This site is intended for health professionals only

Read the latest issue online A manifesto for general practice nursing in 2024

Midwives play an essential role in promoting public health

See how our symptom tool can help you make better sense of patient presentations Click here to search a symptom

Receive the latest news, clinical updates and case studies straight to your inbox.

SIGN UP TODAY

Related articles

Midwives targeting key public health areas reduces health inequalities, which in turn reduces future morbidity and mortality rates in children

Most Popular

1 Managing the menopause and work: support for nurses

2 Flu vaccination programme moved to October to ‘maximise’ protection

3 Children with ‘lazy eye’ at increased risk of serious disease in adulthood

4 Long-term type 2 diabetes remission through weight loss ‘unsustainable’ for most

Sign up for news alerts Subscribe to Nursing in Practice newsletters to ensure you receive the news as it happens in your inbox.

Join the discussion and be a part of Nursing in Practice

Sharpen your skills and further your career with Nursing in Practice

- Nursing in Practice 365

- Nursing in Practice Reference

Other links

- Contact Us

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Yellow Card reporting

Get the Nursing in Practice free app

Get our free diagnosis symptom tool

Other Cogora brands

- Pulse Today

- Hospital Healthcare Europe

- The Pharmacist

- Management In Practice

- Healthcare Leader

- Hospital Pharmacy Europe

© Cogora 2024 Cogora Limited. 1 Giltspur Street, London EC1A 9DD Registered in the United Kingdom. Reg. No. 2147432

Nursing in Practice newsletters

Sign up today to receive the latest news, business insight, blogs and case studies via newsletters as it happens.

Just added to your cart

Public Health in Midwifery: Reflection Essay Guide

Identify and discuss the importance of learning outcomes from the module in relation to public health. Highlight its significance in midwifery practice.

Introduction: 250words approx • Identify and discuss the importance of relevant learning outcomes from the module in relation to the public health/health promotion that you wish to address and why this is significant in midwifery practice. • Explore and evaluate the value of reflection in developing your midwifery knowledge and practice • Highlight what you intend to discuss in the assignment and why (you can come back to this at the end but if you plan your work, you should identify this at the beginning). Ensure that your chosen reflective model is identified and justified (Discuss rationale with supporting evidence especially why one model was chosen over another). • All sections should include relevant references from credible academic sources (please review the reading list and library database).

Hire A Writer - Plagiarism-Free Essay Writing Service Body - 3500 words approx. (this will be for the whole reflective cycle you have chosen) Regardless of the chosen reflective framework, please ensure you discuss the following within the chosen framework: • Briefly summarise the topic for the poster and the group dynamics (which will enable you to discuss your own professional development later in the assignment for example – the impact of team work on content, development of poster, workload, communication, challenges. • Identify your feelings at the time and why you felt that way for example – inadequacy as you missed some session or enjoyment of the task and why(therefore, in your analysis you can pick this up to explore the necessity for preparedness). • What you learned from the experience – Evaluate the experience for example – thinking back on your ability to share information with your peers with regards to the public health/health promotion chosen topic. what worked well but what could have been improved – • You should evaluate the influence of psychological, social, cultural, political and economic factors on the woman and her family. • This section should include relevant references and reference to theory. • Analysis - you should already have identified areas for further discussion from what you have reflected on so far. • Relate your points to public health/health promotion theory (not to the poster and group work). • Communicating effectively with women and families and why this is important as part of public health/health promotion strategy • Demonstrate an understanding of the importance of good multi-agency working as part of public health/health promotion strategy • Demonstrate an understanding of the impact of your chosen health promotion model that underpins your chosen topic in relation to public health/health promotion. • This should be supported with current, academic, relevant literature. This section should conclude with a discussion on how this activity has impacted on your learning for future practice and what you will do going forward (Be specific – this relates to a conclusion and action plan).

Hire A Writer - Plagiarism-Free Essay Writing Service Conclusion: 250 words approx. Please ensure you bring all the points of your reflective account together- relating it to the module learning outcomes and your development as a result. You can include key references already cited from the body in your conclusion but keep this to a minimum. No new material should be introduced in your conclusion. Include a reference list starting on a new page.

Understanding the Importance of Reflection Reflection isn't just about looking back; it's about learning, growing, and evolving. In the realm of midwifery, it enables professionals to identify crucial learning outcomes from modules related to public health. By exploring and evaluating the value of reflection, midwives can enhance both their knowledge and practice, aligning more closely with best practices in public health. The Pillars of Reflective Practice Identifying Feelings and Emotions: Reflecting on one's feelings during specific scenarios—be it the joy of successful teamwork or the stress of missed sessions—provides a starting point. It allows midwives... Read more

Read Sample Paper Introduction Public health promotion is critical in midwifery practice (Soucy et al., 2023). It ensures that mothers and newborns receive best clinical outcomes (Smith et al., 2017). As such, midwives must understand the principles and practices of public health promotion. This knowledge enables midwives to work with mothers, families, and communities to improve their health and well-being (De Leo et al., 2019; McLellan et al., 2019). This reflection focuses on my experience of developing a health promotion poster for Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) using the Gibbs reflective model. It will explore the importance of effective communication and collaboration. It also outlines the significance of using health promotion models in promoting midwifery practice. Additionally, it evaluates the influence of psychological, social, cultural, political, and economic factors on women and their families. Reflection is an essential component of professional development in midwifery practice (Koshy et al., 2017). It enables midwives to examine their practice, identify areas for improvement, and take action to enhance their skills and knowledge (Sweet et al., 2019). Reflective practice also provides midwives with an opportunity to learn from their experiences (Sweet et al., 2019). It integrates new knowledge and skills into their practice and improves the quality of care they provide (Sweet et al., 2019). I have selected Gibbs’ reflective model for this evaluation. It consists of six stages, which are description, feelings, evaluation, analysis, conclusion, and action plan (Gibbs, 1988). This model provides a... Read More

- Share Share on Facebook

- Tweet Tweet on Twitter

- Pin it Pin on Pinterest

Leave a comment

Please note, comments must be approved before they are published

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.

- Press the space key then arrow keys to make a selection.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 08 November 2012

Public health interventions in midwifery: a systematic review of systematic reviews

- Jenny McNeill 1 ,

- Fiona Lynn 1 &

- Fiona Alderdice 1

BMC Public Health volume 12 , Article number: 955 ( 2012 ) Cite this article

26k Accesses

20 Citations

10 Altmetric

Metrics details

Maternity care providers, particularly midwives, have a window of opportunity to influence pregnant women about positive health choices. This aim of this paper is to identify evidence of effective public health interventions from good quality systematic reviews that could be conducted by midwives.

Relevant databases including MEDLINE, Pubmed, EBSCO, CRD, MIDIRS, Web of Science, The Cochrane Library and Econlit were searched to identify systematic reviews in October 2010. Quality assessment of all reviews was conducted.

Thirty-six good quality systematic reviews were identified which reported on effective interventions. The reviews were conducted on a diverse range of interventions across the reproductive continuum and were categorised under: screening; supplementation; support; education; mental health; birthing environment; clinical care in labour and breast feeding. The scope and strength of the review findings are discussed in relation to current practice. A logic model was developed to provide an overarching framework of midwifery public health roles to inform research policy and practice.

Conclusions

This review provides a broad scope of high quality systematic review evidence and definitively highlights the challenge of knowledge transfer from research into practice. The review also identified gaps in knowledge around the impact of core midwifery practice on public health outcomes and the value of this contribution. This review provides evidence for researchers and funders as to the gaps in current knowledge and should be used to inform the strategic direction of the role of midwifery in public health in policy and practice.

