- Request new password

- Create a new account

Writing a Research Paper in Political Science: A Practical Guide to Inquiry, Structure, and Methods

Student resources, welcome to the companion website.

Want your students to write their first major political science research paper with confidence? With this book, they can. Author Lisa Baglione breaks down the research paper into its constituent parts and shows students precisely how to complete each component. The author provides encouragement at each stage and faces pitfalls head on, giving advice and examples so that students move through each task successfully. Students are shown how to craft the right research question, find good sources and properly summarize them, operationalize concepts, design good tests for their hypotheses, and present and analyze quantitative and qualitative data. Even writing an introduction, coming up with effective headings and titles, presenting a conclusion, and the important steps of editing and revising are covered with class-tested advice and know-how that’s received accolades from professors and students alike. Practical summaries, recipes for success, worksheets, exercises, and a series of handy checklists make this a must-have supplement for any writing-intensive political science course.

In this Third Edition of Writing a Research Paper in Political Science , updated sample research topics come from American government, gender studies, comparative politics, and international relations. Examples of actual student writing show readers how others "just like them" accomplished each stage of the process.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Lisa Baglione for writing an excellent text and developing the ancillaries on this site.

For instructors

Access resources that are only available to Faculty and Administrative Staff.

Want to explore the book further?

Order Review Copy

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Writing a Research Paper in Political Science A Practical Guide to Inquiry, Structure, and Methods

- Lisa A. Baglione - Saint Joseph's University, USA

- Description

Even students capable of writing excellent essays still find their first major political science research paper an intimidating experience. Crafting the right research question, finding good sources, properly summarizing them, operationalizing concepts and designing good tests for their hypotheses, presenting and analyzing quantitative as well as qualitative data are all tough-going without a great deal of guidance and encouragement. Writing a Research Paper in Political Science breaks down the research paper into its constituent parts and shows students what they need to do at each stage to successfully complete each component until the paper is finished. Practical summaries, recipes for success, worksheets, exercises, and a series of handy checklists make this a must-have supplement for any writing-intensive political science course.

New to the Fourth Edition:

- A non-causal research paper woven throughout the text offers explicit advice to guide students through the research and writing process.

- Updated and more detailed discussions of plagiarism, paraphrases, "drop-ins," and "transcripts" help to prevent students from misusing sources in a constantly changing digital age.

- A more detailed discussion of “fake news” and disinformation shows students how to evaluate and choose high quality sources, as well as how to protect oneself from being fooled by bad sources.

- Additional guidance for writing abstracts and creating presentations helps students to understand the logic behind abstracts and prepares students for presentations in the classroom, at a conference, and beyond.

- A greater emphasis on the value of qualitative research provides students with additional instruction on how to do it.

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

Supplements

“ Writing a Research Paper in Political Science is a helpful research and writing guide for students from various disciplines and undergraduate levels.”

“Lisa A. Baglione’s book is a highly accessible resource to help undergraduate students transition from writing about politics to writing about empirical political science research.”

“With clarity and compassion, Lisa A. Baglione leads undergraduates step by step through the morass of empirical research.”

“ Writing a Research Paper in Political Science is an essential text for every political science major.”

This is an engaging and well written book that seems geared to the level of the course - students writing their senior capstones.

Excellent, in-depth review of how to do a research paper. Perfect for learning objectives of my course.

too focused on political science, not a good fit for urban planning.

NEW TO THIS EDITION:

- A non-causal research paper woven throughout the text offers explicit advice to guide students through the research and writing process.

- Updated and more detailed discussions of plagiarism, paraphrases, “drop-ins,” and “transcripts” help to prevent students from misusing sources in a constantly changing digital age.

- A more detailed discussion of “fake news” and disinformation shows students how to evaluate and choose high quality sources, as well as how to protect oneself from being fooled by bad sources.

- Additional guidance for writing abstracts and creating presentations helps students to understand the logic behind abstracts and prepares students for presentations in the classroom, at a conference, and beyond.

- A greater emphasis on the value of qualitative research provides students with additional instruction on how to do it.

KEY FEATURES:

- End-of-chapter recipes for annotated bibliographies, literature reviews, thesis formation, and more guides students step-by-step as they navigate common issues when composing a research paper.

- Practical summaries , located at the end of each chapter, guide students towards their goals.

- Sample material from student papers help illustrate in detail how students can craft and revise their content.

- A natural progression of chapter topics guides students from finding a research question and distilling arguments, to revision and proper citation.

Preview this book

Sample materials & chapters.

CHAPTER 1: So You Have to Write a Research Paper

CHAPTER 3: Learning Proper Citation Forms, Finding the Scholarly

For instructors

Select a purchasing option.

Shipped Options:

BUNDLE: Van Belle, A Novel Approach to Politics 6e (Paperback) + Baglione, Writing a Research Paper in Political Science 4e (Paperback)

Political Science

What this handout is about.

This handout will help you to recognize and to follow writing standards in political science. The first step toward accomplishing this goal is to develop a basic understanding of political science and the kind of work political scientists do.

Defining politics and political science

Political scientist Harold Laswell said it best: at its most basic level, politics is the struggle of “who gets what, when, how.” This struggle may be as modest as competing interest groups fighting over control of a small municipal budget or as overwhelming as a military stand-off between international superpowers. Political scientists study such struggles, both small and large, in an effort to develop general principles or theories about the way the world of politics works. Think about the title of your course or re-read the course description in your syllabus. You’ll find that your course covers a particular sector of the large world of “politics” and brings with it a set of topics, issues, and approaches to information that may be helpful to consider as you begin a writing assignment. The diverse structure of political science reflects the diverse kinds of problems the discipline attempts to analyze and explain. In fact, political science includes at least eight major sub-fields:

- American politics examines political behavior and institutions in the United States.

- Comparative politics analyzes and compares political systems within and across different geographic regions.

- International relations investigates relations among nation states and the activities of international organizations such as the United Nations, the World Bank, and NATO, as well as international actors such as terrorists, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and multi-national corporations (MNCs).

- Political theory analyzes fundamental political concepts such as power and democracy and foundational questions, like “How should the individual and the state relate?”

- Political methodology deals with the ways that political scientists ask and investigate questions.

- Public policy examines the process by which governments make public decisions.

- Public administration studies the ways that government policies are implemented.

- Public law focuses on the role of law and courts in the political process.

What is scientific about political science?

Investigating relationships.

Although political scientists are prone to debate and disagreement, the majority view the discipline as a genuine science. As a result, political scientists generally strive to emulate the objectivity as well as the conceptual and methodological rigor typically associated with the so-called “hard” sciences (e.g., biology, chemistry, and physics). They see themselves as engaged in revealing the relationships underlying political events and conditions. Based on these revelations, they attempt to state general principles about the way the world of politics works. Given these aims, it is important for political scientists’ writing to be conceptually precise, free from bias, and well-substantiated by empirical evidence. Knowing that political scientists value objectivity may help you in making decisions about how to write your paper and what to put in it.

