Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER BRIEF

- 08 May 2019

Toolkit: How to write a great paper

A clear format will ensure that your research paper is understood by your readers. Follow:

1. Context — your introduction

2. Content — your results

3. Conclusion — your discussion

Plan your paper carefully and decide where each point will sit within the framework before you begin writing.

Collection: Careers toolkit

Straightforward writing

Scientific writing should always aim to be A, B and C: Accurate, Brief, and Clear. Never choose a long word when a short one will do. Use simple language to communicate your results. Always aim to distill your message down into the simplest sentence possible.

Choose a title

A carefully conceived title will communicate the single core message of your research paper. It should be D, E, F: Declarative, Engaging and Focused.

Conclusions

Add a sentence or two at the end of your concluding statement that sets out your plans for further research. What is next for you or others working in your field?

Find out more

See additional information .

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-01362-9

Related Articles

How to get published in high impact journals

So you’re writing a paper

Writing for a Nature journal

‘Woah, this is affecting me’: why I’m fighting racial inequality in prostate-cancer research

Career Q&A 20 MAR 24

So … you’ve been hacked

Technology Feature 19 MAR 24

Four years on: the career costs for scientists battling long COVID

Career Feature 18 MAR 24

How to stop ‘passing the harasser’: universities urged to join information-sharing scheme

News 18 MAR 24

People, passion, publishable: an early-career researcher’s checklist for prioritizing projects

Career Column 15 MAR 24

Postdoctoral Associate

Our laboratory at the Washington University in St. Louis is seeking a postdoctoral experimental biologist to study urogenital diseases and cancer.

Saint Louis, Missouri

Washington University School of Medicine Department of Medicine

Recruitment of Global Talent at the Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IOZ, CAS)

The Institute of Zoology (IOZ), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), is seeking global talents around the world.

Beijing, China

Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IOZ, CAS)

Postdoctoral Fellow-Proteomics/Mass Spectrometry

Location: Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA, USA Department: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Tulane University School of Med...

New Orleans, Louisiana

Tulane University School of Medicine (SOM)

Open Faculty Position in Mathematical and Information Security

We are now seeking outstanding candidates in all areas of mathematics and information security.

Dongguan, Guangdong, China

GREAT BAY INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDY: Institute of Mathematical and Information Security

Faculty Positions in Bioscience and Biomedical Engineering (BSBE) Thrust, Systems Hub, HKUST (GZ)

Tenure-track and tenured faculty positions at all ranks (Assistant Professor/Associate Professor/Professor)

The university is situated in the heart of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area, a highly active and vibrant region in the world.

The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (Guangzhou)

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Paper

Definition:

Research Paper is a written document that presents the author’s original research, analysis, and interpretation of a specific topic or issue.

It is typically based on Empirical Evidence, and may involve qualitative or quantitative research methods, or a combination of both. The purpose of a research paper is to contribute new knowledge or insights to a particular field of study, and to demonstrate the author’s understanding of the existing literature and theories related to the topic.

Structure of Research Paper

The structure of a research paper typically follows a standard format, consisting of several sections that convey specific information about the research study. The following is a detailed explanation of the structure of a research paper:

The title page contains the title of the paper, the name(s) of the author(s), and the affiliation(s) of the author(s). It also includes the date of submission and possibly, the name of the journal or conference where the paper is to be published.

The abstract is a brief summary of the research paper, typically ranging from 100 to 250 words. It should include the research question, the methods used, the key findings, and the implications of the results. The abstract should be written in a concise and clear manner to allow readers to quickly grasp the essence of the research.

Introduction

The introduction section of a research paper provides background information about the research problem, the research question, and the research objectives. It also outlines the significance of the research, the research gap that it aims to fill, and the approach taken to address the research question. Finally, the introduction section ends with a clear statement of the research hypothesis or research question.

Literature Review

The literature review section of a research paper provides an overview of the existing literature on the topic of study. It includes a critical analysis and synthesis of the literature, highlighting the key concepts, themes, and debates. The literature review should also demonstrate the research gap and how the current study seeks to address it.

The methods section of a research paper describes the research design, the sample selection, the data collection and analysis procedures, and the statistical methods used to analyze the data. This section should provide sufficient detail for other researchers to replicate the study.

The results section presents the findings of the research, using tables, graphs, and figures to illustrate the data. The findings should be presented in a clear and concise manner, with reference to the research question and hypothesis.

The discussion section of a research paper interprets the findings and discusses their implications for the research question, the literature review, and the field of study. It should also address the limitations of the study and suggest future research directions.

The conclusion section summarizes the main findings of the study, restates the research question and hypothesis, and provides a final reflection on the significance of the research.

The references section provides a list of all the sources cited in the paper, following a specific citation style such as APA, MLA or Chicago.

How to Write Research Paper

You can write Research Paper by the following guide:

- Choose a Topic: The first step is to select a topic that interests you and is relevant to your field of study. Brainstorm ideas and narrow down to a research question that is specific and researchable.

- Conduct a Literature Review: The literature review helps you identify the gap in the existing research and provides a basis for your research question. It also helps you to develop a theoretical framework and research hypothesis.

- Develop a Thesis Statement : The thesis statement is the main argument of your research paper. It should be clear, concise and specific to your research question.

- Plan your Research: Develop a research plan that outlines the methods, data sources, and data analysis procedures. This will help you to collect and analyze data effectively.

- Collect and Analyze Data: Collect data using various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments. Analyze data using statistical tools or other qualitative methods.

- Organize your Paper : Organize your paper into sections such as Introduction, Literature Review, Methods, Results, Discussion, and Conclusion. Ensure that each section is coherent and follows a logical flow.

- Write your Paper : Start by writing the introduction, followed by the literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. Ensure that your writing is clear, concise, and follows the required formatting and citation styles.

- Edit and Proofread your Paper: Review your paper for grammar and spelling errors, and ensure that it is well-structured and easy to read. Ask someone else to review your paper to get feedback and suggestions for improvement.

- Cite your Sources: Ensure that you properly cite all sources used in your research paper. This is essential for giving credit to the original authors and avoiding plagiarism.

Research Paper Example

Note : The below example research paper is for illustrative purposes only and is not an actual research paper. Actual research papers may have different structures, contents, and formats depending on the field of study, research question, data collection and analysis methods, and other factors. Students should always consult with their professors or supervisors for specific guidelines and expectations for their research papers.

Research Paper Example sample for Students:

Title: The Impact of Social Media on Mental Health among Young Adults

Abstract: This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults. A literature review was conducted to examine the existing research on the topic. A survey was then administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Introduction: Social media has become an integral part of modern life, particularly among young adults. While social media has many benefits, including increased communication and social connectivity, it has also been associated with negative outcomes, such as addiction, cyberbullying, and mental health problems. This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults.

Literature Review: The literature review highlights the existing research on the impact of social media use on mental health. The review shows that social media use is associated with depression, anxiety, stress, and other mental health problems. The review also identifies the factors that contribute to the negative impact of social media, including social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Methods : A survey was administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The survey included questions on social media use, mental health status (measured using the DASS-21), and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and regression analysis.

