Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples

Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples

Published on October 18, 2021 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Ethical considerations in research are a set of principles that guide your research designs and practices. Scientists and researchers must always adhere to a certain code of conduct when collecting data from people.

The goals of human research often include understanding real-life phenomena, studying effective treatments, investigating behaviors, and improving lives in other ways. What you decide to research and how you conduct that research involve key ethical considerations.

These considerations work to

- protect the rights of research participants

- enhance research validity

- maintain scientific or academic integrity

Table of contents

Why do research ethics matter, getting ethical approval for your study, types of ethical issues, voluntary participation, informed consent, confidentiality, potential for harm, results communication, examples of ethical failures, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research ethics.

Research ethics matter for scientific integrity, human rights and dignity, and collaboration between science and society. These principles make sure that participation in studies is voluntary, informed, and safe for research subjects.

You’ll balance pursuing important research objectives with using ethical research methods and procedures. It’s always necessary to prevent permanent or excessive harm to participants, whether inadvertent or not.

Defying research ethics will also lower the credibility of your research because it’s hard for others to trust your data if your methods are morally questionable.

Even if a research idea is valuable to society, it doesn’t justify violating the human rights or dignity of your study participants.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Before you start any study involving data collection with people, you’ll submit your research proposal to an institutional review board (IRB) .

An IRB is a committee that checks whether your research aims and research design are ethically acceptable and follow your institution’s code of conduct. They check that your research materials and procedures are up to code.

If successful, you’ll receive IRB approval, and you can begin collecting data according to the approved procedures. If you want to make any changes to your procedures or materials, you’ll need to submit a modification application to the IRB for approval.

If unsuccessful, you may be asked to re-submit with modifications or your research proposal may receive a rejection. To get IRB approval, it’s important to explicitly note how you’ll tackle each of the ethical issues that may arise in your study.

There are several ethical issues you should always pay attention to in your research design, and these issues can overlap with each other.

You’ll usually outline ways you’ll deal with each issue in your research proposal if you plan to collect data from participants.

Voluntary participation means that all research subjects are free to choose to participate without any pressure or coercion.

All participants are able to withdraw from, or leave, the study at any point without feeling an obligation to continue. Your participants don’t need to provide a reason for leaving the study.

It’s important to make it clear to participants that there are no negative consequences or repercussions to their refusal to participate. After all, they’re taking the time to help you in the research process , so you should respect their decisions without trying to change their minds.

Voluntary participation is an ethical principle protected by international law and many scientific codes of conduct.

Take special care to ensure there’s no pressure on participants when you’re working with vulnerable groups of people who may find it hard to stop the study even when they want to.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Informed consent refers to a situation in which all potential participants receive and understand all the information they need to decide whether they want to participate. This includes information about the study’s benefits, risks, funding, and institutional approval.

You make sure to provide all potential participants with all the relevant information about

- what the study is about

- the risks and benefits of taking part

- how long the study will take

- your supervisor’s contact information and the institution’s approval number

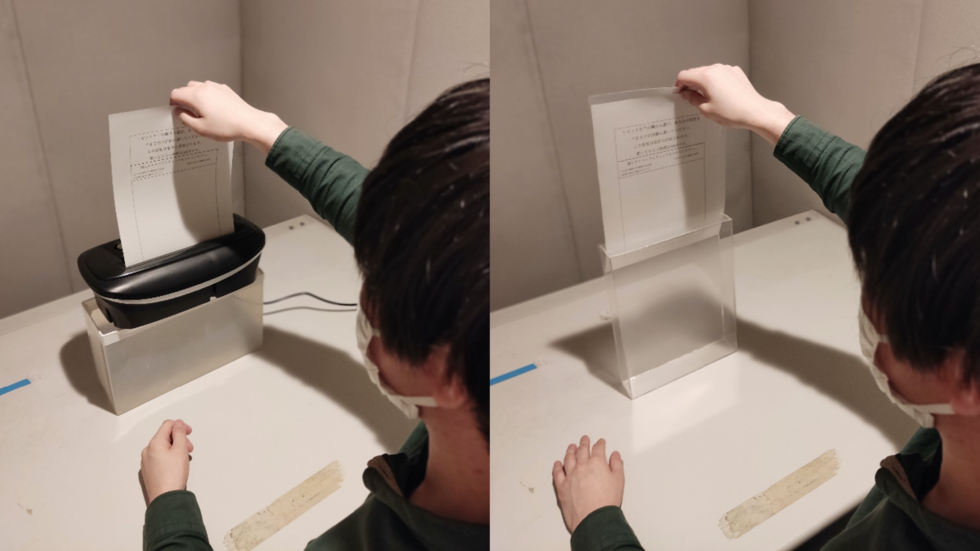

Usually, you’ll provide participants with a text for them to read and ask them if they have any questions. If they agree to participate, they can sign or initial the consent form. Note that this may not be sufficient for informed consent when you work with particularly vulnerable groups of people.

If you’re collecting data from people with low literacy, make sure to verbally explain the consent form to them before they agree to participate.

For participants with very limited English proficiency, you should always translate the study materials or work with an interpreter so they have all the information in their first language.

In research with children, you’ll often need informed permission for their participation from their parents or guardians. Although children cannot give informed consent, it’s best to also ask for their assent (agreement) to participate, depending on their age and maturity level.

Anonymity means that you don’t know who the participants are and you can’t link any individual participant to their data.

You can only guarantee anonymity by not collecting any personally identifying information—for example, names, phone numbers, email addresses, IP addresses, physical characteristics, photos, and videos.

In many cases, it may be impossible to truly anonymize data collection . For example, data collected in person or by phone cannot be considered fully anonymous because some personal identifiers (demographic information or phone numbers) are impossible to hide.

You’ll also need to collect some identifying information if you give your participants the option to withdraw their data at a later stage.

Data pseudonymization is an alternative method where you replace identifying information about participants with pseudonymous, or fake, identifiers. The data can still be linked to participants but it’s harder to do so because you separate personal information from the study data.

Confidentiality means that you know who the participants are, but you remove all identifying information from your report.

All participants have a right to privacy, so you should protect their personal data for as long as you store or use it. Even when you can’t collect data anonymously, you should secure confidentiality whenever you can.

Some research designs aren’t conducive to confidentiality, but it’s important to make all attempts and inform participants of the risks involved.

As a researcher, you have to consider all possible sources of harm to participants. Harm can come in many different forms.

- Psychological harm: Sensitive questions or tasks may trigger negative emotions such as shame or anxiety.

- Social harm: Participation can involve social risks, public embarrassment, or stigma.

- Physical harm: Pain or injury can result from the study procedures.

- Legal harm: Reporting sensitive data could lead to legal risks or a breach of privacy.

It’s best to consider every possible source of harm in your study as well as concrete ways to mitigate them. Involve your supervisor to discuss steps for harm reduction.

Make sure to disclose all possible risks of harm to participants before the study to get informed consent. If there is a risk of harm, prepare to provide participants with resources or counseling or medical services if needed.

Some of these questions may bring up negative emotions, so you inform participants about the sensitive nature of the survey and assure them that their responses will be confidential.

The way you communicate your research results can sometimes involve ethical issues. Good science communication is honest, reliable, and credible. It’s best to make your results as transparent as possible.

Take steps to actively avoid plagiarism and research misconduct wherever possible.

Plagiarism means submitting others’ works as your own. Although it can be unintentional, copying someone else’s work without proper credit amounts to stealing. It’s an ethical problem in research communication because you may benefit by harming other researchers.

Self-plagiarism is when you republish or re-submit parts of your own papers or reports without properly citing your original work.