Peer Review reports

The reproductive period offers maternity care providers the opportunity to maximise the health and well-being of women and their families potentially impacting on public health outcomes, both short and long term. Although all maternity care providers who engage with pregnant women are presented with such opportunities, it is the midwife that could have the most significant impact from regular contact and building of relationships through continuity of care. There are interventions that could be implemented by midwives, which potentially would have a public health impact but it is important such interventions are evidence based. Recognition of the importance of the relationship between public health and midwifery was highlighted when a general review of midwifery in the UK [ 1 ], named public health as one of five key areas of interest. While the review specifically focused on midwifery in the UK, the importance of preventative public health interventions during pregnancy and the postnatal period has been emphasized on a wider scale. Millennium Development Goal 5 focuses on improving maternal health specifying a secondary target aim to achieve universal access to reproductive health by 2015 [ 2 ]. Antenatal care and adolescent pregnancy are specifically mentioned as key to achieving this target, both of which are acknowledged widely, as areas of interest to public health [ 3 , 4 ]. Other areas of national and international interest, which impact on population health (both women and families), include rising caesarean section rates and other interventions during childbirth [ 5 – 7 ], the importance of positive parenting in the early postnatal period [ 8 ] and perinatal mental health [ 9 ]. Within these areas there is opportunity for evidence based public health interventions to be implemented with a view to potentially improving the long term health of women and families.

Aim of the review

This paper presents an update of a systematic review of systematic reviews conducted in 2009. The aim of the 2009 review was to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions relevant to the public health role of the midwife. The 2009 review was commissioned and conducted within the context of the Midwifery 2020 initiative. The final report of the Midwifery 2020 initiative (Delivering Expectations) and full report of the systematic review of reviews [ 10 ] are available freely online from: http://www.midwifery2020.org . A systematic review of systematic reviews was selected as the methodology, given the breadth of this topic area and the timescale of the project. This paper outlines the review methodology and builds on the original review findings by providing new and updated information about effective high quality public health interventions which could be implemented by midwives or other health care providers for women during pregnancy and the postnatal period who have a similar role, for example, public health nurses, obstetric nurses, labour and delivery nurses or health visitors.

The Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic reviews Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines was adhered to when conducting this review [ 11 ]. A systematic search strategy was formulated and definitive search terms used relative to key public health topics within midwifery following consultation with Expert Advisory Group members and Midwifery 2020 Public Health Work Stream members. Seven key areas were identified as relevant to the public health role of the midwife, which included: screening; vulnerable groups; breast feeding; mental health and wellbeing; education and support; childbirth and lifestyle factors. The complete list of search terms is available from McNeill et al. [ 10 ].

Search strategy

Databases searched included: MEDLINE, PubMed, EBSCO (CINAHL/British Nursing Index), MIDIRS Online Database, Web of Science, The Cochrane Library, CRD (NHS EED/DARE/HTA) and EconLit. Eligibility criterion included reviews published from 1999 onwards; English language publications and reviews originating from economically developed countries as indicated by membership of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). An additional search was conducted of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, UK (NICE) website to identify key publications or findings from systematic reviews within guidelines. Reference lists of identified reviews were manually searched for additional relevant reviews. The searches were initially conducted in November 2009 and updated in October 2010. The titles and abstracts were obtained and the decision process for eligibility was conducted by all members of the project team in collaboration (JM, FL & FA). Full text was obtained of all eligible reviews and those whose eligibility could not be discerned from reading the abstract. Eligible systematic reviews also had to publish a clearly identified search strategy or detail the reference databases used.

Data extraction

Data were extracted on: number of papers included in the review; methodological details; midwifery intervention; outcome measures and results. Data were systematically extracted using a data extraction form by individual project team members and verified by one other project team member. The project team subsequently met to discuss and achieve consensus regarding any contentious issues. A parallel process of developing a logic model to act as an overarching framework to inform forward planning was also conducted. Logic models are essentially a conceptual framework, which can be used for evidence‐based decision making and planning [ 12 ]. The model is composed of midwifery inputs and activities, producing a logical pathways to short, medium and long term public health outputs.

Quality assessment and effectiveness of reviews

It is important to consider both the type of evidence included in reviews i.e. was the review restricted to randomised trials only or were other types of studies included and also assess how well the review was conducted methodologically. As such, a two stage process was employed: initially the level of evidence was graded and secondly, the methodological quality was assessed. Recognised frameworks were used to support this process [ 13 , 14 ]. In the hierarchy of evidence, randomised controlled trials are perceived as the gold standard and as the aim of this paper is to present high quality evidence, an evidence grade was given to each review based on the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network [ 13 ] framework in order to distinguish between different levels of evidence. This framework grades the associated risk of bias based on the level of evidence in a hierarchal manner from a grade of 1++ (meta analysis and RCT evidence) through to 4 (expert opinion), as outlined in Table 1 . The SIGN framework was modified as this review was restricted to systematic reviews and therefore reviews could only be graded as 1++, 1+, 1- or 2++. This paper only presents evidence which was graded 1- or above; any review graded below 1- was not deemed eligible for inclusion. Following selection of the type of evidence, the second stage focused on the methodology of eligible reviews. Clarke [ 15 ] suggests the successful interpretation of results from systematic reviews should consider the methodological conduct of the review. The methodological quality of included reviews was assessed and rated as low, medium or high quality. Appraisal of methodological quality was based on Smith et al. [ 14 ], which contains similar elements to other tools used to assess review quality, for example, the AMSTAR tool [ 16 ]. Reviews were graded as high quality if they included evidence of a search strategy, selection and inclusion criterion, assessment of publication bias and assessment of heterogeneity. Reviews were rated as medium quality if no evidence of assessment of heterogeneity or publication bias was provided and low quality reviews were those which provided evidence of a search strategy only. Effectiveness of interventions was evaluated using a similar approach to van Sluijs et al. [ 17 ]. A differentiation was made between reviews which reported a statistically significant difference (P<0.05), therefore referred to as effective and those which reported no difference in effect between control and intervention group and are referred to as inconclusive or not effective (as appropriate). This paper focuses specifically on interventions which are evidenced by a statistically significant meta analysis or where the intervention is supported by a generally positive trend of results when a meta analysis was not possible. Reviews have been included where a small number of studies reported statistically significant positive effect of the intervention however the wider interpretation of these results is limited. As outlined previously, the aim of the original review was to identify any public health intervention relevant to midwifery. However for the purpose of this paper the focus was to report on public health interventions relating to midwifery that demonstrated a statistically significant effect in favour of the intervention (referred to subsequently as effective interventions for the sake of brevity). Reviews graded 1- or above and of high methodological quality which reported evidence of no effect, are not discussed in this paper. However, they have been summarised in Table 2 [ 18 – 23 ]. In the case of any disagreement regarding grading of evidence, quality appraisal of reviews or effectiveness of the intervention, consensus was reached by discussion between all three authors.

Data synthesis

A narrative review is provided for each of the systematic reviews and in table format the number and date range of papers included, intervention(s), primary outcome or other public health outcomes of interest, results (including key statistical findings e.g. p values or odds ratios) are described and whether the review included a meta analysis or not. It was not expected that a quantitative analyses would be conducted given the diversity of interventions across the broad subject of public health.