Results : The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Discussion : The study’s findings suggest that social media use has a negative impact on the mental health of young adults. The study highlights the need for interventions that address the factors contributing to the negative impact of social media, such as social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Conclusion : In conclusion, social media use has a significant impact on the mental health of young adults. The study’s findings underscore the need for interventions that promote healthy social media use and address the negative outcomes associated with social media use. Future research can explore the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health. Additionally, longitudinal studies can investigate the long-term effects of social media use on mental health.

Limitations : The study has some limitations, including the use of self-report measures and a cross-sectional design. The use of self-report measures may result in biased responses, and a cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causality.

Implications: The study’s findings have implications for mental health professionals, educators, and policymakers. Mental health professionals can use the findings to develop interventions that address the negative impact of social media use on mental health. Educators can incorporate social media literacy into their curriculum to promote healthy social media use among young adults. Policymakers can use the findings to develop policies that protect young adults from the negative outcomes associated with social media use.

References :

- Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2019). Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Preventive medicine reports, 15, 100918.

- Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Barrett, E. L., Sidani, J. E., Colditz, J. B., … & James, A. E. (2017). Use of multiple social media platforms and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A nationally-representative study among US young adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 1-9.

- Van der Meer, T. G., & Verhoeven, J. W. (2017). Social media and its impact on academic performance of students. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 16, 383-398.

Appendix : The survey used in this study is provided below.

Social Media and Mental Health Survey

- How often do you use social media per day?

- Less than 30 minutes

- 30 minutes to 1 hour

- 1 to 2 hours

- 2 to 4 hours

- More than 4 hours

- Which social media platforms do you use?

- Others (Please specify)

- How often do you experience the following on social media?

- Social comparison (comparing yourself to others)

- Cyberbullying

- Fear of Missing Out (FOMO)

- Have you ever experienced any of the following mental health problems in the past month?

- Do you think social media use has a positive or negative impact on your mental health?

- Very positive

- Somewhat positive

- Somewhat negative

- Very negative

- In your opinion, which factors contribute to the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Social comparison

- In your opinion, what interventions could be effective in reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Education on healthy social media use

- Counseling for mental health problems caused by social media

- Social media detox programs

- Regulation of social media use

Thank you for your participation!

Applications of Research Paper

Research papers have several applications in various fields, including:

- Advancing knowledge: Research papers contribute to the advancement of knowledge by generating new insights, theories, and findings that can inform future research and practice. They help to answer important questions, clarify existing knowledge, and identify areas that require further investigation.

- Informing policy: Research papers can inform policy decisions by providing evidence-based recommendations for policymakers. They can help to identify gaps in current policies, evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, and inform the development of new policies and regulations.

- Improving practice: Research papers can improve practice by providing evidence-based guidance for professionals in various fields, including medicine, education, business, and psychology. They can inform the development of best practices, guidelines, and standards of care that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- Educating students : Research papers are often used as teaching tools in universities and colleges to educate students about research methods, data analysis, and academic writing. They help students to develop critical thinking skills, research skills, and communication skills that are essential for success in many careers.

- Fostering collaboration: Research papers can foster collaboration among researchers, practitioners, and policymakers by providing a platform for sharing knowledge and ideas. They can facilitate interdisciplinary collaborations and partnerships that can lead to innovative solutions to complex problems.

When to Write Research Paper

Research papers are typically written when a person has completed a research project or when they have conducted a study and have obtained data or findings that they want to share with the academic or professional community. Research papers are usually written in academic settings, such as universities, but they can also be written in professional settings, such as research organizations, government agencies, or private companies.

Here are some common situations where a person might need to write a research paper:

- For academic purposes: Students in universities and colleges are often required to write research papers as part of their coursework, particularly in the social sciences, natural sciences, and humanities. Writing research papers helps students to develop research skills, critical thinking skills, and academic writing skills.

- For publication: Researchers often write research papers to publish their findings in academic journals or to present their work at academic conferences. Publishing research papers is an important way to disseminate research findings to the academic community and to establish oneself as an expert in a particular field.

- To inform policy or practice : Researchers may write research papers to inform policy decisions or to improve practice in various fields. Research findings can be used to inform the development of policies, guidelines, and best practices that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- To share new insights or ideas: Researchers may write research papers to share new insights or ideas with the academic or professional community. They may present new theories, propose new research methods, or challenge existing paradigms in their field.

Purpose of Research Paper

The purpose of a research paper is to present the results of a study or investigation in a clear, concise, and structured manner. Research papers are written to communicate new knowledge, ideas, or findings to a specific audience, such as researchers, scholars, practitioners, or policymakers. The primary purposes of a research paper are:

- To contribute to the body of knowledge : Research papers aim to add new knowledge or insights to a particular field or discipline. They do this by reporting the results of empirical studies, reviewing and synthesizing existing literature, proposing new theories, or providing new perspectives on a topic.

- To inform or persuade: Research papers are written to inform or persuade the reader about a particular issue, topic, or phenomenon. They present evidence and arguments to support their claims and seek to persuade the reader of the validity of their findings or recommendations.

- To advance the field: Research papers seek to advance the field or discipline by identifying gaps in knowledge, proposing new research questions or approaches, or challenging existing assumptions or paradigms. They aim to contribute to ongoing debates and discussions within a field and to stimulate further research and inquiry.

- To demonstrate research skills: Research papers demonstrate the author’s research skills, including their ability to design and conduct a study, collect and analyze data, and interpret and communicate findings. They also demonstrate the author’s ability to critically evaluate existing literature, synthesize information from multiple sources, and write in a clear and structured manner.

Characteristics of Research Paper

Research papers have several characteristics that distinguish them from other forms of academic or professional writing. Here are some common characteristics of research papers:

- Evidence-based: Research papers are based on empirical evidence, which is collected through rigorous research methods such as experiments, surveys, observations, or interviews. They rely on objective data and facts to support their claims and conclusions.

- Structured and organized: Research papers have a clear and logical structure, with sections such as introduction, literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. They are organized in a way that helps the reader to follow the argument and understand the findings.

- Formal and objective: Research papers are written in a formal and objective tone, with an emphasis on clarity, precision, and accuracy. They avoid subjective language or personal opinions and instead rely on objective data and analysis to support their arguments.

- Citations and references: Research papers include citations and references to acknowledge the sources of information and ideas used in the paper. They use a specific citation style, such as APA, MLA, or Chicago, to ensure consistency and accuracy.

- Peer-reviewed: Research papers are often peer-reviewed, which means they are evaluated by other experts in the field before they are published. Peer-review ensures that the research is of high quality, meets ethical standards, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

- Objective and unbiased: Research papers strive to be objective and unbiased in their presentation of the findings. They avoid personal biases or preconceptions and instead rely on the data and analysis to draw conclusions.

Advantages of Research Paper

Research papers have many advantages, both for the individual researcher and for the broader academic and professional community. Here are some advantages of research papers:

- Contribution to knowledge: Research papers contribute to the body of knowledge in a particular field or discipline. They add new information, insights, and perspectives to existing literature and help advance the understanding of a particular phenomenon or issue.