This is problematic because you may benefit from presenting your ideas as new and original even though they’ve already been published elsewhere in the past. You may also be infringing on your previous publisher’s copyright, violating an ethical code, or wasting time and resources by doing so.

In extreme cases of self-plagiarism, entire datasets or papers are sometimes duplicated. These are major ethical violations because they can skew research findings if taken as original data.

You notice that two published studies have similar characteristics even though they are from different years. Their sample sizes, locations, treatments, and results are highly similar, and the studies share one author in common.

Research misconduct

Research misconduct means making up or falsifying data, manipulating data analyses, or misrepresenting results in research reports. It’s a form of academic fraud.

These actions are committed intentionally and can have serious consequences; research misconduct is not a simple mistake or a point of disagreement about data analyses.

Research misconduct is a serious ethical issue because it can undermine academic integrity and institutional credibility. It leads to a waste of funding and resources that could have been used for alternative research.

Later investigations revealed that they fabricated and manipulated their data to show a nonexistent link between vaccines and autism. Wakefield also neglected to disclose important conflicts of interest, and his medical license was taken away.

This fraudulent work sparked vaccine hesitancy among parents and caregivers. The rate of MMR vaccinations in children fell sharply, and measles outbreaks became more common due to a lack of herd immunity.

Research scandals with ethical failures are littered throughout history, but some took place not that long ago.

Some scientists in positions of power have historically mistreated or even abused research participants to investigate research problems at any cost. These participants were prisoners, under their care, or otherwise trusted them to treat them with dignity.

To demonstrate the importance of research ethics, we’ll briefly review two research studies that violated human rights in modern history.

These experiments were inhumane and resulted in trauma, permanent disabilities, or death in many cases.

After some Nazi doctors were put on trial for their crimes, the Nuremberg Code of research ethics for human experimentation was developed in 1947 to establish a new standard for human experimentation in medical research.

In reality, the actual goal was to study the effects of the disease when left untreated, and the researchers never informed participants about their diagnoses or the research aims.

Although participants experienced severe health problems, including blindness and other complications, the researchers only pretended to provide medical care.

When treatment became possible in 1943, 11 years after the study began, none of the participants were offered it, despite their health conditions and high risk of death.

Ethical failures like these resulted in severe harm to participants, wasted resources, and lower trust in science and scientists. This is why all research institutions have strict ethical guidelines for performing research.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Thematic analysis

- Cohort study

- Peer review

- Ethnography

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Conformity bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Availability heuristic

- Attrition bias

- Social desirability bias

Ethical considerations in research are a set of principles that guide your research designs and practices. These principles include voluntary participation, informed consent, anonymity, confidentiality, potential for harm, and results communication.

Scientists and researchers must always adhere to a certain code of conduct when collecting data from others .

These considerations protect the rights of research participants, enhance research validity , and maintain scientific integrity.

Research ethics matter for scientific integrity, human rights and dignity, and collaboration between science and society. These principles make sure that participation in studies is voluntary, informed, and safe.

Anonymity means you don’t know who the participants are, while confidentiality means you know who they are but remove identifying information from your research report. Both are important ethical considerations .

You can only guarantee anonymity by not collecting any personally identifying information—for example, names, phone numbers, email addresses, IP addresses, physical characteristics, photos, or videos.

You can keep data confidential by using aggregate information in your research report, so that you only refer to groups of participants rather than individuals.

These actions are committed intentionally and can have serious consequences; research misconduct is not a simple mistake or a point of disagreement but a serious ethical failure.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 10, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/research-ethics/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, data collection | definition, methods & examples, what is self-plagiarism | definition & how to avoid it, how to avoid plagiarism | tips on citing sources, what is your plagiarism score.

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

Understanding Scientific and Research Ethics

How to pass journal ethics checks to ensure a smooth submission and publication process

Reputable journals screen for ethics at submission—and inability to pass ethics checks is one of the most common reasons for rejection. Unfortunately, once a study has begun, it’s often too late to secure the requisite ethical reviews and clearances. Learn how to prepare for publication success by ensuring your study meets all ethical requirements before work begins.

The underlying principles of scientific and research ethics

Scientific and research ethics exist to safeguard human rights, ensure that we treat animals respectfully and humanely, and protect the natural environment.

The specific details may vary widely depending on the type of research you’re conducting, but there are clear themes running through all research and reporting ethical requirements:

Documented 3rd party oversight

- Consent and anonymity

- Full transparency

If you fulfill each of these broad requirements, your manuscript should sail through any journal’s ethics check.

If your research is 100% theoretical, you might be able to skip this one. But if you work with living organisms in any capacity—whether you’re administering a survey, collecting data from medical records, culturing cells, working with zebrafish, or counting plant species in a ring—oversight and approval by an ethics committee is a prerequisite for publication. This oversight can take many different forms:

For human studies and studies using human tissue or cells, obtain approval from your institutional review board (IRB). Register clinical trials with the World Health Organization (WHO) or International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE). For animal research consult with your institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC). Note that there may be special requirements for non-human primates, cephalopods, and other specific species, as well as for wild animals. For field studies , anthropology and paleontology , the type of permission required will depend on many factors, like the location of the study, whether the site is publicly or privately owned, possible impacts on endangered or protected species, and local permit requirements.

TIP: You’re not exempt until your committee tells you so

Even if you think your study probably doesn’t require approval, submit it to the review board anyway. Many journals won’t consider retrospective approvals. Obtaining formal approval or an exemption up front is worth it to ensure your research is eligible for publication in the future.

TIP: Keep your committee records close

Clearly label your IRB/IACUC paperwork, permit numbers, and any participant permission forms (including blank copies), and keep them in a safe place. You will need them when you submit to a journal. Providing these details proactively as part of your initial submission can minimize delays and get your manuscript through journal checks and into the hands of reviewers sooner.

Consent & anonymity

Obtaining consent from human subjects.

You may not conduct research on human beings unless the subjects understand what you are doing and agree to be a part of your study. If you work with human subjects, you must obtain informed written consent from the participants or their legal guardians.

There are many circumstances where extra care may be required in order to obtain consent. The more vulnerable the population you are working with the stricter these guidelines will be. For example, your IRB may have special requirements for working with minors, the elderly, or developmentally delayed participants. Remember that these rules may vary from country to country. Providing a link to the relevant legal reference in your area can help speed the screening and approval process.

TIP: What if you are working with a population where reading and writing aren’t common?

Alternatives to written consent (such as verbal consent or a thumbprint) are acceptable in some cases, but consent still has to be clearly documented. To ensure eligibility for publication, be sure to:

- Get IRB approval for obtaining verbal rather than written consent

- Be prepared to explain why written consent could not be obtained

- Keep a copy of the script you used to obtain this consent, and record when consent was obtained for your own records

Consent and reporting for human tissue and cell lines

Consent from the participant or their next-of-kin is also required for the use of human tissue and cell lines. This includes discarded tissue, for example the by-products of surgery.

When working with cell lines transparency and good record keeping are essential. Here are some basic guidelines to bear in mind:

- When working with established cell lines , cite the published article where the cell line was first described.

- If you’re using repository or commercial cell lines , explain exactly which ones, and provide the catalog or repository number.

- If you received a cell line from a colleague , rather than directly from a repository or company, be sure to mention it. Explain who gifted the cells and when.

- For a new cell line obtained from a colleague there may not be a published article to cite yet, but the work to generate the cell line must meet the usual requirements of consent—even if it was carried out by another research group. You’ll need to provide a copy of your colleagues’ IRB approval and details about the consent procedures in order to publish the work.