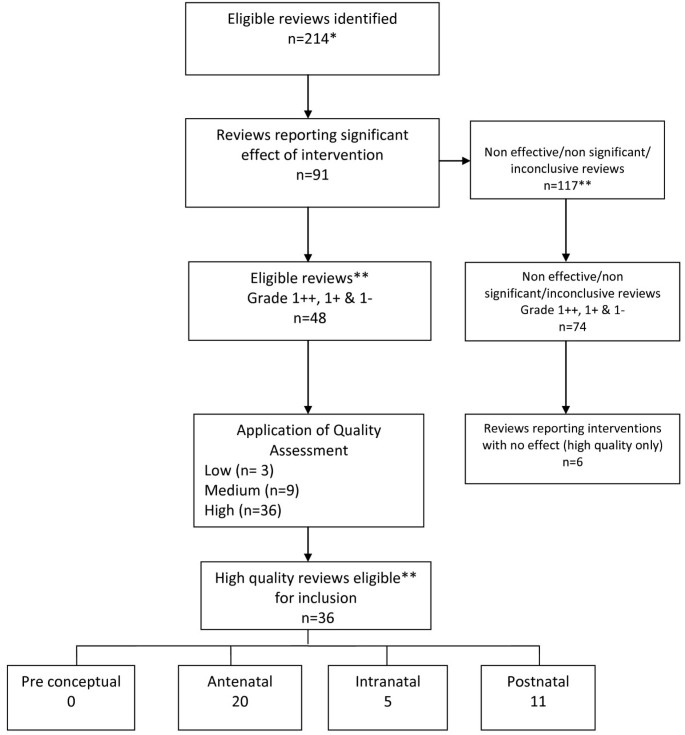

In total 214 systematic reviews were eligible of which 91 reported on effective interventions and 117 found no effect or were inconclusive. This paper only reports on high quality reviews with a level of evidence grading above 1-. Of the 91 systematic reviews which reported on effective interventions, 36 were identified which were graded as evidence level 1- or above and rated as high quality. The flow chart in Figure 1 presents the sequential process of identifying reviews eligible for inclusion in this paper. An overview of the key findings in relation to interventions demonstrating a statistically significant effect in favour of the intervention from good quality reviews will be presented in the following sections. A summary of included reviews is provided in Table 3 . The findings in this paper are presented chronologically through the reproductive period: preconceptual; antenatal; intranatal and postnatal. Within each section the reviews on similar broad topics have been further categorised: antenatal (screening; supplementation; support; education; mental health); intranatal (clinical care; environment); postnatal (breast feeding; mental health; education; support). The findings section also presents the logic model which was developed in parallel with the searching and analysis of reviews. Logic models enable the visualisation of how interventions or programmes work and the expected outcomes [ 24 ] and have been used to consider the strategic public health benefit of midwifery practice both in the short and long term [ 25 ].

Identification of effective reviews of high quality *some reviews which were included at the request of funder have been excluded from this paper eg economic reviews (n=6) **non significant, non effective or inconclusive reviews, reviews graded 2++,2+ or 2- and medium or low quality reviews are not discussed in this paper.

Findings -effective interventions

Pre conceptual.

There were no high quality reviews that reported on effective interventions in the pre conceptual period.

The majority of reviews reporting effective interventions were relevant to the antenatal period (n=20). Included reviews have been grouped into screening, supplementation, support, education and mental health.

Reviews (n=4) related to screening reported on interventions relating to ultrasound [ 26 , 27 ], lower genital tract infection screening [ 28 ] and the use of decision making aids [ 29 ]. Bricker et al. [ 26 ] conducted a large Health Technology Assessment review on the clinical and cost effectiveness and women’s views of USS. The review comprised of three systematic reviews on routine ultrasound in early pregnancy, routine ultrasound in late pregnancy and routine Doppler ultrasound in pregnancy which were published in the Cochrane database around the time of Bricker et al. [ 26 ] however, all have since been updated or revised in the Cochrane database, one of which has been included in this paper. The final conclusions of Bricker et al. [ 26 ] indicated that a two stage regimen of USS in pregnancy, one in early pregnancy (booking USS) and a second anomaly USS around 20 weeks, was recommended. Whitworth et al. [ 27 ] reviewed the use of ultrasound for fetal assessment in early pregnancy and concluded that it reduces failure to detect multiple pregnancy (RR 0.07 95% CI 0.03-0.17) and accuracy of gestational dating may reduce the number of inductions of labour for post term gestation (RR 0.59; 95% CI 0.42-0.83). The authors also reported there was no reduction in adverse outcomes or health service use by mothers or infants and long term follow up did not indicate detrimental effect on children’s physical or mental development. The impact of antenatal screening for lower genital tract infection for preventing preterm delivery was reviewed by Sangkomkamhang et al . [ 28 ]. The review included one large RCT (n=4155), which indicated that preterm birth before 37 weeks was significantly lower in a group of women randomised to a screening programme before 20 weeks’ gestation (RR 0.55; 95% CI 0.41-0.75). The review provides evidence to suggest there may be some benefit to introducing a universal screening programme for lower genital tract infection; however the results are based on the findings of one study. O’Connor et al. [ 29 ] conducted a review on the use of decision aids for people facing screening decisions. The meta analysis indicated that the use of decision aids, such as leaflets or DVD’s are better than usual care and resulted in: greater knowledge (MD 15.2 out of 100; 95%CI 11.7 to 18.7), perception of risk (RR 0.6; 95% CI 0.5 to 0.8), lower decisional conflict related to feeling uninformed (MD −8.3 of 100; 95% CI −11.9 to −4.8), lower decisional conflict related to personal values (MD −6.4; 95% CI −10.0 to −2.7), reduced the proportion of people who were passive in decision making (RR 0.6; 95% CI 0.5-0.8) and reduced the proportion of people who remained undecided post intervention (RR 0.5; 95% CI 0.3-0.8). Although the results suggest decision aids are effective, the effect size was not consistent across studies and only three of the included studies related directly to antenatal screening.

Supplementation

Eight reviews [ 30 – 37 ] considered supplementation during pregnancy including iron, micronutrients, folic acid, calcium and Long Chain-Poly Unsaturated Fatty Acids (LC-PUFA’s). Two reviews [ 30 , 31 ] focused on folic acid supplementation, both of which concurred that the risk of neural tube defect was significantly reduced with supplementation: Blencowe et al., [ 30 ]; 70% reduction; 95% CI 35-86 and Lumley et al., [ 31 ]; RR 0.28; 95% CI 0.13-0.58. Iron supplementation during pregnancy was reviewed by Pena-Rosas and Viteri [ 32 ] who included 49 trials relating to the prevention of iron deficiency or anaemia at term. The authors concluded that daily iron supplementation was associated with increased haemoglobin before birth (MD 6.00; 95% CI 2.75-9.25) and reduced risk of anaemia at term (RR 0.46; 95% CI 0.29- 0.72) based on meta analyses of high quality trials only. Shah et al. [ 33 ] reviewed multi-micronutrient supplementation on pregnancy outcomes and reported there was a reduction in the risk of low birth weight amongst women given micronutrient supplementation (12 studies, RR 0.81; 95% CI 0.73-0.91) and iron-folic acid supplementation (RR 0.83; 95% CI 0.74-0.93) compared to placebo. The mean birth weight was higher (11 studies; WMD 54g; 95% CI 36-72g) in infants born to mothers who had micronutrient supplementation compared to iron-folic acid supplementation (no difference with placebo).