- Opportunity for intellectual growth: Research papers provide an opportunity for intellectual growth for the researcher. They require critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity, which can help develop the researcher’s skills and knowledge.

- Career advancement: Research papers can help advance the researcher’s career by demonstrating their expertise and contributions to the field. They can also lead to new research opportunities, collaborations, and funding.

- Academic recognition: Research papers can lead to academic recognition in the form of awards, grants, or invitations to speak at conferences or events. They can also contribute to the researcher’s reputation and standing in the field.

- Impact on policy and practice: Research papers can have a significant impact on policy and practice. They can inform policy decisions, guide practice, and lead to changes in laws, regulations, or procedures.

- Advancement of society: Research papers can contribute to the advancement of society by addressing important issues, identifying solutions to problems, and promoting social justice and equality.

Limitations of Research Paper

Research papers also have some limitations that should be considered when interpreting their findings or implications. Here are some common limitations of research papers:

- Limited generalizability: Research findings may not be generalizable to other populations, settings, or contexts. Studies often use specific samples or conditions that may not reflect the broader population or real-world situations.

- Potential for bias : Research papers may be biased due to factors such as sample selection, measurement errors, or researcher biases. It is important to evaluate the quality of the research design and methods used to ensure that the findings are valid and reliable.

- Ethical concerns: Research papers may raise ethical concerns, such as the use of vulnerable populations or invasive procedures. Researchers must adhere to ethical guidelines and obtain informed consent from participants to ensure that the research is conducted in a responsible and respectful manner.

- Limitations of methodology: Research papers may be limited by the methodology used to collect and analyze data. For example, certain research methods may not capture the complexity or nuance of a particular phenomenon, or may not be appropriate for certain research questions.

- Publication bias: Research papers may be subject to publication bias, where positive or significant findings are more likely to be published than negative or non-significant findings. This can skew the overall findings of a particular area of research.

- Time and resource constraints: Research papers may be limited by time and resource constraints, which can affect the quality and scope of the research. Researchers may not have access to certain data or resources, or may be unable to conduct long-term studies due to practical limitations.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Research Paper Conclusion – Writing Guide and...

Appendices – Writing Guide, Types and Examples

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Research Report – Example, Writing Guide and...

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Scope of the Research – Writing Guide and...

Join thousands of product people at Insight Out Conf on April 11. Register free.

Insights hub solutions

Analyze data

Uncover deep customer insights with fast, powerful features, store insights, curate and manage insights in one searchable platform, scale research, unlock the potential of customer insights at enterprise scale.

Featured reads

Tips and tricks

Make magic with your customer data in Dovetail

Four ways Dovetail helps Product Managers master continuous product discovery

Product updates

Dovetail retro: our biggest releases from the past year

Events and videos

© Dovetail Research Pty. Ltd.

- How to write a research paper

Last updated

11 January 2024

Reviewed by

With proper planning, knowledge, and framework, completing a research paper can be a fulfilling and exciting experience.

Though it might initially sound slightly intimidating, this guide will help you embrace the challenge.

By documenting your findings, you can inspire others and make a difference in your field. Here's how you can make your research paper unique and comprehensive.

- What is a research paper?

Research papers allow you to demonstrate your knowledge and understanding of a particular topic. These papers are usually lengthier and more detailed than typical essays, requiring deeper insight into the chosen topic.

To write a research paper, you must first choose a topic that interests you and is relevant to the field of study. Once you’ve selected your topic, gathering as many relevant resources as possible, including books, scholarly articles, credible websites, and other academic materials, is essential. You must then read and analyze these sources, summarizing their key points and identifying gaps in the current research.

You can formulate your ideas and opinions once you thoroughly understand the existing research. To get there might involve conducting original research, gathering data, or analyzing existing data sets. It could also involve presenting an original argument or interpretation of the existing research.

Writing a successful research paper involves presenting your findings clearly and engagingly, which might involve using charts, graphs, or other visual aids to present your data and using concise language to explain your findings. You must also ensure your paper adheres to relevant academic formatting guidelines, including proper citations and references.

Overall, writing a research paper requires a significant amount of time, effort, and attention to detail. However, it is also an enriching experience that allows you to delve deeply into a subject that interests you and contribute to the existing body of knowledge in your chosen field.

- How long should a research paper be?

Research papers are deep dives into a topic. Therefore, they tend to be longer pieces of work than essays or opinion pieces.

However, a suitable length depends on the complexity of the topic and your level of expertise. For instance, are you a first-year college student or an experienced professional?

Also, remember that the best research papers provide valuable information for the benefit of others. Therefore, the quality of information matters most, not necessarily the length. Being concise is valuable.

Following these best practice steps will help keep your process simple and productive:

1. Gaining a deep understanding of any expectations

Before diving into your intended topic or beginning the research phase, take some time to orient yourself. Suppose there’s a specific topic assigned to you. In that case, it’s essential to deeply understand the question and organize your planning and approach in response. Pay attention to the key requirements and ensure you align your writing accordingly.

This preparation step entails

Deeply understanding the task or assignment

Being clear about the expected format and length

Familiarizing yourself with the citation and referencing requirements

Understanding any defined limits for your research contribution

Where applicable, speaking to your professor or research supervisor for further clarification

2. Choose your research topic

Select a research topic that aligns with both your interests and available resources. Ideally, focus on a field where you possess significant experience and analytical skills. In crafting your research paper, it's crucial to go beyond summarizing existing data and contribute fresh insights to the chosen area.

Consider narrowing your focus to a specific aspect of the topic. For example, if exploring the link between technology and mental health, delve into how social media use during the pandemic impacts the well-being of college students. Conducting interviews and surveys with students could provide firsthand data and unique perspectives, adding substantial value to the existing knowledge.

When finalizing your topic, adhere to legal and ethical norms in the relevant area (this ensures the integrity of your research, protects participants' rights, upholds intellectual property standards, and ensures transparency and accountability). Following these principles not only maintains the credibility of your work but also builds trust within your academic or professional community.

For instance, in writing about medical research, consider legal and ethical norms, including patient confidentiality laws and informed consent requirements. Similarly, if analyzing user data on social media platforms, be mindful of data privacy regulations, ensuring compliance with laws governing personal information collection and use. Aligning with legal and ethical standards not only avoids potential issues but also underscores the responsible conduct of your research.

3. Gather preliminary research

Once you’ve landed on your topic, it’s time to explore it further. You’ll want to discover more about available resources and existing research relevant to your assignment at this stage.

This exploratory phase is vital as you may discover issues with your original idea or realize you have insufficient resources to explore the topic effectively. This key bit of groundwork allows you to redirect your research topic in a different, more feasible, or more relevant direction if necessary.

Spending ample time at this stage ensures you gather everything you need, learn as much as you can about the topic, and discover gaps where the topic has yet to be sufficiently covered, offering an opportunity to research it further.