Finally, you’re obliged to keep your human subjects anonymous and to protect any identifying information in photos and raw data. Remove all names, birth dates, detailed addresses, or job information from files you plan to share. Blur faces and tattoos in any images. Details such as geography (city/country), gender, age, or profession may be shared at a generalized level and in aggregate. Read more about standards for de-identifying datasets in The BMJ .

TIP: Anonymity can be important in field work too

Be careful about revealing geographic data in fieldwork. You don’t want to tip poachers off to the location of the endangered elephant population you studied, or expose petroglyphs to vandalism.

Full Transparency

No matter the discipline, transparent reporting of methods, results, data, software and code is essential to ethical research practice. Transparency is also key to the future reproducibility of your work.

When you submit your study to a journal, you’ll be asked to provide a variety of statements certifying that you’ve obtained the appropriate permissions and clearances, and explaining how you conducted the work. You may also be asked to provide supporting documentation, including field records and raw data. Provide as much detail as you can at this stage. Clear and complete disclosure statements will minimize back-and-forth with the journal, helping your submission to clear ethics checks and move on to the assessment stage sooner.

TIP: Save that data

As you work, be sure to clearly label and organize your data files in a way that will make sense to you later. As close as you are to the work as you conduct your study, remember that two years could easily pass between capturing your data and publishing an article reporting the results. You don’t want to be stuck piecing together confusing records in order to create figures and data files for repositories.

Read our full guide to preparing data for submission .

Keep in mind that scientific and research ethics are always evolving. As laws change and as we learn more about influence, implicit bias and animal sentience, the scientific community continues to strive to elevate our research practice.

A checklist to ensure you’re ethics-check ready

Before you begin your research

Obtain approval from your IRB, IACUC or other approving body

Obtain written informed consent from human participants, guardians or next-of-kin

Obtain permits or permission from property owners, or confirm that permits are not required

Label and save all of records

As you work

Adhere strictly to the protocols approved by your committee

Clearly label your data, and store it in a way that will make sense to your future self

As you write, submit and deposit your results

Be ready to cite specific approval organizations, permit numbers, cell lines, and other details in your ethics statement and in the methods section of your manuscript

Anonymize all participant data (including human and in some cases animal or geographic data)

If a figure does include identifying information (e.g. a participant’s face) obtain special consent

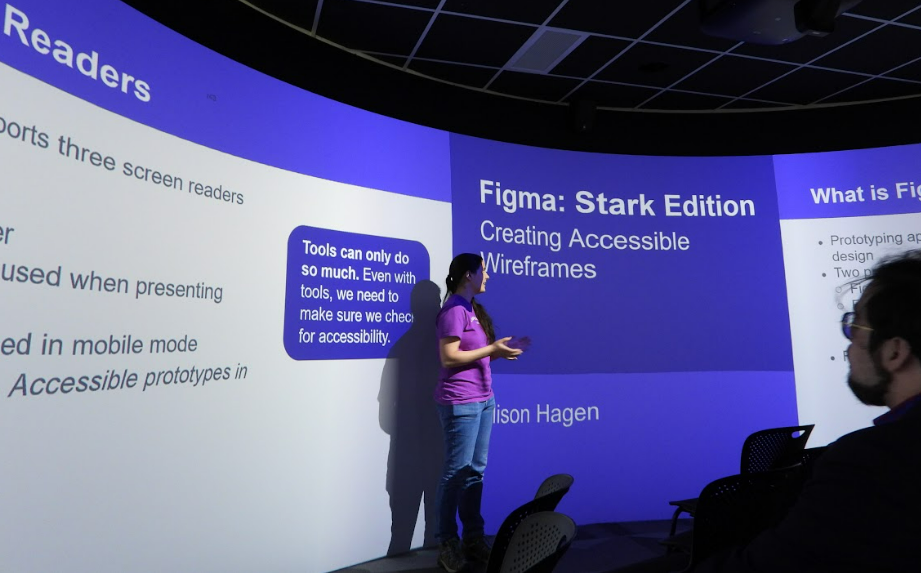

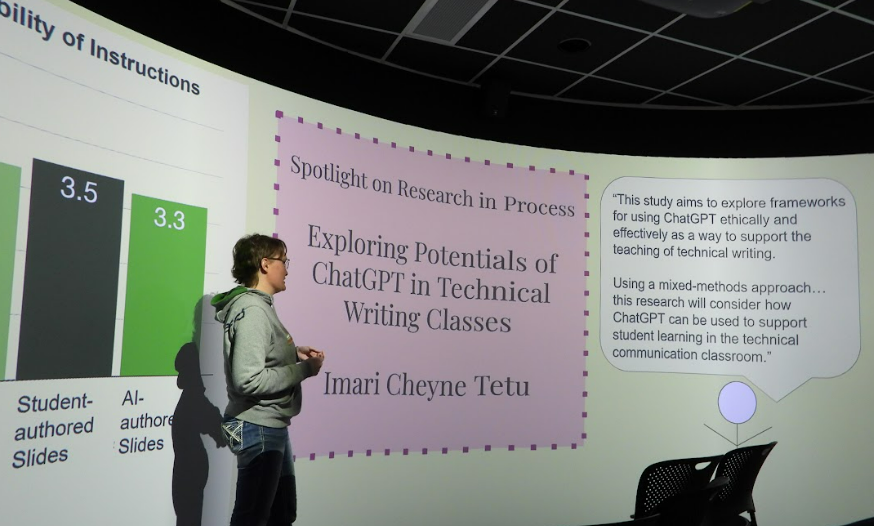

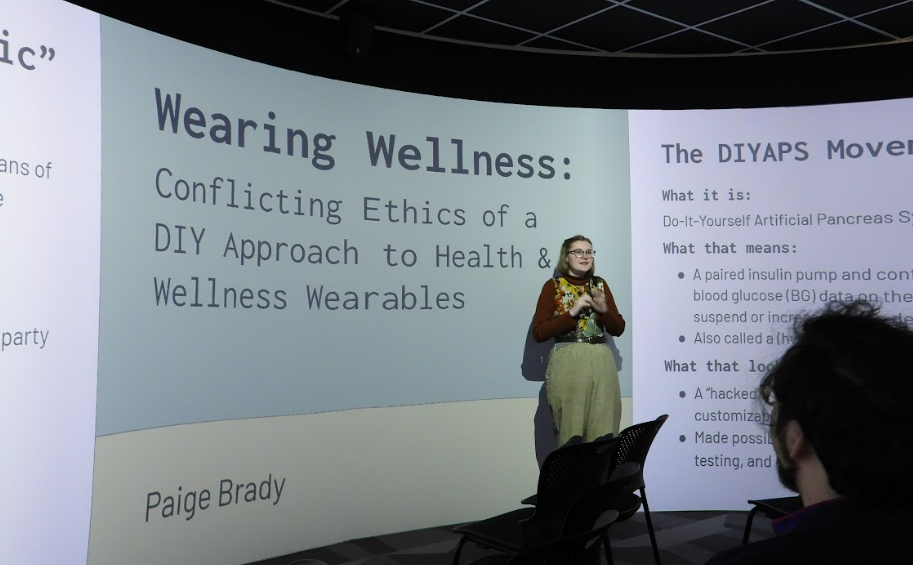

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

Table of Contents

Collaboration, information literacy, writing process, research ethics.

As an investigator be sure to protect your research subjects and follow ethical standards. As a consumer of research, be mindful of when investigators may be exaggerating results, making claims that exceed the authority of a research method, misrepresenting findings, or plagiarizing.

Research ethics are the moral principles and practices that guide how researchers work with information (especially data/texts), human subjects, and animals.

Since 1947, following the publication of the Nuremberg Code , governments (e.g., see Canada ) and professional organizations (e.g., see American Psychological Association) have created ethical codes of conduct to protect research subjects and society.

