Education and Health System in Bangladesh Essay

Introduction, education system in bangladesh, healthcare system in bangladesh, works cited.

Bangladesh is a developing country located in south Asia. Since ancient times, Bangladesh culture and economy has been influenced by China and India. At the end of the 20 th century, the country developed a national system of education and healthcare based on international principles and standards. Thus, poor economic development of the country and lack of financial support of the government present these systems from rapid growth and development. Bangladesh has long been integrated into the politics and economy of the global world. Though, this cultural and social globalization is accompanied by a thinning of internal solidarity. Today, elite Bangladesh citizens have increasing amounts in common (economically, politically and culturally) with English speakers elsewhere in the world, but experience increasing detachment from the mass of the national society.

Education in Bangladesh consists of three stages. The government of Bangladesh controls primary, secondary and high secondary education. the five main categories of education are: (1) General Education System, (2) Madrasah Education System, (3) Technical – Vocational Education System, (4) Professional Education System, (5) Other Education Systems. In Bangladesh, primary education and health care are free. An amazing official statistic informs us that %100 (sic) of all children in the appropriate age band are educated in primary schools. The UN Human Development Index suggests that only % 55 of children go to school during the first three years. The census gathers data on literacy; in 1991 the literacy rate was %41.1, male literacy %53 and female % 35. Since the acceptance of the standard of liberalization, there has been an support of welfare and educational development provision via non-governmental organizations (Literacy in Bangladesh 2009). The best of these can be excellent, but they can be erratic in their education provision and far too many are either amateurish or corrupt. NGOs receive the bulk of their funding from the Government of Bangladesh, not (as many critics assume) from charities. Directly or indirectly, the state of Bangladesh continues to be the major provider in the education field and it is to be hoped that it will hold this role for a very long time, with the proviso that there be sufficient controlling of the actions of educators (Education in Bangladesh 2009).

A special type of colleges introduced by the government is cadet colleges. These institutions can be compared to public schools in Britain. Bangladesh spends a small proportion of its education budget on primary schools and a remarkably large amount on higher education including graduate and post-graduate programs. The poor provision of free schooling implies that a disproportionate number of unreserved places at the highly subsidized universities are won by those people who have received a private schooling – a good issue for those citizens who can afford it to invest in the school days of their children, but also a good issues for them not to be concerned to raise standards in public schools. it is important to note that the group of professionals and bureaucrats reproduces itself through its appropriation of higher education of a high standard. High education is crucial for public employees as it determines a degree of career development and pay structure (Education 2009).

In Bangladesh, education has long been an important issue of controversy as it was provided in the English language only. The Board of education introduced new rules and obliged teachers to educate children on the native language. Thus, many upper-class families want to educate their children expensively in the most exclusive British language schools and universities. This expenditure results in professions which are internationally recognized and open up employment opportunities on a international scale; but such professions and diplomas also put a candidate in a very strong position when challenging for senior positions in national and international corporations in Bangladesh. in the country, private schooling in English is seen an essential necessity of the affluent middle classes and above and, as a consequence, school fees have a previous claim on household income over consumer goods. Although the mass media often reports on the material over-indulgence of middle-class citizens, the reality is that the big expenditure on children of both genders is in terms of their education, rather than their leisure issues or possessions (Heitzman and Worden 2002).

In spite of these changes, the government education has very low standards of provision and high incidence of teacher absenteeism. The state lacks 15,5% of primary teachers. The school curriculum is dull and uninspiring and levels of achievement of many children are low. As a consequence, middle-class cities do everything they can to educate their children in the many small private, profit-making, English-medium schools, often not of high standard of education and with underqualified teachers (Heitzman and Worden 2002).

In Bangladesh, a good public-school in a major city has high fees a year. The education of children of the upper classes is persistently directed towards high personal achievement; even very young children are given corrective amounts of homework and nervous parents employ tutors after hours to keep them up to scratch in their weaker subjects. Also, there are instruction in various activities such as music and drawing. The boys and girls are taught a great deal but education all too often takes the form of rote learning and pouring new knowledge and skills into them, rather than encouraging their own abilities. Many of the children are made competitive and taught to win because their parents know that places in the super elite are scarce (Education 2009). At the beginning of the 21 st century, there is an educated class of people in Bangladesh often with qualifications much higher than one would expect for their standard of living and type of employment. Many citizens of Bangladesh have university degrees and virtually all males have completed 12 years of schooling. This category of society is literate, informed and politically active. It performs a considerable demand for TV news and periodicals. For all this, it is not always intellectual in its tastes.

Health care in Bangladesh consists of private and public sectors. Following WHO, “Bangladesh has made significant progress in recent times in many of its social development indicators particularly in health” (Bangladesh Healthcare WHO 2009). Thus, views are sharply divided as to whether increased integration into the global economy causes a healthcare revolution and the end of mass poverty. Advocates of the free market and deregulation claim that healthcare will take time to work, others are skeptical as to whether it works at all. Bangladesh remains the World Bank’s biggest borrower. Ill health in the family can cause serious suffering to people in the lower middle classes as they try to afford private healthcare. This becomes particularly acute if hospital treatment is required. Many plan for this by taking out health insurance policies (Bangladesh Healthcare 2009). There are no significant welfare payments for people who become chronically sick and cannot work; people try to save against this and hope they can rely on family reciprocal care. Members of the upper middle class have good healthcare insurance cover which allows them to visit the best private clinics and hospitals equipped to international standards (the very rich go abroad for major surgery). “The public sector is largely used for in-patient and preventive care while the private sector is used mainly for outpatient curative care. Primary Health Care (PHC) has been chosen by the Government of Bangladesh as the strategy to achieve the goals of “Health for all” which is now being implemented as Revitalized Primary Health Care” (Bangladesh Healthcare WHO 2009).

A significant section of Bangladesh healthcare is dedicated to socialist principles and to social causes. There is a thriving healthcare movement; there are anti-corruption campaigns; there is support for healthcare, welfare and education programs for poor people in urban and rural areas; there is a considerable concern for the environment and a growing anti-nuclear movement; there is agitation on human rights issues and opposition to communalist tendencies. Many of the citizens of the slums are ‘ecological refugees’, those people forced from the land by ‘development’ or environmental degradation. It was estimated that there are 3 million people in Bangladesh who have been displaced from their homes by ‘development’ projects. Given that there is a shortage of cultivable land a significant but unknown proportion of these come as destitute to the urban centers with few relevant skills and only their labor to sell, refugees in their own country. Urban poverty is intimately connected with poor health provision and inadequate services. As a consequence, so long as there is greater economic growth in the towns than in the villages, economic growth will not lead to increased wages for urban workers. Urban poverty declines only when there is a growth in regulated labor intensive industries but, the tendency has been towards investment in high productivity, capital intensive industry with ancillary outsourcing of labor concentrated production in the informal sector, where wages are driven down by the excess of available unskilled and semi-skilled labor (Bangladesh Healthcare 2009).

In spite of great economic and social changes, the private system of healthcare is underdeveloped in Bangladesh. Thus, like other developing countries, Bangladesh introduces employment pensions and private medical insurance, preferential treatment in waiting lists for telephones and gas connections, reservation of seats on trains and in cinemas, and the sympathetic treatment of old people in public healthcare. “In the private sector, there are traditional healers (Kabiraj, totka, and faith healers like pir / fakirs), homeopathic practitioners, village doctors (rural medical practitioners RMPs/ Palli Chikitsoks-PCs), community health workers (CHWs) and finally, retail drugstores that sell allopathic medicine on demand” (Bangladesh Healthcare WHO 2009). That is to say, it is an entirely cosmetic exercise. In a country where good medical care is exorbitantly expensive, where there are few support agencies and where there is no right to a state pension, elderly people can hardly be expected to greet an increasing individualization and market orientation with enthusiasm. They need to be able to claim their rights as citizens; however, old people, particularly frail old people, are less able than younger women to organize themselves in resistance (Bangladesh Healthcare 2009).