4. Define your research question

To produce a well-structured and focused paper, it is imperative to formulate a clear and precise research question that will guide your work. Your research question must be informed by the existing literature and tailored to the scope and objectives of your project. By refining your focus, you can produce a thoughtful and engaging paper that effectively communicates your ideas to your readers.

5. Write a thesis statement

A thesis statement is a one-to-two-sentence summary of your research paper's main argument or direction. It serves as an overall guide to summarize the overall intent of the research paper for you and anyone wanting to know more about the research.

A strong thesis statement is:

Concise and clear: Explain your case in simple sentences (avoid covering multiple ideas). It might help to think of this section as an elevator pitch.

Specific: Ensure that there is no ambiguity in your statement and that your summary covers the points argued in the paper.

Debatable: A thesis statement puts forward a specific argument––it is not merely a statement but a debatable point that can be analyzed and discussed.

Here are three thesis statement examples from different disciplines:

Psychology thesis example: "We're studying adults aged 25-40 to see if taking short breaks for mindfulness can help with stress. Our goal is to find practical ways to manage anxiety better."

Environmental science thesis example: "This research paper looks into how having more city parks might make the air cleaner and keep people healthier. I want to find out if more green spaces means breathing fewer carcinogens in big cities."

UX research thesis example: "This study focuses on improving mobile banking for older adults using ethnographic research, eye-tracking analysis, and interactive prototyping. We investigate the usefulness of eye-tracking analysis with older individuals, aiming to spark debate and offer fresh perspectives on UX design and digital inclusivity for the aging population."

6. Conduct in-depth research

A research paper doesn’t just include research that you’ve uncovered from other papers and studies but your fresh insights, too. You will seek to become an expert on your topic––understanding the nuances in the current leading theories. You will analyze existing research and add your thinking and discoveries. It's crucial to conduct well-designed research that is rigorous, robust, and based on reliable sources. Suppose a research paper lacks evidence or is biased. In that case, it won't benefit the academic community or the general public. Therefore, examining the topic thoroughly and furthering its understanding through high-quality research is essential. That usually means conducting new research. Depending on the area under investigation, you may conduct surveys, interviews, diary studies, or observational research to uncover new insights or bolster current claims.

7. Determine supporting evidence

Not every piece of research you’ve discovered will be relevant to your research paper. It’s important to categorize the most meaningful evidence to include alongside your discoveries. It's important to include evidence that doesn't support your claims to avoid exclusion bias and ensure a fair research paper.

8. Write a research paper outline

Before diving in and writing the whole paper, start with an outline. It will help you to see if more research is needed, and it will provide a framework by which to write a more compelling paper. Your supervisor may even request an outline to approve before beginning to write the first draft of the full paper. An outline will include your topic, thesis statement, key headings, short summaries of the research, and your arguments.

9. Write your first draft

Once you feel confident about your outline and sources, it’s time to write your first draft. While penning a long piece of content can be intimidating, if you’ve laid the groundwork, you will have a structure to help you move steadily through each section. To keep up motivation and inspiration, it’s often best to keep the pace quick. Stopping for long periods can interrupt your flow and make jumping back in harder than writing when things are fresh in your mind.

10. Cite your sources correctly

It's always a good practice to give credit where it's due, and the same goes for citing any works that have influenced your paper. Building your arguments on credible references adds value and authenticity to your research. In the formatting guidelines section, you’ll find an overview of different citation styles (MLA, CMOS, or APA), which will help you meet any publishing or academic requirements and strengthen your paper's credibility. It is essential to follow the guidelines provided by your school or the publication you are submitting to ensure the accuracy and relevance of your citations.

11. Ensure your work is original

It is crucial to ensure the originality of your paper, as plagiarism can lead to serious consequences. To avoid plagiarism, you should use proper paraphrasing and quoting techniques. Paraphrasing is rewriting a text in your own words while maintaining the original meaning. Quoting involves directly citing the source. Giving credit to the original author or source is essential whenever you borrow their ideas or words. You can also use plagiarism detection tools such as Scribbr or Grammarly to check the originality of your paper. These tools compare your draft writing to a vast database of online sources. If you find any accidental plagiarism, you should correct it immediately by rephrasing or citing the source.

12. Revise, edit, and proofread

One of the essential qualities of excellent writers is their ability to understand the importance of editing and proofreading. Even though it's tempting to call it a day once you've finished your writing, editing your work can significantly improve its quality. It's natural to overlook the weaker areas when you've just finished writing a paper. Therefore, it's best to take a break of a day or two, or even up to a week, to refresh your mind. This way, you can return to your work with a new perspective. After some breathing room, you can spot any inconsistencies, spelling and grammar errors, typos, or missing citations and correct them.

- The best research paper format

The format of your research paper should align with the requirements set forth by your college, school, or target publication.

There is no one “best” format, per se. Depending on the stated requirements, you may need to include the following elements:

Title page: The title page of a research paper typically includes the title, author's name, and institutional affiliation and may include additional information such as a course name or instructor's name.

Table of contents: Include a table of contents to make it easy for readers to find specific sections of your paper.

Abstract: The abstract is a summary of the purpose of the paper.

Methods : In this section, describe the research methods used. This may include collecting data, conducting interviews, or doing field research.

Results: Summarize the conclusions you drew from your research in this section.

Discussion: In this section, discuss the implications of your research. Be sure to mention any significant limitations to your approach and suggest areas for further research.

Tables, charts, and illustrations: Use tables, charts, and illustrations to help convey your research findings and make them easier to understand.

Works cited or reference page: Include a works cited or reference page to give credit to the sources that you used to conduct your research.

Bibliography: Provide a list of all the sources you consulted while conducting your research.

Dedication and acknowledgments : Optionally, you may include a dedication and acknowledgments section to thank individuals who helped you with your research.

- General style and formatting guidelines

Formatting your research paper means you can submit it to your college, journal, or other publications in compliance with their criteria.

Research papers tend to follow the American Psychological Association (APA), Modern Language Association (MLA), or Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS) guidelines.

Here’s how each style guide is typically used:

Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS):

CMOS is a versatile style guide used for various types of writing. It's known for its flexibility and use in the humanities. CMOS provides guidelines for citations, formatting, and overall writing style. It allows for both footnotes and in-text citations, giving writers options based on their preferences or publication requirements.

American Psychological Association (APA):

APA is common in the social sciences. It’s hailed for its clarity and emphasis on precision. It has specific rules for citing sources, creating references, and formatting papers. APA style uses in-text citations with an accompanying reference list. It's designed to convey information efficiently and is widely used in academic and scientific writing.

Modern Language Association (MLA):

MLA is widely used in the humanities, especially literature and language studies. It emphasizes the author-page format for in-text citations and provides guidelines for creating a "Works Cited" page. MLA is known for its focus on the author's name and the literary works cited. It’s frequently used in disciplines that prioritize literary analysis and critical thinking.

To confirm you're using the latest style guide, check the official website or publisher's site for updates, consult academic resources, and verify the guide's publication date. Online platforms and educational resources may also provide summaries and alerts about any revisions or additions to the style guide.

