re going to trust each other, okay, and if I’m assured that I’m gonna get 67,000 tons by the year’s end, we’re gonna sell it at the prices we agreed to . . . The only thing we need to talk about there because we are gonna get manipulated by these [expletive] buyers—they can be smarter than us if we let them be smarter. . . . They [the customers] are not your friend. They are not my friend. And we gotta have ‘em, but they are not my friends. You are my friend. I wanna be closer to you than I am to any customer. Cause you can make us … money. … And all I wanna tell you again is let’s—let’s put the prices on the board. Let’s all agree that’s what we’re gonna do and then walk out of here and do it.

The price of lysine doubled while the cartel was in effect. Confronted by the FBI tapes, Archer Daniels Midland pled guilty in 1996 and paid a fine of $100 million. A number of top executives, both at ADM and other firms, later paid fines of up to $350,000 and were sentenced to 24–30 months in prison.

In another one of the FBI recordings, the president of Archer Daniels Midland told an executive from another competing firm that ADM had a slogan that, in his words, had “penetrated the whole company.” The company president stated the slogan this way: “Our competitors are our friends. Our customers are the enemy.” That slogan could stand as the motto of cartels everywhere.

How to Enforce Cooperation

How can parties who find themselves in a prisoner’s dilemma situation avoid the undesired outcome and cooperate with each other? The way out of a prisoner’s dilemma is to find a way to penalize those who do not cooperate.

Perhaps the easiest approach for colluding oligopolists, as you might imagine, would be to sign a contract with each other that they will hold output low and keep prices high. If a group of U.S. companies signed such a contract, however, it would be illegal. Certain international organizations, like the nations that are members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) , have signed international agreements to act like a monopoly, hold down output, and keep prices high so that all of the countries can make high profits from oil exports. Such agreements, however, because they fall in a gray area of international law, are not legally enforceable. If Nigeria, for example, decides to start cutting prices and selling more oil, Saudi Arabia cannot sue Nigeria in court and force it to stop.

Visit the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries website and learn more about its history and how it defines itself.

Because oligopolists cannot sign a legally enforceable contract to act like a monopoly, the firms may instead keep close tabs on what other firms are producing and charging. Alternatively, oligopolists may choose to act in a way that generates pressure on each firm to stick to its agreed quantity of output.

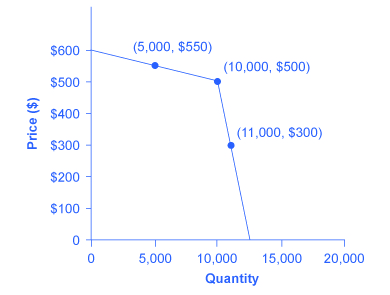

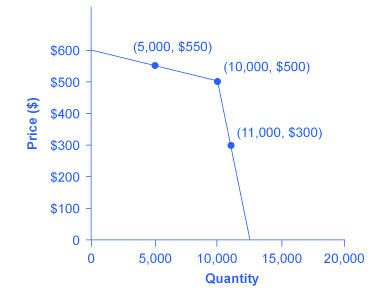

One example of the pressure these firms can exert on one another is the kinked demand curve , in which competing oligopoly firms commit to match price cuts, but not price increases. This situation is shown in Figure 1 . Say that an oligopoly airline has agreed with the rest of a cartel to provide a quantity of 10,000 seats on the New York to Los Angeles route, at a price of $500. This choice defines the kink in the firm’s perceived demand curve. The reason that the firm faces a kink in its demand curve is because of how the other oligopolists react to changes in the firm’s price. If the oligopoly decides to produce more and cut its price, the other members of the cartel will immediately match any price cuts—and therefore, a lower price brings very little increase in quantity sold.

If one firm cuts its price to $300, it will be able to sell only 11,000 seats. However, if the airline seeks to raise prices, the other oligopolists will not raise their prices, and so the firm that raised prices will lose a considerable share of sales. For example, if the firm raises its price to $550, its sales drop to 5,000 seats sold. Thus, if oligopolists always match price cuts by other firms in the cartel, but do not match price increases, then none of the oligopolists will have a strong incentive to change prices, since the potential gains are minimal. This strategy can work like a silent form of cooperation, in which the cartel successfully manages to hold down output, increase price , and share a monopoly level of profits even without any legally enforceable agreement.