In sum, the education and healthcare system in Bangladesh is underdeveloped and suffers from lack of financial support and qualified professionals. Poor education and inadequate healthcare lead to social problems and health problems experienced by the majority of society. Today, the new social classes consist of citizens who in the past would almost certainly have not made their careers. Minor changes in education and healthcare open up new opportunities for the population to enter trade and business and participate in economic relations and service provision.

Bangladesh Healthcare. WHO . 2009. Web.

Bangladesh Healthcare. 2009. Web.

Education in Bangladesh. People republic of Bangladesh . 2009. Web.

Education. Bangladesh education and resource Center . 2009. Web.

Literacy in Bangladesh. 2009. Web.

James Heitzman and Robert Worden, editors. Bangladesh: A Country Study . Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 2002.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, December 7). Education and Health System in Bangladesh. https://ivypanda.com/essays/education-and-health-system-in-bangladesh/

"Education and Health System in Bangladesh." IvyPanda , 7 Dec. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/education-and-health-system-in-bangladesh/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Education and Health System in Bangladesh'. 7 December.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Education and Health System in Bangladesh." December 7, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/education-and-health-system-in-bangladesh/.

1. IvyPanda . "Education and Health System in Bangladesh." December 7, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/education-and-health-system-in-bangladesh/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Education and Health System in Bangladesh." December 7, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/education-and-health-system-in-bangladesh/.

- Economic Development of Bangladesh

- How Bangladesh Got Its Independence

- Corruption: A Development Problem of Bangladesh

- Concepts of the Economic Development and Microfinance in Bangladesh

- Bangladesh Police Institution

- Industrial Engineering in Bangladesh and Belgium

- EnGlobal Logistics Expanding into Bangladesh

- Bangladesh's International Textile Trade

- Comparison of Pakistan and Bangladesh

- Climate Change Impact on Bangladesh

- Strategic Planning in the Schools

- “How to Make It in College, Now You’re There” by Brian O’Keeney

- Paradigm Shift on the Way Education Is Conducted

- Defining Student Affairs: Educator, Leader and Administrator

- The Maclean’s Survey of Canadian Universities

A case for building a stronger health care system in Bangladesh

Md rafi hossain, shakil ahmed.

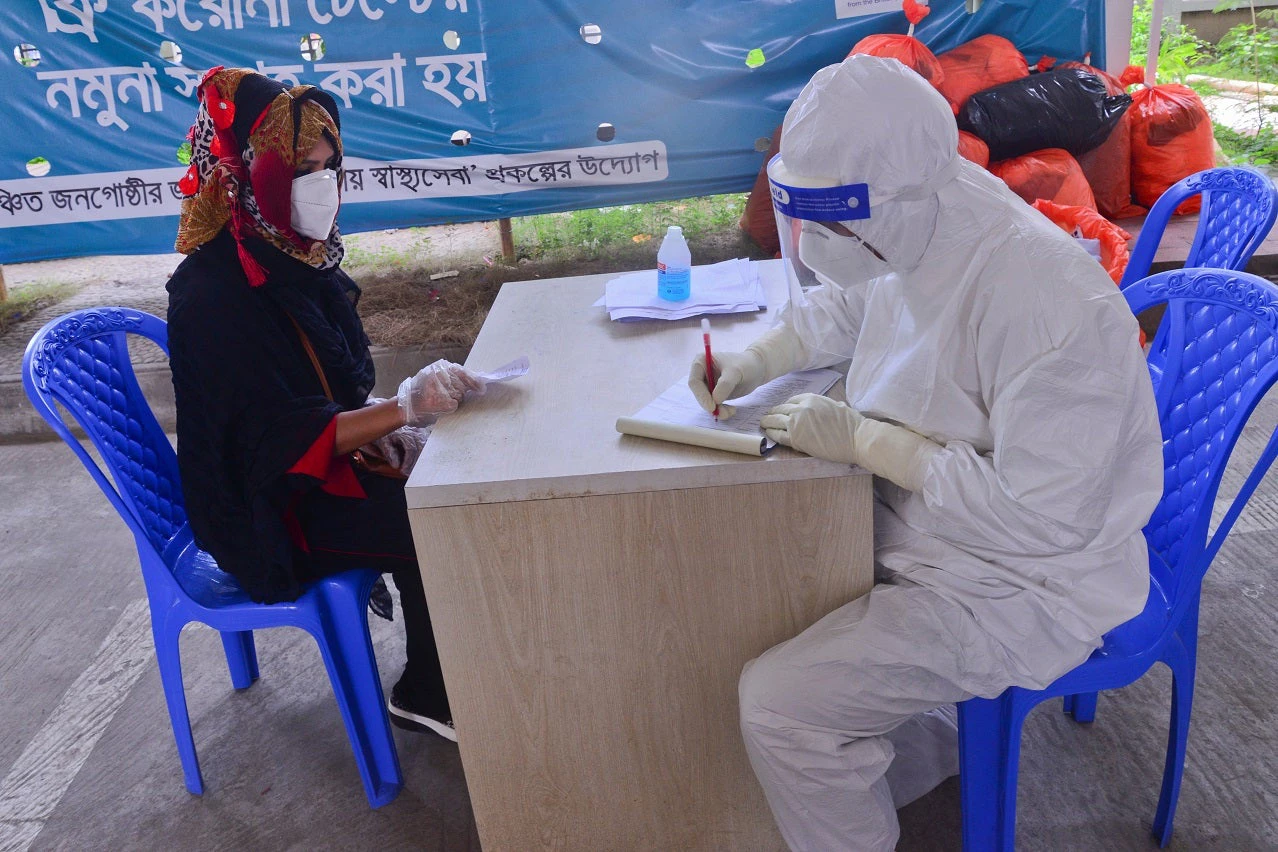

From poor management to the quality of available health care, the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed many vulnerabilities in health care systems across South Asian countries, including Bangladesh. As we respond to and learn from this crisis, it presents an important opportunity for the country to re-examine the health care sector, including the need for strategic allocation of resources .

On June 30, the Bangladesh Parliament passed the FY21 budget with increased allocations to sectors dealing with the effects of COVID-19, including the health, education, agriculture, and social welfare sectors. The proposed expenditure of BDT 5,680 billion ($ 66.8 billion), was 8.6 percent higher than the original FY20 budget. BDT 292.5 billion ($ 3.4 billion) has been allocated to the health sector, up from BDT 257.3 ($ 3.0 billion) in the original FY20 budget, a nominal increase of 13.7 percent.

Allocation to the health sector stands at 5.14 percent of the total FY21 budget and is less than 1 percent of GDP. This low expenditure towards health is not a new phenomenon.

While this is certainly a step in the right direction, is it enough?

Currently, due to the relatively low allocation of budget to the sector, individuals have to bear a large share of medical costs, with 67 percent of expenses borne by households through out-of-pocket payments. Allocation to the health sector stands at 5.14 percent of the total FY21 budget and is less than 1 percent of GDP. This low expenditure towards health in Bangladesh is not a new phenomenon. For many years, the government’s budget allocation to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW) has been hovering around the 5 percent mark. In 2017, health expenditure was 2.3 percent of GDP , substantially lower than the South Asian and Lower Middle Income Country (LMIC) average at 5.3 percent and 5.4 percent of GDP .

Support from development partners has always been an important source of health financing in Bangladesh. The World Bank and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) have signed agreements of $100 million each for strengthening government systems for COVID-19 response. Without this support, the proposed allocation to health would be 4.8 percent of the budget, which would represent an increase in allocation of only BDT 18.7 billion ($0.2 billion) or 7 percent compared to the original FY20 budget.

So, what are some of the options available to the government?