Citing sources

When working on your research paper, it's important to cite the sources you used properly. Your citation style will guide you through this process. Generally, there are three parts to citing sources in your research paper:

First, provide a brief citation in the body of your essay. This is also known as a parenthetical or in-text citation.

Second, include a full citation in the Reference list at the end of your paper. Different types of citations include in-text citations, footnotes, and reference lists.

In-text citations include the author's surname and the date of the citation.

Footnotes appear at the bottom of each page of your research paper. They may also be summarized within a reference list at the end of the paper.

A reference list includes all of the research used within the paper at the end of the document. It should include the author, date, paper title, and publisher listed in the order that aligns with your citation style.

10 research paper writing tips:

Following some best practices is essential to writing a research paper that contributes to your field of study and creates a positive impact.

These tactics will help you structure your argument effectively and ensure your work benefits others:

Clear and precise language: Ensure your language is unambiguous. Use academic language appropriately, but keep it simple. Also, provide clear takeaways for your audience.

Effective idea separation: Organize the vast amount of information and sources in your paper with paragraphs and titles. Create easily digestible sections for your readers to navigate through.

Compelling intro: Craft an engaging introduction that captures your reader's interest. Hook your audience and motivate them to continue reading.

Thorough revision and editing: Take the time to review and edit your paper comprehensively. Use tools like Grammarly to detect and correct small, overlooked errors.

Thesis precision: Develop a clear and concise thesis statement that guides your paper. Ensure that your thesis aligns with your research's overall purpose and contribution.

Logical flow of ideas: Maintain a logical progression throughout the paper. Use transitions effectively to connect different sections and maintain coherence.

Critical evaluation of sources: Evaluate and critically assess the relevance and reliability of your sources. Ensure that your research is based on credible and up-to-date information.

Thematic consistency: Maintain a consistent theme throughout the paper. Ensure that all sections contribute cohesively to the overall argument.

Relevant supporting evidence: Provide concise and relevant evidence to support your arguments. Avoid unnecessary details that may distract from the main points.

Embrace counterarguments: Acknowledge and address opposing views to strengthen your position. Show that you have considered alternative arguments in your field.

7 research tips

If you want your paper to not only be well-written but also contribute to the progress of human knowledge, consider these tips to take your paper to the next level:

Selecting the appropriate topic: The topic you select should align with your area of expertise, comply with the requirements of your project, and have sufficient resources for a comprehensive investigation.

Use academic databases: Academic databases such as PubMed, Google Scholar, and JSTOR offer a wealth of research papers that can help you discover everything you need to know about your chosen topic.

Critically evaluate sources: It is important not to accept research findings at face value. Instead, it is crucial to critically analyze the information to avoid jumping to conclusions or overlooking important details. A well-written research paper requires a critical analysis with thorough reasoning to support claims.

Diversify your sources: Expand your research horizons by exploring a variety of sources beyond the standard databases. Utilize books, conference proceedings, and interviews to gather diverse perspectives and enrich your understanding of the topic.

Take detailed notes: Detailed note-taking is crucial during research and can help you form the outline and body of your paper.

Stay up on trends: Keep abreast of the latest developments in your field by regularly checking for recent publications. Subscribe to newsletters, follow relevant journals, and attend conferences to stay informed about emerging trends and advancements.

Engage in peer review: Seek feedback from peers or mentors to ensure the rigor and validity of your research. Peer review helps identify potential weaknesses in your methodology and strengthens the overall credibility of your findings.

- The real-world impact of research papers

Writing a research paper is more than an academic or business exercise. The experience provides an opportunity to explore a subject in-depth, broaden one's understanding, and arrive at meaningful conclusions. With careful planning, dedication, and hard work, writing a research paper can be a fulfilling and enriching experience contributing to advancing knowledge.

How do I publish my research paper?

Many academics wish to publish their research papers. While challenging, your paper might get traction if it covers new and well-written information. To publish your research paper, find a target publication, thoroughly read their guidelines, format your paper accordingly, and send it to them per their instructions. You may need to include a cover letter, too. After submission, your paper may be peer-reviewed by experts to assess its legitimacy, quality, originality, and methodology. Following review, you will be informed by the publication whether they have accepted or rejected your paper.

What is a good opening sentence for a research paper?

Beginning your research paper with a compelling introduction can ensure readers are interested in going further. A relevant quote, a compelling statistic, or a bold argument can start the paper and hook your reader. Remember, though, that the most important aspect of a research paper is the quality of the information––not necessarily your ability to storytell, so ensure anything you write aligns with your goals.

Research paper vs. a research proposal—what’s the difference?

While some may confuse research papers and proposals, they are different documents.

A research proposal comes before a research paper. It is a detailed document that outlines an intended area of exploration. It includes the research topic, methodology, timeline, sources, and potential conclusions. Research proposals are often required when seeking approval to conduct research.

A research paper is a summary of research findings. A research paper follows a structured format to present those findings and construct an argument or conclusion.

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 17 February 2024

Last updated: 19 November 2023

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics.

- 10 research paper

Log in or sign up

Get started for free

Module 5: Writing the Research Paper and Acknowledging Your Sources

Introduction to writing the research paper and acknowledging your sources.

When you write a research paper, the success of your work can depend almost as heavily on the work of others as it does on your own efforts. Your information sources not only provide essential facts and insights that can enhance and clarify your original ideas, source material can help you better understand your own theories and opinions and help you to arrive at more authoritative, clearly drawn conclusions.

Because of the debt that you, as the author of a research paper, owe to your sources, it is essential that you understand how to present, acknowledge, and document the sources that you have built into your work. You should be aware that using accepted standards of style and citation can benefit you as a writer as well. When your references are clearly annotated within your work, you can see where your source material appears, making it that much easier to edit, update, and expand your work.

By following accepted standards to present your work in a manner that is accessible to readers, you also enhance your credibility as a writer and researcher. When your readers can easily identify and check your sources, they are more likely to accept you as a member of their discourse communities. This is especially important in an academic environment, where your readers are likely to investigate your work as a potential source for their own research projects. To put it bluntly, careful adherence to accepted style conventions in academic writing can mean the difference between great success and total failure.

In this unit, we will review the concept of plagiarism and discuss how you can use clear, consistent documentation to avoid even the unintentional misuse of source material. We will also review many of the commonly accepted methods of acknowledging and documenting sources used in writing college research papers. We will pay particular attention to the Modern Language Association (MLA) style standards, because this is the most widely used convention in college undergraduate work.

This unit will culminate in an opportunity to build your selected source material into a fully developed first draft of your final research paper. By the time you have finished the final activity in this unit, you should have accomplished much of the groundwork for your final research paper.

By the time you have finished the work in this unit, you should have a command of the materials and techniques you will need to complete a well-developed academic paper. As a by-product, your final research paper for this course will probably be nearly finished.

The final activity in this unit is to develop a final polished and clearly documented research paper that makes full use of the tools, techniques, and products that you have discovered, developed, and organized during the preceding four units.

