Rethinking Schools

The History of Sexuality Education

By Priscilla Pardini

The 1960s saw the beginning of the current wave of controversy over sex ed in U.S. schools. But as early as 1912, the National Education Association called for teacher training programs in sexuality education.

In 1940, the U.S. Public Health Service strongly advocated sexuality education in the schools, labeling it an “urgent need.” In 1953, the American School Health Association launched a nationwide program in family life education. Two years later, the American Medical Association, in conjunction with the NEA, published five pamphlets that were commonly referred to as “the sex education series” for schools.

Support for sexuality education among public health officials and educators did not sway opponents, however. And for the last 30 years, battles have raged between conservatives and health advocates over the merits — and format — of sexuality education in public schools.

The first wave of organized opposition, from the late 1960s to the early 1980s, took the form of attacks aimed at barring any form of sex ed in school. Sex education programs were described by the Christian Crusade and other conservative groups as “smut” and “raw sex.” The John Birch Society termed the effort to teach about sexuality “a filthy Communist plot.” Phyllis Schlafly, leader of the far-right Eagle Forum, argued that sexuality education resulted in an increase in sexual activity among teens.

Efforts to curtail sex ed enjoyed only limited success, however. Sex education programs in public schools proliferated, in large part due to newly emerging evidence that such programs didn’t promote sex but in fact helped delay sexual activity and reduce teen pregnancy rates.

By 1983, sexuality education was being taught within the context of more comprehensive family life education programs or human growth and development courses. Such an approach emphasized not only reproduction, but also the importance of self-esteem, responsibility, and decision making. The new courses covered not only contraception, but also topics such as family finances and parenting skills.

In the mid 1980s, the AIDS epidemic irrevocably changed sexuality education. In 1986, U.S. Surgeon General C. Everett Koop issued a report calling for comprehensive AIDS and sexuality education in public schools, beginning as early as the third grade. “There is now no doubt that we need sex education in schools and that it [should] include information on heterosexual and homosexual relationships,” Koop wrote in his report. “The need is critical and the price of neglect is high.”

But if Koop’s report helped promote sexuality education, it also forced the Religious Right to rethink its opposition strategies. Even the most conservative of sex-ed opponents now found it difficult to justify a total ban on the topic. Instead, the Right responded with a new tactic: fear-based, abstinence-only sexuality education.

Included in:

Volume 12, No.4

Summer 1998.

How AIDS Changed the History of Sex Education

I t was September of 1986 when U.S. Surgeon General C. Everett Koop announced that the country had to change course on sex education. By then, however, the change had already begun.

Whether and how sex should be taught in public schools wasn’t exactly a new topic of discussion but, even as many programs began to move away from the straightforward facts of biology in order to get into the real experience of young sexuality, some details remained taboo. Was it O.K. to acknowledge homosexuality? Was it O.K. to talk about sexual acts unrelated to reproduction? And how young was too young?

Those questions could have been debated indefinitely; the metaphor of a pendulum is often used to describe changing attitudes toward sexual mores and education. Until something came along that made those questions seem less important than ever: AIDS. In the 1980s, even before Koop spoke out, fear of the then-mysterious disease gave parents, educators, politicians and students a reason to put aside their sqeamishness — and thus changed the history of sex ed forever. Which was where Koop came in, as TIME reported in a 1986 cover story by John Leo:

“There is now no doubt,” said Surgeon General C. Everett Koop in his grim report on AIDS last month, “that we need sex education in schools and that it must include information on heterosexual and homosexual relationships.” With characteristic bluntness, Koop made it clear that he was talking about graphic instruction starting “at the lowest grade possible,” which he later identified as Grade 3. Because of the “deadly health hazard,” he said later, “we have to be as explicit as necessary to get the message across. You can’t talk of the dangers of snake poisoning and not mention snakes.”

A poll accompanying the story found that the longstanding figure that 80% of Americans were in favor of public-school sex ed was out of date; it had jumped to 86%. Harvey Fineberg of Harvard’s School of Public health told the magazine that sex ed had become “a matter of life and death” and, even though not everyone agreed on what exactly should be included in such a class, particularly the question of whether to focus on abstinence, it was getting hard to argue that the topic should be avoided completely. (The “death” part was the only thing that was actually new; sex ed has always been a matter of life.) A full 95% of respondents to the TIME survey answered that they thought that 12-year-olds should be taught about the dangers of AIDS — nearly 20 percentage points more than answered yes to the question of whether kids that age should be taught “how men and women have sexual intercourse.” As a result, formerly off-limits subjects like anal sex were introduced to classrooms around the country.

By the time the magazine revisited the topic in 1993, a whopping 47 states mandated some form of sex ed for students — versus a mere three in 1980 — and every single state supported education about AIDS.

During the ’90s, sex ed programs grew, the teen birth rate sank and teens began to have less sex overall. As of 2002, TIME reported that “a quarter of all new HIV cases today occur in those ages 21 and younger” — and, as of 2010, that figure hadn’t changed much, with the CDC reporting that 26% of new infections were in people between the ages of 13 and 24. But that doesn’t mean that nothing has changed. Instead of sex ed ending HIV infection among teenagers, treatment for AIDS became a reality and the syndrome stopped being the conversation-ender it once was, freeing parents and educators to go back to war over what should be taught when. Today, fewer than half as many states as did 20 years ago require that public-school students get sex ed in the classroom.

The pendulum, it appears, continues to swing.

Read more: Why Schools Can’t Teach Sex Ed in the Internet Age

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Biden’s Campaign Is In Trouble. Will the Turnaround Plan Work?

- Why We're Spending So Much Money Now

- The Financial Influencers Women Actually Want to Listen To

- Breaker Sunny Choi Is Heading to Paris

- The UAE Is on a Mission to Become an AI Power

- Why TV Can’t Stop Making Silly Shows About Lady Journalists

- The Case for Wearing Shoes in the House

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Lily Rothman at [email protected]

You May Also Like

- The Open University

- Guest user / Sign out

- Study with The Open University

My OpenLearn Profile

Personalise your OpenLearn profile, save your favourite content and get recognition for your learning

A brief history of sex education

Find out more about The Open University's Health and Wellbeing courses and qualifications.

There is still a great deal we don’t know about the history of sex education. The research that has been done is largely about school sex education during the 20th century. School sex education is important, yet most of us learn little of what we know about sex from our schooling. We learn it from friends, from family and, increasingly, from the media.

In England from the late 19th century, a number of sex education publications were produced, mainly aimed at helping parents to enlighten their children. However, in school, little formal school sex education took place before the Second World War. What there was often took place in the context of ‘hygiene’. There are references from the 1920s to senior girls being provided with instruction on such topics as ‘self-reverence, self control and true modesty’, and to boys, on leaving schools, being given talks on the ‘temptation of factory and workshop life’, with special reference to sex.

The significance of the Second World War The Second World War had, of course, huge consequences for the lives of most of the population of Europe and a considerable number of countries beyond. It is often the case that the mass movement of people, particularly soldiers, results in an increase in the incidence of sexually transmitted infections. As one might expect, then, the outbreak of the war seems to have resulted in an increase in school sex education and a shift, in one of the aims of sex education, towards the prevention of syphilis and gonorrhoea.

The 1950s and 1960s Anecdotal accounts of lessons on the reproductive systems of rabbits, or the pollination of flowering plants, suggest that much school sex education in the UK in the 1950s and ‘60s, was carried out through the descriptions, though not the observations, of the reproductive habits of plants and non-human animals. It seems likely that boys, especially if educated in the public school (i.e. fee-paying) boarding system, may still have sometimes received warnings about the dangers believed to follow from masturbation.