Calcium supplementation was the focus of three reviews [ 34 – 36 ]. Hofmeyr et al. [ 34 ] reported a reduction in pre-eclampsia (RR 0.68; 95% CI 0.57-0.81) and fewer babies born <2500g (RR 0.83; 95% CI 0.71-0.98). However the benefits seen were from small trials and not observed in the largest trial included. Hofmeyr et al. [ 35 ] reported that with supplementation a reduction in blood pressure (RR 0.7; 95% CI 0.57-0.86), pre-eclampsia (RR 0.48; 95% CI 0.33-0.69) and maternal death/morbidity (RR 0.80; 95% CI 0.65-0.97) was noted and advocated research to investigate calcium supplementation at community level. The most recent review [ 36 ] conducted by several of the same authors as Hofymeyr et al. [ 34 ] on calcium supplementation concluded that there was a reduced risk of increased blood pressure (RR 0.65; 95% CI 0.53-0.81) and preeclampsia (RR 0.45; 95% CI 0.31-0.65). The effect was greatest for high risk women (RR 0.22; 95% CI 0.12-0.42) and women with low baseline calcium (RR 0.36; 95% CI 0.20-0.65). Maternal death or serious morbidity was reduced (RR 0.80; 95% CI 0.65-0.97) although this was mostly in low risk women and women with low calcium and there was no effect on preterm births, stillbirth or death before discharge. Horvath et al. [ 37 ] reviewed the effect of advising high-risk pregnant women to take LC-PUFA supplementation on a number of pregnancy outcomes. The authors found a significantly lower rate of PTD <34 wks (RR 0.39; 95% CI 0.18-0.84) although this result was based on two trials (n=291). There was no effect on duration of pregnancy, PTD <37 wks, infant birth weight or the occurrence of IUGR. Although significant, the authors concluded that there was not enough evidence to recommend routine use of LC-PUFA supplements by high-risk women and that further research involving larger sample sizes was needed.

Three reviews [ 38 – 40 ] considered different types of supportive interventions for women during pregnancy. These ranged from using midwifery models of care to provision of emotional support to reduce the risk of preterm delivery or low birth weight infants. Hatem et al. [ 38 ] reviewed midwife led models of care versus other models of care and concluded that the majority of women should be offered midwifery led care. Women who had midwife led models of care were less likely to experience antenatal hospitalisation (RR 0.90; 95% CI 0.81-0.99), use of regional analgesia (RR 0.81; 95% CI 0.73-0.91), episiotomy (RR 0.82; 95% CI 0.77-0.88) and instrumental delivery (RR 0.86; 95% CI 0.78 to 0.96) and were more likely to experience no intrapartum analgesia/anaesthesia (RR 1.16; 95% CI 1.05-1.29), vaginal delivery (RR 1.04; 95% CI 1.02-1.06), to feel in control during childbirth (RR 1.74; 95% CI 1.32-2.30), attendance at birth by a known midwife (RR 7.84; 95% CI 4.15-14.81) and initiate breastfeeding (RR 1.35; 95% CI 1.03 to 1.76). In addition, women who were randomised to receive midwife-led care were less likely to experience fetal loss before 24 weeks’ gestation (RR 0.79; 95% CI 0.65-0.97). There was no difference between groups for birth by caesarean section (RR 0.96; 95% CI 0.87-1.06) and no statistically significant differences in fetal loss/neonatal death of at least 24 weeks (RR 1.01; 95% CI 0.67-1.53) or fetal/neonatal death overall (RR 0.83; 95% CI 0.70-1.00) and their babies were more likely to have a shorter length of hospital stay (mean difference in days: -2.00; 95% CI −2.15 to −1.85). Hodnett & Fredericks [ 39 ] assessed the value of emotional support to women who were judged, by a health professional, to be at increased risk of preterm delivery or having a low birth weight baby. No significant effect was detected for either outcome, however, women receiving support interventions were significantly less likely to undergo a caesarean section (RR 0.88; 95% CI 0.79-0.98) and were more likely to terminate their pregnancy (RR 2.96; 95% CI 1.42-6.17). There was also a trend towards improvement in maternal psychosocial outcomes although this was not significant. Denis & Kingston [ 40 ] reviewed the effect of telephone support during pregnancy and early postpartum period specifically on smoking, preterm birth, low birth weight, breast feeding and postpartum depression. The authors report a positive effect on breast feeding (3 trials; n=618; RR=1.18; 95% CI 1.05-1.33), low birth weight (3 trials; n=2,027; RR=0.78; 95% CI 0.63-0.97) and postpartum depression at 4 weeks (RR 0.24; 95% CI 0.06-1.00) and 8 weeks (RR 0.30; 95% CI 0.10-0.92), although all were from small numbers of trials and the finding on postpartum depression was from one pilot trial including 42 women.

Educational interventions in the antenatal period were the focus of four systematic reviews [ 41 – 44 ] that considered education about pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) and promotion of smoking cessation in pregnancy Lumley et al. [ 41 ] reviewed the effect of interventions for promoting smoking cessation and included 72 studies of which 56 were RCT’s. Interventions to encourage cessation of smoking had a significant effect on the number of women smoking; 6 out of every 100 stopped, and a reduction in the number of cigarettes smoked by women was also evident. There was a significant reduction of smoking in late pregnancy (RR 0.94; 95% CI 0.93-0.96), reduction in LBW (RR 0.83; 95% CI 0.73 -0.95), preterm birth (RR 0.86; 95% CI 0.74-0.98) and an increase in mean birth weight (53.91g; 95% CI 10.44g - 95.38g). Naughton et al. , [ 42 ] reviewed the use of self help interventions for smoking and reported greater likelihood of quitting compared to usual care (13.2% v 4.9%; OR 1.83; 95% CI 1.23-2.73). The cost effectiveness of this method was also emphasised, however, further research is necessary to determine the intensity level of the intervention to maximise effectiveness. Hay-Smith et al. [ 43 ] and Lemos et al. [ 44 ] reviewed pelvic floor muscle training and concluded that for primigravida women PFMT was effective. Hay-Smith et al. [ 43 ] reported that women without prior incontinence were less likely to report incontinence in late pregnancy (RR 0.44; 95% CI 0.30-0.65) and up to 6 months postpartum (RR 0.71; 95% CI 0.52-0.97) similar to Lemos et al. [ 44 ] who reported significantly reduced development of urinary incontinence from 6 weeks to 3 months after delivery (OR 0.45; 95% CI 0.3-0.66; 4x RCT; n=675). Pregnant women with persistent incontinence 3 months after delivery and received PMFT were less likely to report urinary incontinence at 12 months post delivery (RR 0.79; 95% CI 0.70-0.90) and less likely to report faecal incontinence at 12 months (RR 0.52; 95%CI 0.31-0.87) [ 43 ].

Mental health

One review by Dennis & Creedy [ 45 ] considered interventions to prevent postnatal depression and all but one involved an intervention from a health professional. The authors reported that preliminary evidence suggests that intensive postnatal nursing home visits with at risk mothers assisted prevention of postpartum depression (RR 0.67; 95%CI 0.51-0.89).

Eligible systematic reviews relevant to the intranatal period yielded the smallest number in comparison to either the antenatal or postnatal periods. Five reviews [ 46 – 50 ] were included in this section and considered either clinical care during labour/delivery or the birthing environment.

Clinical care

Cluett & Burns [ 46 ] reviewed immersion in water for labour or birth (n=11) and reported from a meta analysis of 6 RCT’s. There was evidence to indicate that immersion in water for the first stage of labour significantly reduced the rate of epidural, spinal, paracervical analgesia and anaesthetic analgesia (478/1254 versus 529/1245; OR 0.82; 95% CI 0.70-0.98; p 0.025). However further research is required on other outcomes where there was no difference identified including assisted vaginal deliveries, C/S, perineal trauma, maternal infection, Apgar score < 7 at 5 mins, neonatal unit admissions or neonatal infection rates. Rabe et al. [ 47 ] reviewed delayed umbilical cord clamping and indicated from a meta analysis that there are benefits for both term and preterm infants. A delay of 30–120 seconds of cord clamping reduced the need for transfusions (RR 2.01; 95% CI 1.24-3.27, p=0.0049) and intraventricular haemorrhage (RR 1.74; 95% CI 1.08-2.81, p=0.022) in infants born <37 weeks [ 47 ]. Although the short term benefits are clear, further longitudinal work is needed to clarify the long term benefits.

