- Culture & Lifestyle

- Madhesh Province

- Lumbini Province

- Bagmati Province

- National Security

- Koshi Province

- Gandaki Province

- Karnali Province

- Sudurpaschim Province

- International Sports

- Brunch with the Post

- Life & Style

- Entertainment

- Investigations

- Climate & Environment

- Science & Technology

- Visual Stories

- Crosswords & Sudoku

- Corrections

- Letters to the Editor

- Today's ePaper

Without Fear or Favour UNWIND IN STYLE

What's News :

- Beijing on anti-China activities in Nepal

- Overcharging school admission fees

- Dilapidated Rolpa district prison

- homosexual relationship

The problem with buses in Nepal

A popular proverb describes the local bus services in Bogota, Columbia: ‘la guerra del centavo’ which can roughly be translated into English as ‘the penny war’. It signifies the unhealthy competition between public transportation service providers that would kill hundreds of people every year in accidents caused by buses scrabbling to collect passengers. The cause of this war was old-fashioned, disorganised, unregulated and inefficient method of service in public transportation. Since the drivers of public buses made their living from the fare collected from the passenger, they used to fight with each other for every passenger in the road, resulting in unsafe driving and unreliable service. Returning home, to our capital city Kathmandu, we see a similar war occurring, seriously degrading our public transportation sector. But perhaps we can find a solution to ameliorate the chaotic traffic system. In this article, I will focus primarily on the root cause of unmanaged/chaotic transportation service in town, which resembles the penny war, and the effects of this chaos on the larger system.

Almost a year ago, after the government of Nepal announced the termination of the syndicate system of public transportation, one new private company entered this sector with big promises in one popular route and established itself on that route with the help of the administration and the public. The promises this company made were things like free wi-fi and television on-board; free services for the elderly and people with disabilities; exclusive seats for pregnant mothers, women, the aged; competitive fares; timely services; an efficient ticket system; and friendly behaviour from their staff. It has barely been a year, and almost all of the above-mentioned promises have been left unfulfilled. Even worse, the bus company has contracted out their buses to their ‘staff’ on a daily basis and the staff pay some amount to bus company and, in return, can run the buses as they like. The result is irregular and irresponsible bus service. Regular maintenance is rare, resulting in frequent stoppages and stranded passengers.

Other public transportation service providers are no better; all are engaged in this war. Oversupply during the day-time means that the streets are jam-packed with small, low capacity buses filled with exhausted passengers. At the same time, the sporadic presence of public vehicles during early hours and late nights means that many people are limited in their travel. The fare collection system, moreover, is informal; tickets are non-existent. The root cause of the penny war is this poor fare collection system with no record of how much tariff is collected by the conductor. The more fare they collect, the more the cut of the conductor and driver is. This then leads to unhealthy and risky competition. Extreme rivalry leads to dangerous driving, as they compete to reach the next stop as fast as possible to get passengers. Stops are congested as buses wait there until they are over capacity, or a competing vehicle arrives. This motivates drivers to disrespect time schedules, if there are any, and stop anywhere a prospective passenger may be. Drivers drive zigzag and stop as they wish on the road leading to disturbances for fellow drivers, which could cause long traffic jams or accidents.

Boarding and alighting off the bus is dangerous in such a scenario; sometimes passengers have to get in and out of moving vehicles. The safety of the passengers and other vehicles is compromised. In extreme cases, if the passenger numbers are low, the conductor orders all riders to get off the bus. In short, the penny war has caused unsafe driving, high accident rates, and the maltreatment of commuters, among other terrible consequences. Our streets have been the battlefield of public buses—and daily commuters are being crushed in that fight regularly.

An improvement in the quality of public buses is impossible as long as this penny war continues. The amelioration of this war depends upon the capability of institutions that oversee, manage and regulate this sector. The existing organisation, with the current intuitional and legal arrangements, is not capable of doing this huge task. There is also the need for a form of mass rapid transit system, which will provide efficient and reliable service through reduced travel times, wider networks, exclusive right-of-way infrastructure, efficient fare collection systems, and faster boarding and disembarking methods.

The mayor of Bogota, Enrique Penalosa ended their penny war with the introduction of transmilenio, an efficient and cost-effective new bus transport system which alleviated congestion and reduced air pollutionin the city. As its name suggest this was the system designed with the aim of satisfying the mobility need of the people of new millennium and it actually fulfilled its promise. According to the Centre for Public Impact, transmilenio users are saving an average of 223 hours annually; travel time is reduced by 32 percent; 9 percent of its commuters are new users who used to commute by cars; deaths, injuries and robberies on buses are reduced by 92 percent, 75 percent and 83 percent respectively; and air pollution has decreased by 40 percent. Transmilenio is a bus rapid transit (BRT) system where both the public and private sectors share responsibility for the delivery of public transportation. As transport researcher Alan Gilbert (2007) suggested, transmilenio was a ‘miracle cure’ for Bogota’s public transportation.

It is a pity that neither the new proposal being discussed at the Cabinet nor the new legislation just passed by Kathmandu Metropolitan City regarding transportation mention the BRT system. They are engaged in small scale changes such as the colour coding of buses, stopping only at stations etc. which were already in place but could not solve the problems in the sector. There is no doubt that introduction of a mass rapid transit system in some form is inevitable.

Smaller vehicles and organisations are being displaced by larger vehicles and institutions globally. There are many technological and institutional options available today regarding mass rapid transit. But, unfortunately, our concerned agencies and policy makers are completely out of the loop and are making policies without being informed about the appropriate technology and organisational setting for urban public transportation. They are so enamoured of dreams of metro and mono rail that they have failed to look at examples of other developing cities that have successfully implemented bus rapid transit systems-which are rail-like in efficiency but bus-like in cost.

Timalsina tweets at @lonelybidur

Read Other Opinions

Provincial bottlenecks

Decoding NEPSE’s surprise moves

Bollywood’s supporting role in India’s elections

On the right track

A liberal argument against identity politics

Climate change causes marine ‘coldwaves’ too

Editor's picks.

Kathmandu Valley’s toxic air exacerbates respiratory illness

Melodrama for monarchy

Flood survivors struggle to rebuild their lives 15 years on

Jobs being created in Nepal lack quality: Experts

Kathmandu’s public transport remains an ordeal for many

E-paper | april 21, 2024.

- Read ePaper Online

Public transport in Nepal: What are real problems? What’s the solution?

In the context of Nepal, public transportation remained the most basic means of mobilisation for the majority of the population. Road transportation plays a vital role in Nepal as it is rapidly increasing with the growing urbanisation.

As the National Action Plan for Electric Mobility reported, more than 90 per cent of the total domestic movement of goods and passengers in Nepal depends on public road transportation. However, various studies and my own personal experiences reflected that the existing quality and the system of road transportation have not been passenger-friendly. Yet, the latest scenario indicates that concerned authorities and stakeholders have not been aware of promoting the existing quality of road transportation.

As a result, public transport has become the most problematic and challenging means of transportation. On the other hand, such serious issues of transportation have not become the major agenda of politicians during and after the elections.

So, how can these issues be dealt with? Is not there any prospect?

Mismanagement in public transportation

I observed and experienced in both local and long-route journeys on public transport vehicles various problems related to mismanagement of the in-bus environment and disturbances in the journey from the outside, particularly created by the poor condition of the road .

I remember hearing loud music, crowded passengers even having no space for proper standing, ongoing debates with passengers while collecting fare , and often impolite language of bus staff just to name a few.

They reflect how the rights of passengers of having comfortable, luxurious, healthy, and secure journeys have been ignored and the regulatory mechanism of the government of Nepal has become less effective. As a result, it has become a profit-making mechanism rather than a service provider to the public.

It is obvious that there has not been a lack of rules for regulating the public transport sector. However, there has been a problem in the implementation of such rules. The most challenging aspect is that there have been syndicates and trade unions related to various political parties, which directly and indirectly are responsible to create such an unmanageable situation.