Refocus attention to the health care sector and adopt and implement a longer-term strategy to further strengthen its capacity. Even without the COVID-19 pandemic, increased budgetary allocation is needed to address some of the critical shortages of trained human resources (both medical and managerial), medical equipment, and supplies. In addition, with Bangladesh gradually becoming a middle-income country, support from development partners will decline. The government will, therefore, need to mobilize its own resources to fill this void.

Support reforms towards a robust public financial management (PFM) system to improve transparency in the sector. The MOHFW needs to efficiently use the existing resources that are available through better planning and management of the sector. As a recent World Bank paper on Strengthening Health Finance and Service Delivery in Bangladesh, illustrates, effective PFM in the health sector will help to address problems with delay in fund availability, recruitment and retention of human resources, delay in procurement of drugs and medical supplies, and lack of provision for allocating operational funds at the facility level. This will certainly strengthen health service delivery at district level and below.

The global COVID-19 pandemic provides an opportunity for the government to reprioritize health in the national agenda. If Bangladesh is to stay on track towards attaining the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 3) of achieving Universal Health Coverage, this is an opportunity the country cannot afford to miss.

- COVID-19 (coronavirus)

- Human Capital

Operations Officer

Senior Economist (Health)

Join the Conversation

- Share on mail

- comments added

- Help & FAQ

The health care system in Bangladesh: an insight into health policy, law and governance

- Macquarie Law School

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article › peer-review

- health and well-being

- Healthcare system

- Health governance

- policy and legislation

- institutions

Access to Document

- https://ssrn.com/abstract=3553045

Fingerprint

- Health Care System Social Sciences 100%

- Bangladesh Social Sciences 98%

- health policy Social Sciences 93%

- Healthcare Social Sciences 76%

- governance Social Sciences 64%

- Law Social Sciences 52%

- Corrupt practices Social Sciences 28%

- Medical malpractice Social Sciences 26%

T1 - The health care system in Bangladesh

T2 - an insight into health policy, law and governance

AU - Karim, Sheikh Mohammad Towhidul

AU - Alam, Shawkat

N2 - Bangladesh has suffered from numerous healthcare crises. As a country that is rapidly developing and becoming more urbanised, new healthcare challenges await in the form of non-communicable and chronic diseases that are commonly associated with industrialised economies. Yet, despite these new challenges, many of the institutions, laws and policies which govern the provision of healthcare in Bangladesh remain weak. To date, patients have no real recourse to submit complaints concerning medical malpractice and the enforcement culture fails to promote accountability amongst practicing medical professionals. This article reviews and evaluates the healthcare framework with particular regard to patient safety legislation and the supporting tools and institutions that promote patient safety in Bangladesh. Through the lens of governance theory, this article assesses Bangladesh’s healthcare governance framework in accordance with two key indicators developed by the World Bank: government effectiveness and regulatory burden. This article finds that many existing practices remain uncompetitive, creating unnecessary cost barriers to patients. It also finds that existing practices are non-transparent, and that government effectiveness is undermined by corrupt practices and an ineffective oversight mechanism. This article advocates for the effective promotion and enforcement of a Citizen Charter of Rights, as well as further regulatory and institutional reform to promote patient rights and improve health outcomes.

AB - Bangladesh has suffered from numerous healthcare crises. As a country that is rapidly developing and becoming more urbanised, new healthcare challenges await in the form of non-communicable and chronic diseases that are commonly associated with industrialised economies. Yet, despite these new challenges, many of the institutions, laws and policies which govern the provision of healthcare in Bangladesh remain weak. To date, patients have no real recourse to submit complaints concerning medical malpractice and the enforcement culture fails to promote accountability amongst practicing medical professionals. This article reviews and evaluates the healthcare framework with particular regard to patient safety legislation and the supporting tools and institutions that promote patient safety in Bangladesh. Through the lens of governance theory, this article assesses Bangladesh’s healthcare governance framework in accordance with two key indicators developed by the World Bank: government effectiveness and regulatory burden. This article finds that many existing practices remain uncompetitive, creating unnecessary cost barriers to patients. It also finds that existing practices are non-transparent, and that government effectiveness is undermined by corrupt practices and an ineffective oversight mechanism. This article advocates for the effective promotion and enforcement of a Citizen Charter of Rights, as well as further regulatory and institutional reform to promote patient rights and improve health outcomes.

KW - health and well-being

KW - Healthcare system

KW - Health governance

KW - policy and legislation

KW - institutions

M3 - Article

SN - 1839-4191

JO - Australian Journal of Asian Law

JF - Australian Journal of Asian Law

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Health Serv Insights

Healthcare Systems Strengthening in Smaller Cities in Bangladesh: Geospatial Insights From the Municipality of Dinajpur

Shaikh mehdi hasan.

1 Health Systems and Population Studies Division, icddr,b, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Kyle Gantuangco Borces

2 Department of Global Health, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA

Dipika Shankar Bhattacharyya

Shakil ahmed.

3 Centre of Excellence for Urban Equity and Health, BRAC James P Grant School of Public Health, BRAC University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

4 Country Office, Bangladesh, Options Consultancy Services UK Ltd., Dhaka, Bangladesh

Alayne Adams

5 Department of Family Medicine, McGill University, Montréal, Québec, Canada

Throughout South Asia a proliferation of cities and middle-sized towns is occurring. While larger cities tend to receive greater attention in terms national level investments, opportunities for healthy urban development abound in smaller cities, and at a moment where positive trajectories can be established. In Bangladesh, municipalities are growing in size and tripled in number especially district capitals. However, little is known about the configuration of health services to hold these systems accountable to public health goals of equity, quality, and affordability. This descriptive quantitative study uses data from a GIS-based census and survey of health facilities to identify gaps and inequities in services that need to be addressed. Findings reveal a massive private sector and a worrisome lack of primary and some critical care services. The study also reveals the value of engaging municipal-level decision makers in mapping activities and analyses to enable responsive and efficient healthcare planning.

Introduction

In the last several decades, South Asia has seen remarkable growth in the size and number of cities. In addition to megacities with populations greater than 10 million, middle-sized towns and cities will significantly contribute toward a projected 250 million increase in urban population by 2030. 1 In comparison to megacities, however, medium-sized cities with populations between 1 and 5 million inhabitants or smaller cities with less than 1 million residents in Africa and Asia display the fastest urban growth rates. In fact, the majority of the world’s fastest growing urban centers are smaller cities with only 500 000 to 1 million inhabitants, accounting for 26 out of 43 fastest growing cities in the world. 1 Despite these trends, disproportionate global attention has focused on larger cities especially in low and middle income countries. 2

A similar neglect of small and mid-sized cities is apparent in Bangladesh with its centralized government structure tending to privilege public expenditures on Dhaka, the political and economic capital, and the port city of Chittagong. 3 The potential of smaller municipalities as centers of economic growth and alternate destinations for urban migrants has been comparatively overlooked. 4 In Bangladesh, municipalities with less than 500 000 residents have actually tripled in number (104-318) between 1991 and 2007 especially within district and divisional capitals where public tertiary services are located. 5 Today, around 40% of urban population resides in municipalities across the country. 4 With rapid rural to urban migration, and increasing economic activity, small and mid-sized municipalities in Bangladesh are expanding in terms of surface area, population density, and per capita income. 6 Even though municipalities in Bangladesh comprise about 40% of the urban population, state investments in basic public health services are lacking at this level. 4 Unlike rural Bangladesh where health services are hierarchically organized under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW) from tertiary hospital to community clinic, in urban areas the governance and provision of health services is bifurcated between 2 major ministries. 7 The MOHFW is responsible for public tertiary and some secondary hospitals, Primary Health care (PHC) services, confined to a handful of urban dispensaries, and school health clinics. According to the Local Government Act, 2009, the Ministry of Local Government, Rural Development and Cooperatives (MOLGRD&C) is charged with PHC provision within local government institutions (LGIs) (municipalities and City Corporations). 8 Lacking in capacity and resources to provide these services, for the last 2 decades, urban PHC services have been contracted out to local Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) through the donor-funded Urban Primary Health Care Service Delivery Project . 7 Under the current phase of the project, contracted out services are offered in 21 City Corporations and 14 municipalities. 9 Filling the vacuum in publically-provided healthcare in urban areas, is a massive, growing and diverse private-for-profit sector. Comprised of private clinics, diagnostic centers and hospitals, as well as individual doctor’s chambers and informal drug sellers, this sector provides a range of curative services at hours and locations convenient to urban dwellers. 10 The high out-of-pocket expenditures that households shoulder in Bangladesh (73.88%) are largely a function of medical costs incurred in the private sector, and can have impoverishing consequences for the urban poor. 10 , 11