Since 1964, following the publication of the Declaration of Helsinki , investigators working with human subjects have been required to write an IRB Board in the U.S. or an Ethics Committee in the European Union before any research is conducted.

Research ethics and moral principles are a major concern across academic disciplines, professions, and consumers. Governments, hospitals, universities, and professional organizations have robust policies that guide how investigators work with texts, other humans, and animals, including

- policies for conducting research, such as prohibitions against plagiarism, misrepresentation of data, or fabrication of data

- policies for collaboration, authorship, peer review

- policies for protecting human subjects or animals involved in studies

- policies to account for, avoid, or ameliorate conflicts of interest

- policies for illustrating the value of funded research from governments, foundations, think tanks, and other organizations.

Even so, problems with research ethics endure.

Sometimes investigators cheat and engage in unethical behavior. Politics, economic interests, corporate interests, personal interests — these factors and more are associated with unethical behavior.

And sometimes investigators may not even be conscious that they are acting unethically. People can be unaware of their own confirmation bias, their tendency to ignore disconfirming evidence and selectively seek out evidence that confirms their thesis or research question .

Consumers of research are wise to consider ethics when weighing a study’s truth claims .

[ The CRAAP Test (Currency, Relevance, Authority, Accuracy, Purpose) ]

In 2009, Dr. Daniele Fanelli, a professor at The University of Edinburgh, conducted a meta analysis of 21 surveys that explored how frequently scientists fabricate, falsify or cook data. Remarkably, she discovered that 33.7% of the scientists surveyed admitted to questionable research practices. When discussing the work of colleagues they assumed 14.12% of scientists falsified data and 72% engaged in questionable research practices:

it is likely that, if on average 2% of scientists admit to have falsified research at least once and up to 34% admit other questionable research practices, the actual frequencies of misconduct could be higher than this. Fanelli, Daniele (5/29/09). How Many Scientists Fabricate and Falsify Research? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Survey Data . PLOS ONE, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0005738

For researchers, research ethics and moral principles are not an ornamental feature, an afterthought. Rather, ethical considerations form the foundation of research protocols , guiding the selection of research methods, the techniques used to gather and interpret data, and the ways data are interpreted and represented in research reports.

Examples of Research Ethics

To learn more about research ethics and moral principles, review the following ethical codes:

- National Science Foundation (NSF)

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

- US Department of Agriculture (USDA)

- Singapore Statement on Research Integrity

- American Chemical Society, The Chemist Professional’s Code of Conduct

- Code of Ethics (American Society for Clinical Laboratory Science)

- American Psychological Association, Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct

- Statement on Professional Ethics (American Association of University Professors)

- World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki

- International ethical guidelines for biomedical research involving human subjects

- International ethical guidelines for epidemiological studies

- European Group on Ethics

- Directive 2001/20/ec of the European Parliament and of the Council

- Council of Europe (Oviedo Convention – Protocol on biomedical research)

- National Institutes of Health (NIH)

Fanelli, Daniele (5/29/09). How Many Scientists Fabricate and Falsify Research? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Survey Data . PLOS ONE, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0005738

Related Articles:

Human subjects research, informed consent, irb (institutional review board), ethics committee, suggested edits.

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Be aware of the moral principles and practices that inform research with human subjects.

Informed Consent is a legal and ethical requirement for research studies engaged in human subjects research.

Prior to conducting research involving human subjects, be sure to seek approval from an IRB (Institional Review Board) or Ethics Committee.

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Authority – How to Establish Credibility in Speech & Writing

Ethics of Scientific Writing

- First Online: 21 March 2019

Cite this chapter

- Michael Hanna 2

2473 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Scientific writing is the process of putting information and thinking into a final permanent report, so it can be read and used by other people. For any given research study, there are innumerable various ways to legitimately write that report (depending on what exactly the authors want to say and how). But readers expect that each journal paper corresponds appropriately to the research reported. The amount of writing published about a research study should correspond appropriately to the amount and value of the actual research performed, and the writing about that research should be original, scientific, and truthful. Ethical problems arise whenever there is a gross disconnection between the writing activity of the authors and the actual research they have done. So ethical scientific writing involves several issues: 1) avoiding plagiarism – the copying of someone else’s expressions or ideas, 2) writing a report that is accurate and unbiased, 3) maintaining patient confidentiality, 4) not writing too many papers from a research study – so-called “salami publication”, and 5) not failing to actually write-up and publish a peer-reviewed journal paper about a completed study.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Office of Research Integrity – Office of Public Health and Science – U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Managing Allegations of Scientific Misconduct: A Guidance Document for Editors. Rockville, MD, USA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. Accessed on 24 October 2017 at: https://ori.hhs.gov/images/ddblock/masm_2000.pdf

ALLEA – All European Academies. The European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity, Revised Edition. Berlin: ALLEA; 2017. Accessed on 5 November 2017 at: www.allea.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/ALLEA-European-Code-of-Conduct-for-Research-Integrity-2017.pdf

Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, Global Science Forum. Best Practices for Ensuring Scientific Integrity and Preventing Misconduct. Accessed on 13 January 2018 at: www.oecd.org/science/inno/40188303.pdf

Fanelli D. How Many Scientists Fabricate and Falsify Research? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Survey Data. PLoS One. 2009; 4: e5738.

Article Google Scholar

Council of Science Editors. CSE’s White Paper on Promoting Integrity in Scientific Journal Publications, 2012 Update, 3rd Revised Edition. Wheat Ridge, CO: Council of Scientific Editors; 2012.

Google Scholar

Smith R. Time to face up to research misconduct. BMJ. 1996; 312: 789-790.

Article CAS Google Scholar

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals. Philadelphia: American College of Physicians; 1978, 2017. Accessed on 12 January 2018 at: www.icmje.org/icmje-recommendations.pdf

Amos KA. The ethics of scholarly publishing: exploring differences in plagiarism and duplicate publication across nations. J Med Lib Assoc. 2014; 102: 87-91.

Bosch X, Hernández C, Pericas JM, Doti P, Marušić A. Misconduct Policies in High-Impact Biomedical Journals. PLoS One. 2012; 7: e51928.

Booth WC, Colomb GC, Williams JM. The Craft of Research, 3 rd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1995, 2008.

Rosselot Jaramillo E, Bravo Lechat M, Kottow Lang M, Valenzuela Yuraidini C, O’Ryan Gallardo M, Thambo Becker S, Horwitz Campos N, Acevedo Pérez I, Rueda Castro L, Angélica Sotomayor M. En referencia al plagio intelectual: Documento de la Comisión de Ética de la Facultat de Medicina de le Universidad de Chile. Rev Méd Chil. 2008; 136: 653-658.

PubMed Google Scholar

Maddox J. Plagiarism is worse than mere theft. Nature. 1995; 376: 721.

Olson KR, Shaw A. ‘No fair, copycat!’: what children’s response to plagiarism tells us about their understanding of ideas. Dev Sci. 2011; 14: 431-439.

Yang F, Shaw A, Garduno E, Olson KR. No one likes a copycat: A cross-cultural investigation of children’s response to plagiarism. J Exp Child Psychol. 2014; 121: 111-119.

Yilmaz I. Plagiarism? No, we’re just borrowing better English. Nature. 2007; 449: 658.

Vessal K, Habibzadeh F. Rules of the game of scientific writing: fair play and plagiarism. Lancet. 2007; 369: 641.

Afifi M. Plagiarism is not fair play. Lancet. 2007; 369: 1428.

World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Accessed on 10 January 2018 at: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/

Altman DG. The scandal of poor medical research. BMJ. 1994; 308: 283-284.