Exploitation of passengers

Moreover, a peer-reviewed research article claims that the syndicate/cartel system of Nepali public transport has become a great means for transporters to exploit passengers. This clearly suggests public transport in Nepal has not been secure and passenger-friendly.

In addition, the study by Prajapati et al.(2019) , conducted in the Kathmandu valley, reported that limited infrastructure of transport and rapid growth of private vehicles spoiled the quality of the pick-hour journey and further brought tremendous challenges related to transport such as pollution, congestion, and accidents to name a few.

That has ultimately become an obstacle to establishing a passenger-friendly public transport system. This further indicates that new strategies and strong regulatory mechanisms need to be maintained to modify the sector to address the rights and maintain a passenger-friendly environment.

The solution

Keeping a passenger-friendly environment in public transportation not only encourages the passengers to use their time for creative activities but also contributes to their perception of the short duration of their journey time. For instance, a study by Watts and Urry (2008) says travel time can be minimised by filling various activities and enjoyments in the journey such as interaction with other passengers, utilising wireless networks, sight scenes etc, and it gets reflected in passengers’ psychological experiences.

Overall, the passengers should get an opportunity to utilise their time involving themselves in certain useful activities without being disturbed on their journey.

Although many attempts were made and a number of luxurious buses were added, the overall condition of the public transport system in Nepal has remained almost the same. Many roads were made and are under construction. However, the focus on transforming and making a healthy passenger-friendly environment has been ignored.

The road transportation system can be more fruitful for both the passengers and the transportation service providers if the quality of roads can be improved, implementing a strict regulatory system, modernising public transportation, and adding the latest facilities such as an online payment system (for those who can).

React to this post

Ghimire is an MPhil scholar at Nepal Open University.

Conversation

Login to comment, or use social media, forgot password, related news.

Silent struggles: Confronting the consequences of inaction on sexual harassment in public transport

Nepal’s struggle with unorganised and unstable public transportation crowds

Public transport fair goes down

Public transport fares come down in the Bagmati province including Kathmandu

Ministry forms task force to find solutions to current public transport issues

Govt hikes interprovince public transport fares. Here’s the complete list

Xiaomi 14 in Nepal: Is it the best in its category?

NEPSE fell though increase in share prices

Vivo V30 Lite 4G: Budget option with colour changing back launched in Nepal

Former PM Khanal and Secretary Shah designated election commanders

Engendering transitional justice: Obstacles and the way forward

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Subscribe to Onlinekhabar English to get notified of exclusive news stories.

Editor's Pick

Rape survivors in Nepal’s armed conflict demand justice and accountability

National sports policies limited to paper: 21 sports associations operating against the policy

Impacts of new rules implementation for landing in the Everest region

The trials and tribulations of CIB

A journey from Nepal to China

Nirmala Rai claims victory in 170 km Manjushree Trail despite no prior practice

Embarking on a sacred voyage: From Dang, Nepal to Ayodhya, India

Cryptocurrencies: A potential game-changer for Nepali migrant workers’ remittances

Price list: Best smartphones under Rs 1 lakh in Nepal as of April 2024

Understanding Pre-Eclampsia: A concerning condition for maternal health in Nepal

User registration form.

The Official Journal of the Pan-Pacific Association of Input-Output Studies (PAPAIOS)

- Open access

- Published: 08 December 2022

How strong is demand for public transport service in Nepal? A case study of Kathmandu using a choice-based conjoint experiment

- Tulsi Ram Aryal 1 ,

- Masaru Ichihashi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1707-7659 2 &

- Shinji Kaneko 2

Journal of Economic Structures volume 11 , Article number: 29 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

4413 Accesses

Metrics details

A public transport system is the most efficient and equitable solution to the challenges of urban mobility and climate change. To improve public transport, technological innovations, policy interventions, and behavioral changes should all be applied appropriately; however, there is a lack of information about the demand for public transport services in developing countries. This paper aims to measure the degree of demand for public transport services by comparing various factors used as a case study in Kathmandu, one of the most congested urban areas in a developing country. We designed a choice-based conjoint experiment with five attributes: mode of transport, waiting time, one-way fare per km, commute time per km, and payment method. Our results indicate that 73% of the respondents are in favor of changing the current transport policy and wish for a shift to public transport, which means that most commuters are in favor of the proposed mode of transport, that is, MRT. On the other hand, the study reveals that respondents have a negative evaluation of motorbikes, one of the most popular modes of transport in Kathmandu. Our results, showing users’ unsatisfactory situation with motorbikes as a transport measure, provide transport planners guidance for addressing current public transport policies, indicating a massive rapid transit system with a low fare would be highly welcome in a typical congestion area like Kathmandu.

1 Introduction

Kathmandu Valley belongs to Bagmati Province and extends into three administrative districts of Nepal, namely, Kathmandu, Bhaktapur, and Lalitpur, with a total area of 899 sq km (Fig. 1 ). The three districts have two metropolitan areas, the metropolitan city of Kathmandu and the metropolitan city of Lalitpur, and 16 municipalities. Kathmandu is the capital of the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal and is the country’s most important political, administrative, educational, cultural, and commercial center. In the 2011 census year, the total population of the Kathmandu Valley was 2,517,023, with an annual growth rate of 4.63%. This represents 9.32% of the country’s total population, in just 0.49% of the country’s area. The Central Bureau of Statistics of Nepal predicts that the population of the Kathmandu Valley will reach four million by 2035 (CBS 2018 ; JICA 2017 ).

Kathmandu valley and ring road covered area. (Source) Bhattarai et al ( 2019 )

The road transport system provides the main mode of mobility in Nepal. Rapid urbanization and increasing economic activities in cities have dramatically increased the demand for vehicles in urban areas. Due to ineffective public transport services, people are attracted to private vehicles, and the number of private vehicles is increasing rapidly compared to that of public vehicles. In the last 15 years, the number of motorbikes and low-occupancy modes of public transport, that is, minibusses and microbuses increased rapidly. Although the government has invested in the expansion of roads in the city of Kathmandu, the increasing number of private vehicles means that the traffic situation remains unchanged. This shows that expanding the road alone is not a sustainable solution for improving public transport. Considering the geographic area and the distance of the city from business and official areas, it is necessary to offer reliable public transport and nonmotorized transport even in cities such as Kathmandu. The Kathmandu Valley is completely dominated by motorbikes, which constitute 79.1% of the total fleet, followed by private vehicles (cars, vans, and jeeps) at 12.42%, heavy-duty vehicles at 4%, and public transport vehicles at 2.67%, and others, with an overall annual growth rate of 14% (DOTM 2019 ). The share of low-occupancy vehicles, that is, minibusses and microbuses, represents 94% of all public transport vehicles, and large buses make up only 6% (JICA 2017 ). For the past decade, the road transport service in the Kathmandu Valley has been affected by insufficient road length, narrow and busy roads, unattended traffic, poor traffic management infrastructure, a mix of old and new vehicles, and a multimodal public transport system. Kathmandu Valley faces an unprecedented level of traffic congestion, frequent vehicular accidents, and an increasingly unreliable public transit system (Bhattarai et al. 2019 ). The quality of service of the current public transport system in Kathmandu is poor, and public transport involves more travel time than private modes of travel. A mass rapid transit (MRT) system should be implemented to reduce congestion, decrease fossil energy consumption, and decrease air pollution (Dhakal 2006 ; JICA 2017 ; KSUTP 2014 , 2016 ; MoUD 2017 ; IBN 2017 , Bajracharya and Shrestha 2017 ; ICIMOD 2017 ). The current public transport system in the Kathmandu Valley is complex, and the quality of service is poor (World Bank 2019 ). Due to its bowel-shaped geography, gusty winds rarely remove vehicular emissions from the urban atmosphere, making Kathmandu one of Asia’s most polluted cities, the 100th city on the global pollution index (Bhattarai et al. 2019 ).