At the same time, teaching about the human reproductive system became much more typical than it had previously been. Sex education was largely seen as teaching about reproduction and so undertaken in biology lessons. Biology was widely perceived as a more suitable subject for girls than for boys, and girls were more likely than boys to receive school sex education.

The 1970s and 1980s By the start of the 1970s, school sex education was beginning to change significantly, no doubt largely in response to the great social changes of the 1960s and ‘70s. Biology textbooks started to provide fuller accounts of the human reproductive systems, while methods of contraception began to be taught more widely. The emphasis was mostly on the provision of accurate information, and aims of sex education programmes included a decrease in ignorance, guilt, embarrassment and anxiety. Issues to do with relationships were probably more often discussed in programmes of personal and social education, or their equivalents, rather than in biology lessons.

The 1980s continued to see an increase in the aims of sex education. The growing acceptance of feminist-thinking led to an increase in the number of programmes that encouraged pupils to examine the roles played by women and men in society. The aim was typically for students to realise the existence and extent of gender inequality. Feminist critiques of sex education programmes pointed out how such programmes sometimes actually reinforced gender inequalities. It began more widely to be appreciated just how often the discourse of sex education served to perpetuate the belief that male self-control, though possible, could not be relied on, and that women, by their behaviours, should help men to act responsibly.

At the same time, sex education programmes increasingly began to have such aims as the acquisition of skills for decision-making, communicating, personal relationships, parenting and coping strategies. However, it is probably the case that most pupils continued to receive little school sex education, and that what they did receive was a rather brief and narrow education, in biology lessons, about puberty and human reproduction. It is clear that few pupils were given much opportunity to discuss anything about sexual feelings and relationships.

Nevertheless, as the importance of skills became acknowledged, so sex education programmes increasingly talked about enabling young people to think for themselves and make their own informed decisions about issues that concerned their sexuality. It was this sort of language that so alarmed many conservative commentators and legislators, on account of what was perceived as the increasing liberalisation of school sex education.

HIV/AIDS The post-Second World War advent of antibiotics meant that for several decades a fear of sexually transmitted infections played only a minor role in the thinking behind most school sex education programmes. This situation changed suddenly, in the mid-1980s, when it was realised that a new sexually transmitted agent - HIV was rapidly spreading in many countries of the world. Near panic set in, in some quarters, as it became appreciated that many, perhaps most, people infected with HIV would go on to develop AIDS and subsequently die. Also that a person could be infected with HIV, and thus infectious, for many years without realising it or having any symptoms of infection, and that there was no treatment either for HIV infection or for AIDS itself.

HIV and AIDS became a health issue in the UK at just the time that sex education became a political football. A number of circumstances, including the controversy over the 1985 Gillick case, which focused on whether parents always have the right to know if their children are being issued with contraceptives when under the age of 16, and the growing strength of the lesbian and gay movement, led to a polarisation of views on sex education, among politicians at local and national level. A flurry of legislation and government education circulars, which continues to this day, resulted, and it increasingly became acknowledged that a values-less sex education programme cannot exist.

Politics and sex education There are interesting differences between countries in the extent to which national politics have affected school sex education. In both the UK and the USA, national politics have been extremely influential with a small but powerful lobby believing that much school sex education is corruptive. As Baroness Strange, speaking in a parliamentary debate about school sex education in 2000, put it “Yesterday, when I was kneeling in the snowdrops, in the woods at home, picking fresh white blossoms with their sharp, sweet scent, they made me think of the innocence, purity and loveliness of children”.

In the Netherlands, on the other hand, sex education has remained remarkably non-political. It has been argued that this has led, in the Netherlands, to a much more coherent programme of school sex education, in which teachers are not worried that they may be blamed for teaching something that they shouldn’t be. Whether this is partly responsible for the fact that a teenage girl in the UK or USA is about 10 times as likely to become pregnant than in the Netherlands is controversial.

Recent and current school sex education Recent school sex education programmes have varied considerably in their aims. At one extreme (rarely found in the UK but well-funded and widespread in the USA), abstinence education aims to ensure that young people do not engage in heavy petting or sexual intercourse before marriage. At the other end of the spectrum, some sex education programmes challenge sexist and homophobic attitudes, try to help young people make their own decisions about their sexual behaviour and discuss issues of sexual pleasure.

Indeed, the present UK government has been much more positive than its conservative predecessors about attempting to introduce a more inclusive approach to sex education. It has begun to issue guidance to schools on how to tackle homophobic bullying and, while still supporting marriage, has tried to distance itself from the position that children brought up in homes where parents are not married, as is, of course, increasingly the case, are living in second-rate families.

Learn more about sex

Do animals have sex for fun?

How was it for Fido? Do animals approach sex in more than a - well, animalistic - way?

Why school-based sex education isn’t inclusive enough

Only a small minority of LGBT young people learn about sexual health in the classroom, which could put them at risk.

Study a free course

Supporting children's development

Supporting children’s development is an introductory course for anyone who is interested in children’s development, especially support staff in schools, such as teaching assistants. It builds on your knowledge and skills to develop a deeper understanding of children from the early years to school leavers. You will be introduced to some core ...

Introduction to child psychology

Childhood is a time of rapid growth and development, and studying these changes is endlessly stimulating. In this free course, Introduction to child psychology, you will be introduced to the discipline of child psychology and some of the key questions that guide the understanding of childhood. These questions include 'What influences children's...

Young people’s wellbeing

What do we mean by 'wellbeing' for young people? How is it shaped by social differences and inequalities, and how can we improve young people's mental and physical health? This free course, Young people's wellbeing, will examine the range of factors affecting young people's wellbeing, such as obesity, binge drinking, depression and behavioural ...

Become an OU student

Ratings & comments, share this free course, copyright information, publication details.

- Originally published: Sunday, 4 July 2010

- Body text - Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 : The Open University

- Image 'Introduction to child psychology' - Copyright free

- Image 'Do animals have sex for fun?' - Copyright free: htraue

- Image 'Young people’s wellbeing' - Copyright: Photo by Kenex Media sa from Pexels

- Image 'Why school-based sex education isn’t inclusive enough' - Virhemarginaali Podcast under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 license

- Image 'Supporting children's development' - Chris Steer/iStockphoto.com under Creative-Commons license

Rate and Review

Rate this article, review this article.

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews

For further information, take a look at our frequently asked questions which may give you the support you need.

- Anti-Abortion Movement

- Women’s History

- Film & TV

- Gender Violence

- #50YearsofMs

More Than A Magazine, A Movement

The History of Sex Ed: From Awkward and Exclusionary, to Affirmative and Empowering

Siecus’s history of sex education narrates the trajectory of sex ed over the last several decades, revealing how mainstream curricula responded to specific economic and political objectives..

Many of us remember where we were when we first heard the dreaded words “sex education.” Whether it was in an elementary or middle school classroom, a doctor’s office, a church basement, or our own homes, we recall how it felt to learn about s-e-x.

For some of us, our experience with sex ed curriculum put embarrassing and taboo feelings about our bodies and desires front and center in a public forum. For others, the experience may have provoked past traumas related to sexual violence. And many sex education programs alienated and invalidated generations of youngsters whose identities and sexual orientations fell outside the rigid “norms” presented in mainstream learning materials.