Figure 1. A Kinked Demand Curve. Consider a member firm in an oligopoly cartel that is supposed to produce a quantity of 10,000 and sell at a price of $500. The other members of the cartel can encourage this firm to honor its commitments by acting so that the firm faces a kinked demand curve. If the oligopolist attempts to expand output and reduce price slightly, other firms also cut prices immediately—so if the firm expands output to 11,000, the price per unit falls dramatically, to $300. On the other side, if the oligopoly attempts to raise its price, other firms will not do so, so if the firm raises its price to $550, its sales decline sharply to 5,000. Thus, the members of a cartel can discipline each other to stick to the pre-agreed levels of quantity and price through a strategy of matching all price cuts but not matching any price increases.

Many real-world oligopolies, prodded by economic changes, legal and political pressures, and the egos of their top executives, go through episodes of cooperation and competition. If oligopolies could sustain cooperation with each other on output and pricing, they could earn profits as if they were a single monopoly. However, each firm in an oligopoly has an incentive to produce more and grab a bigger share of the overall market; when firms start behaving in this way, the market outcome in terms of prices and quantity can be similar to that of a highly competitive market.

Tradeoffs of Imperfect Competition

Monopolistic competition is probably the single most common market structure in the U.S. economy. It provides powerful incentives for innovation, as firms seek to earn profits in the short run, while entry assures that firms do not earn economic profits in the long run. However, monopolistically competitive firms do not produce at the lowest point on their average cost curves. In addition, the endless search to impress consumers through product differentiation may lead to excessive social expenses on advertising and marketing.

Oligopoly is probably the second most common market structure. When oligopolies result from patented innovations or from taking advantage of economies of scale to produce at low average cost, they may provide considerable benefit to consumers. Oligopolies are often buffeted by significant barriers to entry, which enable the oligopolists to earn sustained profits over long periods of time. Oligopolists also do not typically produce at the minimum of their average cost curves. When they lack vibrant competition, they may lack incentives to provide innovative products and high-quality service.

The task of public policy with regard to competition is to sort through these multiple realities, attempting to encourage behavior that is beneficial to the broader society and to discourage behavior that only adds to the profits of a few large companies, with no corresponding benefit to consumers. Monopoly and Antitrust Policy discusses the delicate judgments that go into this task.

The Temptation to Defy the Law

Oligopolistic firms have been called “cats in a bag,” as this chapter mentioned. The French detergent makers chose to “cozy up” with each other. The result? An uneasy and tenuous relationship. When the Wall Street Journal reported on the matter, it wrote: “According to a statement a Henkel manager made to the [French anti-trust] commission, the detergent makers wanted ‘to limit the intensity of the competition between them and clean up the market.’ Nevertheless, by the early 1990s, a price war had broken out among them.” During the soap executives’ meetings, which sometimes lasted more than four hours, complex pricing structures were established. “One [soap] executive recalled ‘chaotic’ meetings as each side tried to work out how the other had bent the rules.” Like many cartels, the soap cartel disintegrated due to the very strong temptation for each member to maximize its own individual profits.

How did this soap opera end? After an investigation, French antitrust authorities fined Colgate-Palmolive, Henkel, and Proctor & Gamble a total of €361 million ($484 million). A similar fate befell the icemakers. Bagged ice is a commodity, a perfect substitute, generally sold in 7- or 22-pound bags. No one cares what label is on the bag. By agreeing to carve up the ice market, control broad geographic swaths of territory, and set prices, the icemakers moved from perfect competition to a monopoly model. After the agreements, each firm was the sole supplier of bagged ice to a region; there were profits in both the long run and the short run. According to the courts: “These companies illegally conspired to manipulate the marketplace.” Fines totaled about $600,000—a steep fine considering a bag of ice sells for under $3 in most parts of the United States.