Transport is the most important social and environmental issue in the world (Kingham et al. 2001 ). Transport is the infrastructure of infrastructures (Pokharel and Acharya 2015 ) and is considered fundamental for urban development. The government of Nepal has prioritized the development of the transport sector. The main objective of the “National Transport Policy is to develop a reliable, cost-effective, safe, facility-oriented and sustainable transport system that promotes and sustains the economic, social, cultural and tourism development of Nepal as a whole” (National Transport Policy 2001 ). Chen and Chai ( 2011 ), using the theory of planned behavior, the technology acceptance model, and the concept of habit, studies the intentions of commuters to switch to public transit in Kaohsiung City, Taiwan, and finds that the habitual behavior of private vehicle users obstructs a commuter scheme to switch from private vehicles to public transit. JICA ( 2017 ) recommends the appropriate timing for the commencement of MRT system operation in Kathmandu, based on the introduction of mass transit systems in 24 Asian megacities and related to the gross income and population of the city. In each of these cases, the first MRT operation is launched when the respective city’s gross product is $3 to $30 billion. In the Kathmandu Valley, the population is projected to be four million, and per capita GDP will exceed US$ 900 by 2030. Thus, “based on experience in other Asian megacities, it shall be appropriate to introduce the 1st MRT system in the Kathmandu Valley between 2020 and 2030” (JICA 2017 , p. 122). Shrestha et al. ( 2013 ) finds that increasing vehicle speeds would reduce vehicle emissions, and that increasing urban mobility would improve the overall quality of life in the Kathmandu Valley. Das et al. ( 2018 ) states that technological change may play an important role in minimizing vehicular air pollution in Kathmandu. Ashalatha et al. ( 2013 ), applying multinomial logistics (MNL), finds various factors affecting particular modes of transport. In a case study in the city of Thiruvananthapuram, India, the main reason for shifting from buses to two-wheelers or cars is that the bus transport service is inefficient and unreliable. Jain et al. ( 2014 ) identifies reliability, comfort, safety, and cost as the main criteria for the modal shift from private vehicles to public transport, with Delhi as a case study. Using the pairwise weighing method (analytical hierarchy process), they find that safety is the most important criterion (36%), followed by reliability (27%), cost (21%), and comfort (16%). Lin and Guo ( 2015 ) studies the utility and weight of factors related to bus transit service quality in Nanjing, China, by applying conjoint analysis.

The private sector is responsible for almost 99% of the investment in public transport services in Nepal. There is no integrated policy for the management of public transport services. Government regulations and monitoring capacities are weak. Along with reducing the attraction of private vehicles, encouraging nonmotorized transportation and the use of public transport is an urgent agenda item for sustainable urban mobility. The solution to Kathmandu’s air pollution can be achieved only when the government takes the leading role in addressing the situation (Saud and Paudel 2018 ). For the effective implementation of such an intervention, it is best to know users’ preferences. This study examines the main attributes affecting commuters in the modal shift to public transport service in Kathmandu. Mass transit systems help to connect communities, support local economies, and improve the living standards of disadvantaged individuals. Therefore, a wide range of studies has been conducted in the field of public transport around the world. Researchers are constantly studying ways to improve public transport. They have focused mainly on the infrastructure sector, the behavioral sector, and the psychological sector. The current study is designed to understand the preferences of Kathmandu Valley commuters regarding the modern transport system before implementing future public transport policy, through a case study that provides a unique opportunity to investigate people’s perceptions of potential new services and their willingness to implement them.

The main objective of the choice-based conjoint experiment in this research is to examine the attributes affecting the choices and behaviors of commuters for improved public transport services in Kathmandu by answering the following questions: What factors are associated with commuters’ adoption of an improved public transport service?; Which attributes of the public transport service cause a modal shift?; How does each attribute affect the probability of various preferences?; What is the interaction with the passenger and the causal effect of the attribute? To answer these questions, we have generated attributes of hypothetical improved public transport services that have numerous external impacts on the surrounding environment.

2 Methodology

This experiment is carried out in Kathmandu, Nepal, where the main mode of mobility is road transport. Over the past decade, Kathmandu Valley has experienced rapid urbanization, high population growth, uncontrolled urban sprawl, and increased motorization, leading to problems with congestion, vehicular conflict, traffic accidents, environmental degradation, and poor public transport services. The government of Nepal plans to carry out various projects to improve the existing system. This study helps us to understand the preferences of commuters for improving public transport services in a very densely populated area.

For our study, the data are collected in two phases: the pilot survey and the main survey. The surveys are carried out within the periphery of the Ring Road, which is 27.3 km in length. For the study, we deliberately chose a list of 71 main stops and divide the city into four study areas by central main stop, and then separate the list of 71 stops into four zones . The main survey lasts 9 days and uses the paper-based street survey method. For the everyday survey, the authors prepare a random list of stops/streets in a randomly selected area using the Excel randomization function, from the selected list of stops with that value that connect to the Ring Road area (Fig. 1 ).

The Ring Road area is purposively selected based on four criteria: (1) it covers the central area of the city of Kathmandu; (2) it has connections to the Lalitpur and Bhaktapur districts; (3) it has a high population density; and (4) almost every commuter in Kathmandu Valley must use the Ring Road to get around the city. In the area selected for the study, all federal ministries and offices are situated in there, and the selected districts like Lalitpur and Bhaktapur are one of the most congested areas of Nepal. During the survey, we approached 400 commuters, and 373 commuters participated in our survey, with a response rate of 93.25%.

Conjoint analysis is used to study how buyers appreciate the characteristics of products or services and to predict buyer behavior (preference). It can be used to estimate the psychological trade-offs that commuters make when evaluating different attributes together. In this study, a randomized conjoint experiment is used to obtain the stated preferences of the respondents. In a conjoint experiment, the respondent evaluates profiles based on their attributes and levels, and then either chooses the option that gives them the highest utility or ranks the options. It is assumed that the respondent determines the overall utility by adding the utility provided by each attribute level. Through this experiment, we can determine the influence of each attribute level on the respondent’s choice (Hainmueller et al. 2014 ). While experimenting, we develop survey questionnaires with four parts: (1) information, (2) scenario, (3) choice-set of the randomized conjoint experiment, and (4) background information about the respondent, including age, sex, marital status, level of education, occupation, regional location, employment status, monthly income, the average monthly cost of commuting, vehicle ownership, main mode(s) of transport, typical usage time, and household members.

As suggested by Kløjgaard and Søgaard ( 2012 ), the attributes and levels relevant to the conjoint analysis of the public transport system are identified through quantitative methods. First, a literature search is conducted to identify the relevant attributes of public transport services from the commuters’ perspective. Second, a pilot survey is conducted among 28 commuters from different areas of Kathmandu City using a virtual interviewing method.

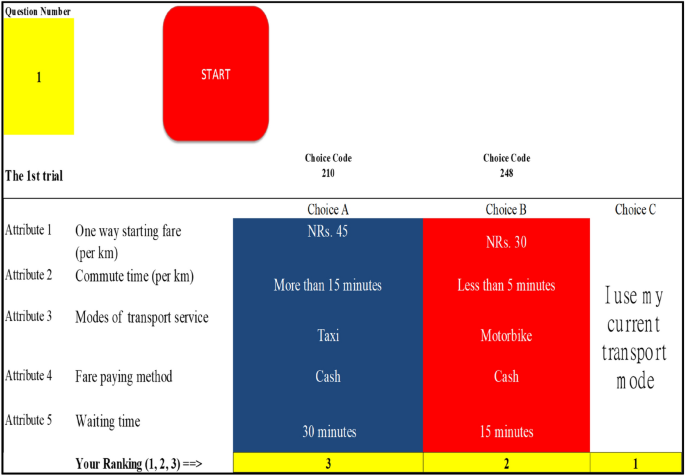

In this study, the randomized conjoint experiment consists of five attributes, each with two to five different levels. The attributes and levels of each choice profile are assigned randomly. Details of the attributes, levels, and baseline are shown in Table 1 . In the table, bold items in each attribute show baselines to compare with other levels, which means whether users prefer the level compared with the baseline level.