I still vividly remember a “petting” progression graph our 6th grade gym teacher presented on the overhead projector. As we sat silently in the dark, she warned “heavy petting” would inevitably escalate into penetrative sex—and, by extension, STIs or unwanted pregnancy. I’ll admit that lesson’s takeaway had a profound impact on my sexuality, particularly my sexual agency as a young woman: Without accompanying messages about consent and sexual rights, I interpreted the graph as a mandate obliging me to “go all the way” once I passed the point of no return. Such harmful teachings taught generations of women that their bodies and sexual power were subordinate to male desire. I can scarcely imagine how this heteropatriarchal schema resonated with my LGBTQ+ peers.

SIECUS Outlines the History of Sex Education

As tweens and teens, most of us had little awareness of the ideologies and imperatives shaping what we learned in the sex ed classroom. Even as adults we may not fully grasp how the social and political agendas of the day permeate sex education. Recently, the nonprofit organization, SIECUS: Sex Ed For Social Change , issued a report detailing the evolution of sex ed curricula in the United States. Launched in March in honor of Women’s History Month, the report surveys the history of sex education from the early 20th century to the present.

Founded by Dr. Mary S. Calderone in 1964, SIECUS has worked to transform sex education into a critical tool for social justice. Their mission acknowledges “sex ed sits as the nexus of many social justice movements—from LGBTQ+ rights and reproductive justice to the #MeToo movement and the urgent conversations around consent and healthy relationships.”

Their newest resource, History of Sex Education , provides an accessible overview of the field’s evolution, as well as its future directions. As the report narrates the trajectory of sex ed over the last several decades, it reveals how mainstream curricula responded to specific economic and political objectives. For much of the early 20th century, sex education served to maintain social order and reinforce the interlocking systems of capitalism, patriarchy and white supremacy. For example, the earliest sex educators used moralistic and “social hygiene” teachings to combat what they saw as the “social ills” that threatened public health, reproduction and traditional marriage.

If you found this article helpful, please consider supporting our independent reporting and truth-telling for as little as $5 per month.

Strikingly, all of these teachings presumed that women had no sexual desires beyond what was necessary for procreation. Educational campaigns and propaganda convinced young women to focus on marriage and motherhood, not sexual pleasure.

At the same time, sex ed proponents blamed communities of color, particularly African Americans, for spreading disease and sexual “vice.” Citing historian Courtney Q. Shah , the report demonstrates how early sex education efforts “normalized white male (middle class) sexuality and pathologized any departures from the white male norm.”

To be sure, these teachings also rejected all forms of non-heteronormative sex and even warned that female friendships might lead to lesbianism. Generations of U.S. public school students learned that homosexuality was a mental disorder and antithetical to the ‘American dream.’ For much of the 20th century, homosexual sex remained criminalized under “ sodomy laws .” While most U.S. states repealed these laws in the 1970s, it would take two more decades for the World Health Organization to declassify homosexuality as a mental disorder.

SIECUS Seeks to Redefine Sex as a Social Good

SIECUS’s founding in the early ’60s began transforming the landscape of sexual education in the United States. The organization’s founders, mostly medical professionals, aimed to free sex from the Victorian-influenced sensibilities of the early 20th century.

Perhaps ahead of its time, SIECUS sought to redefine sex as a social good and a natural “creative and recreative” part of human life. Unfolding amidst the ‘sexual revolution,’ SIECUS’s curriculum moved beyond earlier models of teaching that emphasized behavior control and the suppression of sexuality. Serendipitously, as sex moved into mainstream popular culture in the ’60s, parents and school systems saw a distinct need for sex education.

Yet, with each step forward, sex education attracted vociferous opponents. The rise of second-wave feminism and the civil rights movement, shifting gender roles, and the introduction of the birth control pill stoked fears among conservative factions. Far-right political and religious groups like the John Birch Society and the Christian Crusade began vilifying sex education. They argued that informing youngsters about sex would dismantle traditional marriage and secularize society. SIECUS and its founder, Dr. Mary Calderone, became favored targets for conservative stalwarts who, like their predecessors, wanted to maintain white Christian heteronormativity and patriarchy. These “moral crusaders” ignited what would become a decades-long culture war over sex education.

SIECUS continued promoting accessible and comprehensive sex education in the face of the AIDS epidemic and the rise of the Christian-right’s “abstinence-only” legislation. Part of their work in the 1990s included the introduction of flexible curricula that local educators could adapt to the needs of their communities. This effort also resulted in the release of Spanish-language learning materials.

SIECUS advocates worked closely with policymakers to expose the ineffective and exclusionary effects of “abstinence-only” programming throughout the late 1990s and early 2000s. They argued the implementation of these curricula were “nothing more than a social agenda masquerading as teen pregnancy and STI prevention.” A cascade of data soon emerged proving the correlation between “abstinence-only” programs and higher rates of teen pregnancy and STI.

Today, SIECUS continues to champion more inclusive and sex-positive education for all. Their advocates argue that sex education acts as one among many “vehicles for social change.” In recent years, SIECUS has integrated more intersectional perspectives to create more justice-oriented, transformative sex education curricula. With this lens, SIECUS advocates hope to empower the next generation with knowledge about their bodies, desires and identities.

The Future of Sex Ed

The field of sex education owes much to SIECUS’s advocacy over the last half century. Though we’ve moved away from “petting” graphs of yesteryear, sex ed proponents still face daunting challenges for advancing towards more empowering and inclusive outreach. Perhaps most urgently, the field must counter the onslaught of harmful legislation aimed at denying LGBTQ+ adolescents access and rights to health care and other opportunities, such as athletics . For decades SIECUS has led the charge to give voice and make space for the most marginalized groups and will no doubt rise to the challenge again.

You may also like:

Lil Nas X, Gender Nonconformity and the Fight Against Transphobic Legislation

Let’s Talk About Sex (Education)

Today in Feminist History: Sex Education is not “Obscene” (April 29, 1929)

About Cari Maes

You May Also Like:

Don’t Say Rape: How the Book Banning Movement Is Censoring Sexual Violence

Your Top Questions on Abortion and Birth Control, Broken Down

Sex Education

The idea that schools and the state have a responsibility to teach young people about sex is a peculiarly modern one. The rise of sex education to a regular place in the school curriculum in the United States and Western Europe is not, however, simply a story of modern enlightenment breaking through a heritage of repression and ignorance. Rather, the movements for sex education can be understood from several related angles: as part of larger struggles in the modern era over who determines the sexual morality of the coming generation; as part of the persistent tendency to view ADOLESCENCE –especially adolescent SEXUALITY –as uniquely dangerous; and as part of the broader historical tendency for more and more realms of personal life to come under rational control. Sex education has always been shaped by its historical context.

It is worth noting that formal sex education has never held a monopoly on sexual information. Much to the distress of sex educators, young people do not simply memorize their school lessons and apply them perfectly. They have always cobbled together their own understanding of their (and others') bodies out of their personal experiences and an accidental agglomeration of "official" sex education, parental teaching, playground mythology, popular culture, and even pornography.

Early History

Prior to the twentieth century, sex education was even more haphazard. Most Americans and Europeans lived in the countryside, where chance observation of animal behavior provided young people with at least a measure of information about reproductive sexuality. Beyond that, education was mixed. Given the expectation that girls would remain chaste until their wedding night, sex education for them did not seem pressing until the eve of matrimony, when their mothers were supposed to sit them down and explain sex and reproduction; contrary expectations for boys often meant that a young man's male relatives or co-workers would take him to a brothel to initiate him into the mysteries of sex.