Political theory is an important exception to this empirical approach. You can learn more about writing for political theory classes in the section “Writing in Political Theory” below.

Building theories

Since theory-building serves as the cornerstone of the discipline, it may be useful to see how it works. You may be wrestling with theories or proposing your own as you write your paper. Consider how political scientists have arrived at the theories you are reading and discussing in your course. Most political scientists adhere to a simple model of scientific inquiry when building theories. The key to building precise and persuasive theories is to develop and test hypotheses. Hypotheses are statements that researchers construct for the purpose of testing whether or not a certain relationship exists between two phenomena. To see how political scientists use hypotheses, and to imagine how you might use a hypothesis to develop a thesis for your paper, consider the following example. Suppose that we want to know whether presidential elections are affected by economic conditions. We could formulate this question into the following hypothesis:

“When the national unemployment rate is greater than 7 percent at the time of the election, presidential incumbents are not reelected.”

Collecting data

In the research model designed to test this hypothesis, the dependent variable (the phenomenon that is affected by other variables) would be the reelection of incumbent presidents; the independent variable (the phenomenon that may have some effect on the dependent variable) would be the national unemployment rate. You could test the relationship between the independent and dependent variables by collecting data on unemployment rates and the reelection of incumbent presidents and comparing the two sets of information. If you found that in every instance that the national unemployment rate was greater than 7 percent at the time of a presidential election the incumbent lost, you would have significant support for our hypothesis.

However, research in political science seldom yields immediately conclusive results. In this case, for example, although in most recent presidential elections our hypothesis holds true, President Franklin Roosevelt was reelected in 1936 despite the fact that the national unemployment rate was 17%. To explain this important exception and to make certain that other factors besides high unemployment rates were not primarily responsible for the defeat of incumbent presidents in other election years, you would need to do further research. So you can see how political scientists use the scientific method to build ever more precise and persuasive theories and how you might begin to think about the topics that interest you as you write your paper.

Clear, consistent, objective writing

Since political scientists construct and assess theories in accordance with the principles of the scientific method, writing in the field conveys the rigor, objectivity, and logical consistency that characterize this method. Thus political scientists avoid the use of impressionistic or metaphorical language, or language which appeals primarily to our senses, emotions, or moral beliefs. In other words, rather than persuade you with the elegance of their prose or the moral virtue of their beliefs, political scientists persuade through their command of the facts and their ability to relate those facts to theories that can withstand the test of empirical investigation. In writing of this sort, clarity and concision are at a premium. To achieve such clarity and concision, political scientists precisely define any terms or concepts that are important to the arguments that they make. This precision often requires that they “operationalize” key terms or concepts. “Operationalizing” simply means that important—but possibly vague or abstract—concepts like “justice” are defined in ways that allow them to be measured or tested through scientific investigation.

Fortunately, you will generally not be expected to devise or operationalize key concepts entirely on your own. In most cases, your professor or the authors of assigned readings will already have defined and/or operationalized concepts that are important to your research. And in the event that someone hasn’t already come up with precisely the definition you need, other political scientists will in all likelihood have written enough on the topic that you’re investigating to give you some clear guidance on how to proceed. For this reason, it is always a good idea to explore what research has already been done on your topic before you begin to construct your own argument. See our handout on making an academic argument .

Example of an operationalized term

To give you an example of the kind of rigor and objectivity political scientists aim for in their writing, let’s examine how someone might operationalize a term. Reading through this example should clarify the level of analysis and precision that you will be expected to employ in your writing. Here’s how you might define key concepts in a way that allows us to measure them.

We are all familiar with the term “democracy.” If you were asked to define this term, you might make a statement like the following:

“Democracy is government by the people.”

You would, of course, be correct—democracy is government by the people. But, in order to evaluate whether or not a particular government is fully democratic or is more or less democratic when compared with other governments, we would need to have more precise criteria with which to measure or assess democracy. For example, here are some criteria that political scientists have suggested are indicators of democracy:

- Freedom to form and join organizations

- Freedom of expression

- Right to vote

- Eligibility for public office

- Right of political leaders to compete for support

- Right of political leaders to compete for votes

- Alternative sources of information

- Free and fair elections

- Institutions for making government policies depend on votes and other expressions of preference

If we adopt these nine criteria, we now have a definition that will allow us to measure democracy empirically. Thus, if you want to determine whether Brazil is more democratic than Sweden, you can evaluate each country in terms of the degree to which it fulfills the above criteria.

What counts as good writing in political science?

While rigor, clarity, and concision will be valued in any piece of writing in political science, knowing the kind of writing task you’ve been assigned will help you to write a good paper. Two of the most common kinds of writing assignments in political science are the research paper and the theory paper.

Writing political science research papers

Your instructors use research paper assignments as a means of assessing your ability to understand a complex problem in the field, to develop a perspective on this problem, and to make a persuasive argument in favor of your perspective. In order for you to successfully meet this challenge, your research paper should include the following components:

- An introduction

- A problem statement

- A discussion of methodology

- A literature review

- A description and evaluation of your research findings

- A summary of your findings

Here’s a brief description of each component.

In the introduction of your research paper, you need to give the reader some basic background information on your topic that suggests why the question you are investigating is interesting and important. You will also need to provide the reader with a statement of the research problem you are attempting to address and a basic outline of your paper as a whole. The problem statement presents not only the general research problem you will address but also the hypotheses that you will consider. In the methodology section, you will explain to the reader the research methods you used to investigate your research topic and to test the hypotheses that you have formulated. For example, did you conduct interviews, use statistical analysis, rely upon previous research studies, or some combination of all of these methodological approaches?

Before you can develop each of the above components of your research paper, you will need to conduct a literature review. A literature review involves reading and analyzing what other researchers have written on your topic before going on to do research of your own. There are some very pragmatic reasons for doing this work. First, as insightful as your ideas may be, someone else may have had similar ideas and have already done research to test them. By reading what they have written on your topic, you can ensure that you don’t repeat, but rather learn from, work that has already been done. Second, to demonstrate the soundness of your hypotheses and methodology, you will need to indicate how you have borrowed from and/or improved upon the ideas of others.

By referring to what other researchers have found on your topic, you will have established a frame of reference that enables the reader to understand the full significance of your research results. Thus, once you have conducted your literature review, you will be in a position to present your research findings. In presenting these findings, you will need to refer back to your original hypotheses and explain the manner and degree to which your results fit with what you anticipated you would find. If you see strong support for your argument or perhaps some unexpected results that your original hypotheses cannot account for, this section is the place to convey such important information to your reader. This is also the place to suggest further lines of research that will help refine, clarify inconsistencies with, or provide additional support for your hypotheses. Finally, in the summary section of your paper, reiterate the significance of your research and your research findings and speculate upon the path that future research efforts should take.

Writing in political theory

Political theory differs from other subfields in political science in that it deals primarily with historical and normative, rather than empirical, analysis. In other words, political theorists are less concerned with the scientific measurement of political phenomena than with understanding how important political ideas develop over time. And they are less concerned with evaluating how things are than in debating how they should be. A return to our democracy example will make these distinctions clearer and give you some clues about how to write well in political theory.