After reading the scenario, respondents are asked to consider three sets of choices—choice set (A), choice set (B), and choice set (C)—and then rank these 1, 2, and 3 based on their preference for enhanced public transport services. Each profile is designed with different alternatives. An example of the choice set is shown in Fig. 2 .

An example of the choice set

In this study, we try to identify commuters’ preferences for hypothetically improved public transport policies by estimating the probability of internal choice and external choice. Regarding internal probability, we estimate respondents’ preferences under two hypothetical alternative policies: choice (A) and choice (B), which means if there are only two choices like (A) and (B), which choice do you prefer? For external choice probability, we estimate respondents’ preference between the status quo and two alternative hypothetical policies. Each profile has three alternatives; from the left, the first two are hypothetical alternatives with five attributes and levels, and the third alternative is the status quo. The profile means that if there are three choices including the status quo (C), which choice do you prefer? These attributes are randomized for each respondent to avoid any possibility of an ordering effect. Similarly, to avoid cognitive strain, the order is randomized for all three profiles given to the same respondent. To estimate the probability of internal and external choice, we’re following the approach suggested by Hainmueller et al. ( 2014 ). These authors nonparametrically identify the average marginal component effect (AMCE) for each of the attributes and levels based on the probability of choosing a profile by randomized conjoint analysis. The attribute levels are assigned randomly, and ordinary least squares (OLS) are used to estimate the AMCE of each attribute as a coefficient based on a linear regression of the indicator of choice over the set of dummy variables for the attributes and levels. The model is as follows:

where the possible outcome of individual i in trial t of policy j is defined by \({\mathrm{y}}_{\mathrm{itj},}\) l stands for several attributes, and \({D}_{l}\) indicates the number of levels of each attribute l . \({\beta }_{ld}\) is the coefficient of each component to be estimated, \({\mathrm{a}}_{\mathrm{itjld}}\) is a dummy variable for the \(\mathrm{d}\) th level of policy \(j\) in task \(t\) of respondent \(i\) , and \({u}_{itj}\) ϵ {0,1} is an error term. In the internal choice probability estimation, \({y}_{itj}\) = 1 if the preference rank of policy j is higher than its alternative policy and 0 if the rank is smaller. Similarly, in the estimation of the external choice probability, \({y}_{itj}\) = 1 if the preference rank of policy j is higher than the status quo.

During the survey, some general information about the respondents is collected and analyzed. As Table 2 shows, the gender balance is nearly equal: 49.06% are female, and the rest are male. In terms of age, almost 69% of the respondents belong to the 17–40 years category, which represents the young adult population in Nepal. The highest proportion of our respondents (42.36%) has a university degree, followed by secondary education (34.05%), basic education (15%), and no literacy (8.56%). Similarly, 43.16% use public transport to get to work, 20.11% for school, 15.28% for grocery shopping, and 7.24% for leisure. In terms of vehicle ownership, 64% of the respondents have no vehicle, 16.62% have a motorbike, 11.8% have a car, and 2.68% have a bicycle. The respondents’ current travel mode is split between bus (47.45%), microbus (23.59%), motorbike (12.33%), minibus (9.12%), and tempo (auto-rickshaw) (3.75%).

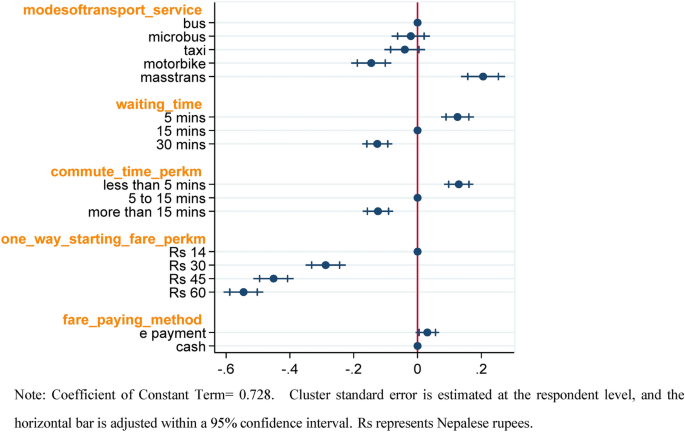

The average marginal component effect (AMCE) is the causal quantity of estimation using a pooled sample for external choice probabilities and internal choice probabilities. AMCE reflects the probability that profile (A) or (B) will be chosen by the respondent (Hainmueller et al. 2014 ). This survey also includes the status quo (C), which allows us to analyze a hypothetical proposal for improved public transport features based on the current Kathmandu public transport service. An airplane dot plot is used to show the corresponding coefficient on the X-axis, with the 95% confidence interval shown using horizontal bars, and the vertical axis shows the proposed attributes and their levels.

First, as a baseline, the most commonly used values for the public transport of each attribute level (written in italics and bold letters in Table 1 ) are used to compare Choice (A) and Choice (B), with the status quo (C), including to analyze the external probability. In the second part, we analyze the internal probability using a baseline the same as the external probability, and we compare the proposed hypothetical policies Choice (A) and Choice (B) only, without the status quo.

The probability of external choice shows that commuters accept the new and improved characteristics of the public transport service compared to the current situation (status quo). The constant term of the regression is 0.7288, which means that 73% of the respondents chose profile (A) or (B) rather than (C). The estimated average marginal treatment effect (AMCE) on external choice probability finds a significant impact for all attributes. The results show that the attributes with the highest impact on the probability of choosing a hypothetical policy are one-way starting fare and mode of transport.

As Fig. 3 shows, the first attribute, modes of transport, had five levels, with the baseline set to bus. However, the second level (microbus) and the third level (taxi) are not significant. The fourth level (motorbike) is negatively significant. Fourteen percent of the respondents do not like to use a motorbike as a form of transport. The fifth level (masstrans = MRT) is preferred over the baseline by 20%. This shows that commuters are eager to move from the current situation to a new public transport system. The second attribute, waiting time, has three levels: 5 min, 15 min, and 30 min. When we set 15 min as the baseline, a waiting time of 5 min has a positive impact probability of 12%, and a 30-min waiting time has a negative influence of − 12% when implemented. For the commute time (per km) attribute, 5–15 min is set as a baseline, and the level of few than 5 min has a positive impact of 12%, while the level of more than 15 min has a negative effect of − 12%, which means respondents do not like an increase in commute. The attribute one-way starting fare is the most influential key attribute in terms of external probability. If the new one-way starting fare is set to 60 Nepalese rupees (NRs), the probability of respondents taking the new public transport is negatively affected by − 54%, by − 45% when set to NRs 45, and by − 28% when set to NRs 30, which is useful information for developing a new policy. The fifth and last attribute, the fare payment method, has a significant effect. It comprised two levels: e-payment and cash. When we set cash as the baseline, the choice of e-payment has a positive impact of 3%, which means that respondents like to use e-payment.