Abraham P. Duplicate and salami publications. J Postgrad Med. 2000; 46: 67-69.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Kassirer JP, Angell M. Redundant Publication: A Reminder. NEJM. 1995; 333: 449-450.

Bennie MJ, Lim CW. Salami publication. BMJ. 1992; 304: 1314.

Rogers LF. Salami Slicing, Shotgunning, and the Ethics of Authorship. Am J Roentgenol. 1999; 173: 265.

Huth EJ. Irresponsible Authorship and Wasteful Publication. Ann Intern Med. 1986; 104: 257-259.

The cost of salami slicing. Nat Mat. 2005; 4: 1.

Chalmers I, Glasziou P. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Lancet. 2009; 374: 86-89.

MacCallum CJ. Reporting Animal Studies: Good Science and a Duty of Care. PLoS Biol. 2010; 8: e1000413.

Frank E. Publish or perish: the moral imperative of journals. CMAJ. 2016: 188: 675.

The PLoS Medicine Editors. An Unbiased Scientific Record Should Be Everyone’s Agenda. PLoS Med. 2009; 6: 0119-0121.

Rosenthal R. The “File Drawer Problem” and Tolerance for Null Results. Psychol Bull. 1979; 86: 638-641.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Montori V, Vist G, Kunz R, Brozek J, Alonso-Coello P, Djulbegovic B, Atkins D, Falck-Ytter Y, Williams JW Jr., Meerpohl J, Norris SL, Akl EA, Schünemann HJ. GRADE guidelines: 5. Rating the quality of evidence—publication bias. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011; 64: 1277-1282.

Chalmers TC, Frank CS, Reitman D. Minimizing the Three Stages of Publication Bias. JAMA. 1990; 263: 1392-1395.

von Elm E, Costanza MC, Walder B, Tramèr MR. More insight into the fate of biomedical meeting abstracts: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003; 3: 12.

Weber EJ, Callaham ML, Wears RL, Barton C, Young G. Unpublished Research from a Medical Specialty Meeting: Why Investigators Fail to Publish. JAMA. 1998; 280: 257-259.

Sprague S, Bhandari M, Devereaux PJ, Swiontkowski MF, Tornetta P III, Cook DJ, Dirschl D, Schemitsch EH, Guyatt GH. Barriers to Full-Text Publication Following Presentation of Abstracts at Annual Orthopaedic Meetings. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003; 85-A: 158-163.

Smith MA, Barry HC, Williamson J, Keefe CW, Anderson WA. Factors Related to Publication Success Among Faculty Development Fellowship Graduates. Fam Med. 2009; 41: 120-125.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Mercury Medical Research & Writing, New York, NY, USA

Michael Hanna

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Hanna, M. (2019). Ethics of Scientific Writing. In: How to Write Better Medical Papers. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02955-5_21

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02955-5_21

Published : 21 March 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-02954-8

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-02955-5

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Site Search

- How to Search

- Advisory Group

- Editorial Board

- OEC Fellows

- History and Funding

- Using OEC Materials

- Collections

- Research Ethics Resources

- Ethics Projects

- Communities of Practice

- Get Involved

- Submit Content

- Open Access Membership

- Become a Partner

Introduction: What is Research Ethics?

Research Ethics is defined here to be the ethics of the planning, conduct, and reporting of research. This introduction covers what research ethics is, its ethical distinctions, approaches to teaching research ethics, and other resources on this topic.

What is Research Ethics

Why Teach Research Ethics

Animal Subjects

Biosecurity

Collaboration

Conflicts of Interest

Data Management

Human Subjects

Peer Review

Publication

Research Misconduct

Social Responsibility

Stem Cell Research

Whistleblowing

Descriptions of educational settings , including in the classroom, and in research contexts.

Case Studies

Other Discussion Tools

Information about the history and authors of the Resources for Research Ethics Collection

What is Research Ethics?

Research Ethics is defined here to be the ethics of the planning, conduct, and reporting of research. It is clear that research ethics should include:

- Protections of human and animal subjects

However, not all researchers use human or animal subjects, nor are the ethical dimensions of research confined solely to protections for research subjects. Other ethical challenges are rooted in many dimensions of research, including the:

- Collection, use, and interpretation of research data

- Methods for reporting and reviewing research plans or findings

- Relationships among researchers with one another

- Relationships between researchers and those that will be affected by their research

- Means for responding to misunderstandings, disputes, or misconduct

- Options for promoting ethical conduct in research

The domain of research ethics is intended to include nothing less than the fostering of research that protects the interests of the public, the subjects of research, and the researchers themselves.

Ethical Distinctions

In discussing or teaching research ethics, it is important to keep some basic distinctions in mind.

- It is important not to confuse moral claims about how people ought to behave with descriptive claims about how they in fact do behave. From the fact that gift authorship or signing off on un-reviewed data may be "common practice" in some contexts, it doesn't follow that they are morally or professionally justified. Nor is morality to be confused with the moral beliefs or ethical codes that a given group or society holds (how some group thinks people should live). A belief in segregation is not morally justified simply because it is widely held by a group of people or given society. Philosophers term this distinction between prescriptive and descriptive claims the 'is-ought distinction.'

- A second important distinction is that between morality and the law. The law may or may not conform to the demands of ethics (Kagan, 1998). To take a contemporary example: many believe that the law prohibiting federally funded stem cell research is objectionable on moral (as well as scientific) grounds, i.e., that such research can save lives and prevent much human misery. History is full of examples of bad laws, that is laws now regarded as morally unjustifiable, e.g., the laws of apartheid, laws prohibiting women from voting or inter-racial couples from marrying.

- It is also helpful to distinguish between two different levels of discussion (or two different kinds of ethical questions): first-order or "ground-level" questions and second-order questions.

- First-order moral questions concern what we should do. Such questions may be very general or quite specific. One might ask whether the tradition of 'senior' authorship should be defended and preserved or, more generally, what are the principles that should go into deciding the issue of 'senior' authorship. Such questions and the substantive proposals regarding how to answer them belong to the domain of what moral philosophers call 'normative ethics.'

- Second-order moral questions concern the nature and purpose of morality itself. When someone claims that falsifying data is wrong, what exactly is the standing of this claim? What exactly does the word 'wrong' mean in the conduct of scientific research? And what are we doing when we make claims about right and wrong, scientific integrity and research misconduct? These second-order questions are quite different from the ground-level questions about how to conduct one's private or professional life raised above. They concern the nature of morality rather than its content, i.e., what acts are required, permitted or prohibited. This is the domain of what moral philosophers call 'metaethics' (Kagan, 1998).

Ethical Approaches

Each of these approaches provides moral principles and ways of thinking about the responsibilities, duties and obligations of moral life. Individually and jointly, they can provide practical guidance in ethical decision-making.

- One of the most influential and familiar approaches to ethics is deontological ethics, associated with Immanuel Kant (1742-1804). Deontological ethics hold certain acts as right or wrong in themselves, e.g., promise breaking or lying. So, for example, in the context of research, fraud, plagiarism and misrepresentation are regarded as morally wrong in themselves, not simply because they (tend to) have bad consequences. The deontological approach is generally grounded in a single fundamental principle: Act as you would wish others to act towards you OR always treat persons as an end, never as a means to an end.

- From such central principles are derived rules or guidelines for what is permitted, required and prohibited. Objections to principle-based or deontological ethics include the difficulty of applying highly general principles to specific cases, e.g.: Does treating persons as ends rule out physician-assisted suicide, or require it? Deontological ethics is generally contrasted to consequentialist ethics (Honderich, 1995).