Limited knowledge exists regarding the configuration of municipal health services in Bangladesh, and the capacity of municipalities to hold these systems accountable to the public health goals of equity, quality, and affordability. In order to ensure equitable and quality services to all urban citizen especially to the urban poor, it is vital that both national and local decision-makers anticipate and plan for the healthcare needs of growing populations living in smaller cities.

Toward this end, a mapping study was commissioned by the DFID-funded Urban Health Systems Strengthening Project (UHSSP) to document the healthcare landscape of Dinajpur municipality and in particular, the availability and geographic accessibility of services to the urban poor. The mapping exercise was undertaken with the dual goals of increasing the awareness of municipal-level authorities regarding their cities’ current healthcare capacity and informing efforts to address health system deficiencies. This paper presents findings from this mapping study by describing both the healthcare landscape and overall experience of engaging municipal-level decision makers in the exercise. It aims to identify gaps and inequities in services that need to be addressed while reflecting on their implications for municipal governance and priority-setting toward achieving equitable service coverage in smaller cities.

Study site and population

The data used in this study originate from a health facility mapping census conducted in Dinajpur Municipality in 2016. Dinajpur municipality is located in the northern-most district of Bangladesh, approximately 400 km northwest of Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh. It is one of the oldest municipalities in the country, with a total population of 206 234 spread across12 administrative wards, each of which has an elected public representative. 12 , 13 There are also 5 extension areas of Dinajpur Municipality slotted for eventual inclusion into the municipality’s jurisdiction. Geographically, the Dinajpur municipality area skirts the river Punarbhaba, and occupies a land area of 20.23 square kilometres. 13 A City health planning exercise supported by a donor-funded project was ongoing in Dinajpur during the study period. It was an opportunity to leverage the existing platform to use the health facility maps generated through the mapping exercise. Since Dinajpur is one of the oldest municipalities in Bangladesh, 12 many other municipalities have similar characteristics. Dinajpur municipality was selected for the above-mentioned reasons.

Study design

This descriptive quantitative study consists of a GIS-based census and survey of health facilities. An application compatible for tablet computer was developed for facility listing and survey. Features included in the app were the ability to record and track GPS coordinates, capture road networks (including the type and width), insert facility locations, perform surveys on the inserted facilities using the digital version of the questionnaire, and insert key landmarks. The app included ward boundaries/study boundaries and also satellite images for accurate GPS tracking and survey. All recorded data were saved locally on the tab either in MySQL database or in JSON (Javascript Object Notation Format) so that the app can work without any active internet connection. All operating health facilities were included in the facility listing, and all formal health care providers, with the exception of those operating private doctor chambers, were included in the health facility survey.

Facility census and survey

Data collection occurred over the period March to April in 2016. Prior to field level activities, permission from respective Municipality authorities was obtained including the Mayor, Civil Surgeon, Directorate General of Health Services, and Directorate General of Family Planning. Written confirmation was also obtained from the NGO partners working in the municipality. A data collection team was formed and trained over a 5 day period. Data collection involved a 2-step process starting with a health facility listing of all operating facilities, followed by a health facility survey which focused on facilities with sufficient infrastructure and personnel to support a spectrum of services. Data collectors physically visited health facilities and collected information from clinic managers, hospital superintendents and in few occasions from doctors. We were able to collect information from the all the facilities included in the survey. Survey data included the type of health facility, management entity involved, facility focus, service hours, staffing pattern, qualifications and training, and services offered. A total of 806 facilities were listed and among these listed facilities, 207 health facilities were surveyed following the inclusion criteria. Since prior permissions were obtained, and multiple visits were made in instances when respondents were not available, data collectors were successful in collecting information from all the facilities targeted for inclusion in the survey.

Data analysis

Health facility data were analyzed using Stata 13 statistical analysis software and MS Excel. Descriptive statistics were performed to generate frequency tables and graphs. Geographic Information System (GIS) coordinates were collected for each facility and represented visually on base maps relative to ward-wise population using ArcGIS 10.2. Based on these maps and associated data, specific questions regarding geographic accessibility and service coverage were explored.

Ethical considerations

The study received ethical clearance from the Ethical Review Committee of icddr,b on 16 April 2014 (PR-13100). Permission was also sought from relevant authorities prior to facility census and survey. Written consent was taken from the respondents prior to the survey. Participation was completely voluntary, and efforts were made to collect service information at the respondent’s convenience to minimize disruptions to normal business activities.

Operational definitions

Operational definitions of health facilities are described in the following table 1 .

Operational definitions of health facilities.

Distribution

The large majority facilities listed in Dinajpur were managed by the private sector: out of 806 facilities, 83.6% were managed by private-for-profit sector with the remaining managed by NGOs (12.3%) and the public sector (3.9%).

Among the 207 facilitates surveyed in Dinajpur ( Table 2 ), 117 offered services at a static, dedicated location. Of these, 2 hospitals and 7 clinics were managed by the public sector while the private-for-profit and NGO sector accounted for a total of 5 hospitals and 51 clinics. A total of 90 satellite clinics were identified offering services during limited hours and days of the week or month. Apart from 2 satellite clinics and 20 state-provided Expanded Program on Immunization centers, the majority of satellite clinics were managed by NGOs and largely involved a single paramedic registering patients and providing referral services. Out of 4 standalone blood banks, 3 were operated by NGOs and 1 by the private sector. However, apart from these standalone blood banks, many hospitals and clinics possessed their own blood bank.

Number, types, and distribution of surveyed health facilities in Dinajpur municipality.

As shown in Table 3 , general health and curative services, such as diabetes, blood transfusion, pharmacy, maternal health, etc., were available across all health facilities in Dinajpur Municipality. However, capacity for emergency services such as cardiac care unit was limited to 1 public hospital and 1 NGO only, with the same NGO being the sole facility equipped with an Intensive Care Unit. No neonatal intensive care services were found in the municipality. It is worth mentioning that although private-for-profit facilities offer the highest numbers of surgical services, none reported having critical care capacity. NGOs are much more involved in the provision of family planning and health education services compared to public or private-for-profit private facilities.

Reported availability of major health services.

Table 4 demonstrates substantial variations in the cost of selected health care services in Dinajpur municipality comparing public, private-for-profit and NGO facilities. Public facilities were available free of charge, sometimes involving a nominal registration fee. NGO facilities also provided health services affordable to the poor by means of subsidized or free services and health cards, along with the provision of regular services which are priced below what is charged in private-for-profit facilities. For example, the median cost for a pregnancy ultrasonogram in the public sector was 110 BDT, which was 250 BDT in private-not-for-profit facilities, and 500 BDT in private-for-profit facilities. Similarly, median ECG charges were 80 BDT in a public facility and 500 BDT in a private facility; while normal vaginal delivery could cost 1000 BDT in an NGO and up to 5000 BDT in a private facility.

Cost of selected health services by management entity in Dinajpur municipality.