Earlier, we talked about how to define democracy empirically so that it can be measured and tested in accordance with scientific principles. Political theorists also define democracy, but they use a different standard of measurement. Their definitions of democracy reflect their interest in political ideals—for example, liberty, equality, and citizenship—rather than scientific measurement. So, when writing about democracy from the perspective of a political theorist, you may be asked to make an argument about the proper way to define citizenship in a democratic society. Should citizens of a democratic society be expected to engage in decision-making and administration of government, or should they be satisfied with casting votes every couple of years?

In order to substantiate your position on such questions, you will need to pay special attention to two interrelated components of your writing: (1) the logical consistency of your ideas and (2) the manner in which you use the arguments of other theorists to support your own. First, you need to make sure that your conclusion and all points leading up to it follow from your original premises or assumptions. If, for example, you argue that democracy is a system of government through which citizens develop their full capacities as human beings, then your notion of citizenship will somehow need to support this broad definition of democracy. A narrow view of citizenship based exclusively or primarily on voting probably will not do. Whatever you argue, however, you will need to be sure to demonstrate in your analysis that you have considered the arguments of other theorists who have written about these issues. In some cases, their arguments will provide support for your own; in others, they will raise criticisms and concerns that you will need to address if you are going to make a convincing case for your point of view.

Drafting your paper

If you have used material from outside sources in your paper, be sure to cite them appropriately in your paper. In political science, writers most often use the APA or Turabian (a version of the Chicago Manual of Style) style guides when formatting references. Check with your instructor if they have not specified a citation style in the assignment. For more information on constructing citations, see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial.

Although all assignments are different, the preceding outlines provide a clear and simple guide that should help you in writing papers in any sub-field of political science. If you find that you need more assistance than this short guide provides, refer to the list of additional resources below or make an appointment to see a tutor at the Writing Center.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Becker, Howard S. 2007. Writing for Social Scientists: How to Start and Finish Your Thesis, Book, or Article , 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cuba, Lee. 2002. A Short Guide to Writing About Social Science , 4th ed. New York: Longman.

Lasswell, Harold Dwight. 1936. Politics: Who Gets What, When, How . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Scott, Gregory M., and Stephen M. Garrison. 1998. The Political Science Student Writer’s Manual , 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Turabian, Kate. 2018. A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, Dissertations , 9th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.5: Research Paper Project Management

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 76257

- Josue Franco

- Cuyamaca College

Learning Goals

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Remember the process of writing a research paper plan

- Create a research paper plan

A goal of an Introduction to Political Science Research Methods course is to prepare you to write a well-developed research paper that you could reasonably consider submitting to a journal for peer review. This may sound ambitious, since writing a publication-quality research paper is typically reserved for faculty who already hold a doctoral degree or advanced graduate students. However, the idea that a first or second-year student is not capable is a tradition in need of change. Students, especially those enrolled at community colleges, have a wealth of lived experiences and unique perspectives that, in many ways, are not permeating throughout the current ranks of graduate students and faculty.

Writing a research paper should be viewed like managing a project that consists of workflows. Workflows serve as a template for how you can take a large project (such as writing a Research Paper) and disaggregate it into specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and timely tasks. This is called “project management” because you are taking a “big” project, organizing it into “smaller” projects, sequencing the smaller projects, completing the smaller projects, and then bringing all the smaller projects together to demonstrate completion of the “big” project. In the real-world, this is a valuable ability and skill to have.

We have all project managed; we just never call it that. For example, have you had a plan a birthday party? Or maybe organize a family dinner? Or maybe write a research paper in high school? The party, dinner, and researcher paper are all examples of projects. And you managed these projects from beginning to end. The result of your efforts was a “great time” or “delicious dinner” or “excellent work”. In other words, don’t underestimate your ability to successfully manage a complex project.

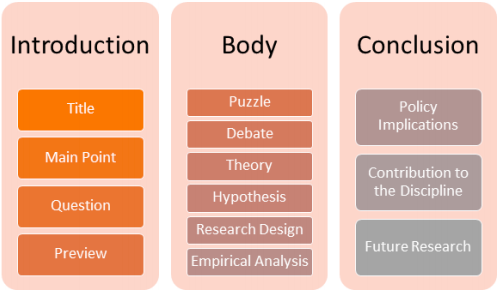

The process of writing a political science research paper closely follows the process of analyzing a journal article. A research paper consists of an introduction, body, and conclusion. The introduction contains the title, the main point, question, and preview of the body. The body includes the puzzle, debate, theory, hypothesis, research design, and empirical analysis. Finally, the conclusion contains policy implications, contribution to the discipline, and future research.

\(\PageIndex{1}\): Visualization of research paper parts

A crucial difference between analyzing a journal article and writing a research paper is a literature review. When analyzing a journal article, you don’t search for a literature review. Rather, you look for the outputs of a literature review process: puzzle, debate, and theory. A literature review is your reading and analysis of anywhere from 10 to 100 journal articles and books related to your research paper topic. This sounds like a lot, and it is. But don’t be exasperated by the number of articles or books you must read, simply recognize that you need to absorb existing knowledge to contribute new knowledge.

A literature review can serve as an obstacle for the first-time writer of a political science research paper. The reason that such an obstacle is just the sheer amount of reading that one needs to engage in in order to understand a topic. Now, we may have difficulty in reading because we have a learning disability or deficit disorder. Or, reading can be challenging because we don’t have access to the articles and books that help make up our understanding of a topic. The key is not to get caught up in what we cannot do what we have trouble doing, but rather to focus on what we can accomplish.

How can we conduct a literature review? First, we want to select a topic that we are interested in. Now there’s a range of things in the world that we can explore. And because the world is complicated, there is a lot that we can explore. But some straightforward advice is to research something you care about. What is something from your personal experiences, or what you observed in your family and community, or what you think society is grappling with, that you care about? The answer to this question is what you should research.

After we selected a topic, we should search for more information by visiting our library, talking with a librarian, meeting with our professor, and visiting reputable information sources online.

The campus library serves as a repository of information and knowledge. Librarians are trained professionals who understand the science of information: what it is, how it’s organized, and how we give it meaning. So, you can meet with the librarian and ask for their help to navigate in person and online resources related to your topic. What a librarian may ask you, in addition to your topic, is what your research question?

You may be asking what’s the difference between a question and a research question? Frankly, one question has the adjective “research” in front of it. A question generally with the word: who, what, when, where, why, and how. On the other hand, a research question typically starts with why. A why question suggest that there are two things, also known as variables, that interact in a way that is perplexing and intriguing to you. For example, why do some politicians tweet profusely, and other politicians don’t even have a Twitter account? A secondary question is: what causes a politician to utilize social media? Now the answers to these questions require some research that something that you can do.