Environment

The birth setting was the subject of four reviews although all were on different aspects. Hodnett et al. [ 48 ] reviewed the evidence regarding alternative versus conventional institutional settings for birth, which did not include any trials conducted in free standing birth centres. The review reported that for women allocated to the intervention (alternative setting) there was a significant increased likelihood of no analgesia/anaesthesia (RR 1.17; 95% CI 1.01-1.35), spontaneous vaginal delivery (RR 1.04; 95% CI 1.02-1.06), very positive views of care (RR 1.96; 95% CI 1.78-2.15), breastfeeding rates at 6–8 weeks (RR 1.04; 95% CI 1.02-1.06) and decreased episiotomy rate (RR 0.83; 95% CI 0.77-0.90). There was no effect on serious perinatal or maternal morbidity or mortality. Continuous support during childbirth was reviewed by Hodnett et al. [ 49 ]. The intervention involved one to one support during labour and found increased likelihood of shorter labour (WMD −0.43 hours; 95% CI −0.83 to −0.04), spontaneous vaginal delivery (RR 1.07; 95% CI 1.04 to 1.12) and were less likely to have intrapartum analgesia (RR 0.89; 95% CI 0.82- 0.96) or report dissatisfaction with childbirth experience (RR 0.73; 95% CI 0.65- 0.83). The authors only reported on outcomes where at least four trials were included in the meta analysis and highlighted that, generally, continuous intrapartum support was associated with greater benefits when it was not a member of hospital staff, when it began in early labour and in settings where epidural was not routinely available. Hodnett et al. [ 49 ] concluded that continuous support should be the norm rather than the exception for all women and further research is required as to the effectiveness of doula or lay support.

One review considered interventions aimed at reducing caesarean section rates [ 50 ]. Chaillet & Dumont [ 50 ] reported from a meta analysis that regular audit, detailed feedback regarding aspects of caesarean section performance (responsibility for decision making, rates, review of cases in clinical practice and multi faceted strategy approaches, such as development of guidelines, education of health professionals and women about vaginal birth after caesarean section (VBAC) were effective for reducing the caesarean section rate (RR 0.81; 95% CI 0.75-0.87). Details of relative risk for each type of strategy are included in Table 3 .

Eleven reviews [ 51 – 61 ] reporting on effective interventions related to the postnatal period. The reviews ranged across four areas: breast feeding; mental health; education and support.

Breast feeding

Reviews on this topic generally related to either support or promotion of breastfeeding. Britton et al. [ 51 ] reviewed the evidence in relation to support for breastfeeding mothers and key findings indicated that all forms of extra support for any breastfeeding (exclusive or partial) increased the duration of breastfeeding (RR 0.91; 95% CI 0.86-0.96) and the effect was greater for exclusive breastfeeding (RR 0.81; 95% CI 0.74-0.89). These findings were supported by Chung et al. [ 52 ] and Sikorski et al. [ 53 ]. Breastfeeding interventions included in both Britton et al. [ 51 ] and Chung et al. [ 52 ] involved formal or structured breastfeeding education, informal breastfeeding education or breastfeeding support either lay or professional. Chung et al. [ 52 ] from a meta analysis of 34 studies reported that breastfeeding interventions were effective in relation to increasing short term (1-3mths) and long-term (6-8mths) exclusive breastfeeding (RR 1.28; 95% CI 1.11-1.48 and RR 1.44; 95% CI 1.13-1.84) although statistically significant heterogeneity was noted for short term exclusive breast feeding (I 2 =55%; p= 0.006). The authors also highlighted an increased rate (22%) of any (RR 1.22; 95%CI 1.08-1.37) and exclusive (RR 1.65; 95%CI 1.03-2.63) short term breastfeeding with interventions that included a component of lay support. Sikorski et al. [ 53 ] reviewed additional support versus standard care and concluded that additional professional support was more beneficial than standard care for duration of any breastfeeding (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.81-0.97; 10xRCT; n=19,696) and additional lay support was effective in reducing the cessation of exclusive breastfeeding (RR 0.66; 95% CI 0.49-0.89; 5xRCT; n=2530). Effect sizes for interventions with an antenatal education element (RR 0.85; 95% CI 0.70-1.04) were not statistically significant, while those with a postnatal element alone were (RR 0.80; 95% CI 0.80-0.96). Four trials using WHO/UNICEF training showed significant benefit in prolonging exclusive breastfeeding (RR 0.70; 95% CI 0.53-0.93), but were highly heterogeneous. The authors highlight the need to assess support in different settings especially with low rates, conduct economic analyses and use qualitative research to explore specific elements of support. Dyson et al. [ 54 ] focused on breastfeeding initiation rates and indicated from a meta analysis of five studies (n=582) that breastfeeding education had a significant effect on increasing initiation rates (RR 1.57, 95% CI 1.15-2.15, p=0.005) compared to standard care in low income groups although substantial statistical heterogeneity was noted (I 2 =53.4%). Early skin to skin contact was reviewed by Moore et al. [ 55 ] who reported statistically significant effects of early skin to skin on breastfeeding at one to four months post birth (OR 1.82, 95% CI 1.08-3.07) and breastfeeding duration (WMD 42.55, 95% CI −1.69 -86.79). In this review, data from more than two trials were only available for a small number of outcomes (8/64). Ahmed & Sands [ 56 ] reviewed breast feeding interventions. While the authors were unable to conduct a meta analysis they found from individual trials, statistically significant results relating to kangaroo care, peer counselling, in home breast milk measurement, and post discharge lactation support for improving breast feeding outcomes.

One review focused on improving maternal mental health and considered postnatal psychological and psychosocial interventions [ 57 ]. Dennis & Hodnett [ 57 ] reported that any psychosocial or psychological intervention compared to usual postpartum care was associated with a reduction in the likelihood of continued depression from their review of nine trials. Examples of psychosocial and psychological interventions reviewed included non-directive counselling, supportive interactions, delivered via telephone, home or clinic visits, or individual or group sessions in the postpartum period by a health professional or lay person, cognitive behavioural therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy.

Education and support

One review considered support for women in relation to weight reduction in the post partum period [ 58 ] focusing on the effect of diet or exercise or both for reducing weight after childbirth. They found that women who took part in a diet (1 trial; n=45; WMD −1.70 kg; 95% CI −2.08 to −1.32; z=8.73; p<0.00001), and women on a diet plus exercise programme (4 trials; n=169; WMD −2.89 kg; 95% CI −4.83 to −0.95; z=2.92; p<=0.00049), lost significantly more weight than women in the usual care. The authors also noted that there was no adverse effect on breastfeeding, although cautioned that further research is necessary to confirm this finding. Three reviews considered extra support for vulnerable groups of women in the form of home visiting or parenting interventions [ 59 – 61 ]. Corcoran & Pillai [ 59 ] reviewed rates in repeat pregnancy following the introduction of hospital-based programmes providing education and counselling to a sample of adolescent mothers. They found that although there was a 50% reduction in the odds of repeat pregnancy compared to comparison-control conditions at 19months (OR 0.474; 95% CI 0.322-0.695), the effect had dissipated by 31 months. All studies were US based and the majority conducted in low income groups (74%) and African Americans (60%). Two reviews focused on parenting interventions [ 60 , 61 ]. Pinquart and Teubert [ 60 ] reported small effects on parenting, parental stress, child abuse, health promoting behaviour, cognitive, social development, motor development, child mental health, parental mental health & couple adjustment from parenting education interventions. Vanderveen et al. [ 61 ] demonstrated an overall positive effect on neurodevelopment from early parental interventions (all involved teaching or enhancing parental skills) lasting up to 36 months. Meta analysis of twelve studies indicated higher cognitive scores at 12 months (WMD 5.57; 95% CI 2.29-8.86; p=0.0009), at 24 months (7 studies; WMD 7.59; 95% CI 5.01-14.31; p=0.0003) and at 36 months (2 studies; WMD 9.66; 95% CI 5.01-14.31; p=0.0001), but not at 5 yrs (3 studies p=0.24). The authors suggest further research is needed to clarify the most effective interventions and the long term effect.