In the 1830s, however, various health reformers and ministers in the United States and in England began to publish a flood of pamphlets and books to inform and fortify the young man who left home for school or a job. These works were typically great stews of theological, nutritional, and philosophical information, but all aimed to help readers control their sexual urges until they could be safely expressed in marriage. More particularly, these early sex educators tended to be obsessed with the dangers of MASTURBATION . For example, the health reformer Sylvester Graham's 1834 Lecture to Young Men and the Reverend John Todd's 1845 The Young Man. Hints Addressed to the Young Men of the United States followed works by the English physician William Acton in warning that the "solitary vice" (i.e., masturbation) could and probably would lead to a physical and mental breakdown–even death. The literature seldom addressed women, as society generally considered them to be at all times under the protection of their parents and then their husbands, while young men were more mobile. In France, the sex education literature that began appearing in the 1880s, was usually addressed to bourgeois mothers, and focused chiefly on their duty to instruct their daughters on the dual need to be chaste until marriage but prepared for sexual contact after matrimony. Despite these small steps toward education, later reformers complained that a "conspiracy of silence" about sexual matters existed into the early years of the twentieth century.

Origins of a Movement

The formal movement for sex education commenced in the early twentieth century. Oddly, early reformers seldom said anything about needing to compensate for the loss of barnyard knowledge when families grew up in the city rather than on a farm. In other societies undergoing rapid urbanization, such as China at the dawn of the twenty-first century, newspapers regularly reported on young city couples who wanted children for years but never picked up the essential information on animal breeding that would have suggested how to become pregnant. American reformers, like their counterparts in England at roughly the same time, were more focused on the related dangers of medical and moral decline. First, physicians were growing alarmed about the impact of syphilis and gonorrhea–the "venereal diseases"–among all classes of citizens, and among women as well as men. Investigators had come to recognize that these sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) annually caused thousands of cases of pelvic inflammation, sterility, infant blindness, and even insanity. Second, physicians and their allies associated this "epidemic" with what many Americans considered the immorality of life in the city. Native-born Americans in particular believed that a moral crisis loomed in cities such as Chicago and New York as immigrants and migrants from the countryside crowded together in dismal tenements and children grew up without the "ennobling influence" of life on the farm. Equally alarming, in an era in which prostitution was a fairly open secret in the red light districts of most urban areas, doctors became convinced that the majority of STDs were transmitted through men visiting prostitutes. This meshing together of moral and medical concepts was to remain characteristic of American and, to a lesser extent, European sex education.

Sex education became a significant part of the response to these twin anxieties. Founded in 1914 by the New York physician Prince Morrow and the religious crusader Anna Garlin Spencer, the American Social Hygiene Association (ASHA) quickly took the lead in recommending reforms to accomplish the twin goals of medical and moral improvement. After leading police crackdowns on prostitution and presenting a series of sex education lectures to adults, ASHA and related societies proposed a program in "sex instruction" for high-school-age youth. ASHA's leaders hoped they could reach young people with proper "scientific" facts about sex before they were "corrupted" by harmful misinformation, such as the widely held belief that young men suffered from a "medical necessity" to have sex. If citizens only knew the medical dangers of sexual immorality, reformers believed, then they would rationally decide not to experiment with prostitution or promiscuity.

Although the English movement for sex education grew out of similar anxieties, and was led by a similar combination of medical and moral authorities, the French movement differed in certain essential respects. France officially tolerated and regulated prostitution, for example, so it never became a focus of educators' efforts. Instead, French sex educators were more concerned about preparing young middle-class women for the sexual aspects of marriage and reproduction. They generally ignored working-class females, believing they were already immoral by nature. French authorities occasionally supported sex education for men to combat the scourges of STDs, but after the carnage of World War I, French educators also linked sex education to the need for French families to bear more children to repopulate the state.

Moving into the Schools

Sex educators in the United States sometimes experimented with working through parents, churches, and public lectures, but they quickly turned to the public schools. In the early twentieth century, public school attendance was exploding as compulsory education laws and the changing structure of the economy pressured more students into the classroom and kept them there longer. At the same time, observers were becoming more conscious of youth as a period of life separate from adulthood, with its own particular needs and dangers, and this new conception of the adolescent was widely popularized by the publication of G. S TANLEY H ALL ' sessential Adolescence in 1904. Trapped between the sexual awakening of PUBERTY and the "legitimate" sexual outlet of marriage, adolescents seemed particularly to need careful guidance, and the public schools could step in to give it to them where parents seemed to be failing. Not coincidentally, moving their mission to the classroom promised to give sex educators a captive audience.

Reflecting their own uneasiness with sexuality, the early sex educators constructed a program whose central mission was to quash curiosity about sex. Initially, the sex education program consisted of an outside physician delivering a short series of lectures outlining the fundamentals of the reproductive system, the destructive power of syphilis and gonorrhea, and the moral and medical dangers caused by sex before or outside of marriage. Boys and girls sat in separate classrooms, and their lessons reflected a strong sense of difference between the sexes. Besides hearing the medical warnings about sexually transmitted diseases, boys learned that they had a moral responsibility to their mothers and future wives to remain chaste. Girls were instructed much more deliberately in raw fear–especially in the high likelihood of contracting syphilis from a male. So vivid were the warnings that some instructors in the first decades of the twentieth century actually worried that their female students might never marry. Because they sought to ennoble sexuality by making it synonymous with reproduction, early sex educators seldom dwelled on the threat of TEEN PREGNANCY .

Despite the educators' moralistic tone, sex education met immediate opposition. When Chicago became the first major city to implement sex education for high schools in 1913, the Catholic Church in particular led a powerful attack on the program and helped secure the resignation of its sponsor, Ella Flagg Young, the famous superintendent of schools.

The Chicago controversy, as it was called, laid out the themes that were to characterize the politics of sex education in the United States over the next century. Both supporters and opponents agreed that youthful sexuality was a problem. But where supporters felt that "scientific" knowledge about sexuality (or at least reproduction) would lead young people down the path to moral behavior, opponents argued that any suggestion of sexuality, no matter how well intended, would corrupt students' minds.

The federal government first became involved in sex education during World War I, when the Chamberlain-Kahn Act of 1918 first earmarked money to educate soldiers about syphilis and gonorrhea. Over half a million young men had their first experience with sex instruction in the war. ASHA later took many of the materials its consultants had developed for the military, such as the film Fit to Fight, and adapted them for public school use by editing out the segments on prophylaxis. Until the 1950s, the federal government remained involved in sex education, mainly through the U.S. Public Health Service, emphasizing the medical and moral dangers of sexually transmitted diseases.

More than Hygiene

In the Jazz Age of the 1920s, sex education made progress into the curriculum both in the United States and in France. American sex education typically took place in high school biology classes, but leaders in the movement also faced for the first time a clear divergence between adult sexual ideals and society's expectations for youth. Up to the early twentieth century, when sexual fulfillment was not considered a public or respectable ideal even for married adults, it was easy for educators to condemn sex in their lessons. But in the 1920s, as more Americans came to believe that sexual fulfillment was a crucial part of marriage, educators faced the dilemma of recognizing that sex was a positive force in marriage while at the same time needing to condemn its expression among the unmarried. Sex educators responded partly by reemphasizing the health dangers of sex outside of marriage, but also by incorporating the new ideals. Greatly concerned over the sexual freedom of the "new youth" in the 1920s and 1930s, sex educators appealed to psychology and sociology for evidence that sexual experimentation before marriage endangered a youth's chances for a fulfilling wedded life.