With your topic and research question in hand, you will be directed to books, journal articles, and current event publications to learn more about your topic. Sifting through the mountains of information that exist today is a skill. Honing this skill is a lifelong process because the information environment is constantly changing. For your purposes in writing a research paper, you should consult with your professor about what are reputable books, journals, and new sources. In political science, university presses, the journals of national and regional associations, and major news outlets all serve as reputable sources.

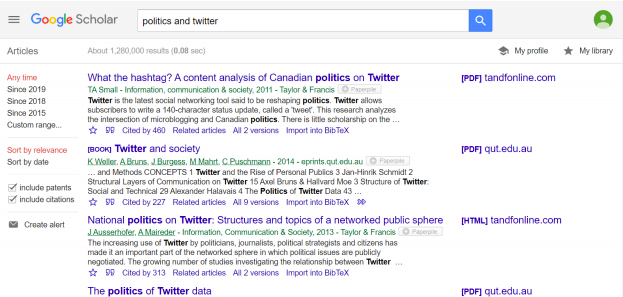

A go-to source for finding academic articles and books on a topic is Google Scholar. Unlike Google search engine, which provides results from all over the World Wide Web, Google Scholar is a search engine that limits results to academic articles and books. By narrowing the results that are provided, Google scholar helps you cut through the noise that exist on the Internet. For example, in my web browser I type in https://scholar.google.com/ . In the search box, I type “politics and twitter” and below the following results appear:

\(\PageIndex{2}\): Output of Google Scholar search of “politics and twitter”

In this example, we see that there are over 1.2 million results. How do you decide on the 10, 20, or 100 articles and books to read? One way to shorten your reading list is to see how many times something has been cited. In the example above, we see that the article titled “What the hashtag?” has been cited 460 times. If an article or book is cited in the hundreds, or thousands, of times, then you should at its your reading list because it means that a lot of people are focused on the topic, or the findings, or the argument that that object represents.

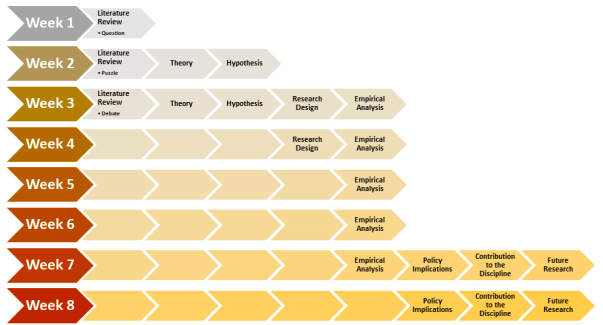

Writing a political science research paper is a generally nonlinear process. This means that you can go from conducting a Literature Review, and jump to Policy Implications, and then update your Empirical Analysis to account for some new information you read. Thus, the suggestion below is not meant to be “the” process, but rather one of many creative processes that adapt to your way of thinking, working, and being successful. However, while recognizing your creativity, it is important to give order to the process. When you are taking a 10-week or 16- week long course, you need to take a big project and break it up into smaller projects. Below is an example of how you segment a research paper into its constituent parts over an 8-week period.

\(\PageIndex{3}\): Proposed 8-week timeline for preparing your research paper

POLSC101: Introduction to Political Science

Research in political science.

This handout is designed to teach you how to conduct original political science research. While you won't be asked to write a research paper, this handout provides important information on the "scientific" approach used by political scientists. Pay particularly close attention to the section that answers the question "what is scientific about political science?"

If you were going to conduct research in biology or chemistry, what would you do? You would probably create a hypothesis, and then design an experiment to test your hypothesis. Based on the results of your experiment, you would draw conclusions. Political scientists follow similar procedures. Like a scientist who researches biology or chemistry, political scientists rely on objectivity, data, and procedure to draw conclusions. This article explains the process of operationalizing variables. Why is that an important step in social science research?

Defining politics and political science

Political scientist Harold Laswell said it best: at its most basic level, politics is the struggle of "who gets what, when, how". This struggle may be as modest as competing interest groups fighting over control of a small municipal budget or as overwhelming as a military stand-off between international superpowers. Political scientists study such struggles, both small and large, in an effort to develop general principles or theories about the way the world of politics works. Think about the title of your course or re-read the course description in your syllabus. You'll find that your course covers a particular sector of the large world of "politics" and brings with it a set of topics, issues, and approaches to information that may be helpful to consider as you begin a writing assignment. The diverse structure of political science reflects the diverse kinds of problems the discipline attempts to analyze and explain. In fact, political science includes at least eight major sub-fields:

- American politics examines political behavior and institutions in the United States.

- Comparative politics analyzes and compares political systems within and across different geographic regions.

- International relations investigates relations among nation-states and the activities of international organizations such as the United Nations, the World Bank, and NATO, as well as international actors such as terrorists, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and multi-national corporations (MNCs).

- Political theory analyzes fundamental political concepts such as power and democracy and foundational questions, like "How should the individual and the state relate?"

- Political methodology deals with the ways that political scientists ask and investigate questions.

- Public policy examines the process by which governments make public decisions.

- Public administration studies the ways that government policies are implemented.

- Public law focuses on the role of law and courts in the political process.

What is scientific about political science?

Investigating relationships

Although political scientists are prone to debate and disagreement, the majority view the discipline as a genuine science. As a result, political scientists generally strive to emulate the objectivity as well as the conceptual and methodological rigor typically associated with the so-called "hard" sciences (e.g., biology, chemistry, and physics). They see themselves as engaged in revealing the relationships underlying political events and conditions. Based on these revelations, they attempt to state general principles about the way the world of politics works. Given these aims, it is important for political scientists' writing to be conceptually precise, free from bias, and well-substantiated by empirical evidence. Knowing that political scientists value objectivity may help you in making decisions about how to write your paper and what to put in it.

Political theory is an important exception to this empirical approach. You can learn more about writing for political theory classes in the section "Writing in Political Theory" below.

Building theories

Since theory-building serves as the cornerstone of the discipline, it may be useful to see how it works. You may be wrestling with theories or proposing your own as you write your paper. Consider how political scientists have arrived at the theories you are reading and discussing in your course. Most political scientists adhere to a simple model of scientific inquiry when building theories. The key to building precise and persuasive theories is to develop and test hypotheses. Hypotheses are statements that researchers construct for the purpose of testing whether or not a certain relationship exists between two phenomena. To see how political scientists use hypotheses, and to imagine how you might use a hypothesis to develop a thesis for your paper, consider the following example. Suppose that we want to know whether presidential elections are affected by economic conditions. We could formulate this question into the following hypothesis: "When the national unemployment rate is greater than 7 percent at the time of the election, presidential incumbents are not reelected".

Collecting data

In the research model designed to test this hypothesis, the dependent variable (the phenomenon that is affected by other variables) would be the reelection of incumbent presidents; the independent variable (the phenomenon that may have some effect on the dependent variable) would be the national unemployment rate. You could test the relationship between the independent and dependent variables by collecting data on unemployment rates and the reelection of incumbent presidents and comparing the two sets of information. If you found that in every instance that the national unemployment rate was greater than 7 percent at the time of a presidential election the incumbent lost, you would have significant support for our hypothesis.