- ENGL002: English Composition II. Provided by : Saylor Academy. Located at : http://www.saylor.org/courses/engl002/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Clerc Center | PK-12 & Outreach

- KDES | PK-8th Grade School (D.C. Metro Area)

- MSSD | 9th-12th Grade School (Nationwide)

- Gallaudet University Regional Centers

- Parent Advocacy App

- K-12 ASL Content Standards

- National Resources

- Youth Programs

- Academic Bowl

- Battle Of The Books

- National Literary Competition

- Youth Debate Bowl

- Bison Sports Camp

- Discover College and Careers (DC²)

- Financial Wizards

- Immerse Into ASL

- Alumni Relations

- Alumni Association

- Homecoming Weekend

- Class Giving

- Get Tickets / BisonPass

- Sport Calendars

- Cross Country

- Swimming & Diving

- Track & Field

- Indoor Track & Field

- Cheerleading

- Winter Cheerleading

- Human Resources

- Plan a Visit

- Request Info

- Areas of Study

- Accessible Human-Centered Computing

- American Sign Language

- Art and Media Design

- Communication Studies

- Data Science

- Deaf Studies

- Early Intervention Studies Graduate Programs

- Educational Neuroscience

- Hearing, Speech, and Language Sciences

- Information Technology

- International Development

- Interpretation and Translation

- Linguistics

- Mathematics

- Philosophy and Religion

- Physical Education & Recreation

- Public Affairs

- Public Health

- Sexuality and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Theatre and Dance

- World Languages and Cultures

- B.A. in American Sign Language

- B.A. in Art and Media Design

- B.A. in Biology

- B.A. in Communication Studies

- B.A. in Communication Studies for Online Degree Completion Program

- B.A. in Deaf Studies

- B.A. in Deaf Studies for Online Degree Completion Program

- B.A. in Education with a Specialization in Early Childhood Education

- B.A. in Education with a Specialization in Elementary Education

- B.A. in English

- B.A. in Government

- B.A. in Government with a Specialization in Law

- B.A. in History

- B.A. in Interdisciplinary Spanish

- B.A. in International Studies

- B.A. in Interpretation

- B.A. in Mathematics

- B.A. in Philosophy

- B.A. in Psychology

- B.A. in Psychology for Online Degree Completion Program

- B.A. in Social Work (BSW)

- B.A. in Sociology

- B.A. in Sociology with a concentration in Criminology

- B.A. in Theatre Arts: Production/Performance

- B.A. or B.S. in Education with a Specialization in Secondary Education: Science, English, Mathematics or Social Studies

- B.S in Risk Management and Insurance

- B.S. in Accounting

- B.S. in Biology

- B.S. in Business Administration

- B.S. in Information Technology

- B.S. in Mathematics

- B.S. in Physical Education and Recreation

- B.S. In Public Health

- General Education

- Honors Program

- Peace Corps Prep program

- Self-Directed Major

- M.A. in Counseling: Clinical Mental Health Counseling

- M.A. in Counseling: School Counseling

- M.A. in Deaf Education

- M.A. in Deaf Education Studies

- M.A. in Deaf Studies: Cultural Studies

- M.A. in Deaf Studies: Language and Human Rights

- M.A. in Early Childhood Education and Deaf Education

- M.A. in Early Intervention Studies

- M.A. in Elementary Education and Deaf Education

- M.A. in International Development

- M.A. in Interpretation: Combined Interpreting Practice and Research

- M.A. in Interpretation: Interpreting Research

- M.A. in Linguistics

- M.A. in Secondary Education and Deaf Education

- M.A. in Sign Language Education

- M.S. in Accessible Human-Centered Computing

- M.S. in Speech-Language Pathology

- Master of Social Work (MSW)

- Au.D. in Audiology

- Ed.D. in Transformational Leadership and Administration in Deaf Education

- Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology

- Ph.D. in Critical Studies in the Education of Deaf Learners

- Ph.D. in Hearing, Speech, and Language Sciences

- Ph.D. in Linguistics

- Ph.D. in Translation and Interpreting Studies

- Ph.D. Program in Educational Neuroscience (PEN)

- Individual Courses and Training

- Certificates

- Certificate in Sexuality and Gender Studies

- Educating Deaf Students with Disabilities (online, post-bachelor’s)

- American Sign Language and English Bilingual Early Childhood Deaf Education: Birth to 5 (online, post-bachelor’s)

- Peer Mentor Training (low-residency/hybrid, post-bachelor’s)

- Early Intervention Studies Graduate Certificate

- Online Degree Programs

- ODCP Minor in Communication Studies

- ODCP Minor in Deaf Studies

- ODCP Minor in Psychology

- ODCP Minor in Writing

- Online Degree Program General Education Curriculum

- University Capstone Honors for Online Degree Completion Program

Quick Links

- PK-12 & Outreach

- NSO Schedule

The Process of Writing a Research Paper

202.448-7036

Planning the Research Paper

The goal of a research paper is to bring together different views, evidence, and facts about a topic from books, articles, and interviews, then interpret the information into your writing. It’s about a relationship between you, other writers, and your teacher/audience.

A research paper will show two things: what you know or learned about a certain topic, and what other people know about the same topic. Often you make a judgment, or just explain complex ideas to the reader. The length of the research paper depends on your teacher’s guidelines. It’s always a good idea to keep your teacher in mind while writing your paper because the teacher is your audience.

The Process There are three stages for doing a research paper. These stages are:

While most people start with prewriting, the three stages of the writing process overlap. Writing is not the kind of process where you have to finish step one before moving on to step two, and so on. Your job is to make your ideas as clear as possible for the reader, and that means you might have to go back and forth between the prewriting, writing and revising stages several times before submitting the paper.

» Prewriting Thinking about a topic

The first thing you should do when starting your research paper is to think of a topic. Try to pick a topic that interests you and your teacher — interesting topics are easier to write about than boring topics! Make sure that your topic is not too hard to research, and that there is enough material on the topic. Talk to as many people as possible about your topic, especially your teacher. You’ll be surprised at the ideas you’ll get from talking about your topic. Be sure to always discuss potential topics with your teacher.

Places you can find a topic: newspapers, magazines, television news, the World Wide Web, and even in the index of a textbook!

Narrowing down your topic

As you think about your topic and start reading, you should begin thinking about a possible thesis statement (a sentence or two explaining your opinion about the topic). One technique is to ask yourself one important question about your topic, and as you find your answer, the thesis can develop from that. Some other techniques you may use to narrow your topic are: jot lists; preliminary outlines; listing possible thesis statements; listing questions; and/or making a concept map. It also may be helpful to have a friend ask you questions about your topic.

For help on developing your thesis statement, see the English Center Guide to Developing a Thesis Statement .

Discovery/Reading about your topic

You need to find information that helps you support your thesis. There are different places you can find this information: books, articles, people (interviews), and the internet.

As you gather the information or ideas you need, you need to make sure that you take notes and write down where and who you got the information from. This is called “citing your sources.” If you write your paper using information from other writers and do not cite the sources, you are committing plagiarism . If you plagiarize, you can get an “F” on your paper, fail the course, or even get kicked out of school.