As seen in Figure 1 , an unequal distribution of static government health facilities in relation to population density, was observed. Among 10 static public facilities in Dinajpur, the Ministry of Health managed 8 facilities while the remaining 2 were managed by the municipal authority under the Ministry of Local Government. Most of these facilities were concentrated in only 4 of its 12 wards, leaving some wards with high population densities (ranging from 9000 to 20 000 persons per square kilometre) comparatively uncovered. In ward 1, for example, the population density was as high as 8775 per square kilometre, yet no government facility was available in that area.

Distribution of all static facilities.

As shown in Figure 1 , private facilities predominantly clustered around public facilities. For example, a significant number of private facilities were located within close proximity of Dinajpur Medical College.

This unequal distribution is particularly apparent in the southern and northern part of Dinajpur municipality where facility concentration is lower.

Service gaps

According to the Local Government Acts of 2009, local government institutions are responsible for providing primary healthcare in urban areas. 8 However, at the time of study, Dinajpur was not part of the current extension of the Urban Primary Health Care Project which supports the provision of PHC services in cities and municipalities through contracting-out arrangements with NGOs. Rather, independent NGOs were the primary provider of PHC services in Dinajpur, supplemented by a singular Outdoor Dispensary operated by the Ministry of Health.

In terms of emergency services, huge gaps were revealed including a lack of Neonatal Intensive Care services. In addition, only 2 facilities respectively were found to possess intensive care, burn unit capacity. Only 2 facilities, 1 public and 1 private not-for-profit, were reported to provide coronary care services in Dinajpur, both found in the Southeastern part of the municipality. The public facility, located in the extension area of the municipality, is equipped with coronary care and burn units, while intensive care and coronary care services are available in the private sector facility.

Service hours

Figure 2 reveals a large variation in service hours comparing facilities managed by public, private or NGO sector. Hospitals, clinics, diagnostic centers, blood banks, doctor chambers, and drop-in centers are included in this analysis. The majority of public and NGO facilities offered services up to 5 pm. By contrast, private-for-profit health facilities such as hospitals, clinics and diagnostic centers were open after 5 pm. Among the 10 public facilities in Dinajpur, only 3 provided services after 5 pm. In Dinajpur among 50 facilities providing 24/7 care, 38 were private, 3 public, and 9 were NGO facilities. NGO-run facilities mainly provided services during day time and morning hours.

Pattern of service hours by management entity in Dinajpur Municipality.

As shown in Figure 3 , large geographic gaps in 24/7 services are also apparent. For example, in Dinajpur, there was no public 24/7 facility in the highly dense northern part of the city (wards 1, 4, 6). A similar unequal distribution of 24/7 facilities is apparent for the private-for-profit sector since the large majority of private-for-profit 24/7 facilities are clustered in wards 3, 8, and 9.

Distribution of critical care and24/7 services in Dinajpur Municipality.

Engagement of municipal-level authorities

Municipal-level engagement was an important component of our mapping exercise to ensure that facility listing and survey activities were accurate and complete, but more importantly, that resulting maps were widely disseminated and used. Engagement with local-level authorities was initiated in January 2016 and permission for the mapping exercise was obtained in February 2016. The health facility mapping exercise was executed between March 2016 and April 2016. Local authorities started city health planning activities immediately after completion of the mapping exercise. During the post-mapping period, regular communication was maintained with the Municipal authority, Civil Surgeon, and other stakeholders in Dinajpur up to June 2016. At the design phase of the study, we brought a stakeholder group together comprised of municipal authorities, local representative of the Ministry of Health, as well as NGOs and private-for-profit providers. They were informed about our purpose and methods, and engaged in ensuring that necessary permissions were enabled. After the completion of mapping activities, findings were shared and validated through a series of workshops involving the same stakeholders, as well as representatives at both ward, and central levels. During these workshops, stakeholders discussed gaps and duplication in health service delivery, possible remedial actions, and potential applications of the maps for health systems governance and planning.

Encouragingly, follow-up revealed that maps were actively informing municipal planning activities. Local health coordination committees, chaired by the Mayor, with the district level Civil Surgeon as Vice Chair and the Municipal Health Officer as Member Secretary, were formed to review the current situation regarding healthcare provision in Dinajpur, and the maps produced by icddr,b were central to discussions on how to improve service coverage for the urban poor. Several concerns and remedial actions were identified with reference to facility maps. Municipal authorities noted the absence of service area demarcation among NGOs resulting in duplication of satellite and immunization sites and service gaps particularly in slums. To address the problem, maps were employed to identify and allocate catchment areas to NGO providers in these areas. NGOs reported consulting facility maps to determine where to establish new satellite and immunization centers and where merge such centers, with the goal of optimizing coverage of the referral and immunization services they provide. This was achieved without additional investment, through leveraging NGOs’ existing resources.

Rapid urbanization poses challenges to local and national governments related to growing urban demand for healthcare services, and the health risks accompanying unplanned growth. Among the issues of concern is the maldistribution of healthcare services relative to population needs, inadequacies in health human resources, weak regulation and quality, and rising hospital and medical costs. 14 These issues are even more acute in smaller cities which are growing in size and population, but with limited additional investment in healthcare provision. Recent global discourse emphasizes the value of urban spatial planning in integrating the public sector functions, for example, health, for sustainable urban development which is linked to the Sustainable Development Goals related to cities (SDG11). 15 In fact, city planning is now being regarded as a preventive health measure, and place-based indicators are increasingly considered fundamental to a systems approach to urban health and a crucial input to policy-making. 16 , 17

It is well established that evidence is key in ensuring equitable health services for all urban dwellers. 18 As such, this study provides an example of the value of geospatial data in revealing the maldistribution of healthcare services, and informing tangible action to rectify inequitable gaps in coverage. Study findings also point to specific issues of concern for Dinajpur with respect to the availability and geographic accessibility of services.

Availability

Perhaps the most concerning finding was the overall lack of urban public primary healthcare in Dinajpur in stark contrast with surrounding rural areas where a comprehensive system of public community clinics is in place that provide primary care services and referral to district and divisional hospitals throughout the country. 19 In Bangladesh, the few investments made in urban primary care have tended to privilege larger city corporations. For example, the Urban Primary Health Care Service Delivery Project operating in 21 cities and 14 municipalities across the country did not extend to Dinajpur at the time of study. 9 This bias in investment toward larger urban areas and the project’s centralized management structure has overlooked the need to strengthen municipal capacity in meeting the growing healthcare demands of their expanding populations. 7 Filling this vacuum in public provision is the fast growing urban private-for-profit sector. 20 It accounts for the largest number of facilities compared to public and NGO sectors. This finding is also similar to a GIS study conducted in Kaduna State in Nigeria, which found that the private sector accounted for majority of health facilities, and identified large inequities in the distribution of facilities across the state relative to needs. 21

Findings also indicate limited service hours in both public and NGO facilities which further exclude the working poor during daytime hours. While the majority of public and NGO health facilities close in the early afternoon, a significant number of private facilities are open in the evening and 24/7 which serve the working middle class. Among the urban poor, however, evidence from the literature suggests a preference for services from informal private facilities, especially drug shops, which dispense medication without prescription at hours and locations deemed more convenient than public, NGO or formal private sector facilities. (Health Systems and Population Studies Divison, icddr,b, unpublished report, April 2017).