Even though it is illegal in many parts of the world for firms to set prices and carve up a market, the temptation to earn higher profits makes it extremely tempting to defy the law.

An oligopoly is a situation where a few firms sell most or all of the goods in a market. Oligopolists earn their highest profits if they can band together as a cartel and act like a monopolist by reducing output and raising price. Since each member of the oligopoly can benefit individually from expanding output, such collusion often breaks down—especially since explicit collusion is illegal.

The prisoner’s dilemma is an example of game theory. It shows how, in certain situations, all sides can benefit from cooperative behavior rather than self-interested behavior. However, the challenge for the parties is to find ways to encourage cooperative behavior.

The United States Department of Justice. “Antitrust Division.” Accessed October 17, 2013. http://www.justice.gov/atr/.

eMarketer.com. 2014. “Total US Ad Spending to See Largest Increase Since 2004: Mobile advertising leads growth; will surpass radio, magazines and newspapers this year. Accessed March 12, 2015. http://www.emarketer.com/Article/Total-US-Ad-Spending-See-Largest-Increase-Since-2004/1010982.

Federal Trade Commission. “About the Federal Trade Commission.” Accessed October 17, 2013. http://www.ftc.gov/ftc/about.shtm.

when a few large firms have all or most of the sales in an industry

economic conditions in the industry, for example, economies of scale or control of a critical resource, that limit effective competition

the total number of units of a good or service consumers are willing to purchase at a given price

when firms act together to reduce output and keep prices high

a group of firms that collude to produce the monopoly output and sell at the monopoly price

a branch of mathematics often used by economists that analyzes situations in which players must make decisions and then receive payoffs based on what decisions the other players make

a game in which the gains from cooperation are larger than the rewards from pursuing self-interest

an oligopoly with only two firms

a perceived demand curve that arises when competing oligopoly firms commit to match price cuts, but not price increases

Oligopoly Copyright © 2020 by Rice University; Dean, Elardo, Green, Wilson, Berger. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10 Oligopoly

10.1 theory of the oligopoly, why do oligopolies exist.

Many purchases that individuals make at the retail level are produced in markets that are neither perfectly competitive, monopolies, nor monopolistically competitive. Rather, they are oligopolies. Oligopoly arises when a small number of large firms have all or most of the sales in an industry. Examples of oligopoly abound and include the auto industry, cable television, and commercial air travel. Oligopolistic firms are like cats in a bag. They can either scratch each other to pieces or cuddle up and get comfortable with one another. If oligopolists compete hard, they may end up acting very much like perfect competitors, driving down costs and leading to zero profits for all. If oligopolists collude with each other, they may effectively act like a monopoly and succeed in pushing up prices and earning consistently high levels of profit. We typically characterize oligopolies by mutual interdependence where various decisions such as output, price, and advertising depend on other firm(s)’ decisions. Analyzing the choices of oligopolistic firms about pricing and quantity produced involves considering the pros and cons of competition versus collusion at a given point in time.

A combination of the barriers to entry that create monopolies and the product differentiation that characterizes monopolistic competition can create the setting for an oligopoly. For example, when a government grants a patent for an invention to one firm, it may create a monopoly. When the government grants patents to, for example, three different pharmaceutical companies that each has its own drug for reducing high blood pressure, those three firms may become an oligopoly.

Similarly, a natural monopoly will arise when the quantity demanded in a market is only large enough for a single firm to operate at the minimum of the long-run average cost curve. In such a setting, the market has room for only one firm, because no smaller firm can operate at a low enough average cost to compete, and no larger firm could sell what it produced given the quantity demanded in the market.

Quantity demanded in the market may also be two or three times the quantity needed to produce at the minimum of the average cost curve—which means that the market would have room for only two or three oligopoly firms (and they need not produce differentiated products). Again, smaller firms would have higher average costs and be unable to compete, while additional large firms would produce such a high quantity that they would not be able to sell it at a profitable price. This combination of economies of scale and market demand creates the barrier to entry, which led to the Boeing-Airbus oligopoly (also called a duopoly) for large passenger aircraft.