CITING SOURCES

There are three major different formats for citing sources. They are: the Modern Language Association (MLA) , the American Psychology Association (APA) , and the Chicago Turabian style . Always ask your teacher which format to use. For more information on these styles, see our other handouts!

ORGANIZING INFORMATION

After you’ve thought, read, and taken notes on your topic, you may want to revise your thesis because a good thesis will help you develop a plan for writing your paper. One way you can do this is to brainstorm — think about everything you know about your topic, and put it down on paper. Once you have it all written down, you can look it over and decide if you should change your thesis statement or not.

If you already developed a preliminary map or outline, now is the time to go back and revise it. If you haven’t developed a map or outline yet, now is the time to do it. The outline or concept map should help you organize how you want to present information to your readers. The clearer your outline or map, the easier it will be for you to write the paper. Be sure that each part of your outline supports your thesis. If it does not, you may want to change/revise your thesis statement again.

» Writing a research paper follows a standard compositional (essay) format. It has a title, introduction, body and conclusion. Some people like to start their research papers with a title and introduction, while others wait until they’ve already started the body of the paper before developing a title and introduction. See this link for more information about writing introductions and conclusions .

Some techniques that may help you with writing your paper are:

- start by writing your thesis statement

- use a free writing technique (What I mean is…)

- follow your outline or map

- pretend you are writing a letter to a friend, and tell them what you know about your topic

- follow your topic notecards

If you’re having difficulties thinking of what to write about next, you can look back at your notes that you have from when you were brainstorming for your topic.

» Revising The last (but not least) step is revising. When you are revising, look over your paper and make changes in weak areas. The different areas to look for mistakes include: content– too much detail, or too little detail; organization/structure (which is the order in which you write information about your topic); grammar; punctuation; capitalization; word choice; and citations.

It probably is best if you focus on the “big picture” first. The “big picture” means the organization (paragraph order), and content (ideas and points) of the paper. It also might help to go through your paper paragraph by paragraph and see if the main idea of each paragraph relates to the thesis. Be sure to keep an eye out for any repeated information (one of the most common mistakes made by students is having two or more paragraphs with the same information). Often good writers combine several paragraphs into one so they do not repeat information.

Revision Guidelines

- The audience understands your paper.

- The sentences are clear and complete.

- All paragraphs relate to the thesis.

- Each paragraph explains its purpose clearly.

- You do not repeat large blocks of information in two or more different paragraphs.

- The information in your paper is accurate.

- A friend or classmate has read through your paper and offered suggestions.

After you are satisfied with the content and structure of the paper, you then can focus on common errors like grammar, spelling, sentence structure, punctuation, capitalization, typos, and word choice.

Proofreading Guidelines

- Subjects and verbs agree.

- Verb tenses are consistent.

- Pronouns agree with the subjects they substitute.

- Word choices are clear.

- Capitalization is correct.

- Spelling is correct.

- Punctuation is correct.

- References are cited properly.

For more information on proofreading, see the English Center Punctuation and Grammar Review .

After writing the paper, it might help if you put it aside and do not look at it for a day or two. When you look at your paper again, you will see it with new eyes and notice mistakes you didn’t before. It’s a really good idea to ask someone else to read your paper before you submit it to your teacher. Good writers often get feedback and revise their paper several times before submitting it to the teacher.

Source: “Process of Writing a Research Paper,” by Ellen Beck and Rachel Mingo with contributions from Jules Nelson Hill and Vivion Smith, is based on the previous version by Dawn Taylor, Sharon Quintero, Robert Rich, Robert McDonald, and Katherine Eckhart.

202-448-7036

At a Glance

- Quick Facts

- University Leadership

- History & Traditions

- Accreditation

- Consumer Information

- Our 10-Year Vision: The Gallaudet Promise

- Annual Report of Achievements (ARA)

- The Signing Ecosystem

- Not Your Average University

Our Community

- Library & Archives

- Technology Support

- Interpreting Requests

- Ombuds Support

- Health and Wellness Programs

- Profile & Web Edits

Visit Gallaudet

- Explore Our Campus

- Virtual Tour

- Maps & Directions

- Shuttle Bus Schedule

- Kellogg Conference Hotel

- Welcome Center

- National Deaf Life Museum

- Apple Guide Maps

Engage Today

- Work at Gallaudet / Clerc Center

- Social Media Channels

- University Wide Events

- Sponsorship Requests

- Data Requests

- Media Inquiries

- Gallaudet Today Magazine

- Giving at Gallaudet

- Financial Aid

- Registrar’s Office

- Residence Life & Housing

- Safety & Security

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Graduate Admissions

- University Communications

- Clerc Center

Gallaudet University, chartered in 1864, is a private university for deaf and hard of hearing students.

Copyright © 2024 Gallaudet University. All rights reserved.

- Accessibility

- Cookie Consent Notice

- Privacy Policy

- File a Report

800 Florida Avenue NE, Washington, D.C. 20002

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

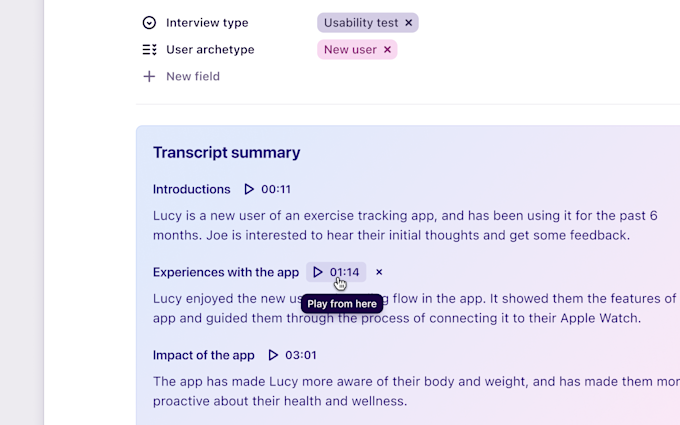

Writing a Research Paper Introduction | Step-by-Step Guide

Published on September 24, 2022 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on March 27, 2023.