Logic model

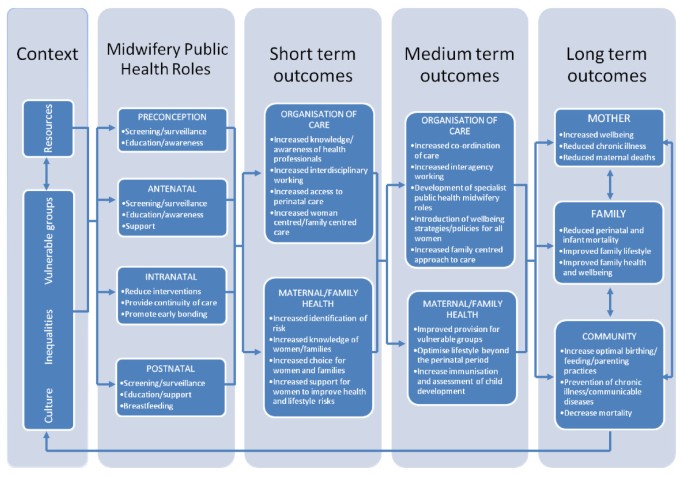

The parallel development of the logic model resulted in a summary model (Figure 2 ) provides a framework to visualise interventions across the perinatal period and the potential short, medium and long term impact on the health of women, their families and the community. Logic models display relationships between the core elements (context; inputs; outputs and outcomes) and the basic concept is to read from left to right, following a sequence of reasoning. An example of this is provision of education and information about screening in the antenatal period; an aspect of care where inequalities are known to occur [ 62 ]. The context in this example refers to the cultural, political, social circumstances in which the provision of screening is situated. Reading from left to right on the model indicates that the midwifery public health intervention is next so for example if a midwife provides information about antenatal screening for HIV (input), then uptake of screening may improve and at risk women will be identified earlier (outputs) and the effect will improve maternal and infant health during pregnancy. The medium and longer term outcomes are the resultant reduction in morbidity and or mortality in the local population.

Summary Logic Model.

The focus of this paper is the development of the public health role of the midwife based on effective interventions and highlighting the short, medium and long term effects that these interventions could bring about. Any intervention must be considered within the context in which it is to be delivered as inequalities, resources, culture and vulnerable groups can influence the choice of intervention to best suit the population of women being served. The second column represents the inputs or activities; these are the interventions which are intended to bring about the change in outcomes. In relation to public health and midwifery these are interventions that may impact on public health primarily through education, screening and support. The outputs are the products or the targets of the service delivered and can been seen in the boxes entitled organisation of care under short and medium term outcomes. While the logic model provides a visual outline of midwifery public health roles, using this approach facilitates understanding of how public health programs can be planned and subsequently evaluated. Conducting the data synthesis in tandem with developing the logic model has also highlighted where the gaps in knowledge are and identified areas where midwives could potentially have a much greater role and subsequent impact on public health.

This paper sought to report on systematic reviews providing high quality evidence of effective interventions, in essence the ‘cream of the crop’. Reviews reporting on effective interventions were those which presented a statistically significant meta analysis or where the intervention was supported by a generally positive trend of results when a meta analysis was not possible to ensure the recommendations of the paper are based on strong evidence of good quality. There were a number of reviews included which presented statistically significant positive findings. However, in some cases these were limited by small numbers of participants or small numbers of trials included in the review. As a result of conducting the review and analyzing eligible systematic review evidence, three key areas for future consideration were identified including: recommendation and implementation of effective evidence; gaps in knowledge and developing the role of the midwife in public health which are discussed further in the following sections.

Recommendation and implementation of effective evidence

It is clear from this review of effective interventions, there are areas where evidence has been incorporated into guidelines and thus recommended for implementation into routine practice. However, it has also highlighted many areas where it has not. There has been extensive debate and commentary in the literature about knowledge transfer and translation of knowledge into practice, however, this paper confirms that despite the existence of good quality evidence, the gap remains. From this review, several effective interventions were identified, which are already recommended as routine practice, for example education about folic acid supplementation and pelvic floor muscle training to prevent or reduce the risk of urinary incontinence are advocated by current practice guidelines in the UK [ 63 ] and further afield [ 64 , 65 ]. However, to evaluate fully the extent to which guidelines have been applied it is essential to audit practice in order to provide evidence for knowledge transfer. To encourage implementation of NICE guidelines, audit support tools have been developed by NICE on antenatal care or diabetes in pregnancy for use at local level. Effective interventions were also identified which could easily be implemented by a midwife and could potentially impact on public health, such as education programs for parents of preterm infants and implementation of specific strategies to reduce caesarean section rates. Although there is recognition by health professionals these areas are important, this review provides definitive evidence and examples from systematic reviews, of interventions that are effective. Further consideration needs to be given to how to translate these effective interventions into practice using appropriate channels which are effective to facilitate knowledge transfer. These may include stronger collaborations between clinicians and academics and increasing the exposure students have to systematic reviews in education curricula at undergraduate level. Other effective interventions have been implemented on an ad hoc basis for example additional lay or professional support for breast feeding women and strategies to reduce caesarean section rates, which need to be included specifically in policy and strategy documents to ensure widespread implementation and thus contribute to an evidence based public health agenda to improve the health of women and families. Although this paper has focused on reporting effective interventions it is also important to take cognisance of those interventions that are not effective i.e. those which do not work and sometimes are deeply embedded into practice, for example, routine antenatal CTG for fetal assessment [ 20 ]. It was not possible to discuss reviews that demonstrated no effect within this current paper, however, Table 2 provides summary details of the areas where this was the case.

Gaps in knowledge

The review identified many gaps in systematic review literature relating to core midwifery practice, which potentially could impact on public health population goals. The UK Department of Health, Public Health Strategy [ 66 ] emphasizes the importance of improving maternal health and the subsequent impact on reducing infant mortality and premature births and yet this review identified limited systematic review evidence to support the implementation of midwifery interventions that could impact on perinatal morbidity and mortality. The review also highlighted it was difficult to accurately assess the potential public health impact in terms of effectiveness as some interventions were not well evaluated, evidenced by the large number of inconclusive reviews and reviews demonstrating no effect. The review of reviews identified some interventions that were effective but were limited in terms of methodological quality of included studies, for example, small numbers and design flaws, thus demonstrating the need for robust research and evaluation. One example of this is systematic review evidence in relation to weight management or obesity; a topic of growing concern to maternity care providers and yet the evidence from systematic reviews is limited in terms of quality. The systematic reviews included in the original review generally indicated that additional support related to diet or exercise for women in the postnatal period was effective, however, only one review was of a high quality. Another example of this is the evidence around home visiting for vulnerable groups of women in the postnatal period. While a significant body of research, including longitudinal studies has been published on parenting interventions indicating generally positive effects [ 67 , 68 ] the evidence from this current systematic review of reviews is mixed. Current early years governmental policy in the UK focuses on giving children the best start in life and various interventions have been, or are currently being rolled out, for example, SureStart and the Family Nurse Partnership, however the longer term impact on women and families remains to be seen. Logic models highlight the causal linkage between inputs, outputs and outcomes (24). This is illustrated very clearly in relation to support for parents in the form of parenting interventions (input) which can result in the short term outcome of increasing support for women to improve health and lifestyle; optimize lifestyle and child development beyond the immediate perinatal period (medium term) and in the long term improve family health and wellbeing for this generation and those to come.