Average causal effect on the external choice probability. Coefficient of Constant Term = 0.728. Cluster standard error is estimated at the respondent level, and the horizontal bar is adjusted within a 95% confidence interval. Rs represents Nepalese rupees

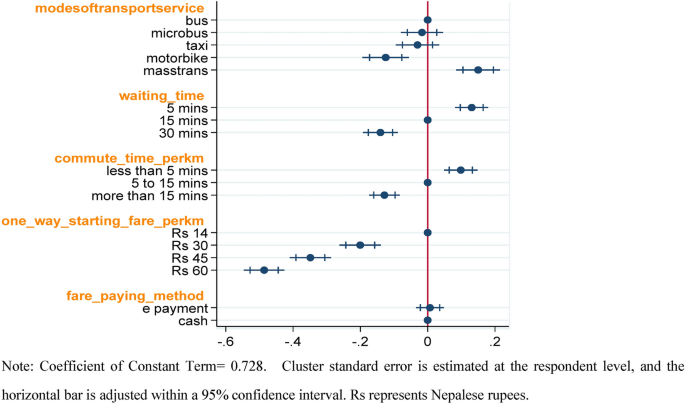

Also, as Fig. 4 indicates, the internal choice probability reveals respondents’ preference between the two proposed public transport improvement packages, package (A) and package (B). They prefer the improved service, which includes a mass transit system, less waiting, shorter commute times, and a lower fare per km. Although it improves the service, they do not care about the fare payment method. The first attribute, mode of transport, has five levels, with the baseline set to bus. However, the second level (microbus) and the third level (taxi) are not statistically significant. The fourth level (motorbike) is negatively significant, and 12% of the respondents do not like to use a motorbike for public transport. The fifth level (MRT) is preferred by 14% over the baseline. The second attribute, waiting time, has three levels: 5 min, 15 min, and 30 min.

Average causal effect on the internal choice probability. Coefficient of Constant Term = 0.728. Cluster standard error is estimated at the respondent level, and the horizontal bar is adjusted within a 95% confidence interval. Rs represents Nepalese rupees

Similar to Fig. 3 , for the waiting time, the 5-min waiting time increases the positive probability by 13%, and the 30-min level has a negative influence of − 4%. For the attribute commute time (per km), compared to 15 min, 5 min less has a positive impact of 9%, and 15 min more has a negative impact of − 12%. The one-way starting fare attribute is highly negatively significant with a level of NRs 30, NRs 45, and NRs 60 resulting in − 20%, − 34%, and − 48%, respectively.

To simplify the results above, a comparison of the results of both external and internal probability is summarized in Table 3 by picking some significant points up. For the probability of internal choice, we propose two hypothetical policies on improved public transport service based on the bundles of attributes and estimate the preference of respondents who answered the question, “Which is the most influential among the proposed policies? ” For the external choice probability, we include the status quo as an answer to the question, “Do we need a new proposed transport policy?” The result of the estimation shows that the preference trends are similar except for the fifth attribute; for the probability of internal choice, respondents do not care about the payment method. The comparative results of external and internal choice probability are presented.

4 Discussion

In the context of switching to a new public transport system, several attributes (mass rapid transit as the mode of transport, less waiting time, less commute time per km, and e-payment) had a clear influence on the approval of an improved system. However, commuters had negative feelings toward the use of motorbikes as public transport as well as toward increases in fare, waiting time, and commute time per km, and they did not prefer microbuses and taxis.

Due to the unreliable and inefficient nature of the public transport service, the use of two-wheelers, in particular motorbikes and scooters, has increased rapidly in the Kathmandu Valley, presenting a major challenge for maintaining sustainable urban mobility. This result confirms the JICA study, which stated: “At present, about 90% of buses in the Kathmandu Valley are low-occupancy vehicles, i.e., micro/minibusses. Smaller buses should be replaced by larger ones to operate the public transport system efficiently. The current transport network system of Kathmandu Valley is dependent on private vehicles and will not meet future demand; the introduction of a new public transport system, such as AGT or BRT, is recommended” (JICA, 2017 p. 114). Shrestha et al. ( 2013 ) claimed that low-speed buses and motorbikes were the main sources of emissions in the Kathmandu Valley. Moreover, our results support their finding that commuters are in favor of mass rapid transit.

From our results in Figs. 3 and 4 , we found that MRT, low fares, less waiting time, less commute time, and cashless payment methods are influential attributes promoting switching to public transport for nearly all commuters of different backgrounds. However, Jain et al. ( 2014 ) found that safety is the most important criterion for encouraging urban commuters to shift from private vehicles to public transit, followed by reliability, cost, and comfort. Chen and Chao, ( 2011 ) concluded that the habitual behavior of private vehicle users somewhat hindered individual intent to switch from private vehicles to mass rapid transit. In this study, individual characteristics, such as gender, vehicle ownership, sense of security of the current public transport system, and level of education, may affect modal shifts from private to mass transit differently. Ashalatha et al. ( 2013 ), in their study of the mode choice behavior of commuters in the city of Thiruvananthapuram, India, found that the preference for a car increases with increasing age, while the preference for two-wheelers decreases. Therefore, the switch from private vehicles to public transit depends upon time per distance and cost per distance. The results of a subsample analysis using the background information in this study supported their findings. In a case study of the city of Kalamaria, Greece, commuters placed importance on the attribute of comfort, followed by fare, information provision, and accessibility to a transit network (Tyrinopoulos and Antoniou 2013 ). However, commuters gave comfort (i.e., MRT and negative views of motorbikes) and fare almost equal preference in Kathmandu. Likewise, IBN ( 2017 ) proposed investments in mass transit system projects, i.e., MRT, LRT, BRT, flyovers, and tunnelway systems, for the sustainable mobility of the Kathmandu Valley. This study empirically outlined the effective implementation of proposed mass rapid transit projects in Kathmandu Valley. However, Pathao and Tootle have been using motorbikes and scooters as public transport in Kathmandu since 2018. Legal provisions do not allow the use of two-wheelers as a public transportation service in Nepal. According to the Motor Vehicles and Transport Management Act of 1993, commercial vehicles must obtain a permit to operate and must have registered their public transport service in the DoTM; however, Pathao and Tootle have been operating two-wheelers without registering with the transport service, which is illegal (OAGNEP 2020 p. 304). Motorbikes are the main cause of traffic congestion, air pollution, and road accidents (Shrestha et al. 2013 ). The results of this study confirm that respondents are not in favor of two-wheelers in the city of Kathmandu.

Azimy et al. ( 2020 ) found that acceptance probability of proposed saffron production promotion policies in Herat Province, Afghanistan, which support to change the current policy of transport system. The improvement of the current public transport system is the most important and urgent agenda item for the overall development of the country. Although the government has made efforts to improve the public transport service sector in Kathmandu, these efforts have not been effective. The weak capacity and authority of the regulatory body, scarce resources, weak policy enforcement, and the low participation of stakeholders are the main problems for sustainable implementation.

Both Figs. 3 and 4 indicate that commuters are in favor of a new improved public transport system. It implies while formulating a new policy, it would be best to focus on the introduction of MRT with the e-payment method for public transport services, and to consider low fares or other schemes, such as monthly or yearly ticketing or family packages, to motivate commuters to embrace the new system. Public transport should run on a timely basis, which would enhance commuters’ trust in addition to their comfort and the price. This study also envisages the effective implementation of the BRT project on the Ring Road in Kathmandu, proposed by the IBN, and recommends applying the minimum fare with the cashless payment method. Referring to the subsample analysis, commuters whose permanent residence is outside of Kathmandu Valley also preferred MRT, which shows that MRT is the best means of transport for urban mobility in other large cities as well.

5 Conclusion

This study has focused on examining commuters’ preferences for improved public transport services in Kathmandu Valley. A choice-based conjoint experiment was conducted that included five attributes and 17 levels, all of which may affect commuter preference in terms of switching to public transport.

Now, we can answer our research questions set up in the introduction part according to our results:

First, commuters are strongly interested in changing current transport services including a public one like a bus to a new type of public transport service like MRT, considering cost and time. They are in favor of a modal shift to mass rapid transport and against motorbikes. However, introducing the MRT to the region must usually be costly so financial support like ODA would be necessary to overcome budget constraints. This budget matter is not within the scope of this study, but independently it should be considered.

Second, concretely using attributes such as waiting time for the service, commuting time, service fare, payment method as well as the type of transport service, all five attributes had the expected significant impact on the intention to switch to a new mass transit service. The most significant attributes are one-way fare per km and the mode of transport. They are strongly against increases in the current fare, waiting time, and commute time. Meanwhile, they prefer to switch from cash to e-payment.

Third, however, the improved public service of the bus has been likely to be selected by many commuters. According to our results of choice probability, about 73% of commuters showed their expectations toward a new or improved public transport service.