The product differentiation at the heart of monopolistic competition can also play a role in creating oligopoly. For example, firms may need to reach a certain minimum size before they are able to spend enough on advertising and marketing to create a recognizable brand name. The problem in competing with, say, Coca-Cola or Pepsi is not that producing fizzy drinks is technologically difficult, but rather that creating a brand name and marketing effort to equal Coke or Pepsi is an enormous task.

The existence of oligopolies can lead to the combination of many firms into larger firms. This is discussed next.

Types of Firm Integration

Conglomerate.

From: Wikipedia: Conglomerate (company)

A conglomerate is a combination of multiple business entities operating in entirely different industries under one corporate group , usually involving a parent company and many subsidiaries . Often, a conglomerate is a multi-industry company . Conglomerates are often large and multinational .

Horizontal Integration

From: Wikipedia: Horizontal integration

Horizontal integration is the process of a company increasing production of goods or services at the same part of the supply chain . A company may do this via internal expansion, acquisition or merger . [1] [2] [3]

The process can lead to monopoly if a company captures the vast majority of the market for that product or service. [3]

Horizontal integration contrasts with vertical integration , where companies integrate multiple stages of production of a small number of production units.

Benefits of horizontal integration to both the firm and society may include economies of scale and economies of scope . For the firm, horizontal integration may provide a strengthened presence in the reference market. It may also allow the horizontally integrated firm to engage in monopoly pricing , which is disadvantageous to society as a whole and which may cause regulators to ban or constrain horizontal integration. [5]

An example of horizontal integration in the food industry was the Heinz and Kraft Foods merger. On March 25, 2015, Heinz and Kraft merged into one company, the deal valued at $46 Billion. [8] [9] Both produce processed food for the consumer market.

On November 16, 2015, Marriott International announced that it would purchase Starwood Hotels for $13.6 billion, creating the world’s largest hotel chain once the deal closed. [11] The merger was finalized on September 23, 2016. [12]

AB-Inbev acquisition of SAB Miller for $107 Billion which completed in 2016, is one of the biggest deals of all time. [13]

Vertical Integration

From: Wikipedia: Vertical integration

In microeconomics and management , vertical integration is an arrangement in which the supply chain of a company is owned by that company. Usually each member of the supply chain produces a different product or (market-specific) service, and the products combine to satisfy a common need. It is contrasted with horizontal integration , wherein a company produces several items which are related to one another. Vertical integration has also described management styles that bring large portions of the supply chain not only under a common ownership, but also into one corporation (as in the 1920s when the Ford River Rouge Complex began making much of its own steel rather than buying it from suppliers).

Vertical integration and expansion is desired because it secures the supplies needed by the firm to produce its product and the market needed to sell the product. Vertical integration and expansion can become undesirable when its actions become anti-competitive and impede free competition in an open marketplace. Vertical integration is one method of avoiding the hold-up problem . A monopoly produced through vertical integration is called a vertical monopoly .

Vertical integration is often closely associated to vertical expansion which, in economics , is the growth of a business enterprise through the acquisition of companies that produce the intermediate goods needed by the business or help market and distribute its product. Such expansion is desired because it secures the supplies needed by the firm to produce its product and the market needed to sell the product. Such expansion can become undesirable when its actions become anti-competitive and impede free competition in an open marketplace.

The result is a more efficient business with lower costs and more profits. On the undesirable side, when vertical expansion leads toward monopolistic control of a product or service then regulative action may be required to rectify anti-competitive behavior. Related to vertical expansion is lateral expansion , which is the growth of a business enterprise through the acquisition of similar firms, in the hope of achieving economies of scale .

Vertical expansion is also known as a vertical acquisition. Vertical expansion or acquisitions can also be used to increase scales and to gain market power. The acquisition of DirecTV by News Corporation is an example of forward vertical expansion or acquisition. DirecTV is a satellite TV company through which News Corporation can distribute more of its media content: news, movies and television shows. The acquisition of NBC by Comcast is an example of backward vertical integration. For example, in the United States, protecting the public from communications monopolies that can be built in this way is one of the missions of the Federal Communications Commission .