- According to consequentialist approaches, the rightness or wrongness of an action depends solely on its consequences. One should act in such a way as to bring about the best state of affairs, where the best state of affairs may be understood in various ways, e.g., as the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people, maximizing pleasure and minimizing pain or maximizing the satisfaction of preferences. A theory such as Utilitarianism (with its roots in the work of Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill) is generally taken as the paradigm example of consequentialism. Objections to consequentialist ethics tend to focus on its willingness to regard individual rights and values as "negotiable." So, for example, most people would regard murder as wrong independently of the fact that killing one person might allow several others to be saved (the infamous sacrifice of an ailing patient to provide organs for several other needy patients). Similarly, widespread moral opinion holds certain values important (integrity, justice) not only because they generally lead to good outcomes, but in and of themselves.

- Virtue ethics focuses on moral character rather than action and behavior considered in isolation. Central to this approach is the question what ought we (as individuals, as scientists, as physicians) to be rather than simply what we ought to do. The emphasis here is on inner states, that is, moral dispositions and habits such as courage or a developed sense of personal integrity. Virtue ethics can be a useful approach in the context of RCR and professional ethics, emphasizing the importance of moral virtues such as compassion, honesty, and respect. This approach has also a great deal to offer in discussions of bioethical issues where a traditional emphasis on rights and abstract principles frequently results in polarized, stalled discussions (e.g., abortion debates contrasting the rights of the mother against the rights of the fetus).

- The term 'an ethics of care' grows out of the work of Carol Gilligan, whose empirical work in moral psychology claimed to discover a "different voice," a mode of moral thinking distinct from principle-based moral thinking (e.g., the theories of Kant and Mill). An ethics of care stresses compassion and empathetic understanding, virtues Gilligan associated with traditional care-giving roles, especially those of women.

- This approach differs from traditional moral theories in two important ways. First, it assumes that it is the connections between persons, e.g., lab teams, colleagues, parents and children, student and mentor, not merely the rights and obligations of discrete individuals that matter. The moral world, on this view, is best seen not as the interaction of discrete individuals, each with his or her own interests and rights, but as an interrelated web of obligations and commitment. We interact, much of the time, not as private individuals, but as members of families, couples, institutions, research groups, a given profession and so on. Second, these human relationships, including relationships of dependency, play a crucial role on this account in determining what our moral obligations and responsibilities are. So, for example, individuals have special responsibilities to care for their children, students, patients, and research subjects.

- An ethics of care is thus particularly useful in discussing human and animal subjects research, issues of informed consent, and the treatment of vulnerable populations such as children, the infirm or the ill.

- The case study approach begins from real or hypothetical cases. Its objective is to identify the intuitively plausible principles that should be taken into account in resolving the issues at hand. The case study approach then proceeds to critically evaluate those principles. In discussing whistle-blowing, for example, a good starting point is with recent cases of research misconduct, seeking to identify and evaluate principles such as a commitment to the integrity of science, protecting privacy, or avoiding false or unsubstantiated charges. In the context of RCR instruction, case studies provide one of the most interesting and effective approaches to developing sensitivity to ethical issues and to honing ethical decision-making skills.

- Strictly speaking, casuistry is more properly understood as a method for doing ethics rather than as itself an ethical theory. However, casuistry is not wholly unconnected to ethical theory. The need for a basis upon which to evaluate competing principles, e.g., the importance of the well-being of an individual patient vs. a concern for just allocation of scarce medical resources, makes ethical theory relevant even with case study approaches.

- Applied ethics is a branch of normative ethics. It deals with practical questions particularly in relation to the professions. Perhaps the best known area of applied ethics is bioethics, which deals with ethical questions arising in medicine and the biological sciences, e.g., questions concerning the application of new areas of technology (stem cells, cloning, genetic screening, nanotechnology, etc.), end of life issues, organ transplants, and just distribution of healthcare. Training in responsible conduct of research or "research ethics" is merely one among various forms of professional ethics that have come to prominence since the 1960s. Worth noting, however, is that concern with professional ethics is not new, as ancient codes such as the Hippocratic Oath and guild standards attest (Singer, 1986).

- Adams D, Pimple KD (2005): Research Misconduct and Crime: Lessons from Criminal Science on Preventing Misconduct and Promoting Integrity. Accountability in Research 12(3):225-240.

- Anderson MS, Horn AS, Risbey KR, Ronning EA, De Vries R, Martinson BC (2007): What Do Mentoring and Training in the Responsible Conduct of Research Have To Do with Scientists' Misbehavior? Findings from a National Survey of NIH-Funded Scientists . Academic Medicine 82(9):853-860.

- Bulger RE, Heitman E (2007): Expanding Responsible Conduct of Research Instruction across the University. Academic Medicine. 82(9):876-878.

- Kalichman MW (2006): Ethics and Science: A 0.1% solution. Issues in Science and Technology 23:34-36.

- Kalichman MW (2007): Responding to Challenges in Educating for the Responsible Conduct of Research, Academic Medicine. 82(9):870-875.

- Kalichman MW, Plemmons DK (2007): Reported Goals for Responsible Conduct of Research Courses. Academic Medicine. 82(9):846-852.

- Kalichman MW (2009): Evidence-based research ethics. The American Journal of Bioethics 9(6&7): 85-87.

- Pimple KD (2002): Six Domains of Research Ethics: A Heuristic Framework for the Responsible Conduct of Research. Science and Engineering Ethics 8(2):191-205.

- Steneck NH (2006): Fostering Integrity in Research: Definitions, Current Knowledge, and Future Directions. Science and Engineering Ethics 12:53-74.

- Steneck NH, Bulger RE (2007): The History, Purpose, and Future of Instruction in the Responsible Conduct of Research. Academic Medicine. 82(9):829-834.

- Vasgird DR (2007): Prevention over Cure: The Administrative Rationale for Education in the Responsible Conduct of Research. Academic Medicine. 82(9):835-837.

- Aristotle. The Nichomachean Ethics.

- Beauchamp RL, Childress JF (2001): Principles of Biomedical Ethics, 5th edition, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Bentham, J (1781): An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation.

- Gilligan C (1993): In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women's Development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Glover, Jonathan (1977): Penguin Books.

- Honderich T, ed. (1995): The Oxford Companion to Philosophy, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kagan S (1998): Normative Ethics. Westview Press.

- Kant I (1785): Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals.

- Kant I (1788): Critique of Practical Reason.

- Kant I (1797): The Metaphysics of Morals.

- Kant I (1797): On a Supposed right to Lie from Benevolent Motives.

- Kuhse H, Singer P (1999): Bioethics: An Anthology. Blackwell Publishers.

- Mill JS (1861): Utilitarianism.

- Rachels J (1999): The Elements of Moral Philosophy, 3rd edition, Boston: McGraw-Hill.

- Regan T (1993): Matters of Life and Death: New Introductory Essays in Moral Philosophy, 3rd edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. The history of ethics.

- Singer P (1993): Practical Ethics, 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press.

The Resources for Research Ethics Education site was originally developed and maintained by Dr. Michael Kalichman, Director of the Research Ethics Program at the University of California San Diego. The site was transferred to the Online Ethics Center in 2021 with the permission of the author.

Related Resources

Submit Content to the OEC Donate

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Award No. 2055332. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Research Methods

- Introduction

- Key Resources

- Books, Articles & Videos

What is Research Ethics?

Research misconducts, responsible conduct of research, youtube video.

- Methods by Subject

Research ethics provides guidelines for the responsible conduct of research. In addition, it educates and monitors scientists conducting research to ensure a high ethical standard. The following is a general summary of some ethical principles:

Honestly report data, results, methods and procedures, and publication status. Do not fabricate, falsify, or misrepresent data.

Objectivity:

Strive to avoid bias in experimental design, data analysis, data interpretation, peer review, personnel decisions, grant writing, expert testimony, and other aspects of research.