After the discovery of penicillin's uses in World War II lessened the danger of syphilis, ASHA and its allies focused more directly on the social aspects of sexuality and married life. Known by a variety of names, the new "family life education" represented an expansion of the educators' mission. Instead of teaching mostly about sexual prohibitions, family life educators attempted to instruct students in the positive satisfactions to be gained from a properly ordered family life. Lessons on child rearing, money management, wedding planning, DATING , and a wide variety of other daily tasks were intended to bring a new generation of American youth into conformity with white, middle-class norms.

In response particularly to the "sexual revolution" of the 1960s and 1970s, in which rates of premarital sexual activity, pregnancy, and sexually transmitted diseases climbed steeply, sex educators developed what they called "sexuality education," to distinguish their approach from the overt moralizing and narrow heterosexual focus of its predecessors. The leaders in sexuality education, such as the Sexuality Information Education Council of the United States (SIECUS, founded in 1964), believed that teaching about sexuality in a value-neutral manner would allow students to reach their own conclusions about sexual behavior and sexual morality. Sexuality education was intended to include information on BIRTH CONTROL methods, teenage pregnancy, masturbation, gender relations, and, eventually, HOMOSEXUALITY . Although value-neutral sexuality education generally avoided the overt moralizing of its predecessors, it nevertheless stacked the deck in favor of traditional morality–abstinence until heterosexual marriage.

Despite its generally traditional message, sexuality education quickly aroused a firestorm of opposition. Beginning in 1968, conservative groups and previously apolitical religious activists mobilized to attack what one pamphlet called "raw sex" in the schoolhouse. Opponents were offended not only by sexuality education's greater explicitness, but by its refusal to drill students in "proper" sexual morality. Sexuality education seemed to represent a wide variety of liberal attitudes that were beginning to appear in American society, and the struggles over sexuality education helped motivate a new generation of religious conservatives to enter American politics in the 1970s. It was at this point that the American experience began to diverge from the European approach, which had aroused occasional Catholic disapproval but never faced a highly political campaign of opposition.

HIV/AIDS Crisis

In the United States, the debate between opponents and supporters continued to follow the same lines until the pandemic of Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS) began in the 1980s. As the magnitude and deadliness of this sexually transmitted illness became known (and as the public became aware that heterosexuals as well as homosexuals were at risk), sex educators found their position bolstered. By the mid-1990s almost every western European nation sponsored fairly explicit educational programs in "safe sex"; in the United States, every state had passed mandates for AIDS education, sometimes combined with sexuality education, sometimes as a stand-alone program. AIDS provided crucial justification for the more liberal sexuality educators' inclusion of information on contraception, homosexuality, and premarital sex. At universities and many high schools, students also started "peereducation" groups to offer students a sex education message that was even less hierarchical and judgmental (and sometimes much more explicit). Despite a renewed conservative attack on these programs, sexuality education's place seemed to have become secure.

As conservative opponents in the United States came to recognize that some form of sex education was going to be almost inevitable, they launched their own movement to replace sexuality education with "abstinence education." Religious conservatives, in particular, helped add provisions for abstinence education to the 1996 W ELFARE R EFORM A CT , and the federal government for the first time began to direct tens of millions of dollars to abstinence education programs, most of which were tied to religious groups rather than the more traditional public health organizations. Unlike sexuality education's value neutrality, abstinence education was directly moralistic and explicitly supported traditional gender and sexual relations. Abstinence education also harked back to the early years of sex education in its strong emphasis on the dangers of sexual activity. Many curricula intentionally omitted or distorted information about protective measures such as condoms or birth-control pills. Again, this contrasted with the European experience, in which sexuality education was firmly under the control of secular medical authorities and faced little religious or political challenge.

International Context

Outside of Western Europe and the United States, sex education remained largely informal until concerns over a population explosion and the AIDS crisis prompted international organizations such as the United Nations to become involved in educating residents in Africa and South Asia particularly about contraception and prophylaxis. Although the religious opposition there has been muted, educators have often met with resistance from governments unwilling to admit that their populations were experiencing problems with AIDS, and from male traditionalists reluctant to allow women greater control over their own sexuality. Political battles in the United States, too, have affected the shape of sex education in the less-developed regions of the world, as American conservatives at the dawn of the twenty-first century attempted to use U.S. funding to shift the content of international sex education programs away from contraception and towards abstinence and a more moralistic approach to sexual relations.

The response to the AIDS crisis once again underlined the general tendency to justify sex education as disaster prevention in response to diseases or other "epidemics," such as teenage pregnancy. Throughout the history of sex education, adults in the West have generally treated adolescent sexuality as existing in a different world from its grown-up version, blaming hormones or the youth culture for recurring crises in adolescent sexual behavior. But youthful sexual behavior has almost always been closely tied to adult patterns of behavior: rising rates of extramarital intercourse among adolescents, for example, only followed the same phenomenon among adults; the same held true for the "epidemic" of pregnancy outside of marriage in the 1970s, as pregnant teenage females followed their adult counterparts in having more children outside of wedlock.

Although it has undoubtedly dispelled much ignorance and anxiety among students, sex education in the United States, at least, has generally failed to deliver on its promise to change adolescent sexual behavior. Sexual behavior is a complex phenomenon, and hours in the classroom have seldom managed to counteract the influence of class, race, family, region, and popular culture. Nevertheless, the history of sex education reveals a great deal about modern conceptions of sexuality, adolescence, and authority.

See also: AIDS ; Hygiene ; Venereal Disease .

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bigelow, Maurice A. 1916. Sex-Education: A Series of Lectures Concerning Sex in Its Relation to Human Life. New York: Macmillan.

Chen, Constance M. 1996. "The Sex Side of Life": Mary Ware Dennett's Pioneering Battle for Birth Control and Sex Education. New York: Free Press.

Hall, G. Stanley. 1904. Adolescence: Its Psychology and its Relations to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion, and Education. New York: D. Appleton.

Irvine, Janice. 2002. Talk About Sex: The Battles Over Sex Education in the United States. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Moran, Jeffrey P. 2000. Teaching Sex: The Shaping of Adolescence in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Smith, Ken. 1999. Mental Hygiene: Classroom Films 1945–1970. New York: Blast Books.

Stewart, Mary Lynn. 1997. "'Science is Always Chaste': Sex Education and Sexual Initiation in France, 1880s–1930s." Journal of Contemporary History 32: 381–395.

J EFFREY P. M ORAN

« Series Books

Sexuality »

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

The State of Sex Education in the United States

Kelli stidham hall.

Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia

Jessica McDermott Sales

Kelli a. komro, john santelli.

Department of Population & Family Health, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, New York

For more than four decades, sex education has been a critically important but contentious public health and policy issue in the United States [ 1 – 5 ]. Rising concern about nonmarital adolescent pregnancy beginning in the 1960s and the pandemic of HIV/AIDS after 1981 shaped the need for and acceptance of formal instruction for adolescents on life-saving topics such as contraception, condoms, and sexually transmitted infections. With widespread implementation of school and community-based programs in the late 1980s and early 1990s, adolescents’ receipt of sex education improved greatly between 1988 and 1995 [ 6 ]. In the late 1990s, as part of the “welfare reform,” abstinence only until marriage (AOUM) sex education was adopted by the U.S. government as a singular approach to adolescent sexual and reproductive health [ 7 , 8 ]. AOUM was funded within a variety of domestic and foreign aid programs, with 49 of 50 states accepting federal funds to promote AOUM in the classroom [ 7 , 8 ]. Since then, rigorous research has documented both the lack of efficacy of AOUM in delaying sexual initiation, reducing sexual risk behaviors, or improving reproductive health outcomes and the effectiveness of comprehensive sex education in increasing condom and contraceptive use and decreasing pregnancy rates [ 7 – 12 ]. Today, despite great advancements in the science, implementation of a truly modern, equitable, evidence-based model of comprehensive sex education remains precluded by sociocultural, political, and systems barriers operating in profound ways across multiple levels of adolescents’ environments [ 4 , 7 , 8 , 12 – 14 ].