One of the earliest, largest and most famous examples of vertical integration was the Carnegie Steel company. The company controlled not only the mills where the steel was made, but also the mines where the iron ore was extracted, the coal mines that supplied the coal , the ships that transported the iron ore and the railroads that transported the coal to the factory, the coke ovens where the coal was cooked, etc. The company focused heavily on developing talent internally from the bottom up, rather than importing it from other companies. Later, Carnegie established an institute of higher learning to teach the steel processes to the next generation.

Oil companies , both multinational (such as ExxonMobil , Royal Dutch Shell , ConocoPhillips or BP ) and national (e.g., Petronas ) often adopt a vertically integrated structure, meaning that they are active along the entire supply chain from locating deposits , drilling and extracting crude oil , transporting it around the world, refining it into petroleum products such as petrol/gasoline , to distributing the fuel to company-owned retail stations, for sale to consumers.

Lateral Integration

Lateral expansion , in economics , is the growth of a business enterprise through the acquisition of similar companies, in the hope of achieving economies of scale or economies of scope . Unchecked lateral expansion can lead to powerful conglomerates or monopolies .

Lateral integration differs from horizontal integration as the integration is not exact. For example, one of the examples of horizontal integration was one hotel chain buying another. This did not enhance the company’s product offerings other than having more hotel options.

On the other hand, Parker Hannifin acquired Lord Corporation. While the two companies make similar types of products, their product offerings were distinct. There was not much overlap with the types of products offered. Instead, Parker Hannifin was not able to provide a far greater product offering in the given sectors.

The Strength of an Oligopoly

From: Wikipedia: Concentration ratio

The most common concentration ratios are the CR 4 and the CR 8 , which means the market share of the four and the eight largest firms. Concentration ratios are usually used to show the extent of market control of the largest firms in the industry and to illustrate the degree to which an industry is oligopolistic . [1]

N-firm concentration ratio is a common measure of market structure and shows the combined market share of the N largest firms in the market. For example, the 5-firm concentration ratio in the UK pesticide industry is 0.75, which indicates that the combined market share of the five largest pesticide sellers in the UK is about 75%. N-firm concentration ratio does not reflect changes in the size of the largest firms.

Concentration ratios range from 0 to 100 percent. The levels reach from no, low or medium to high to “total” concentration

Perfect competition

If there are N firms in an industry and we are looking at the top n of them, equal market share for all of them means that CR n = n/N . All other possible values will be greater than this.

No concentration

If CR n is close to 0%, (which is only possible for quite a large number of firms in the industry N ) this means perfect competition or at the very least monopolistic competition . If for example CR 4 =0 %, the four largest firm in the industry would not have any significant market share.

Low concentration

0% to 40%. [5] This category ranges from perfect competition to an oligopoly.

Medium concentration

40% to 70%. [5] An industry in this range is likely an oligopoly.

High concentration

70% to 100%. [5] This category ranges from an oligopoly to monopoly.

Total concentration

100% means an extremely concentrated oligopoly . If for example CR 1 = 100%, there is a monopoly .

10.2 Game theory

Game theory basics, dominant versus non-dominant strategies.

From: Wikipedia: Cooperative game theory

In game theory , a cooperative game (or coalitional game ) is a game with competition between groups of players (“coalitions”) due to the possibility of external enforcement of cooperative behavior (e.g. through contract law ). Those are opposed to non-cooperative games in which there is either no possibility to forge alliances or all agreements need to be self-enforcing (e.g. through credible threats ). [1]

Cooperative games are often analysed through the framework of cooperative game theory, which focuses on predicting which coalitions will form, the joint actions that groups take and the resulting collective payoffs. It is opposed to the traditional non-cooperative game theory which focuses on predicting individual players’ actions and payoffs and analyzing Nash equilibria . [2] [3]