Developing the role of the midwife in public health

In order for midwives to utilise their potential in relation to public health it is important not only to consider the interventions that could be implemented but also take cognisance of wider strategies and policy relating to public health. The logic model (Figure 2 ), which was developed as a parallel process to the review, provides an overarching framework that should be used by midwives to visualise their contribution to public health. The model illustrates possible future roles but also facilitates recognition of the current contribution of midwives to improving the health of women and their families as part of their core role. An example of this is how vulnerable women (either social or medical) could be identified in the antenatal period by midwives and a supportive or educational intervention implemented which would result in improved outcomes in the short term i.e. reduced pre term birth or improved birth weight. A medium term outcome of this intervention would focus on optimising lifestyle beyond the perinatal period for example collaborating with health visiting services to provide education and support that would potentially have a longer term outcome of improved family health and well being. The review did not identify any systematic reviews which specifically focused on interventions relating to midwifery public health roles, highlighting a gap in review evidence. Biro [ 69 ] suggests it may be challenging for midwives to think beyond individual women but ultimately necessary in order to meet the challenge of public health to improve population health. Reframing routine midwifery activities in a public health context, identifying midwives as public practitioners and building on existing activities, such as collaboration, organisation of care and interagency working are essential to clearly define the relationship between midwifery and public health. An earlier, wider review on health-led parenting interventions in pregnancy and the first three years of life [ 8 ] suggested that many interventions, particularly in relation to supporting parenting, could be provided as part of routine care and that although the optimal time to start programmes was not clear, there was some consensus that those initiated in the antenatal period were more effective. Development of the public health role of the midwife will also require strategic thinking and support from planners and commissioners of maternity services to ensure that midwives can influence policy and effectively implement public health strategies. This will involve dedicating time and resources to develop local policies, providing training for midwives and building good relationships with other healthcare disciplines to work together.

Limitations

There are a number of methodological challenges in using systematic review evidence which must be taken into account. It is difficult to summarise the evidence from systematic reviews as often there is significant diversity between interventions included in individual reviews or outcome measures used. In addition the results presented may be inconsistent between reviews or inconclusive, however, Smith et al. [ 14 ] suggest the strength of systematic reviews of reviews is that the best quality reviews can be highlighted in a single document. Systematic reviews are generally limited to published work and thus may be subject to publication bias. In addition, more recent, potentially conflicting, research may be available since the review was published or there may be effective interventions that have not been evaluated in a systematic review. A recent Cochrane overview of systematic reviews [ 70 ] highlighted that such reviews provide an accessible summary on the totality of the evidence in the area and minimised the need for referral to individual reviews, however suggested that readers may wish to do so for specific details. This review was similar in that it covered a broad scope of the evidence in relation to public health, providing a strategic overview while also providing a valuable resource for those who wish to consult individual reviews for additional specific details. In this paper, only high quality reviews (based on level of included evidence and methodology of review) reporting on effective interventions were included. While this provides reassurance regarding review findings, in that the conclusions are based on top level evidence, some interventions demonstrating effect may have been excluded because the review itself did not meet either the quality or level of evidence criteria for inclusion. In most cases this relates to areas worthy of future investigation, which need more robust evaluations. The search strategy utilised in the review was specifically focused on the public health role of the midwife and therefore incorporated key terms relative to key areas. However in doing so, some postnatal interventions, which extend beyond the role of the midwife, for example, parenting interventions that continue into early childhood may not have been included. In addition, due to the inclusion and exclusion criteria applied, it is possible that extensive broad reviews on particular topics have been excluded from this review due to the nature of evidence included within them, for example, the NICE Guideline on Antenatal and Postnatal Mental Health [ 9 ]. However, it is recognised these are valuable resources and contribute to wider understanding on specific subjects.

This paper has reported on high quality effective interventions identified from a larger systematic review on public health interventions that could be delivered primarily by midwives or maternity care providers. From the effective interventions identified it is clear that while some have been recommended for implementation into routine practice, others have not. This highlights the continuing gap between evidence and practice and the need for professionals and researchers to work better together to ensure specific interventions that are effective, are translated into practice and subsequently audited to provide evidence of knowledge translation. The public health role of the midwives has not been well researched or reviewed and the impact of everyday midwifery practice on longer term, holistic maternal and family well-being outcomes is poorly articulated in review literature. A shift in research, policy and practice is needed to fully articulate the public health role of the midwife. This systematic review of systematic reviews identifies a number of effective interventions that provide a useful starting point on which to build future practice. The logic model demonstrates the need to fill in major gaps in our knowledge on effective interventions to achieve both short and long term public health benefits for women and their families. Such benefits will remain elusive without investment in a collaborative, strategic approach to the role of public health in midwifery.

Advisory group members

Ms Liz Bannon , Senior Midwife, & Co Director of Maternity Services, Social Services, Family & Child Care Belfast Health and Social Care Trust, Belfast, Northern Ireland; Professor Debra Bick , Professor of Evidence Based Midwifery Practice, Kings College London, England; Dr Helen Cheyne , Nursing, Midwifery & Allied Professions Research Unit, University of Stirling, Scotland; Professor Mike Clarke , then Professor of Clinical Epidemiology & Director of UK Cochrane Centre, now Professor/Director of MRC Methodology Hub, Queen’s University Belfast; Ms Joanne Gluck , Consumer Representative; Professor Billie Hunter , Professor of Midwifery, Swansea University, Wales; Dr Dermot O’Riley , Centre of Excellence for Public Health Northern Ireland, Queen’s University Belfast, Northern Ireland.

Midwifery 2020 Programme: Midwifery 2020: Delivering Expectations. 2010, London: Midwifery 2020

Google Scholar

United Nations: The millennium development goals report 2008. 2008, New York: United Nations Department of Social and Economic Affairs

Thomson G, Dykes F, Singh G, Cawley L, Dey P: A public health perspective of women's experiences of antenatal care: An exploration of insights from a community consultation. Midwifery. 2012, 10.1016/j.midw.2012.01.002. Epub ahead of print

Whitehead E: Understanding the association between teenage pregnancy and intergenerational factors: a comparative and analytical study. Midwifery. 2009, 25: 147-154. 10.1016/j.midw.2007.02.004.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Declercq E, Young R, Cabral H, Ecker J: Is a rising cesarean delivery rate inevitable? trends in industrialized countries, 1987 to 2007. Birth. 2011, 38 (2): 99-104. 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2010.00459.x.

Green J, Baston H: Have women become more willing to accept obstetric interventions and does this relate to mode of birth? data from a prospective study. Birth. 2007, 34 (1): 6-13. 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2006.00140.x.