However, research in political science seldom yields immediately conclusive results. In this case, for example, although in most recent presidential elections our hypothesis holds true, President Franklin Roosevelt was reelected in 1936 despite the fact that the national unemployment rate was 17%. To explain this important exception and to make certain that other factors besides high unemployment rates were not primarily responsible for the defeat of incumbent presidents in other election years, you would need to do further research. So you can see how political scientists use the scientific method to build ever more precise and persuasive theories and how you might begin to think about the topics that interest you as you write your paper.

Clear, consistent, objective writing

Since political scientists construct and assess theories in accordance with the principles of the scientific method, writing in the field conveys the rigor, objectivity, and logical consistency that characterize this method. Thus political scientists avoid the use of impressionistic or metaphorical language, or language which appeals primarily to our senses, emotions, or moral beliefs. In other words, rather than persuade you with the elegance of their prose or the moral virtue of their beliefs, political scientists persuade through their command of the facts and their ability to relate those facts to theories that can withstand the test of empirical investigation. In writing of this sort, clarity and concision are at a premium. To achieve such clarity and concision, political scientists precisely define any terms or concepts that are important to the arguments that they make. This precision often requires that they "operationalize" key terms or concepts. "Operationalizing" simply means that important – but possibly vague or abstract – concepts like "justice" are defined in ways that allow them to be measured or tested through scientific investigation.

Fortunately, you will generally not be expected to devise or operationalize key concepts entirely on your own. In most cases, your professor or the authors of assigned readings will already have defined and/or operationalized concepts that are important to your research. And in the event that someone hasn't already come up with precisely the definition you need, other political scientists will in all likelihood have written enough on the topic that you're investigating to give you some clear guidance on how to proceed. For this reason, it is always a good idea to explore what research has already been done on your topic before you begin to construct your own argument. (See our handout on making an academic argument.)

Example of an operationalized term

To give you an example of the kind of "rigor" and "objectivity" political scientists aim for in their writing, let's examine how someone might operationalize a term. Reading through this example should clarify the level of analysis and precision that you will be expected to employ in your writing. Here's how you might define key concepts in a way that allows us to measure them.

We are all familiar with the term "democracy". If you were asked to define this term, you might make a statement like the following: "Democracy is government by the people". You would, of course, be correct – democracy is government by the people. But, in order to evaluate whether or not a particular government is fully democratic or is more or less democratic when compared with other governments, we would need to have more precise criteria with which to measure or assess democracy. Most political scientists agree that these criteria should include the following rights and freedoms for citizens:

- Freedom to form and join organizations

- Freedom of expression

- Right to vote

- Eligibility for public office

- Right of political leaders to compete for support

- Right of political leaders to compete for votes

- Alternative sources of information

- Free and fair elections

- Institutions for making government policies depend on votes and other expressions of preference

By adopting these nine criteria, we now have a definition that will allow us to measure democracy. Thus, if you want to determine whether Brazil is more democratic than Sweden, you can evaluate each country in terms of the degree to which it fulfills the above criteria.

What counts as good writing in political science?

While rigor, clarity, and concision will be valued in any piece of writing in political science, knowing the kind of writing task you've been assigned will help you to write a good paper. Two of the most common kinds of writing assignments in political science are the research paper and the theory paper.

Writing political science research papers

Your instructors use research paper assignments as a means of assessing your ability to understand a complex problem in the field, to develop a perspective on this problem, and to make a persuasive argument in favor of your perspective. In order for you to successfully meet this challenge, your research paper should include the following components: (1) an introduction, (2) a problem statement, (3) a discussion of methodology, (4) a literature review, (5) a description and evaluation of your research findings, and (6) a summary of your findings. Here's a brief description of each component.

In the introduction of your research paper, you need to give the reader some basic background information on your topic that suggests why the question you are investigating is interesting and important. You will also need to provide the reader with a statement of the research problem you are attempting to address and a basic outline of your paper as a whole. The problem statement presents not only the general research problem you will address but also the hypotheses that you will consider. In the methodology section, you will explain to the reader the research methods you used to investigate your research topic and to test the hypotheses that you have formulated. For example, did you conduct interviews, use statistical analysis, rely upon previous research studies, or some combination of all of these methodological approaches?

Before you can develop each of the above components of your research paper, you will need to conduct a literature review. A literature review involves reading and analyzing what other researchers have written on your topic before going on to do research of your own. There are some very pragmatic reasons for doing this work. First, as insightful as your ideas may be, someone else may have had similar ideas and have already done research to test them. By reading what they have written on your topic, you can ensure that you don't repeat, but rather learn from, work that has already been done. Second, to demonstrate the soundness of your hypotheses and methodology, you will need to indicate how you have borrowed from and/or improved upon the ideas of others.

By referring to what other researchers have found on your topic, you will have established a frame of reference that enables the reader to understand the full significance of your research results. Thus, once you have conducted your literature review, you will be in a position to present your research findings. In presenting these findings, you will need to refer back to your original hypotheses and explain the manner and degree to which your results fit with what you anticipated you would find. If you see strong support for your argument or perhaps some unexpected results that your original hypotheses cannot account for, this section is the place to convey such important information to your reader. This is also the place to suggest further lines of research that will help refine, clarify inconsistencies with, or provide additional support for your hypotheses. Finally, in the summary section of your paper, reiterate the significance of your research and your research findings and speculate upon the path that future research efforts should take.

Writing in political theory

Political theory differs from other subfields in political science in that it deals primarily with historical and normative, rather than empirical, analysis. In other words, political theorists are less concerned with the scientific measurement of political phenomena than with understanding how important political ideas develop over time. And they are less concerned with evaluating how things are than in debating how they should be. A return to our democracy example will make these distinctions clearer and give you some clues about how to write well in political theory.

Earlier, we talked about how to define democracy empirically so that it can be measured and tested in accordance with scientific principles. Political theorists also define democracy, but they use a different standard of measurement. Their definitions of democracy reflect their interest in political ideals – for example, liberty, equality, and citizenship – rather than scientific measurement. So, when writing about democracy from the perspective of a political theorist, you may be asked to make an argument about the proper way to define citizenship in a democratic society. Should citizens of a democratic society be expected to engage in decision-making and administration of government, or should they be satisfied with casting votes every couple of years?

In order to substantiate your position on such questions, you will need to pay special attention to two interrelated components of your writing: (1) the logical consistency of your ideas and (2) the manner in which you use the arguments of other theorists to support your own. First, you need to make sure that your conclusion and all points leading up to it follow from your original premises or assumptions. If, for example, you argue that democracy is a system of government through which citizens develop their full capacities as human beings, then your notion of citizenship will somehow need to support this broad definition of democracy. A narrow view of citizenship based exclusively or primarily on voting probably will not do. Whatever you argue, however, you will need to be sure to demonstrate in your analysis that you have considered the arguments of other theorists who have written about these issues. In some cases, their arguments will provide support for your own; in others, they will raise criticisms and concerns that you will need to address if you are going to make a convincing case for your point of view.