Keep your promises and agreements; act with sincerity; strive for consistency of thought and action.

Carefulness:

Avoid careless errors and negligence; carefully and critically examine your own work and the work of your peers. Keep good records of research activities.

Share data, results, ideas, tools, resources. Be open to criticism and new ideas.

Respect for Intellectual Property:

Honor patents, copyrights, and other forms of intellectual property. Do not use unpublished data, methods, or results without permission. Give credit where credit is due. Never plagiarize.

Confidentiality:

Protect confidential communications, such as papers or grants submitted for publication, personnel records, trade or military secrets, and patient records.

Responsible Publication:

Publish in order to advance research and scholarship, not to advance just your own career. Avoid wasteful and duplicative publication.

Responsible Mentoring:

Help to educate, mentor, and advise students. Promote their welfare and allow them to make their own decisions.

Respect for Colleagues:

Respect your colleagues and treat them fairly.

Social Responsibility:

Strive to promote social good and prevent or mitigate social harms through research, public education, and advocacy.

Non-Discrimination:

Avoid discrimination against colleagues or students on the basis of sex, race, ethnicity, or other factors that are not related to their scientific competence and integrity.

Competence:

Maintain and improve your own professional competence and expertise through lifelong education and learning; take steps to promote competence in science as a whole.

Know and obey relevant laws and institutional and governmental policies.

Animal Care:

Show proper respect and care for animals when using them in research. Do not conduct unnecessary or poorly designed animal experiments.

Human Subjects Protection:

When conducting research on human subjects, minimize harms and risks and maximize benefits; respect human dignity, privacy, and autonomy.

Source: What is Ethics in Research & Why is it Important? U.S. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences

- Five Principles for Research Ethics (American Psychological Association)

- Ethical Guidelines for Good Research Practice (Association of Social Anthropologists, UK)

- Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research, 2018 (Australian Government)

- ESRC Framework for Research Ethics 2015 (The Economic and Social Research Council, UK)

How different aspects of your research relate to the six ethics principles set out in the ESRC Framework for Research Ethics? Click the image below to find out.

http://www.ethicsguidebook.ac.uk/EthicsPrinciples

What are research misconducts?

(a) Fabrication - making up data or results and recording or reporting them.

(b) Falsification - manipulating research materials, or changing or omitting data or results such that the research is not accurately represented in the research record.

(c) Plagiarism - the appropriation of another person's ideas, processes, results, or words without giving appropriate credit.

(d) Research misconduct does not include honest error or differences of opinion.

Source: Definition of Research Misconduct The Office of Research Integrity, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

ORI Introduction to the Responsible Conduct of Research

Yale School of Medicine Professor Robert Levine spoke on guidelines for human subjects protection.

Video from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jD-YCDE_5yw

- << Previous: Books, Articles & Videos

- Next: Methods by Subject >>

- Last Updated: Jan 17, 2024 7:25 PM

- URL: https://libguides.library.cityu.edu.hk/researchmethods

© City University of Hong Kong | Copyright | Disclaimer

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples

Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples

Published on 7 May 2022 by Pritha Bhandari .

Ethical considerations in research are a set of principles that guide your research designs and practices. Scientists and researchers must always adhere to a certain code of conduct when collecting data from people.

The goals of human research often include understanding real-life phenomena, studying effective treatments, investigating behaviours, and improving lives in other ways. What you decide to research and how you conduct that research involve key ethical considerations.

These considerations work to:

- Protect the rights of research participants

- Enhance research validity

- Maintain scientific integrity

Table of contents

Why do research ethics matter, getting ethical approval for your study, types of ethical issues, voluntary participation, informed consent, confidentiality, potential for harm, results communication, examples of ethical failures, frequently asked questions about research ethics.

Research ethics matter for scientific integrity, human rights and dignity, and collaboration between science and society. These principles make sure that participation in studies is voluntary, informed, and safe for research subjects.

You’ll balance pursuing important research aims with using ethical research methods and procedures. It’s always necessary to prevent permanent or excessive harm to participants, whether inadvertent or not.

Defying research ethics will also lower the credibility of your research because it’s hard for others to trust your data if your methods are morally questionable.

Even if a research idea is valuable to society, it doesn’t justify violating the human rights or dignity of your study participants.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Before you start any study involving data collection with people, you’ll submit your research proposal to an institutional review board (IRB) .

An IRB is a committee that checks whether your research aims and research design are ethically acceptable and follow your institution’s code of conduct. They check that your research materials and procedures are up to code.

If successful, you’ll receive IRB approval, and you can begin collecting data according to the approved procedures. If you want to make any changes to your procedures or materials, you’ll need to submit a modification application to the IRB for approval.

If unsuccessful, you may be asked to re-submit with modifications or your research proposal may receive a rejection. To get IRB approval, it’s important to explicitly note how you’ll tackle each of the ethical issues that may arise in your study.

There are several ethical issues you should always pay attention to in your research design, and these issues can overlap with each other.

You’ll usually outline ways you’ll deal with each issue in your research proposal if you plan to collect data from participants.

Voluntary participation means that all research subjects are free to choose to participate without any pressure or coercion.

All participants are able to withdraw from, or leave, the study at any point without feeling an obligation to continue. Your participants don’t need to provide a reason for leaving the study.

It’s important to make it clear to participants that there are no negative consequences or repercussions to their refusal to participate. After all, they’re taking the time to help you in the research process, so you should respect their decisions without trying to change their minds.

Voluntary participation is an ethical principle protected by international law and many scientific codes of conduct.

Take special care to ensure there’s no pressure on participants when you’re working with vulnerable groups of people who may find it hard to stop the study even when they want to.

Informed consent refers to a situation in which all potential participants receive and understand all the information they need to decide whether they want to participate. This includes information about the study’s benefits, risks, funding, and institutional approval.

- What the study is about

- The risks and benefits of taking part

- How long the study will take

- Your supervisor’s contact information and the institution’s approval number

Usually, you’ll provide participants with a text for them to read and ask them if they have any questions. If they agree to participate, they can sign or initial the consent form. Note that this may not be sufficient for informed consent when you work with particularly vulnerable groups of people.

If you’re collecting data from people with low literacy, make sure to verbally explain the consent form to them before they agree to participate.

For participants with very limited English proficiency, you should always translate the study materials or work with an interpreter so they have all the information in their first language.

In research with children, you’ll often need informed permission for their participation from their parents or guardians. Although children cannot give informed consent, it’s best to also ask for their assent (agreement) to participate, depending on their age and maturity level.

Anonymity means that you don’t know who the participants are and you can’t link any individual participant to their data.

You can only guarantee anonymity by not collecting any personally identifying information – for example, names, phone numbers, email addresses, IP addresses, physical characteristics, photos, and videos.

In many cases, it may be impossible to truly anonymise data collection. For example, data collected in person or by phone cannot be considered fully anonymous because some personal identifiers (demographic information or phone numbers) are impossible to hide.

You’ll also need to collect some identifying information if you give your participants the option to withdraw their data at a later stage.

Data pseudonymisation is an alternative method where you replace identifying information about participants with pseudonymous, or fake, identifiers. The data can still be linked to participants, but it’s harder to do so because you separate personal information from the study data.

Confidentiality means that you know who the participants are, but you remove all identifying information from your report.

All participants have a right to privacy, so you should protect their personal data for as long as you store or use it. Even when you can’t collect data anonymously, you should secure confidentiality whenever you can.

Some research designs aren’t conducive to confidentiality, but it’s important to make all attempts and inform participants of the risks involved.

As a researcher, you have to consider all possible sources of harm to participants. Harm can come in many different forms.