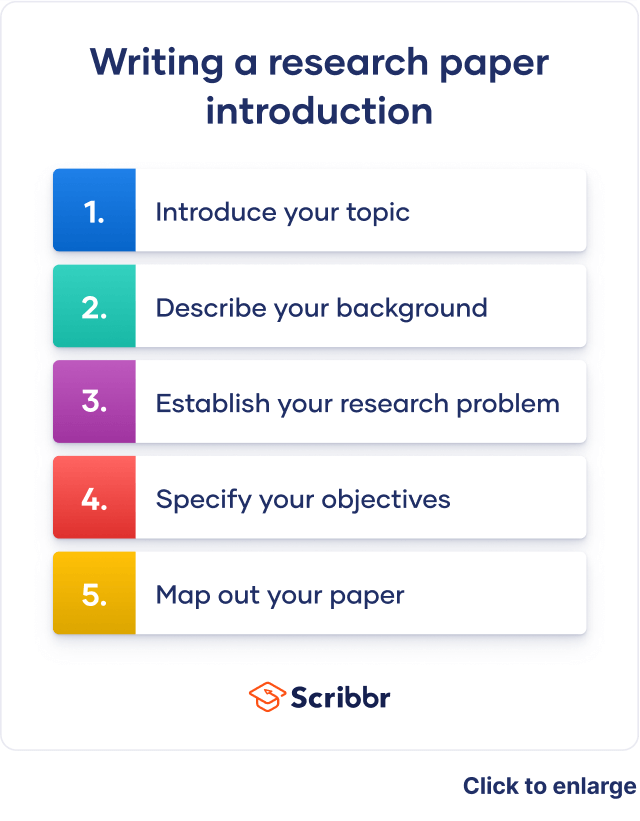

The introduction to a research paper is where you set up your topic and approach for the reader. It has several key goals:

- Present your topic and get the reader interested

- Provide background or summarize existing research

- Position your own approach

- Detail your specific research problem and problem statement

- Give an overview of the paper’s structure

The introduction looks slightly different depending on whether your paper presents the results of original empirical research or constructs an argument by engaging with a variety of sources.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: introduce your topic, step 2: describe the background, step 3: establish your research problem, step 4: specify your objective(s), step 5: map out your paper, research paper introduction examples, frequently asked questions about the research paper introduction.

The first job of the introduction is to tell the reader what your topic is and why it’s interesting or important. This is generally accomplished with a strong opening hook.

The hook is a striking opening sentence that clearly conveys the relevance of your topic. Think of an interesting fact or statistic, a strong statement, a question, or a brief anecdote that will get the reader wondering about your topic.

For example, the following could be an effective hook for an argumentative paper about the environmental impact of cattle farming:

A more empirical paper investigating the relationship of Instagram use with body image issues in adolescent girls might use the following hook:

Don’t feel that your hook necessarily has to be deeply impressive or creative. Clarity and relevance are still more important than catchiness. The key thing is to guide the reader into your topic and situate your ideas.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

This part of the introduction differs depending on what approach your paper is taking.

In a more argumentative paper, you’ll explore some general background here. In a more empirical paper, this is the place to review previous research and establish how yours fits in.

Argumentative paper: Background information

After you’ve caught your reader’s attention, specify a bit more, providing context and narrowing down your topic.

Provide only the most relevant background information. The introduction isn’t the place to get too in-depth; if more background is essential to your paper, it can appear in the body .

Empirical paper: Describing previous research

For a paper describing original research, you’ll instead provide an overview of the most relevant research that has already been conducted. This is a sort of miniature literature review —a sketch of the current state of research into your topic, boiled down to a few sentences.

This should be informed by genuine engagement with the literature. Your search can be less extensive than in a full literature review, but a clear sense of the relevant research is crucial to inform your own work.

Begin by establishing the kinds of research that have been done, and end with limitations or gaps in the research that you intend to respond to.

The next step is to clarify how your own research fits in and what problem it addresses.

Argumentative paper: Emphasize importance

In an argumentative research paper, you can simply state the problem you intend to discuss, and what is original or important about your argument.

Empirical paper: Relate to the literature

In an empirical research paper, try to lead into the problem on the basis of your discussion of the literature. Think in terms of these questions:

- What research gap is your work intended to fill?

- What limitations in previous work does it address?

- What contribution to knowledge does it make?

You can make the connection between your problem and the existing research using phrases like the following.

Now you’ll get into the specifics of what you intend to find out or express in your research paper.

The way you frame your research objectives varies. An argumentative paper presents a thesis statement, while an empirical paper generally poses a research question (sometimes with a hypothesis as to the answer).

Argumentative paper: Thesis statement

The thesis statement expresses the position that the rest of the paper will present evidence and arguments for. It can be presented in one or two sentences, and should state your position clearly and directly, without providing specific arguments for it at this point.

Empirical paper: Research question and hypothesis

The research question is the question you want to answer in an empirical research paper.

Present your research question clearly and directly, with a minimum of discussion at this point. The rest of the paper will be taken up with discussing and investigating this question; here you just need to express it.

A research question can be framed either directly or indirectly.

- This study set out to answer the following question: What effects does daily use of Instagram have on the prevalence of body image issues among adolescent girls?

- We investigated the effects of daily Instagram use on the prevalence of body image issues among adolescent girls.

If your research involved testing hypotheses , these should be stated along with your research question. They are usually presented in the past tense, since the hypothesis will already have been tested by the time you are writing up your paper.

For example, the following hypothesis might respond to the research question above:

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

The final part of the introduction is often dedicated to a brief overview of the rest of the paper.

In a paper structured using the standard scientific “introduction, methods, results, discussion” format, this isn’t always necessary. But if your paper is structured in a less predictable way, it’s important to describe the shape of it for the reader.

If included, the overview should be concise, direct, and written in the present tense.

- This paper will first discuss several examples of survey-based research into adolescent social media use, then will go on to …

- This paper first discusses several examples of survey-based research into adolescent social media use, then goes on to …

Full examples of research paper introductions are shown in the tabs below: one for an argumentative paper, the other for an empirical paper.

- Argumentative paper

- Empirical paper

Are cows responsible for climate change? A recent study (RIVM, 2019) shows that cattle farmers account for two thirds of agricultural nitrogen emissions in the Netherlands. These emissions result from nitrogen in manure, which can degrade into ammonia and enter the atmosphere. The study’s calculations show that agriculture is the main source of nitrogen pollution, accounting for 46% of the country’s total emissions. By comparison, road traffic and households are responsible for 6.1% each, the industrial sector for 1%. While efforts are being made to mitigate these emissions, policymakers are reluctant to reckon with the scale of the problem. The approach presented here is a radical one, but commensurate with the issue. This paper argues that the Dutch government must stimulate and subsidize livestock farmers, especially cattle farmers, to transition to sustainable vegetable farming. It first establishes the inadequacy of current mitigation measures, then discusses the various advantages of the results proposed, and finally addresses potential objections to the plan on economic grounds.

The rise of social media has been accompanied by a sharp increase in the prevalence of body image issues among women and girls. This correlation has received significant academic attention: Various empirical studies have been conducted into Facebook usage among adolescent girls (Tiggermann & Slater, 2013; Meier & Gray, 2014). These studies have consistently found that the visual and interactive aspects of the platform have the greatest influence on body image issues. Despite this, highly visual social media (HVSM) such as Instagram have yet to be robustly researched. This paper sets out to address this research gap. We investigated the effects of daily Instagram use on the prevalence of body image issues among adolescent girls. It was hypothesized that daily Instagram use would be associated with an increase in body image concerns and a decrease in self-esteem ratings.

The introduction of a research paper includes several key elements:

- A hook to catch the reader’s interest

- Relevant background on the topic

- Details of your research problem

and your problem statement

- A thesis statement or research question

- Sometimes an overview of the paper

Don’t feel that you have to write the introduction first. The introduction is often one of the last parts of the research paper you’ll write, along with the conclusion.