At the federal level, the U.S. congress has continued to substantially fund AOUM, and in FY 2016, funding was increased to $85 million per year [ 3 ]. This budget was approved despite President Obama’s attempts to end the program after 10 years of opposition and concern from medical and public health professionals, sexuality educators, and the human rights community that AOUM withholds information about condoms and contraception, promotes religious ideologies and gender stereotypes, and stigmatizes adolescents with nonheteronormative sexual identities [ 7 – 9 , 11 – 13 ]. Other federal funding priorities have moved positively toward more medically accurate and evidence-based programs, including teen pregnancy prevention programs [ 1 , 3 , 12 ]. These programs, although an improvement from AOUM, are not without their challenges though, as they currently operate within a relatively narrow, restrictive scope of “evidence” [ 12 ].

At the state level, individual states, districts, and school boards determine implementation of federal policies and funds. Limited in-class time and resources leave schools to prioritize sex education in competition with academic subjects and other important health topics such as substance use, bullying, and suicide [ 4 , 13 , 14 ]. Without cohesive or consistent implementation processes, a highly diverse “patchwork” of sex education laws and practices exists [ 4 ]. A recent report by the Guttmacher Institute noted that although 37 states require abstinence information be provided (25 that it be stressed), only 33 and 18 require HIV and contraceptive information, respectively [ 1 ]. Regarding content, quality, and inclusivity, 13 states mandate instruction be medically accurate, 26 that it be age appropriate, eight that it not be race/ethnicity or gender bias, eight that it be inclusive of sexual orientation, and two that it not promote religion [ 1 ]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2014 School Health Policies and Practices Study found that high school courses require, on average, 6.2 total hours of instruction on human sexuality, with 4 hours or less on HIV, other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and pregnancy prevention [ 15 ]. Moreover, 69% of high schools notify parents/guardians before students receive such instruction; 87% allow parents/guardians to exclude their children from it [ 15 ]. Without coordinated plans for implementation, credible guidelines, standards, or curricula, appropriate resources, supportive environments, teacher training, and accountability, it is no wonder that state practices are so disparate [ 4 ].

At the societal level, deeply rooted cultural and religious norms around adolescent sexuality have shaped federal and state policies and practices, driving restrictions on comprehensive sexual and reproductive health information, and service delivery in schools and elsewhere [ 12 , 13 ]. Continued public and political debates on the morality of sex outside marriage perpetuate barriers at multiple levels—by misguiding state funding decisions, molding parents’ (mis)understanding of programs, facilitating adolescents’ uptake of biased and inaccurate information in the classroom, and/or preventing their participation in sex education altogether [ 4 , 7 , 8 , 12 – 14 ].

Trends in Adolescents’ Receipt of Sex Education

In this month’s Journal of Adolescent Health , Lindberg et al. [ 16 ] provide further insight into the current state of sex education and the implications of federal and state policies for adolescents in the United States. Using population data from the National Survey of Family Growth, they find reductions in U.S. adolescents’ receipt of formal sex education from schools and other community institutions between 2006–2010 and 2011–2013. These declines continue previous trends from 1995–2002 to 2006–2008, which included increases in receipt of abstinence information and decreases in receipt of birth control information [ 17 – 19 ]. Moreover, the study highlights several additional new concerns. First, important inequities have emerged, the most significant of which are greater declines among girls than boys, rural-urban disparities, declines concentrated among white girls, and low rates among poor adolescents. Second, critical gaps exist in the types of information (practical types on “where to get birth control” and “how to use condoms” were lowest) and the mistiming of information (most adolescents received instruction after sexual debut) received. Finally, although receipt of sex education from parents appears to be stable, rates are low, such that parental-provided information cannot be adequately compensating for gaps in formal instruction.

Paradoxically, the declines in formal sex education from 2006 to 2013 have coincided with sizeable declines in adolescent birth rates and improved rates of contraceptive method use in the United States from 2007 to 2014 [ 20 , 21 ]. These coincident trends suggest that adolescents are receiving information about birth control and condoms elsewhere. Although the National Survey of Family Growth does not provide data on Internet use, Lindberg et al. [ 16 ] suggest that it is likely an important new venue for sex education. Others have commented on the myriad of online sexual and reproductive resources available to adolescents and their increasing use of sites such as Bedsider.org, StayTeen.org, and Scarleteen. [ 2 , 14 , 22 – 24 ].

The Future of Sex Education

Given the insufficient state of sex education in the United States in 2016, existing gaps are opportunities for more ambitious, forward-thinking strategies that cross-cut levels to translate an expanded evidence base into best practices and policies. Clearly, digital and social media are already playing critical roles at the societal level and can serve as platforms for disseminating innovative, scientifically and medically sound models of sex education to diverse groups of adolescents, including sexual minority adolescents [ 14 , 22 – 24 ]. Research, program, and policy efforts are urgently needed to identify effective ways to harness media within classroom, clinic, family household, and community contexts to reach the range of key stakeholders [ 13 , 14 , 22 – 24 ]. As adolescents turn increasingly to the Internet for their sex education, perhaps school-based settings can better serve other unmet needs, such as for comprehensive sexual and reproductive health care, including the full range of contraceptive methods and STI testing and treatment services. [ 15 , 25 ].

At the policy level, President Obama’s budget for FY 2017 reflects a strong commitment to supporting youths’ access to age-appropriate, medically accurate sexual health information, with proposed elimination of AOUM and increased investments in more comprehensive programs [ 3 ]. Whether these priorities will survive an election year and new administration is uncertain. It will also be important to monitor the impact of other health policies, particularly regarding contraception and abortion, which have direct and indirect implications for minors’ rights and access to sexual and reproductive health information and care [ 26 ].

At the state and local program level, models of sex education that are grounded in a broader interdisciplinary body of evidence are warranted [ 4 , 11 – 14 , 27 – 29 ]. The most exciting studies have found programs with rights-based content, positive, youth-centered messages, and use of interactive, participatory learning and skill building are effective in empowering adolescents with the knowledge and tools required for healthy sexual decision-making and behaviors [ 4 , 11 – 14 , 27 – 29 ]. Modern implementation strategies must use complementary modes of communication and delivery, including peers, digital and social media, and gaming, to fully engage young people [ 14 , 22 , 23 , 27 ].

Ultimately, expanded, integrated, multilevel approaches that reach beyond the classroom and capitalize on cutting-edge, youth-friendly technologies are warranted to shift cultural paradigms of sexual health, advance the state of sex education, and improve sexual and reproductive health outcomes for adolescents in the United States.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

K.S.H. is supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development #1K01HD080722-01A1.

Contributor Information

Kelli Stidham Hall, Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia.

Jessica McDermott Sales, Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia.

Kelli A. Komro, Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia.

John Santelli, Department of Population & Family Health, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, New York.

Why do we have single sex schools? What’s the history behind one of the biggest debates in education?

Lecturer in Gender and Cultural Studies, University of Sydney

Professor, University of Sydney

Senior Lecturer in Health Education, University of Sydney

Disclosure statement

Jessica Kean receives funding from an Australian Research Council Special Research Initiative grant 'Australian Boys: Beyond the Boy Problem'.

Helen Proctor receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Kellie Burns previously received funding from the University of Sydney, Equity Prize.