This case study has focused on an area with high traffic congestion and its suburbs. The results will support transport planners in formulating and implementing an effective transport policy that takes people’s preferences into account. Especially, a massive rapid transit system with a low fare would be highly welcome in a typical congestion area like Kathmandu.

Meanwhile, focusing on one area is a limitation of this study. The congestion problem is very common and serious in many developing countries. Many empirical studies based on the causal inference approach are strongly expected further in other regions and countries as well.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ashalatha R, Manju VS, Zacharia AB (2013) Mode choice behavior of commuters in Thiruvananthapuram City. J Transport Eng 139:494–50. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)TE.1943-5436.0000533

Article Google Scholar

Azimy MW, Khan GD, Yoshida Y, Kawata K (2020) Measuring the impacts of saffron production promotion measures on farmers’ policy acceptance probability: a randomized conjoint field experiment in Herat Province Afghanistan. Sustainability 12:4026. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104026

Bajracharya AR, Shrestha SJ (2017) Analyzing influence of socio-demographic factors on travel behavior of employees, a case study of Kathmandu Metropolitan City, Nepal. Int J Sci Technol Res 6:111–119

Bhattarai K, Yousef M, Greife A, Lama S (2019) Decision-aiding transit-tracker methodology for bus scheduling using real time information to ameliorate traffic congestion in the Kathmandu Valley of Nepal. J Geogr Inf Syst 11:239–291

Google Scholar

CBS (2013) Central Bureau of Statistics, Government of Nepal. Available online: www.cbs.gov.np . Accessed 5 Feb 2019

Chen C-F, Chao W-H (2011) Habitual or reasoned? Using the theory of planned behavior technology acceptance model, and habit to examine switching intentions toward public transit. Transp Res Part F 14:128–137

Das B, Bhave PV, Puppala SP, Byanju RM (2018) A Global perspectives of vehicular emission control policy and practices: an interface with Kathmandu valley case, Nepal. J Inst Sci Technol 23:76–80

Dhakal S (2006) Urban transport and the environment in Kathmandu valley: integrating global carbon concerns into local air pollution management. First, Retrieved June 2020. Available online: https://www.iges.or.jp/en/publication_documents/pub/policyreport/en/449/iges_start_final_reprot.pdf . Accessed 10 Feb 2020

DoTM (2019) Department of Transport management. Vehicle Registration Statistic Department of Transport Management, Government of Nepal, Kathmandu. Available online: www.dotm.gov.np . Accessed 16 Feb 2020

Global mobility report (2017) Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/2643Global_Mobility_Report_2017.pdf . Accessed 9 Jan 2020

Hainmueller J, Hopkins DJ, Yamamoto T (2014) Causal inference in conjoint analysis: understanding multidimensional choices via stated preference experiments. Polit Anal 22(1):1–30

IBN (2017) Investment Board Nepal, Government of Nepal. Transportation Sector Profile of Investment Board Nepal. Available online: https://ibn.gov.np/transportation/ . Accessed 28 Dec 2019

ICIMOD (2017) International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, The status of glaciers in the Hindu Kush-Himalayan region. https://doi.org/10.1659/mrd.mm113 . Accessed 5 Dec 2019

Jain S, Aggarwal P, Kumar P, Singhal S, Sharma P (2014) Identifying public preferences using multi-criteria decision making for assessing the shift of urban commuters from private to public transport: a case study of Delhi. Transp Res Part F 24:60–70

JICA (2017) Japan International Cooperation Agency. The Project on Urban Transport Improvement for Kathmandu Valley in Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal Final Report May 2017. Available online: https://openjicareport.jica.go.jp/pdf/12289674.pdf . Accessed 18 Mar 2020

Kingham S, Dickinson J, Copsey S (2001) Traveling to work: will people move out of their cars. Transp Policy 8(2):151–160

Kløjgaard M, Bech M, Søgaard R (2012) Designing a stated choice experiment: the value of a qualitative process. J Choice Model 5(2):1–18

KSUTP (2014) Kathmandu sustainable urban transport project, public transport restructuring. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/370110066/Public-Transport-Restructuring . Accessed 27 Apr 2019

KSUTP (2016) Kathmandu sustainable urban transport project. A sustainable transport project status and progress 2016, Presentation slides.

Lin J, Guo T (2015) Utility and weight of factors of bus transit’s service quality analysis in Nanjing. J Harbib Inst Technol 22(3):115–122. https://doi.org/10.11916/j.issn.1005-9113.2015.03.017

MoPIT (National Transport Policy) (2001) Vision paper, National environment transport Strategy 2025–2040. Available online: www.mopit.gov.np . Accessed 20 May 2020

MoUD (2017) Ministry of urban development, national urban development strategy, 2017. Available online: www.moud.gov.np . Accessed 2 July 2020

OAGNEP (2020) Office of auditor general, 57th annual report of auditor general, 2020 Available online: https://oagnep.gov.np . Accessed 15 July 2020

Pokharel R, Acharya SR (2015) Sustainable transport development in Nepal challenges, opportunities and strategies. J East Asia Soc Transp Stud 11:209–226. https://doi.org/10.11175/easts.11.209

Saud B, Paudel G (2018) The threat of ambient air pollution in Kathmandu, Nepal. J Environ Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1504591

Shrestha SR, Oanh NTK, Xu Q, Rupakheti M, Lawrence MG (2013) Analysis of the vehicle fleet in the Kathmandu valley for estimation of environment and climate co-benefits of technology intrusions. Atmos Environ 81:579–590

Tyrinopoulos Y, Antoniou C (2013) Factors affecting modal choice in urban mobility. Eur Transp Res Rev 5:27–39

The World Bank (2017) Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/transport/overview . Accessed 2 July 2020

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to really thank the anonymous referees’ comments to improve this paper. However, if some mistakes were left, it is our responsibility.

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Transport Management, Minbhawan, Kathmandu, Nepal

Tulsi Ram Aryal

International Economic Development Program, Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Center for Peaceful and Sustainable Futures (CEPEAS), IDEC Institute, and Network for Education and Research On Peace and Sustainability (NERPS), Hiroshima University, Higashihiroshima, Hiroshima, 739-8529, Japan

Masaru Ichihashi & Shinji Kaneko

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Execution of experimental work and preparation, TRA; conceptualization, TRA, and MI; programming, SK, and MI; software, TRA, and MI; writing—original draft preparation, TRA; writing—review and editing, MI; supervision, MI All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Masaru Ichihashi .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Aryal, T.R., Ichihashi, M. & Kaneko, S. How strong is demand for public transport service in Nepal? A case study of Kathmandu using a choice-based conjoint experiment. Economic Structures 11 , 29 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40008-022-00287-3

Download citation

Received : 12 April 2022

Revised : 10 November 2022

Accepted : 11 November 2022

Published : 08 December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40008-022-00287-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- B360 National

- International

- In the Lead

- People To Watch

- Business Sutra

- Legal Eagle

- Guest Column

- Management Sutra

- The Big Picture

- Ringside View

- Face 2 Face

- Commodity Perspective

- Through the Mystic Eye

- B360 Exclusive

- Editorial Page

- Photo Gallery

- E-Magazines

Public Transportation Issues, Challenges and way forward

The road network of Kathmandu Valley is around 1800 kms where 700,000 vehicles run every day. In developing countries like Nepal, people strongly believe that the public transport is for poor. Such belief is one of the major causes for the exponential increment of private vehicle ownership in Kathmandu in recent years. The increase of motorised vehicles is around 20% annually.

Owning private vehicles is perceived as a status symbol in Nepal. International experiences have shown that such perception needs to be changed and will change given that safe, cheap reliable, secure and comfortable public transportation is operated

Dwellers of Kathmandu are facing mobility problems for years. Currently, traffic congestion and safety have become public concern. People suffer severely from traffic congestion and road accidents. Annually 2200 people lose their lives on roads. The situation is worsening by the day.