Geographic accessibility

In terms of distribution, geospatial evidence revealed areas of the municipality where facility concentration was higher, and other pockets where service gaps were apparent. We also observed a particular concentration of private sector facilities around public facilities. This finding is consistent with a GIS study in Chittagong City Corporation indicating an uneven distribution of facilities and a clustering in 3 major zones, 22 and to analyses, we have conducted in other cities of Bangladesh. 23 - 25 Adopting an approach similar to our own, a study conducted in Cambodia also noted a high concentration of healthcare resources in areas with the lowest poverty rate. 26

Geospatial analysis further revealed concerning gaps in critical care. It is well known that timely and appropriate emergency care could avert a significant number of deaths and associated disabilities in low- and middle-income countries. 27 It is also established that health system planners often encounter difficulties ensuring access to trauma services. 28 Our findings indicate significant geographic gaps in coverage of comprehensive emergency and critical care health services including intensive care units, burn units, and neonatal intensive care units. Similar gaps are apparent in other cities in which mapping has occurred. 24

Implications for urban health governance

Evidence suggests that municipal authorities can play a pivotal role in reducing health disparities in cities. 29 Indeed, given their knowledge of local circumstances, they are better placed to identify and respond to gaps in services, and to harness opportunities to enable health coverage for their citizens. Study findings suggest that local municipalities can implement actions to improve health coverage by leveraging and redistributing existing resources if given the tools to do so. However, national-level action is also needed to address urban health governance challenges around regulation, accreditation, and the accountability of a system largely dominated by the private sector, as well as related concerns about escalating out of pocket payments for the urban poor. 30 These are system-level issues that municipalities cannot tackle alone, and which require state-level engagement and financing. Although municipal authorities are interested in improving city health infrastructure and healthcare access for their citizens, fiscal and administrative capacity constrain efforts to plan and implement corrective actions. 3 In this respect, state-level investments in building the capacity of municipal authorities to plan and manage healthcare provision, are also necessary. Finally, this study emphasizes the value of geospatial health facility information systems to help decision-makers identify service coverage service gaps and under-served populations, and their promise in improving the quality, equity, and efficiency of the overall health system.

Limitations

The facility mapping only listed informal healthcare providers but did not capture their details. All facility data on service provision and health human resources was reported by the facility concerned and quality of service was not assessed. The collection of population data including socio-demographic information and service utilization was not within the scope this study. A follow-up study that investigates whether the use of geospatial data for health planning has been sustained over the long-term will help establish the feasibility and impact of this approach.

Since municipalities in Bangladesh are shouldering an increasing proportion of the urban population, greater attention to health systems development is needed in terms of service delivery, capacity building and regulatory support. South Asian countries like Bangladesh can let unplanned urban growth continue or undertake policy reforms that leverage the untapped potential of agglomeration economies in cities. 31 Municipalities in Bangladesh also have the opportunity to assume a proactive approach toward planned urban development especially for the health sector and to ensure health services for all citizens. 32 As this paper argues, the availability of comprehensive information regarding the supply of healthcare services and their distribution across the urban landscape can assist the formulation of evidence-based strategies toward this end. Insights from geospatial data can contribute toward improved urban health service delivery, and even more so when local-level authorities are engaged in using maps to rectify coverage inequities. These findings may be valuable for other countries in the Asia Pacific region that are experiencing rapid urbanization.

Acknowledgments

Icddr,b acknowledges with gratitude the commitment of Options Consultancy Services Limited, UK to its research efforts. icddr,b is also grateful to the Governments of Bangladesh, Canada, Sweden, and the UK for providing core/unrestricted support. The authors are grateful to municipal authority, civil surgeon office, and private clinic owners association for providing permission to conduct the study.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study was funded by Options Consultancy Services Limited, UK.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: SMH conceptualized the paper, carried out the literature review, analysed the data, interpreted the results, prepared the first draft of the manuscript, revised it and prepared the final version for submission. KGB carried out the literature review, analysed the data, interpreted the results, and took part in the preparation of the draft manuscript. DSB carried out the literature review, interpreted the results, and took part in the preparation of the draft manuscript. SA analysed the data, interpreted the results, and took part in the preparation of the draft manuscript. AA critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. AMA conceptualized the paper, provided expert knowledge on urban health systems in Bangladesh, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Health Systems Reforms in Bangladesh: An Analysis of the Last Three Decades

- Find this author on Google Scholar

- Find this author on PubMed

- Search for this author on this site

- ORCID record for Thierno Oumar Fofana

- ORCID record for Shams Shabab Haider

- ORCID record for Lucie Clech

- ORCID record for Valéry Ridde

- For correspondence: [email protected]

- Info/History

- Supplementary material

- Preview PDF

Objective We reviewed the evidence regarding the health sector reforms implemented in Bangladesh within the past 30 years to understand their impact on the health system and healthcare outcomes.

Method We completed a scoping review of the most recent and relevant publications on health system reforms in Bangladesh from 1990 through 2023. Studies were included if they identified health sector reforms implemented in the last 30 years in Bangladesh, if they focused on health sector reforms impacting health system dimensions, if they were published between 1991 and 2023 in English or French and were full-text peer-reviewed articles, literature reviews, book chapters, grey literature, or reports.

Results Twenty-four studies met the inclusion criteria. The primary health sector reform shifted from a project-based approach to financing the health sector to a sector-wide approach. Studies found that implementing reform initiatives such as expanding community clinics and a voucher scheme improved healthcare access, especially for rural districts. Despite government efforts, there is a significant shortage of formally qualified health professionals, especially nurses and technologists, low public financing, a relatively high percentage of out-of-pocket payments, and significant barriers to healthcare access.

Conclusion Evidence suggests that health sector reforms implemented within the last 30 years had a limited impact on health systems. More emphasis should be placed on addressing critical issues such as human resources management and health financing, which may contribute to capacity building to cope with emerging threats, such as climate change.

Competing Interest Statement

The authors have declared no competing interest.

Clinical Protocols

https://www.example.com

Funding Statement

Funded by the French National Research Agency (ANR) as part of the presidential call; Make Our Planet Great Again; (MOPGA).

Author Declarations

I confirm all relevant ethical guidelines have been followed, and any necessary IRB and/or ethics committee approvals have been obtained.

I confirm that all necessary patient/participant consent has been obtained and the appropriate institutional forms have been archived, and that any patient/participant/sample identifiers included were not known to anyone (e.g., hospital staff, patients or participants themselves) outside the research group so cannot be used to identify individuals.

I understand that all clinical trials and any other prospective interventional studies must be registered with an ICMJE-approved registry, such as ClinicalTrials.gov. I confirm that any such study reported in the manuscript has been registered and the trial registration ID is provided (note: if posting a prospective study registered retrospectively, please provide a statement in the trial ID field explaining why the study was not registered in advance).

I have followed all appropriate research reporting guidelines, such as any relevant EQUATOR Network research reporting checklist(s) and other pertinent material, if applicable.

Data Availability

All the data used are in the text of this article.

View the discussion thread.

Supplementary Material

Thank you for your interest in spreading the word about medRxiv.

NOTE: Your email address is requested solely to identify you as the sender of this article.