University of Sydney provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

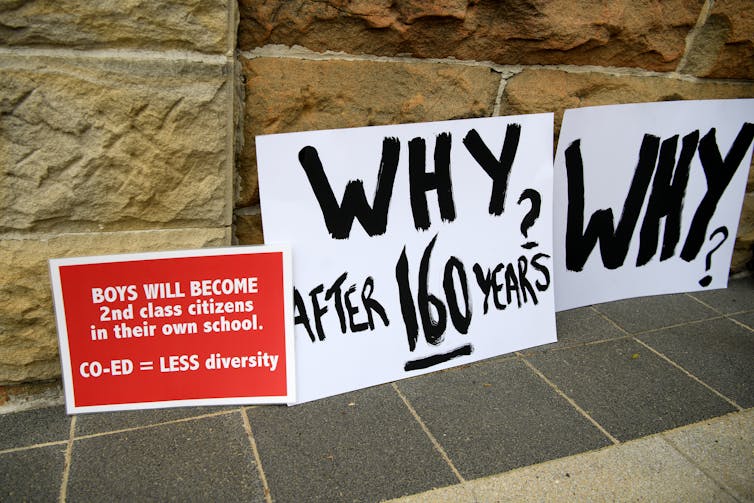

When students walked through the sandstone gates of Sydney’s Newington College for the first day of school last week, they were met by protesters .

A group of parents and former students had gathered outside this prestigious school in the city’s inner west, holding placards decrying the school’s decision to become fully co-educational by 2033.

Protesters have even threatened legal action to defend the 160-year-old tradition of boys’ education at the school. One told Channel 9 they fear the change is driven by “woke […] palaver” that will disadvantage boys at Newington.

Newington is not the only prestigious boys school to open enrolments to girls. Cranbrook in Sydney’s east will also go fully co-ed, with the decision sparking a heated community debate .

This debate is not a new one. What is the history behind the single-sex vs co-ed divide? And why does it spark so much emotion?

Read more: As another elite boys' school goes co-ed, are single-sex schools becoming an endangered species?

What is the history of the debate?

Schools like Newington were set up at a time when the curriculum and social worlds for upper-class boys and girls were often quite different. Boys and girls were thought to require different forms of education for their intellectual and moral development.

The question of whether it’s a good idea to educate boys and girls separately has been debated in Australia for at least 160 years, around the time Newington was set up.

In the 1860s, the colony of Victoria introduced a policy of coeducation for all government-run schools. This was despite community concerns about “ moral well-being ”. There was a concern that boys would be a “corrupting influence” on the girls. So schools were often organised to minimise contact between boys and girls even when they shared a classroom.

Other colonies followed suit. The main reason the various Australian governments decided to educate boys and girls together was financial. It was always cheaper, especially in regional and rural areas, to build one school than two. So most government schools across Australia were established to enrol both girls and boys.

One notable exception was New South Wales, which set up a handful of single-sex public high schools in the 1880s.

These were intended to provide an alternative to single-sex private secondary schools. At that time, education authorities did not believe parents would agree to enrol their children in mixed high schools. Historically, coeducation has been more controversial for older students, but less so for students in their primary years.

A changing debate

By the 1950s, many education experts were arguing coeducation was better for social development than single-sex schooling. This was at a time of national expansion of secondary schooling in Australia and new psychological theories about adolescents.

In following decades, further debates emerged. A feminist reassessment in the 1980s argued girls were sidelined in co-ed classes. This view was in turn challenged during the 1990s , with claims girls were outstripping boys academically and boys were being left behind in co-ed environments.

Which system delivers better academic results?

There is no conclusive evidence that one type of schooling (co-ed or single sex) yields better academic outcomes than the other.

Schools are complex and diverse settings. There are too many variables (such as resourcing, organisational structures and teaching styles) to make definitive claims about any one factor. Many debates about single-sex vs co-ed schooling also neglect social class as a key factor in academic achievement.

What about the social environment?

Research about the social outcomes of co-ed vs single-sex schools is also contested.

Some argue co-ed schooling better prepares young people for the co-ed world they will grow up in.

Others have suggested boys may fare better in co-ed settings, with girls acting as a counterbalance to boys’ unruliness. But it has also been argued boys take up more space and teacher time, detracting from girls’ learning and confidence.

Both of these arguments rely on gender stereotypes about girls being compliant and timid and boys being boisterous and disruptive.

Key to these debates is a persistent belief that girls and boys learn differently. These claims do not have a strong basis in educational research.

Read more: We can see the gender bias of all-boys' schools by the books they study in English

Why such a heated debate?

Tradition plays a big part in this debate. Often, parents want their children to have a similar schooling experience to themselves.

For others it’s about access to specific resources and experiences. Elite boys schools have spent generations accumulating social and physical resources tailored to what they believe boys are interested in and what they believe is in boys’ best interests . This includes sports facilities, curriculum offerings, approaches to behaviour management and “old boys” networks.

Many of these schools have spent decades marketing themselves as uniquely qualified to educate boys (or a certain type of boy). So it’s not surprising if some in these school communities are resisting change.

More concerning are the Newington protesters who suggest this move toward inclusivity and gender diversity will make boys “second-class citizens”. This echoes a refrain common in anti-feminist and anti-trans backlash movements , which position men and boys as vulnerable in a world of changing gender norms. This overlooks the ways they too can benefit from the embrace of greater diversity at school.

As schools do the work to open up to more genders , it is likely they will also become welcoming to a wider range of boys and young men.

- Private schools

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

Partner, Senior Talent Acquisition

Deputy Editor - Technology

Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Academic and Student Life)

- Education Lab

- Local Politics

What to know about WA’s law requiring LGBTQ+ history in public schools

Public schools in Washington will be required to teach students about the contributions and history of LGBTQ+ people under a new law signed by Gov. Jay Inslee on Monday.

Senate Bill 5462 mandates that school districts in Washington adopt curricula that include “diverse, equitable, inclusive, age-appropriate instructional materials” that reflect the history and perspectives of historically underrepresented groups.

State learning standards already direct schools to teach students about the historical perspectives of some marginalized groups, such as tribal communities and enslaved people, but did not explicitly require lessons covering LGBTQ+ histories.

“The contributions of gay Washingtonians deserve recognition, and just as importantly, students deserve to see themselves in their schoolwork,” Sen. Marko Liias, a Democrat from Edmonds who sponsored the bill, said in a statement. “That leads to better attendance, better academic achievement and better overall quality of life, ensuring success for all our students.”

Washington joins six other states — California, Colorado, Illinois, Nevada, New Jersey and Oregon — that have similar requirements for academic curricula to include representation of LGBTQ+ people in public schools.

Wave of bans

The new law comes at a time when school boards and libraries across the country have faced a wave of Republican-led book and curriculum bans on content related to LGBTQ+ people and people of color.

“Right now, with the attacks from the extreme right, we’re finding LGBTQ people, especially youth, are feeling unsafe,” said Jaelynn Scott, executive director of the Lavender Rights Project, a Seattle-based LGBTQ+ legal advocacy organization.

“It’s important Washington state shows itself as a leader affirming inclusive curriculum for students,” Scott said.

The bill passed in both chambers without any Republican support. Opponents had argued the bill infringes on the rights of parents and powers of local school districts to decide what their kids learn in the classroom.

Benefits of education

In schools where students learned about LGBTQ+ people, history and events, LGBTQ+ students were less likely to hear homophobic or transphobic remarks and less likely to miss school because they felt unsafe, according to a 2021 national survey from GLSEN , an LGBTQ+ education advocacy group. Those students also had better mental health and academic performance, the survey found.