The government has put focus on widening of roads to solve traffic issues in the valley leaving the issue of sustainable public transportation development in the shadow. Examples of world class cities have demonstrated that traffic issues cannot be solved only through expanding road infrastructure. Nepal needs a strategy shift from road widening to implementation of proper public transportation. The best way to achieve sustainable transport management would be an integrated program of developing public transport systems and road widening simultaneously.

Land is a scarce resource and its use is limited. Therefore, road widening cannot be carried out again and again whenever a city experiences traffic congestion. The current widening of roads in the may ease traffic for some years, but the numbers are on the rise. Once demand exceeds the capacity of roads, the situation will recur.

There is no possibility to widen roads infinitively. Therefore, Nepal needs to learn from the experiences of other cities to promote public transportation systems immediately. Public transport has the capacity to solve the challenges of increasing mobility, improve quality of life, control road and traffic accidents. Nepal is in strong need of a public transport system that is safe, secure, reliable, integrated, smooth, comfortable, economical, efficient and affordable. Once the level of service of public transport reaches close to that of private vehicles, people will automatically make the shift.

The government has already implemented regulations to restrict private vehicle through high vehicle registration charges, environmental charges, fuel taxes and parking charges. This makes access to private vehicle ownership expensive and unaffordable to all.

Currently there is mix of traffic on the roads of Kathmandu with high capacity public buses (56 seater) to low capacity (12 seater) micro buses. The trunk routes are wider so high capacity buses should ply on these routes with low capacity ones on feeder routes. Currently, availability of public transport in day time is not a big issue but the concerns are of reliability, safety, security, connectivity and comfort. Social as well as economic activities will enhance only once a city has well developed transportation systems.

Transport operators need to be financially sustainable from the service fee. Therefore, they focus on revenue maximisation rather than service. Public transport is a business. This is a contradiction which needs to be balanced. In the current scenario, no operator will run an empty vehicle as a public service, they will accommodate as many passengers as they can, often running on erratic schedules. A 12 seater micro bus can be seen carrying 20 people or more and a bus keeps waiting till it gets sufficient passengers.

When government can spend millions of rupees to widen roads, it is well capable of investing in developing sustainable public transport systems. The sustainability will also depend largely on public and private partnership outcomes.

A bus service for the night was implemented in Kathmandu on a trial basis in 2069 BS. It was operated from 8pm to 11pm in Kathmandu valley and was inaugurated by then deputy prime minister at Shanti Vatika, Ratnapark. It was operated for six months on trial and subsidy of Kathmandu Metropolitan City and Ministry of Finance. Fourteen night buses were operated in five different routes in the inner city and one more route on the ring road. 26-seater capacity buses equipped with CCTV and two armed security personnel were assigned to 4 to 6 trips on respective routes per day. The fare maintained was same as that in day time.

KMC provided 2.5 million rupees and the Finance Ministry provided two million rupees for operation of the night bus service for the first six months as fuel cost and wages subsidy to private operators. It was agreed that private operators after six months would operate without subsidy but it couldn’t happen. Each bus collected on average Rs 500-700 on the first trip, but after that, there were minimal number of passengers. Economic sustainability of the night bus service was impossible which resulted in the shutdown of the service.

The government now has the opportunity to improve the transportation system as syndicate in the public transportation sector, prevalent for the last three decades has come to an end. The government needs to plan well on issues such as route permits, capacity of vehicles, departure timing, ticket pricing, integration of time table and ticketing system among others. It needs to ensure scientific and systematic public transport management. All transport operators must register themselves under the company act and come under a single umbrella.

Government involvement in transport operation authority is also required for smooth functioning of public transportation. This is a practice worldwide. In Munich Germany, Munich Transport Authority has been established through shareholding from state government, Munich City, eight administrative districts and 40 public transport companies. All the public transportation (metro rail, bus, tram) are operated through a coordinated system. Similarly, in Berlin, the Berlin Transport Company was established in 1992 with the municipality integrating public and private transport operators. In Delhi, the government owned Delhi Transportation Corporation runs public transportation.

The government needs to expedite the process of registration of current transport committees as companies and work alongside to setting up a transport authority and bring all operators under this authority. This authority must be granted the sole responsibility to plan and operate public transportation. Any investment in the public transport sector can be routed through this authority. This model should be replicated in all major cities of the country. This authority will be led by a Chief Executive Officer with required technical and administrative staffs. Investors will be the board of directors with CEO holding executive power.

To make this authority sustainable and profitable, the government should be ready to subsidise expenses. For instance, in Germany, Italy, Netherlands and Belgium, the government gives subsidy up to 40%, 60%, 60% and 67% respectively.

In recent years, some public transport operating companies like Sajha Yatayat, Mahanagar Yatayat and Mayur Yatayat have been providing comparatively improved urban transport services. Sajha Yatayat has been operating in the cooperative model with involvement of Kathmandu Metropolitan City as a major shareholder. The government now needs to implement 24 hour bus service programs in urban cities like Kathmandu, Pokhara, and Biratnagar.

The population of Kathmandu has already exceeded five million. To manage transportation system in Kathmandu, urban railways has become essential. Principally, a city with more than three million population requires urban railways to manage urban transportation issues. Investment Board Nepal (IBN), a government entity has also initiated developing a metrorail system from Dhulikhel to Nagdhunga. Currently IBN is in the process of selecting a consulting firm to conduct a detailed feasibility study. The Kathmandu Metropolitian City has also permitted a private Chinese company to conduct feasibility study of monorail system on the Ring Road. Considering the population size, Kathmandu Valley needs metrorail system not monorail system. Metrorail system has the capacity to move 85,000 passengers per hour per direction but monorail system only 30,000. Urban railway system will help reduce traffic congestion, emission and improve road safety. Since urban railway projects are in the study phase, it will take more than eight years to come into operations if at all. Therefore, there is no immediate alternative to developing a public bus system in the immediate conditions.

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) could be operated immediately on the recently widened ring road and other trunk roads, high-capacity buses on trunk routes and smaller vehicles on narrower roads.Government must immediately initiate a public transport company for Kathmandu valley and initiate getting all the current public transport companies under this authority. All companies will be promoters of this authority based on shares that are calculated on the number of buses they own. The authority will have control on planning, staffing, routing, ticketing and scheduling, etc. The first phase must concentrate on institutionalisation of the authority and development of integrated ticketing system and schedules. The state must define standards of service that the authority must deliver.

By Ashish Gajurel, Transport and Traffic Engineer

Click Here To Read Full Issue

The dismal reality of business investment, the ev market pros & cons, the cost of disasters and what can be done, npl of commercial banks surge exponentially, privacy policy.

My experience using public transport in Nepal

Farhad ahmed.

Transport is a means to an end, not an end in itself. We use transport to access facilities and services - jobs, educational institutions, health facilities, banks etc. Quality and availability of public transport make an impact on the welfare and income earning potential of people. Good quality and targeted public transport also helps in pulling people away from cars. Intensive public transport use not only contributes to people’s welfare but also helps enhance urban environment. For women in developing countries, public transport plays an even more important role, providing access to social, economic and life enriching activities and services. In the above context, cities in Nepal need safe, efficient, reliable and affordable public transport to achieve equitable and sustainable development. The World Bank in Nepal is working with the government of Nepal to develop a National Transport Management Strategy. The strategy will address issues linked to broader transport management, as well as gender and public transport related issues. Findings from the recent gender and transport study is being incorporated into the National Strategy so that the various issues the women and men of Kathmandu face while using public transport will be effectively addressed in the coming days. Read the recently released report: Gender and Public Transport in Nepal Photo: Dee Jupp/World Bank

- Urban Development

Senior Transport Specialist

Join the Conversation

- Share on mail

- comments added

- Covid Connect

- Entertainment

- Science&Tech

- Environment

PM extends best wishes on Bijaya Dashami festival

Over 31,000 foreign tourists visit ghodepani last year, pm dahal appoints pandey as youth and social development expert.