Citation Manager Formats

- EndNote (tagged)

- EndNote 8 (xml)

- RefWorks Tagged

- Ref Manager

- Tweet Widget

- Facebook Like

- Google Plus One

Subject Area

- Public and Global Health

- Addiction Medicine (313)

- Allergy and Immunology (615)

- Anesthesia (157)

- Cardiovascular Medicine (2238)

- Dentistry and Oral Medicine (275)

- Dermatology (199)

- Emergency Medicine (367)

- Endocrinology (including Diabetes Mellitus and Metabolic Disease) (792)

- Epidemiology (11515)

- Forensic Medicine (10)

- Gastroenterology (674)

- Genetic and Genomic Medicine (3523)

- Geriatric Medicine (336)

- Health Economics (610)

- Health Informatics (2269)

- Health Policy (907)

- Health Systems and Quality Improvement (858)

- Hematology (332)

- HIV/AIDS (739)

- Infectious Diseases (except HIV/AIDS) (13103)

- Intensive Care and Critical Care Medicine (749)

- Medical Education (355)

- Medical Ethics (99)

- Nephrology (383)

- Neurology (3303)

- Nursing (189)

- Nutrition (502)

- Obstetrics and Gynecology (643)

- Occupational and Environmental Health (643)

- Oncology (1738)

- Ophthalmology (517)

- Orthopedics (206)

- Otolaryngology (283)

- Pain Medicine (220)

- Palliative Medicine (65)

- Pathology (433)

- Pediatrics (995)

- Pharmacology and Therapeutics (417)

- Primary Care Research (394)

- Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology (3029)

- Public and Global Health (5950)

- Radiology and Imaging (1211)

- Rehabilitation Medicine and Physical Therapy (710)

- Respiratory Medicine (803)

- Rheumatology (363)

- Sexual and Reproductive Health (343)

- Sports Medicine (307)

- Surgery (381)

- Toxicology (50)

- Transplantation (169)

- Urology (141)

Bangladesh's Economic and Social Progress pp 115–143 Cite as

Education, Health Care, and Life Expectancy in Bangladesh: Transcending Conventions

- Anis Pervez 2 &

- H. M. Jahirul Haque 3

- First Online: 01 April 2020

515 Accesses

1 Citations

Opposing the mainstream development economist’s argument that education does not necessarily have an economic return, we in this chapter offer a model of the triadic connection between education, health, and life expectancy—where each is positively correlated to the others. Such a correlation bore positive outcomes when state and non-state actors collaboratively worked in a country where the state is constrained by many limitations. In this chapter, with data and analysis, we show how state and non-state forces—NGOs and private sectors—have complemented each other and contributed to the progress of health care, education, and life expectancy in Bangladesh. We argue that development takes place as a collective exertion of state and non-state efforts. We further show how such a development model in Bangladesh is aligned with the UN Agenda 2030, necessitating everyone’s participation in transforming the world.

- Collective effort

- Human capital

- Life expectancy

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

For details, please visit— http://www.theindependentbd.com/post/147427 .

Acemoglu, D., & Johnson, S. (2006). Disease and development: The effect of life expectancy on economic growth . NBER Working Paper Series 12269, Cambridge, MA.

Google Scholar

Asadullah, M. N. (2005). Returns to education in Bangladesh . QEF Working Paper Series 130.

Asadullah, M. N. (2009). Returns to private and public education in Bangladesh and Pakistan: A comparative analysis . QEF Working Paper Series 167.

Asadullah, M. N., Savoia, A., & Mahmud, W. (2014). Paths to development: Is there a Bangladesh surprise? World Development, 62 , 138–154.

Article Google Scholar

BANBEIS. (2018). Bangladesh Education Statistics. Dhaka.

Bangladesh Population and Housing Census. (2011). Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Bangladesh Government.

Bangladesh University Grants Commission. (2017). Annual report . Dhaka.

Bangladesh Vocational Education Board. (2018). Annual report . Dhaka.

Blunch, N. H., & Das, M. B. (2015). Changing norms about gender inequality in education: Evidence from Bangladesh. Demographic Research, 32 (6), 183–218.

BRAC. (2018). BRAC’s youth policy tracking exercise (Draft).

Citizen’s Platform for SDGs, Bangladesh. (2019). Citizen conclave: Four years of SDGs in Bangladesh. Dhaka.

Guda, D. R., Khandaker, I. U., Parveen, S. D., & Whitson, T. (2004). Bangladesh: NGO and public sector tuberculosis service delivery—Rapid assessment results. Bethesda, MD: Quality Assurance Project.

Hossain, N. (2004). Access to education for the poor and girls: Educational achievements in Bangladesh . Paper presented at the scaling up poverty reduction: A global learning process conference, Shanghai, May 25–27, 2004.

Hossain, N. (2017). The aid lab: Understanding Bangladesh’s unexpected success . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Khan, A. (2018, July 16). Literacy and education, not the same. The Asian Age . Retrieved from https://dailyasianage.com/news/130740/literacy-and-education-not-the-same

Lerner, D. (1958). The passing of traditional society: Modernizing the Middle East . New York: Free Press.

Lim, S. S., Updike, R. L., Kaldjian, A. S., Barber, R. M., Cowling, K., York, H., … Murray, C. J. L. (2018). Measuring human capital: A systematic analysis of 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016. The Lancet, 392 (10154), 1217–1234.

Maruf, M. H. (2013). Health sector management of Bangladesh: An evaluation of BRAC’s health program . Dhaka: MAGD, BRAC University.

Mitaj, A., Muco, K., & Avdulaj, J. (2016). The role of human capital in the economic development and social welfare in Albania. International Journal of Human Resource Studies, 6 (1), 63–72.

Nisbett, N., Davis, P., Yosef, S., & Akhtar, N. (2017, June). Bangladesh’s story of change in nutrition: Strong improvements in basic and underlying determinants with an unfinished agenda for direct community level support. Global Food Security, 13 , 21–29.

Olshansky, S., Antonucci, T., Berkman, T., & Binstock, R. (2012). Differences in life expectancy due to race and educational differences are widening, and many may not catch up. Health Affairs, 31 (8). Retrieved from https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0746

Rahman, S. (2009). Farm productivity and efficiency in rural Bangladesh: The role of education revisited. Applied Economics, 41 (1), 17–33.

Rostow, W. W. (1960). The stages of economic growth: A non-communist manifesto . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sarker, A. E., & Nawaz, F. (2019, June 6). Adverse political incentives and obstinate behavioural norms: A study of social safety nets in Bangladesh. International Review of Administrative Sciences , 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852319829206

Sarker, V. K. (2015). BRAC’s innovation in health: A case study . Dhaka: MAGD, BRAC University.

SVRS. (2010). Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Bangladesh Government.

SVRS. (2017). Sample viral registration system. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics.

The Dhaka Tribune. (2017, April 25). Life expectancy in Bangladesh higher than world average. Retrieved from https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/2017/04/25/average-life-expectancy-bang

Ullah, A. N. Z., Newell, J. N., Ahmed, J. U., Hyder, M. K., & Islam, A. (2006). Government-NGO collaboration: The case of tuberculosis control in Bangladesh. Health Policy Plan, 21 (2), 43–55.

United Nations. (2016). The sustainable development goals (SDGs) are coming to life: Stories of country implementation and UN Support.

UNESCO. (1917). Global Education Monitoring Report . Paris.

WHO. (2018). Monitoring health for the SDGs: Stories of country implementation and UN Support. In World Health Statistics 2017 . Rome: World Health Organization.

Zohir, S. (2004). NGO sector in Bangladesh: An overview. Economic and Political Weekly, 39 (36), 4–10.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Bangladesh on Record, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Anis Pervez

University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh (ULAB), Dhaka, Bangladesh

H. M. Jahirul Haque

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

College of International Management, Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University, Beppu-shi, Oita, Japan

Munim Kumar Barai

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Pervez, A., Haque, H.M.J. (2020). Education, Health Care, and Life Expectancy in Bangladesh: Transcending Conventions. In: Barai, M. (eds) Bangladesh's Economic and Social Progress. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-1683-2_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-1683-2_4

Published : 01 April 2020

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-15-1682-5

Online ISBN : 978-981-15-1683-2

eBook Packages : Economics and Finance Economics and Finance (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Health System of Bangladesh

Related Papers

Stephanie Hill

VOICE OF RESEARCH

Priyanka Singh

Health is an essential quality in human being. It is defined as a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease (WHO, 2003). This definition intends to embrace the other components that contribute to positive health like spiritual, emotional, behavioral and cultural.