Additionally, LGBTQ+ middle and high school students who learned about LGBTQ+ history or people in class reported lower rates of suicide attempts in the last year, according to a 2023 study from the Trevor Project, a suicide prevention organization for LGBTQ+ youth.

“A positive school environment [has] a large impact on the health and well-being of students, even more so than work and home environments,” Scott said.

How the law will take effect

Under the law, the Washington State School Directors’ Association, with assistance from the state Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, will create a model policy and procedure on how to design courses and select instructional materials by June 2025. Then, by October of that year, schools will have to update their policies to incorporate the new curricula.

In other states with inclusive curricula on LGBTQ+ history, schools teach about landmark Supreme Court cases, like Obergefell v. Hodges , which guaranteed a right to same-sex marriage in 2015, or how LGBTQ+ subcultures became more visible and accepted during the Prohibition era. Editor’s note: The comment thread on this story has been closed because too many recent comments were violating our Code of Conduct .

Most Read Stories

- FBI to Alaska Airlines Flight 1282 passengers: You may be a crime victim

- 10 Washington road-trip spots recommended by the people who know them best

- Kate, Princess of Wales, reveals she has cancer and is undergoing chemotherapy WATCH

- Woman killed in Renton crash remembered as loving mother, educator

- Russia says 60 dead, 145 injured in concert hall raid; Islamic State group claims responsibility WATCH

Current Weather

Mount pleasant.

Latest Weathercast

Interactive Radar

Washington governor signs bill requiring schools to teach LGBTQ+ history starting in 2025

by KOMO News Staff

SEATTLE (KOMO) — There's a new curriculum coming to Washington’s public schools starting in the 2025-2026 school year.

Senate Bill 5462, which Gov. Jay Inslee signed into law this week, will mandate students to learn about the contributions of underrepresented groups in school, including those in the LGBTQ+ community.

SB 5462 was introduced in January and went through multiple committee meetings, public hearings and revisions - more than a dozen – during the Legislative session. Many residents may not have realized what the bill calls for because LGBTQ is not in the language of the bill.

Now that the bill has been signed into law, it directs the state to create a curriculum that highlights the many contributions people of different races, ethnicities and even sexual orientations have made.

"I don’t believe that’s the state’s responsibility. When you break down our main reason for being opposed to more or less the sexualization of children at that very young age," Brian Noble, with the Family Policy Institute of Washington, told KOMO News.

Danni Askini, with the Gender Justice League, gave KOMO News a different perspective.

“I think that this is based on a stereotype. And I think that even mentioning that LGBTQ+ people are sexual is like mentioning mothers get pregnant and have babies that are somehow sexual. It’s not inherently sexual. It’s a fact of life. Acknowledging the existence of LGBT people does not inherently sexualize anybody, and it does not promote sexual behavior,” said Askini.

The Washington Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) must now create a curriculum that addresses not only those contributions, but also the history and perspectives of those groups.

“I have no problem with us informing about cultures about different areas like that,” said Brian Noble with the Family Policy Institute of Washington. “But when it comes to our sexual behavior, those histories and what we’re heightening as acceptable, and as normal, I do believe the conversation should happen between the child and their parent or parents.”

Noble told KOMO News that while raising his children, he had very different conversations with them at age 17 versus age 18 and believes the lessons in the new law should not happen with minors in the Washington state public school system but instead with adults in the family's home.

Askini agrees that parents have an essential role in educating young people but also points out that there are tens of thousands of students who have LGBTQ+ parents in Washington.

“Those parents should be reflected in the curriculum in our community, which is about, you know, seven to 10% of the population. We should be able to see ourselves reflected in the educational environment that our children, both LGBT and children who have LGBT parents. I think it is from this idea that somehow LGBT people are outside or separate from the community. It’s just absolutely false,” said Askini.

"This bill, forcing curriculum selection that would praise and highlight gay pride activists or gender-confused individuals, will only drive more parents away as our public education system seeks to promote agendas over public education,” said Gary Wilson during a public hearing in Olympia.

Sen. Marko Liias , the bill’s sponsor, argued the contributions of gay Washingtonians deserve recognition. He also said students who see themselves in their schoolwork miss fewer days of school and perform better academically.

The OSPI and the Washington State School Directors' Association are to create the new curricula by the end of the next school year that will be taught starting with the 2025-2026 school year.

“I think that we should pump the brakes. The fact is we just need to get back to reading, writing, and arithmetic,” said Noble.

But Askini circled back to studies that show kids who see others like themselves have better attendance and higher achievements.

“Acknowledging the facts of our community, the reality of the world that we live in, and the people that are in that world is not the same as encouraging any type of one type of behavior or one belief,” said Askini.

A committee will be formed to help create the curricula that will include parents, but parents can only make up less than 50% of that committee.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

The first wave of organized opposition, from the late 1960s to the early 1980s, took the form of attacks aimed at barring any form of sex ed in school. Sex education programs were described by the Christian Crusade and other conservative groups as "smut" and "raw sex.". The John Birch Society termed the effort to teach about sexuality ...

in the 1980s, a debate began in the United States between a more comprehensive approach to sex education, which provided information about sexual health — including information about contraception — and abstinence only programs. Education about sex and sexualtiy in U.S. schools progressed in these two divergent directions. The former was based

We provide a historical perspective toward the current public school practices of American sex education. The primary time frames include the progressive era (1880-1920), intermediate era (1920-1960), the sexual revolution era (1960s and 1970s), and the modern sex education era (1980s to the present).

"The History of Teaching and Talking about Sex in Schools." History of Education Quarterly, edited by Jeffrey P. Moran and Janice M. Irvine, vol. 43, no. 4, 2003, pp. 610-15. JSTOR. Burnham, John C. "The Progressive Era Revolution in American Attitudes Toward Sex."

How AIDS Changed the History of Sex Education. 4 minute read. A Denver Public School sex education class in 1971 Barry Staver—Denver Post Archive / Getty Images. By Lily Rothman.

history of sex education in United States public schools, a previously under-researched area. These two works, in turn, provide important groundwork on which a rich variety of scholarship in the history of education may yet be written. The first of these volumes, Jeffrey Moran's Teaching Sex: The Shap-

How did sex education evolve in the United States? What are the historical, social, and political factors that shaped its development? This pdf document from SIECUS, a leading organization for sex ed for social change, provides a comprehensive overview of the history of sex education from the 19th century to the present. Learn about the milestones, challenges, and controversies that have ...

HISTORY OF SEX EDUCATION IN THE U.S. The primary goal of sexuality education is the promotion of sexual health (NGTF, 1996). In 1975, the World Health Organization offered this definition of sexual health: Sexual health is the integration of the somatic, emotional, intellectual, and social aspects of sexual being, in ways that are positively ...

Sex education was largely seen as teaching about reproduction and so undertaken in biology lessons. Biology was widely perceived as a more suitable subject for girls than for boys, and girls were more likely than boys to receive school sex education. The 1970s and 1980s. By the start of the 1970s, school sex education was beginning to change ...

Launched in March in honor of Women's History Month, the report surveys the history of sex education from the early 20th century to the present. Founded by Dr. Mary S. Calderone in 1964, SIECUS has worked to transform sex education into a critical tool for social justice. Their mission acknowledges "sex ed sits as the nexus of many social ...

The backlash against sex education in the schools kept pace with the backlash against integration, with each often used to bolster the other. Opponents of integration and sex education, for example, often used racial language to scare parents about what kids were learning, and with whom.In the 1980s and 1990s, the political power of the ...