- Sudur Pashchim

Public transportation problems

Sandeep sen.

With the growing population density of the Valley, commuting in public vehicles to reach one’s destination has become an unpleasant experience filled with discomfort for commuters. While problems like over-crowded public vehicles, lack of proper operating schedule and bus stops, uncomfortable rides and untimely services among others continue to plague the Capital’s public transportation system, ensuring safe, timely and quality public transportation facilities for Valley’s citizens has become the need of the hour.

According to the National Census (2011), Kathmandu has the largest population of 1,744,240 in Nepal with an average annual growth rate of 4.78 per cent while the statistics of the Department of Transport Management (DoTM) of the fiscal year 2016/17 shows the total number of vehicle registrations to be 119,956 in Bagmati zone which includes 1,405 buses, 2,132 minibuses, 14,542 cars and jeeps, 222 microbuses and 94,751 motorcycles.

The statistics are evidence of the fact that while the population density of the Capital and trend of private vehicle ownership is increasing rapidly, the gap between private and public vehicle ownership continues to increase, cementing the fact that the current state and number of public vehicles operating in the Valley is not adequate to serve public transportation consumers.

PASSENGER WOES

For Shristi Maharjan, a resident of Siddhipur, who usually travels from Siddhipur to New Road, waiting for a lengthy period of time to catch a public vehicle has become a habit. She says, “I am usually working till five or six in the evening and it’s difficult to get a bus during the evening hours. There are usually so many people waiting for the same bus and when it finally arrives, everyone tries to get in at once because of which getting a comfortable seat for a comfortable ride in public transportation has become a distant dream.”

On top of that, Maharjan shares that the bus drivers and conductors keep trying to fit more people than the vehicle’s capacity during peak hours — mostly during mornings and evenings which adds to passengers’ discomfort.

Bhushan Tuladhar, CEO, Sajha Yatayat, shares, “The condition of public transportation at present is chaotic and there is a lot that needs to be improved.”

He adds, “Private transport entrepreneurs have invested a lot in public transportation sector but still proper monitoring and regulation on the part of the government is inadequate which has stunted the quality of service that the private sector is providing.” Currently, Sajha Yatayat operates 71 public buses in the Valley but Tuladhar feels that despite adding new vehicles on various routes, the company has not been able to meet the demand of public buses on many of its bus routes.

Saroj Sitaula, General Secretary at Federation of Nepali National Transport Entrepreneurs, shares, “The public transportation sector is degrading day by day and the major problems that have led to its dilapidation are inefficient and unclear rules and regulation, lack of banking facilities and investment security for transport entrepreneurs among others. “There is a lack of public vehicles for the public which needs to be increased to facilitate commuters.”

BREAKING SHACKLES OF SYNDICATE

Last year, the government launched a strict crackdown against the syndicate system, which was prominently prevalent in the public transportation sector of Nepal for long.

Tirtha Raj Khanal, Information Officer at DoTM, says, “Prior to the crackdown on public transportation syndicate system, anyone seeking route permit in the Valley would require a formal recommendation from transport entrepreneur associations and federations even though according to the law, the practice was not a prerequisite.

And this informal practice had been going on for years.”

He adds, “Now, DoTM can issue route permits in accordance to the necessity and demand of the public, which we believe will ease public transportation services.”

As per him, earlier, transport entrepreneurs held the monopoly to decide if new transport entrepreneurs were to be allowed to operate their vehicles on the roads or not. Also, departure timings, number of vehicles for operations and routes were decided by the transport entrepreneurs autonomously. Under the new system, transport bodies, associations and federations also formally announced their shift to company modality on July 19 ensuring public transportation sector’s healthy growth and officially bringing monopoly on the public transportation sector to an end.

Sitaula informs, “As directed by the government, the majority of transport entrepreneurs have transformed and still continue to transform into private companies.”

Bishnu Prasad Timilsina, Deputy General Secretary at Forum for Protection of Consumers’ Right Nepal (FPCRN) shares, “The authorities and transport entrepreneurs feel that introducing company modality and following it has formally ended the syndicate system but that is not true. In the coming days it is highly likely that transport companies will impose similar monopoly system under the company modality and it is vital that the government stops all ill practices related to the syndicate system.”

“We feel that the consumers should get timely service and public vehicles in accordance to commuter’s density should be available. It is the government’s responsibility to manage public transportation system but it has not been able to neither manage nor monitor the public transportation sector because of which consumers continue to face problems,” he shares.

THE WAY OUT

Sitaula shares, “In order to make Nepal’s public transportation sector convenient for people, the government should consult every stakeholder and make transportation regulations and operating systems. The government should also come up with ways of decreasing road accidents while ensuring that victim get compensated for the loss.” He adds, “If the government doesn’t ensure investment and professional security to transport entrepreneurs along with consumer’s security, investment from private sector’s side in the public transportation sector will not increase which will further degrade the sector.”

Tuladhar feels that to tackle the problem of overcrowding of public vehicles, a public standard needs to be maintained while keeping quality of service and affordability in mind. He says, “I feel that there are adequate number of public vehicles in the country but the sector lacks systematic and regular vehicular frequency which has created problems for the public.”

As per him, the increasing trend of introducing big buses has also been beneficial to improve public transportation network.

He shares, “Around six years ago, our transportation system was mainly dominated by small vehicles and big vehicles are being introduced so that it can accommodate many people at once. Having said that, big vehicles cannot operate on every part of the road network and a combination of both small vehicles like microbuses and big vehicles like buses are necessary.”

He adds, “Since private sectors are a huge part of public transportation sector, the government must take their interests into consideration while moving forward. In addition to that the government should also invest in public transportation services and work towards modernising it.”

Timilsina believes that it is essential for the government to create a separate authority which looks after public transportation systems — where queries and complaint related to public transportations are entertained while regularly carrying out efficient monitoring activities.

He says, “Currently, FP- CRN has been conducting studies on the public transportation system of Nepal so that we can identify its drawbacks.”

Khanal shares that in order to improve public transportation system and ease traffic congestion, DoTM is currently conducting a research to add new routes to the transport network. He adds, “We also have plans to systemise existing bus parks in the Valley.”

Slow capital spending irks FinMin Paudel

Next Article

- Privacy Policy

- Advertise With Us

© 2021 The Himalayan Times

- Year 2023 Volume 35_1&2

- Year 2022 Volume 34_2

- Year 2022 Volume 34_1

- Year 2021 Volume 33_1&2

- Year 2020 Volume 32-2

- Year 2020 Volume 32-1

- Year 2019 Volume 31-2

- Year 2019 Volume 31-1

- Year 2018 Volume 30-2

- Year 2018 Volume 30-1

- Year 2017 Volume 29-2

- Year 2017 Volume 29-1

- Year 2016 Volume 28-2

- Year 2016 Volume 28-1

- Year 2015 Volume 27-2

- Year 2015 Volume 27-1

- Year 2014 Volume 26-2

- Year 2014 Volume 26-1

- Year 2013 Volume 25-2

- Year 2013 Volume 25-1

- Year 2012 Volume 24-2

- Year 2012 Volume 24-1

- Year 2011 Volume 23-2

- Year 2011 Volume 23-1

- Year 2010 Volume 22

- Year 2009 Volume 21

- Year 2008 Volume 20

- Year 2007 Volume 19

- Year 2006 Volume 18

- Year 2005 Volume 17

- Year 2004 Volume 16

- Year 2003 Volume 15

- Year 2002 Volume 14

- Year 2001 Volume 13

- Year 2000 Volume 12

- Year 1999 Volume 11

- Year 1998 Volume 10

- Year 1997 Volume 9

- Year 1995 Volume 8

- Year 1994 Volume 7

- Year 1992 Volume 6

- Year 1991 Volume 5

- Year 1990 Volume 4

- Year 1989 Volume 3

- Year 1988 Volume 2

- Year 1987 Volume 1

Prof. Dr. Parashar Koirala