Drafting your paper

If you have used material from outside sources in your paper, be sure to cite them appropriately in your paper. In political science, writers most often use the APA or Turabian (a version of the Chicago Manual of Style) style guides when formatting references. Check with your instructor if he or she has not specified a citation style in the assignment. For more information on constructing citations, see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial.

Although all assignments are different, the preceding outlines provide a clear and simple guide that should help you in writing papers in any sub-field of political science. If you find that you need more assistance than this short guide provides, refer to the list of additional resources below or make an appointment to see a tutor at the Writing Center.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing the original version of this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout's topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find the latest publications on this topic. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial.

Becker, Howard S. 1986. Writing for Social Scientists: How to Start and Finish Your Thesis, Book, or Article . Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Cuba, Lee. 2002. A Short Guide to Writing about Social Science , Fourth Edition. New York: Longman.

Lasswell, Harold Dwight. 1936. Politics: Who Gets What, When, How . New York, London: Whittlesey House, McGraw-Hill Book Company, inc.

Scott, Gregory M. and Stephen M. Garrison. 1998. The Political Science Student Writer's Manual , Second Edition. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, Inc.

Turabian, Kate L. 1996. A Manual for Writers of Term Papers , Theses, and Dissertations, Sixth Edition. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

University Libraries

Psci 3300: introduction to political research.

- Library Accounts

- Selecting a Topic for Research

- From Topic to Research Question

- From Question to Theories, Hypotheses, and Research Design

- Annotated Bibliographies

- The Literature Review

- Search Strategies for Ann. Bibliographies & Lit. Reviews

- Find PSCI Books for Ann. Bibliographies & Lit. Reviews

- Databases & Electronic Resources for Your Lit. Review

- Methods, Data Analysis, Results, Limitations, and Conclusion

- Finding Data and Statistics for the Data Analysis

- Citing Sources for the Reference Page

Need Help with Basic and Advance Research?

Visit the Basic and Advanced Library Research Guide to learn more about the library.

If you select "no," please send me an email so I can improve this guide.

Introduction to Political Research

This class page is for the quantitative methods research paper in the PSCI 3300 course (Introduction to Political Research); however, it has basic research steps and tools that are useful for any quantitative research you do. By the end of this class, you have completed a quantitative methods research paper, and each page of this guide is designed to help walk you through this type of research design.

If you find you need more help, use the Ask Us services. Library reference staff members can be reached in person and through phone and email. You may also contact the Subject Librarian for the Political Science Department, Brea Henson .

What is on Course Reserve for this Class?

Check with your professor to make sure this is the book that they will be using for your class.

Where to Find your Course Reserves

Your text books are located at the Sycamore Library Services Desk on two hour reserve (you will need your UNT ID card).

Finding Course Reserves

- Visit the Course Reserves page to search by course letter or your instructor's last name.

- Option 1: Search PSCI 2300 in the SEARCH BY COURSE CODE search box.

- Option 2: Search your professor's name by using the SEARCH BY INSTRUCTOR NAME (LAST, FIRST) search box.

- Take the call number and your UNT ID card to the Sycamore Library Services Desk to request the book.

Alternative Text: Sage Research Methods Online

Statistics for Political Analysis will be an introduction to stats geared to political science students. Marchant-Shapiro will focus on the statistical tools most often used by political scientists and will use political examples, cases, and data throughout to show students how to answer real questions about politics using real political data. Her goal is to provide clear and accessible explanation and instruction so students not only understand the math, but can do the math. But instead of focusing on equations, Marchant-Shapiro will take a “how to” approach to doing the math, making the book much more approachable to political science students. Each chapter follows a 4-part structure: 1) the concept will be introduced with a real world example; 2) the statistical measure will be calculated using math; 3) the statistical concept will be used to solve a real-world problem using a political example, and 4) the student will use the concept to solve another real-world problem. Her exercises include those requiring hand-calculations and those requiring a statistical package like SPSS, and ask students to produce memos to emphasize how marketable and applicable their new skills are to a broad array of careers and jobs. This book is online and available through the Sage Research Methods Online Database.

General Library Information

- UNT Libraries Home Page

- Sycamore Library phone 940) 565-2194

- Sycamore Library Hours

- 24 hour study space in Willis Library

UNT Libraries Locations

UNT has several libraries. Most Political Science materials can be found on the Mezzanine Level of Sycamore Library, which is located inside Sycamore Hall You can find a map of library locations here:

- Campus Map (click on the "Sycamore Hall" link)

- Library Locations

The UNT Libraries offer a variety of service for our students:

- Students can borrow or renew books at our Library Services Desks with a current student ID.

- Photocopying, scanning, and printing are available at all libraries ( 24/7 at our Willis Library ).

- Other library technology includes interactive whiteboards and instruction rooms with screens and projectors available in our Collaboration and Learning Commons in the Sycamore Library as well as gaming stations at our Media Library .

- The Libraries offer several study areas for both quiet and group study!

- Next: Library Accounts >>

Copyright © University of North Texas. Some rights reserved. Except where otherwise indicated, the content of this library guide is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) license . Suggested citation for citing this guide when adapting it:

This work is a derivative of "PSCI 3300: Introduction to Political Research" , created by [author name if apparent] and © University of North Texas, used under CC BY-NC 4.0 International .

- Last Updated: Nov 13, 2023 4:28 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.unt.edu/PSCI3300

Additional Links

UNT: Apply now UNT: Schedule a tour UNT: Get more info about the University of North Texas

UNT: Disclaimer | UNT: AA/EOE/ADA | UNT: Privacy | UNT: Electronic Accessibility | UNT: Required Links | UNT: UNT Home

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Introduction to Political Science

Related Papers

Charles M Kasongo

Pablo Escobar

ALFREDO MANZANO AMEZQUITA

This third edition of the best-selling The Fundamentals of Political Science Research provides an introduction to the scientific study of politics. It offers the basic tools necessary for readers to become both critical consumers and beginning producers of scientific research on politics. The authors present an integrated approach to research design and empirical analyses whereby researchers can develop and test causal theories. The authors use examples from political science research that students will find interesting and inspiring, and that will help them understand key concepts. The book makes technical material accessible to students who might otherwise be intimidated by mathematical examples. This revised third edition features new "Your Turn" boxes meant to engage students. The edition also has new sections added throughout the book to enhance the content's clarity and breadth of coverage.