Basavaraj Biradar

British Medical Journal

Sjaak van der Geest

Evgeny G Bryndin

Despite many attempts to measure health, it wasn't offered any scale which would have practical value in this plan. Absence of the uniform point of view on a problem of essence of health is obvious. A specification of essence of health – the main methodological problem of the doctrine about health. The World Health Organization considers that a state of person health defines for 75% its way of life and a power supply system, for 10% - heredity, another 10% - environmental conditions, and only for 5% of service of health care. Health of the person most of all depends on a way of life. By definition of the World Health Organization (WHO), health is a condition of physical, spiritual and social wellbeing. Approach of WHO to concept health has humanitarian character. In article health is allocated in independent medico-social category which is characterized by direct indicators. The healthy nation is formed on the basis of a healthy way of life as family and social, cultural tradition. The cultural tradition of a healthy way of life unites complete adjustment of the person for a healthy condition, spiritual and physical training of longevity, social hygiene of mentality of the person from stresses and neurosises, neutralization of bad habits on stages of infringement of harmonious integrity of the person, harmonization of a way of life, health saving up medicine and health saving up system of public health services.

About 14% of the global burden of disease has been attributed to neuropsychiatric disorders, mostly due to the chronically disabling nature of depression and other common mental disorders, alcohol-use and substance-use disorders, and psychoses. Such estimates have drawn attention to the importance of mental disorders for public health. However, because they stress the separate contributions of mental and physical disorders to disability and mortality, they might have entrenched the alienation of mental health from mainstream efforts to improve health and reduce poverty. The burden of mental disorders is likely to have been underestimated because of inadequate appreciation of the connectedness between mental illness and other health conditions. Because these interactions are protean, there can be no health without mental health. Mental disorders increase risk for communicable and non-communicable diseases, and contribute to unintentional and intentional injury. Conversely, many health conditions increase the risk for mental disorder, and comorbidity complicates help-seeking, diagnosis, and treatment, and influences prognosis. Health services are not provided equitably to people with mental disorders, and the quality of care for both mental and physical health conditions for these people could be improved. We need to develop and evaluate psychosocial interventions that can be integrated into management of communicable and non-communicable diseases. Health-care systems should be strengthened to improve delivery of mental health care, by focusing on existing programmes and activities, such as those which address the prevention and treatment of HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria; gender-based violence; antenatal care; integrated management of childhood illnesses and child nutrition; and innovative management of chronic disease. An explicit mental health budget might need to be allocated for such activities. Mental health affects progress towards the achievement of several Millennium Development Goals, such as promotion of gender equality and empowerment of women, reduction of child mortality, improvement of maternal health, and reversal of the spread of HIV/AIDS. Mental health awareness needs to be integrated into all aspects of health and social policy, health-system planning, and delivery of primary and secondary general health care.

Skye Barbic , Emma Ware

Lack of consensus on the definition of mental health has implications for research, policy and practice. This study aims to start an international, interdisciplinary and inclusive dialogue to answer the question: What are the core concepts of mental health? 50 people with expertise in the field of mental health from 8 countries completed an online survey. They identified the extent to which 4 current definitions were adequate and what the core concepts of mental health were. A qualitative thematic analysis was conducted of their responses. The results were validated at a consensus meeting of 58 clinicians, researchers and people with lived experience. 46% of respondents rated the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC, 2006) definition as the most preferred, 30% stated that none of the 4 definitions were satisfactory and only 20% said the WHO (2001) definition was their preferred choice. The least preferred definition of mental health was the general definition of health adapted from ...

RELATED PAPERS

Crop Science

Joana Alves

Cancer Research

Nandini Katre

Archives of Ophthalmology

Agneta Rydberg

Zahiruddin Aqib

부산휴게텔≦Dalpocha5쩜cOm≧ 달포차

Neuroscience

Research, Society and Development

Oriel Herrera Bonilla

Journal of Agricultural Education

Leslie Thompson

CV CARDIGNI

Julieta Cardigni

Lecture Notes in Computer Science

Yingqin Zheng

Behavioral Sciences

Megan Blanton

Revista Interdisciplina

Karla Valenzuela

Duchowe korzenie błogosławionego Michała Giedroycia. Zakon Kanoników Regularnych od Pokuty

Marcin A. Klemenski

Molecular Biology of the Cell

Robert L Tanguay

International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications

Dr. Efosa C . IGODAN

Polymers for Advanced Technologies

Fitri Fitrilawati

Tariq Darabseh

arXiv (Cornell University)

Adel P. Kazemi

Mara Centeno

Physical Review E

Franck Plouraboué

Regional Environmental Change

Yasmina SanJuan

Frontiers in Marine Science

Roger C . Levesque

Salma Zahra

Gheorghe Jurj

See More Documents Like This

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Bangladesh Health System Review Health Systems in Transition Health Sy Vol. 5 No. 3 2015 s t ems in T r ansition V ol. 5 No. 3 2015 Bangladesh Health System Review The Asia Pacific Observatory on Health Systems and Policies (the APO) is a collaborative partnership of interested governments, international agencies, foundations, and researchers ...

Catastrophic health expenditure forces 5.7 million Bangladeshis into poverty. Inequity is present in most of health indicators across social, economic, and demographic parameters. This study explores the existing health policy environment and current activities to further the progress towards Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and the challenges ...

3. Development of a Strong and Accountable Primary Health Care System. Although Bangladesh has made notable strides in the development of a strong, effective, and affordable PHC system, it needs to give greater emphasis on the prevention, early identification, and ongoing treatment of noncommunicable diseases, almost all of which are chronic.

In Bangladesh, the healthcare system faces significant challenges, including limited resources, inadequate infrastructure, and a shortage of skilled healthcare professionals [15]. (Anwar et al ...

The government of Bangladesh controls primary, secondary and high secondary education. the five main categories of education are: (1) General Education System, (2) Madrasah Education System, (3) Technical - Vocational Education System, (4) Professional Education System, (5) Other Education Systems. In Bangladesh, primary education and health ...

BDT 292.5 billion ($ 3.4 billion) has been allocated to the health sector, up from BDT 257.3 ($ 3.0 billion) in the original FY20 budget, a nominal increase of 13.7 percent. Allocation to the health sector stands at 5.14 percent of the total FY21 budget and is less than 1 percent of GDP. This low expenditure towards health is not a new phenomenon.

Valid and reliable indicators against which progress towards global targets of 80% coverage of health services and 100% financial protection from catastrophic and impoverishing health-care costs can be assessed are crucial to achievement of universal health coverage (UHC). An even more ambitious project is to predict whether UHC targets will be met by 2030, and equitable gains achieved. In The ...

In November, 2013, the Lancet Series on Bangladesh highlighted the country as an exceptional and exemplary health performer in the south Asia region. This success was achieved despite Bangladesh having a weak health system, low health-care expenditure, and widespread poverty. Several political, social, and economic factors were identified as contributing to this success, including the national ...

Karim, Sheikh Mohammad Towhidul and Alam, Shawkat, The Health Care System in Bangladesh: An Insight into Health Policy, Law and Governance (March 12, 2020). Australian Journal of Asian Law, 2020, Vol 20 No 2, Article 6: 367-385, ... PAPERS. 11,412. This Journal is curated by: Donald C. Clarke at George Washington University ...

Health progress made in Bangladesh is impressive.1 In recognising this achievement, The Lancet Series on Bangladesh acknowledges the importance of the synergy between government, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and communities. It also rightly emphasises the progress towards equity as high-coverage programmes increasingly reach the poor, and especially women and girls, reducing ...

T1 - The health care system in Bangladesh. T2 - an insight into health policy, law and governance. AU - Karim, Sheikh Mohammad Towhidul. AU - Alam, Shawkat. PY - 2020. Y1 - 2020. N2 - Bangladesh has suffered from numerous healthcare crises. As a country that is rapidly developing and becoming more urbanised, new healthcare challenges await in ...

Study context, PHC system and health service delivery in Bangladesh. Bangladesh's health system is pluralistic, wherein multiple actors and providers play roles by applying a mixed system of medical practices. 48 The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare is the apex body for designing, formulating and overseeing health relation actions, and ...