- Psychological harm: Sensitive questions or tasks may trigger negative emotions such as shame or anxiety.

- Social harm: Participation can involve social risks, public embarrassment, or stigma.

- Physical harm: Pain or injury can result from the study procedures.

- Legal harm: Reporting sensitive data could lead to legal risks or a breach of privacy.

It’s best to consider every possible source of harm in your study, as well as concrete ways to mitigate them. Involve your supervisor to discuss steps for harm reduction.

Make sure to disclose all possible risks of harm to participants before the study to get informed consent. If there is a risk of harm, prepare to provide participants with resources, counselling, or medical services if needed.

Some of these questions may bring up negative emotions, so you inform participants about the sensitive nature of the survey and assure them that their responses will be confidential.

The way you communicate your research results can sometimes involve ethical issues. Good science communication is honest, reliable, and credible. It’s best to make your results as transparent as possible.

Take steps to actively avoid plagiarism and research misconduct wherever possible.

Plagiarism means submitting others’ works as your own. Although it can be unintentional, copying someone else’s work without proper credit amounts to stealing. It’s an ethical problem in research communication because you may benefit by harming other researchers.

Self-plagiarism is when you republish or re-submit parts of your own papers or reports without properly citing your original work.

This is problematic because you may benefit from presenting your ideas as new and original even though they’ve already been published elsewhere in the past. You may also be infringing on your previous publisher’s copyright, violating an ethical code, or wasting time and resources by doing so.

In extreme cases of self-plagiarism, entire datasets or papers are sometimes duplicated. These are major ethical violations because they can skew research findings if taken as original data.

You notice that two published studies have similar characteristics even though they are from different years. Their sample sizes, locations, treatments, and results are highly similar, and the studies share one author in common.

Research misconduct

Research misconduct means making up or falsifying data, manipulating data analyses, or misrepresenting results in research reports. It’s a form of academic fraud.

These actions are committed intentionally and can have serious consequences; research misconduct is not a simple mistake or a point of disagreement about data analyses.

Research misconduct is a serious ethical issue because it can undermine scientific integrity and institutional credibility. It leads to a waste of funding and resources that could have been used for alternative research.

Later investigations revealed that they fabricated and manipulated their data to show a nonexistent link between vaccines and autism. Wakefield also neglected to disclose important conflicts of interest, and his medical license was taken away.

This fraudulent work sparked vaccine hesitancy among parents and caregivers. The rate of MMR vaccinations in children fell sharply, and measles outbreaks became more common due to a lack of herd immunity.

Research scandals with ethical failures are littered throughout history, but some took place not that long ago.

Some scientists in positions of power have historically mistreated or even abused research participants to investigate research problems at any cost. These participants were prisoners, under their care, or otherwise trusted them to treat them with dignity.

To demonstrate the importance of research ethics, we’ll briefly review two research studies that violated human rights in modern history.

These experiments were inhumane and resulted in trauma, permanent disabilities, or death in many cases.

After some Nazi doctors were put on trial for their crimes, the Nuremberg Code of research ethics for human experimentation was developed in 1947 to establish a new standard for human experimentation in medical research.

In reality, the actual goal was to study the effects of the disease when left untreated, and the researchers never informed participants about their diagnoses or the research aims.

Although participants experienced severe health problems, including blindness and other complications, the researchers only pretended to provide medical care.

When treatment became possible in 1943, 11 years after the study began, none of the participants were offered it, despite their health conditions and high risk of death.

Ethical failures like these resulted in severe harm to participants, wasted resources, and lower trust in science and scientists. This is why all research institutions have strict ethical guidelines for performing research.

Ethical considerations in research are a set of principles that guide your research designs and practices. These principles include voluntary participation, informed consent, anonymity, confidentiality, potential for harm, and results communication.

Scientists and researchers must always adhere to a certain code of conduct when collecting data from others .

These considerations protect the rights of research participants, enhance research validity , and maintain scientific integrity.

Research ethics matter for scientific integrity, human rights and dignity, and collaboration between science and society. These principles make sure that participation in studies is voluntary, informed, and safe.

Anonymity means you don’t know who the participants are, while confidentiality means you know who they are but remove identifying information from your research report. Both are important ethical considerations .

You can only guarantee anonymity by not collecting any personally identifying information – for example, names, phone numbers, email addresses, IP addresses, physical characteristics, photos, or videos.

You can keep data confidential by using aggregate information in your research report, so that you only refer to groups of participants rather than individuals.

These actions are committed intentionally and can have serious consequences; research misconduct is not a simple mistake or a point of disagreement but a serious ethical failure.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2022, May 07). Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 9 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/ethical-considerations/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, data collection methods | step-by-step guide & examples, how to avoid plagiarism | tips on citing sources.

Research Writing & Ethics Interns

Research writing & ethics internship.

Led by Teachers College (TC) Institutional Review Board (IRB) and in collaboration with the Graduate Writing Center (GWC) , Graduate Student Life & Development (GSLD) , and TC NEXT , the Research Writing & Ethics Internship is a 10-week, 10 hours per week opportunity for students to develop professional competencies in research careers.

Student interns who participate in this program...

- Accomplish challenging, but realistic tasks.

- Develop professional competencies for career success.

- Use the knowledge gained for specific research, writing, and ethics skills.

- Collaborate in a team environment and learn about campus research structures.

- Gain an opportunity to develop specific and measurable goals.

- Network with departments and colleagues .

Spring 2024 Interns & Projects

Sabrina zhao.

Outreach & Career Development Intern

Sabrina Zhao is a first-year master’s student in the International Educational Development program at Teachers College, Columbia University. She received her Bachelor’s degree in Film & Media and Gender Studies from Queen’s University in 2023. Her research interests are situated at the intersection of media, education, and culture, framed within a decolonial perspective.

Sabrina Zhao is a first-year master’s student in the International Educational Development program at Teachers College, Columbia University. She received my Bachelor’s degree in Film & Media and Gender Studies from Queen’s University in 2023. Her research interests are situated at the intersection of media, education, and culture, framed within a decolonial perspective. She is particularly focused on exploring the technological and cultural factors influencing educational practices, with a specific emphasis on literacy, social justice, youth development, and teacher education. In collaboration with TC Next, she plans to organize informative panels dedicated to discussing Institutional Review Board (IRB) processes. These panels aim to provide a platform for open dialogue and comprehensive discussions surrounding the crucial aspects of navigating the IRB system. Additionally, she will create blogs specifically designed to address the distinct needs of international students, offering insights and guidance tailored to the unique challenges they may encounter in their academic journeys.

Public Speaking & Networking Intern

Jiayi is a second-year master’s student in Comparative and International Education program at Teachers College. She received her Bachelor’s Degree in Political Science and International Relationship from Tongji University, China in 2022. Her research interests focus on literacy education, language ideologies and international organizations in global educational networks.

During her time in the internship, Jiayi is planning to create a public presentation series in collaboration with GSLD on demystifying the IRB process and exploring international research settings and ethical considerations.

Research Writing Inter

Jimin Kim is a first-year master’s student in the Clinical Psychology program at Teachers College, Columbia University. She received her Bachelor’s degree in Psychology at the Ohio State University in 2022. Jimin hopes to delve into the accurate and specific identifications of risk and protective factors, especially for suicide and depression in different stages of life, by integrating the latest technologies.

Fall 2023 Interns & Projects

Lily daniels.

Research Writing Intern

Lily is a second-year master’s student in the Clinical Psychology program at Teachers College. She received her Bachelor’s Degree in Psychology and History of Science from Johns Hopkins University in 2021. Her undergraduate research focused on the relationship between temperamental dimensions and pediatric obsessive compulsive disorder. She partnered with the Graduate Writing Center for her internship.