Jean-Thomas Martelli

Tutorial aims This conference aims first of all at helping students gain a comprehensive understanding of the main themes presented in the lecture and the assigned readings, thus contributing to their grasp of the fundamentals of Political Science. Second, the conference intends to provide students with both the methodological and conceptual tools necessary to successfully complete different types of oral and written assignments. Finally, the conference contains an important interactive dimension and will strongly encourage students to participate in class discussions. The course is divided into two large sections. The first section – " Systems and regimes " – will focus on the structural and institutional characteristics of politics and political competition. The second – " Actors and institutions " – will take a bottom-up approach to politics and show how it interacts with the structural features discussed in section one. Preparation For each conference, students are expected to have read all assigned readings and to have studied the content of the previous lectures and tutorials. Students are expected to study the literature carefully and prepare it in a critical and analytical way. There are lectures by the instructor, student presentations focusing on a critique of the articles, as well as general class discussion about the main issues. The lecturer will coordinate and lead the discussions together with the students that are assigned to give a presentation or participate in a debate. The students that are not directly involved in the presentation should demonstrate that they have prepared for the class by formulating two or three questions or critical reflections on the readings and presentations, based on their interests and knowledge as well as current events reported in the media. The core idea of the course is student participation.

Mary Fasipe

Armando Marques-Guedes

An annotated bibliography submitted for the research based argument. At least twelve sources are annotated with a brief summary of the sources' research and content. A brief thesis statement is provided to underline the necessity of each source.

polmeth.wustl.edu

Tracy Lightcap

Copyright: The authors Disclaimer: IES Proceedings cannot be held responsible for the errors or any consequences arising from the use of information contained in this journal. The views and the opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the publisher and editors

Charles Stewart

Introduces students to the conduct of political research using quantitative methodologies. The methods are examined in the context of specific political research activities like public opinion surveys, voting behavior, Congressional behavior, comparisons of political processes in different countries, and the evaluation of public policies. Students participate in joint class projects and conduct individual projects. Does not count toward HASS Requirement.

RELATED PAPERS

IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I-regular Papers

Brian Munsky

Reflections on the Foundations of Mathematics

Journal of religion and health

Masoumeh Bagheri- Nesami

Michaela Endres

fausto cardosomartinez

Çocuk ve Medeniyet Dergisi

Şafak Bilen

Journal of Applied Phycology

Maria Rovilla Luhan

European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery

Steinarr Björnsson

Janete Da Silva

Lecture Notes in Computer Science

Huiping Cao

Frontiers in Oncology

Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Jens Vogel-claussen

La salvaguardia delle opere d'arte lombarde a Sondalo in Valtellina: 1943-1945

Cecilia Ghibaudi

Tatjana Atanasova-Pacemska

Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado

Journal Plus Education

Diana Redes

Epistēmēs Metron Logos

Demetrios Lekkas

European journal of public health

Regina Amado

International Journal of Education

Sunnie Lee Watson

Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology

Jim Riviere

Migration, Cross-Border Trade and Development in Africa

Inocent Moyo

hukyytj jkthjfgr

Physical Review E

Parongama Sen

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Introduction to Political Science Research

Course Details

This course serves as an introduction to the philosophy and practice of political science including basic research methods in political science. We will explore what is meant by “science” and the scientific method, and the various subfields of political science. We will also cover the various stages of the research process, as well as the basics of political analysis. By the end of the course, students should develop:

- a knowledge and understanding of basic concepts in political science research;

- the ability to offer sophisticated, critical analyses of empirical work;

- competence in rudimentary statistical skills;

- the skills to write quality review and research papers in upper division courses.

Introduction to Political Science

(3 reviews)

Mark Carl Rom, Georgetown University

Masaki Hidaka, American University

Rachel Bzostek Walker, Collin College

Copyright Year: 2022

Publisher: OpenStax

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Michelle Payne, Associate Professor, Political Science, Texas Wesleyan University on 2/29/24

Selected key terms are both relevant and clearly defined read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

Selected key terms are both relevant and clearly defined

Content Accuracy rating: 5

The book is packed with both cumulative, foundational knowledge and associated current event references, and as far as I have read, both reflect superior accuracy

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

The book is packed with both cumulative, foundational knowledge and associated current event references, which tie together theory, concept, and relevancy is an easy to understand format.

Clarity rating: 5

Form an Instructor viewpoint, very clearly written- particularly the review questions. The text to video connections are also concisely and clearly stated.

Consistency rating: 5

This is one of the reasons I would like to use the text- the terminology, structure and general outlay of the material are logically connected and lend to a smooth integration and adaptation.

Modularity rating: 5

I set out a tentative outline for moving context around, and had no transitional issues- I also tentatively integrated my material into the mix and it reads well, with no loss of integrity to the material.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

Very straightforward- easy to adapt if need to.

Interface rating: 5

Didn't see any issues- I will say that the links to government websites were placed discreetly yet noticeably in the text and I see that ease of accessibility as an added bonus for students

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

I haven't found any

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

The diverse pictures, stories, illustrations and video links cover this aspect well.

I am excited to find a text that is so packed with info, yet approachable for students, even in a dual enrollment course.

Reviewed by Larry Carter, Distinguished Senior Lecturere, University of Texas at Arlington on 4/4/23

Covers all areas needed for American intro course. read more

Covers all areas needed for American intro course.

Content is accurate and unbiased.

Should hold up well.

Good clarity.

Layout and content consistent

Easily and readily divisible.

Good flow. Layout good.

Free of interface questions.

No grammatical errors

Not culturally insensitive

Good layout and content.

Reviewed by Katrina Heimark, Lecturer, Century College on 3/7/23

Introduction to Political Science covers all the major topics and has a global focus, using examples from around the world. My only observation on content that was not covered in-depth was regarding regime change and the factors that cause... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

Introduction to Political Science covers all the major topics and has a global focus, using examples from around the world. My only observation on content that was not covered in-depth was regarding regime change and the factors that cause democracies to fail or authoritarian regimes to rise. This is an important part of the comparative political science literature that could have been focused on in more detail.

I have found the content to be accurate, unbiased, and with citation of sources.

Students are so impressed with the real-world examples of this text book, and the fact that it was published in 2022 makes it a great resources for them. The content is relevant today, but should also be relevant for the next 5-10 years. Updates/more relevant examples should be easy to find once this text is a bit older.

This is a great intro text for any student who has no experience or exposure to political science. It is straightforward and complex terms are explained in such a way that it is easy for all audiences to understand.

I have found this text to be consistent in terms of its organization, terminology, and framework.

The online version of this text is fantastic in terms of the layout and accessibility of the different content modules. The modules are broken up in a way that makes sense, is logical, and also can stand alone.

The book has a great mix of video, text, and images and is clearly organized both within chapters, sub-chapters, and as a textbook as a whole.

The interface is easy to use, particularly the online textbook. Allows for highlighting in different colors and also creation of notes.

No grammatical errors.

This book has excellent examples from across different country and cultural contexts. While designed for a US audience, the textbook does a fantastic job of using examples from different regions, cultures, and countries to illustrate the different political examples. One region is not overly represented, nor is one region used exclusively for negative examples. I found this book to be incredibly fair, accurate, and presenting an amazing culturally diverse content across subject areas.

This book has been great for an introductory political science course that I have taught to first year college students. I find it to be at the perfect level for these students--clear, relevant, and also challenges them to see the world through multiple perspectives.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- 1.1 Defining Politics: Who Gets What, When, Where, How, and Why?