Cooperative game theory provides a high-level approach as it only describes the structure, strategies and payoffs of coalitions, whereas non-cooperative game theory also looks at how bargaining procedures will affect the distribution of payoffs within each coalition. As non-cooperative game theory is more general, cooperative games can be analyzed through the approach of non-cooperative game theory (the converse does not hold) provided that sufficient assumptions are made to encompass all the possible strategies available to players due to the possibility of external enforcement of cooperation. While it would thus be possible to have all games expressed under a non-cooperative framework, in many instances insufficient information is available to accurately model the formal procedures available to the players during the strategic bargaining process, or the resulting model would be of too high complexity to offer a practical tool in the real world. In such cases, cooperative game theory provides a simplified approach that allows the analysis of the game at large without having to make any assumption about bargaining powers.

Types of Strategies

General strategy.

This is simply any rule that a player uses. These strategies can be “good” or “bad.” For example, if you have to choose heads or tails for a coinflip, you may use the strategy “tails never fails” and always pick tails even though there is no advantage to this strategy. Additionally, when playing the game of Blackjack, you may have a rule that you always hit when you have a score of 20. If you do not know how to play Blackjack, I will simply state that this is generally a very, very bad idea! Even though it is a poor strategy, it is still a strategy nonetheless.

Dominant Strategy

From: Wikipedia: Strategic dominance

In game theory , strategic dominance (commonly called simply dominance ) occurs when one strategy is better than another strategy for one player, no matter how that player’s opponents may play. Many simple games can be solved using dominance.

Nash Equilibrium

From: Wikipedia: Nash equilibrium

In terms of game theory, if each player has chosen a strategy, and no player can benefit by changing strategies while the other players keep theirs unchanged, then the current set of strategy choices and their corresponding payoffs constitutes a Nash equilibrium.

Stated simply, Alice and Bob are in Nash equilibrium if Alice is making the best decision she can, taking into account Bob’s decision while his decision remains unchanged, and Bob is making the best decision he can, taking into account Alice’s decision while her decision remains unchanged. Likewise, a group of players are in Nash equilibrium if each one is making the best decision possible, taking into account the decisions of the others in the game as long as the other parties’ decisions remain unchanged.

Informally, a strategy profile is a Nash equilibrium if no player can do better by unilaterally changing his or her strategy. To see what this means, imagine that each player is told the strategies of the others. Suppose then that each player asks themselves: “Knowing the strategies of the other players, and treating the strategies of the other players as set in stone, can I benefit by changing my strategy?”

If any player could answer “Yes”, then that set of strategies is not a Nash equilibrium. But if every player prefers not to switch (or is indifferent between switching and not) then the strategy profile is a Nash equilibrium. Thus, each strategy in a Nash equilibrium is a best response to all other strategies in that equilibrium. [13]

The Nash equilibrium may sometimes appear non-rational in a third-person perspective. This is because a Nash equilibrium is not necessarily Pareto optimal . [Note: We do not talk about Pareto optimality in this class, but you can think of it as a best-case for everyone situation.]

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

From: Wikipedia: Prisoner’s dilemma

The prisoner’s dilemma is a standard example of a game analyzed in game theory that shows why two completely rational individuals might not cooperate, even if it appears that it is in their best interests to do so. It was originally framed by Merrill Flood and Melvin Dresher while working at RAND in 1950. Albert W. Tucker formalized the game with prison sentence rewards and named it “prisoner’s dilemma”, [1] presenting it as follows:

Two members of a criminal gang are arrested and imprisoned. Each prisoner is in solitary confinement with no means of communicating with the other. The prosecutors lack sufficient evidence to convict the pair on the principal charge, but they have enough to convict both on a lesser charge. Simultaneously, the prosecutors offer each prisoner a bargain. Each prisoner is given the opportunity either to betray the other by testifying that the other committed the crime, or to cooperate with the other by remaining silent. The offer is: If A and B each betray the other, each of them serves two years in prison If A betrays B but B remains silent, A will be set free and B will serve three years in prison (and vice versa) If A and B both remain silent, both of them will serve only one year in prison (on the lesser charge).