- 1.2 Public Policy, Public Interest, and Power

- 1.3 Political Science: The Systematic Study of Politics

- 1.4 Normative Political Science

- 1.5 Empirical Political Science

- 1.6 Individuals, Groups, Institutions, and International Relations

- Review Questions

- Suggested Readings

- 2.1 What Goals Should We Seek in Politics?

- 2.2 Why Do Humans Make the Political Choices That They Do?

- 2.3 Human Behavior Is Partially Predictable

- 2.4 The Importance of Context for Political Decisions

- 3.1 The Classical Origins of Western Political Ideologies

- 3.2 The Laws of Nature and the Social Contract

- 3.3 The Development of Varieties of Liberalism

- 3.4 Nationalism, Communism, Fascism, and Authoritarianism

- 3.5 Contemporary Democratic Liberalism

- 3.6 Contemporary Ideologies Further to the Political Left

- 3.7 Contemporary Ideologies Further to the Political Right

- 3.8 Political Ideologies That Reject Political Ideology: Scientific Socialism, Burkeanism, and Religious Extremism

- 4.1 The Freedom of the Individual

- 4.2 Constitutions and Individual Liberties

- 4.3 The Right to Privacy, Self-Determination, and the Freedom of Ideas

- 4.4 Freedom of Movement

- 4.5 The Rights of the Accused

- 4.6 The Right to a Healthy Environment

- 5.1 What Is Political Participation?

- 5.2 What Limits Voter Participation in the United States?

- 5.3 How Do Individuals Participate Other Than Voting?

- 5.4 What Is Public Opinion and Where Does It Come From?

- 5.5 How Do We Measure Public Opinion?

- 5.6 Why Is Public Opinion Important?

- 6.1 Political Socialization: The Ways People Become Political

- 6.2 Political Culture: How People Express Their Political Identity

- 6.3 Collective Dilemmas: Making Group Decisions

- 6.4 Collective Action Problems: The Problem of Incentives

- 6.5 Resolving Collective Action Problems

- 7.1 Civil Rights and Constitutionalism

- 7.2 Political Culture and Majority-Minority Relations

- 7.3 Civil Rights Abuses

- 7.4 Civil Rights Movements

- 7.5 How Do Governments Bring About Civil Rights Change?

- 8.1 What Is an Interest Group?

- 8.2 What Are the Pros and Cons of Interest Groups?

- 8.3 Political Parties

- 8.4 What Are the Limits of Parties?

- 8.5 What Are Elections and Who Participates?

- 8.6 How Do People Participate in Elections?

- 9.1 What Do Legislatures Do?

- 9.2 What Is the Difference between Parliamentary and Presidential Systems?

- 9.3 What Is the Difference between Unicameral and Bicameral Systems?

- 9.4 The Decline of Legislative Influence

- 10.1 Democracies: Parliamentary, Presidential, and Semi-Presidential Regimes

- 10.2 The Executive in Presidential Regimes

- 10.3 The Executive in Parliamentary Regimes

- 10.4 Advantages, Disadvantages, and Challenges of Presidential and Parliamentary Regimes

- 10.5 Semi-Presidential Regimes

- 10.6 How Do Cabinets Function in Presidential and Parliamentary Regimes?

- 10.7 What Are the Purpose and Function of Bureaucracies?

- 11.1 What Is the Judiciary?

- 11.2 How Does the Judiciary Take Action?

- 11.3 Types of Legal Systems around the World

- 11.4 Criminal versus Civil Laws

- 11.5 Due Process and Judicial Fairness

- 11.6 Judicial Review versus Executive Sovereignty

- 12.1 The Media as a Political Institution: Why Does It Matter?

- 12.2 Types of Media and the Changing Media Landscape

- 12.3 How Do Media and Elections Interact?

- 12.4 The Internet and Social Media

- 12.5 Declining Global Trust in the Media

- 13.1 Contemporary Government Regimes: Power, Legitimacy, and Authority

- 13.2 Categorizing Contemporary Regimes

- 13.3 Recent Trends: Illiberal Representative Regimes

- 14.1 What Is Power, and How Do We Measure It?

- 14.2 Understanding the Different Types of Actors in the International System

- 14.3 Sovereignty and Anarchy

- 14.4 Using Levels of Analysis to Understand Conflict

- 14.5 The Realist Worldview

- 14.6 The Liberal and Social Worldview

- 14.7 Critical Worldviews

- 15.1 The Problem of Global Governance

- 15.2 International Law

- 15.3 The United Nations and Global Intergovernmental Organizations (IGOs)

- 15.4 How Do Regional IGOs Contribute to Global Governance?

- 15.5 Non-state Actors: Nongovernmental Organizations (NGOs)

- 15.6 Non-state Actors beyond NGOs

- 16.1 The Origins of International Political Economy

- 16.2 The Advent of the Liberal Economy

- 16.3 The Bretton Woods Institutions

- 16.4 The Post–Cold War Period and Modernization Theory

- 16.5 From the 1990s to the 2020s: Current Issues in IPE

- 16.6 Considering Poverty, Inequality, and the Environmental Crisis

Ancillary Material

About the book.

Designed to meet the scope and sequence of your course, OpenStax Introduction to Political Science provides a strong foundation in global political systems, exploring how and why political realities unfold. Rich with examples of individual and national social action, this text emphasizes students’ role in the political sphere and equips them to be active and informed participants in civil society. Learn more about what this free, openly-licensed textbook has to offer you and your students.

About the Contributors

Dr. Mark Carl Rom is an associate professor of government and public policy at the McCourt School of Public Policy and the Department of Government. His recent research has focused on assessing student participation, improving grading accuracy, reducing grading bias, and improving data visualizations. Previously, Rom has explored critiques and conversations within the realm of political science through symposia on academic conferences, ideology in the classroom, and ideology within the discipline. He continues to fuel his commitment to educational equity by serving on the AP Higher Education Advisory Committee, the executive board of the Political Science Education section (ASPA), and the editorial board of the Journal of Political Science Education. Prior to joining McCourt, Rom served as a legislative assistant to the Honorable John Paul Hammerschmidt of the US House of Representatives, a research fellow at the Brookings Institution, a senior evaluator at the US General Accounting Office, and a Robert Wood Johnson Scholar in Health Policy Research at the University of California, Berkeley. His dissertation, “The Thrift Tragedy: Are Politicians and Bureaucrats to Blame?,” was the cowinner of the 1993 Harold Lasswell Award from the American Political Science Association for best dissertation in the public policy field. Rom received his BA from the University of Arkansas and his MA and PhD in political science from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1992.

Masaki Hidaka has a master of public policy from the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, where she wrote her thesis on media coverage of gaming ventures on Native American tribal lands. She completed her PhD at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania, where her dissertation examined the relationship between issue publics and the Internet. She is currently a professorial lecturer at the School of Public Affairs at the American University in Washington, DC, but has taught in numerous institutions, including the National University of Singapore, University College London, and Syracuse University in London. She also worked as a press aide for former San Francisco mayor Willie L. Brown Jr. (and she definitely left her heart in San Francisco).