Weaver J, Statham H, Richards M: Are there “Unnecessary” cesarean sections? perceptions of women and obstetricians about cesarean sections for nonclinical indications. Birth. 2007, 34 (1): 32-41. 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2006.00144.x.

Barlow J, Schrader McMillan A, Kirkpatrick S, Ghate D, Smith M, Barnes J: Health-led parenting interventions in pregnancy and early years. 2008, London: Department for Children, Schools and Families

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health: Antenatal and postnatal mental health: The NICE guideline on clinical management and service guidance. NICE guideline CG45. 2007, London: The British Psychological Society & The Royal College of Psychiatrists

McNeill J, Lynn F, Alderdice F: Systematic review of reviews: the public health role of the midwife. 2010, Scotland: NHS Education for Scotland. Available online from, http://www.midwifery2020.org/Public%20Health/index.asp . Accessed 15th September 2012.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009, 339: b2535-10.1136/bmj.b2535.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Chiappelli F, Cajulis OS: The logic model for evidence-based clinical decision making in dental practice. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2009, 4: 206-210.

Article Google Scholar

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network: Systematic literature review. 2008, Available at: http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/50/ section6.htm. Accessed 27 March 2012,

Smith V, Devane D, Begley CM, Clarke M, Higgins S: A systematic review and quality assessment of systematic reviews of randomised trials of interventions for preventing and treating preterm birth. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009, 142: 3-11. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2008.09.008.

Clarke M: Interpreting the results of systematic reviews. Semin Hematol. 2008, 45: 176-180. 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2008.04.002.

Shea BJ, Hamel C, Wells GA, Bouter LM, Kristjansson E, Grimshaw J, Henry DA, Boers M: AMSTAR is a reliable and valid measurement toll to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemol. 2009, 62: 1013-1020. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.10.009.

van Sluijs EMF, McMinn AM, Griffin SJ: Effectiveness of interventions to promote physical activity in children and adolescents: systematic review of controlled trials. BMJ. 2007, 335: 703-707. 10.1136/bmj.39320.843947.BE.

Bricker L, Neilson JP, Dowswell T: Routine ultrasound in late pregnancy (after 24 weeks' gestation). Cochrane database of systematic reviews issue 4, . 2008, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons

Carroli G, Piaggio G, Khan-Neelofur D: WHO systematic review of randomised controlled trials of routine antenatal care. Lancet. 2001, 357: 1565-1570. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04723-1.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Grivell RM, Wong L, Bhatia V: Regimens of fetal surveillance for impaired fetal growth. Cochrane database of systematic reviews issue 1. 2009, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons

Kongnyuy EJ, Wiysonge CS, Shey MS: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of prenatal and postnatal vitamin A supplementation of HIV-infected women. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2009, 104: 5-8. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.08.023.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Rumbold A, Duley L, Crowther CA, Haslam Ross R: Antioxidants for preventing pre-eclampsia. Cochrane database of systematic reviews issue 1. 2008, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons

Villar J, Carroli G, Khan-Neelofur D, Piaggio GGP, Gülmezoglu AM: Patterns of routine antenatal care for low-risk pregnancy. Cochrane database of systematic reviews issue 4. 2001, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons

Kellogg Foundation WK: Logic model development guide. 2004, Michigan: WK Kellogg Foundation

Midwifery 2020: Public health workstream final report. 2012, available from http://www.midwifery2020.org/documents/2020/Public_Health.pdf . accessed 15th September,

Bricker L, Garcia J, Henderson J, Mugford M, Neilson J, Roberts T, Martin MA: Ultrasound screening in pregnancy: a systematic review of the clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and women's views. Health Technol Assess. 2000, 16: 1-193. 10.1017/S0266462300016111.

Whitworth M, Bricker L, Neilson JP, Dowswell T: Ultrasound for fetal assessment in early pregnancy. Cochrane database of systematic reviews issue 4. 2010, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons

Sangkomkamhang US, Lumbiganon P, Prasertcharoensook W, Laopaiboon M: Antenatal lower genital tract infection screening and treatment programs for preventing preterm delivery. Cochrane database of systematic reviews issue 2. 2008, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons

O’Connor AM, Bennett CL, Stacey D, Barry M, Col NF, Eden KB, Entwistle VA, Fiset V, Holmes-Rovner M, Khangura S, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Rovner D: Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane database of systematic reviews issue 3. 2009, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons

Blencowe H, Cousens S, Modell B, Lawn J: Folic acid to reduce neonatal mortality from neural tube disorders. In J Epidemiol. 2010, 39: i110-i121. 10.1093/ije/dyq028.

Lumley J, Watson L, Watson M, Bower C: Periconceptional supplementation with folate and/or multivitamins for preventing neural tube defects. Cochrane database of systematic reviews issue 3. 2001, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons

Pena-Rosas JP, Viteri FE: Effects and safety of preventive oral iron or iron+folic acid supplementation for women during pregnancy. Cochrane database of systematic reviews issue 4. 2009, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons

Shah PS, Ohlsson A: Effects of prenatal multimicronutrient supplementation on pregnancy outcomes: a meta analysis. CMAJ. 2009, 180 (12): E99-E108. 10.1503/cmaj.081777.

Hofmeyr GJ, Roodt A, Atallah A, Duley L: Calcium supplementation to prevent pre-eclampsia: a systematic review. S Afr Med J. 2003, 93: 224-228.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Hofmeyr GJ, Duley L, Atallah A: Dietary calcium supplementation for prevention of pre-eclampsia and related problems: a systematic review and commentary. BJOG. 2007, 114: 933-943. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01389.x.

Hofmeyr GJ, Lawrie TA, Atallah AN, Duley L: Calcium supplementation during pregnancy for preventing hypertensive disorders and related problems. Cochrane database of systematic reviews issue 8. 2010, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons

Horvath A, Koletzko B, Szajewska H: Effect of supplementation of women in high-risk pregnancies with long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids on pregnancy outcomes and growth measures at birth: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Nutr. 2007, 98: 253-259. 10.1017/S0007114507709078.

Hatem M, Sandall J, Devane D, Soltani H, Gates S: Midwife-led versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane database of systematic reviews issue 4. 2008, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons

Hodnett ED, Fredericks S: Support during pregnancy for women at increased risk of low birth weight babies. Cochrane database of systematic reviews issue 3. 2003, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons

Dennis C-L, Kingston D: A systematic review of telephone support for women during pregnancy and the early postpartum period. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2008, 37: 301-314. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00235.x.

Lumley J, Chamberlain C, Dowswell T, Oliver S, Oakley L, Watson L: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. 2009, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons

Chapter Google Scholar

Naughton F, Prevost AT, Sutton S: Self-help smoking cessation interventions in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2008, 103: 566-579. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02140.x.

Hay-Smith J, Morkved S, Fairbrother KA, Herbison GP: Pelvic floor muscle training for prevention and treatment of urinary and faecal incontinence in antenatal and postnatal women. Cochrane database of systematic reviews issue 4. 2008, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons

Lemos A, Impieri De Souza A, Ferreira ALCG, Figueiroa JN, Cabral-Filho JE: Do perineal exercises during pregnancy prevent the development of urinary incontinence? A systematic review. Int J Urol. 2008, 15: 875-880. 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2008.02145.x.

Dennis C-L, Creedy DK: Psychosocial and psychological interventions for preventing postpartum depression. Cochrane database of systematic reviews issue 4. 2004, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons

Cluett ER, Burns E: Immersion in water in labour and birth. Cochrane database of systematic ReviewsIssue 2. 2009, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons

Rabe H, Reynolds GJ, Diaz-Rosello JL: Early versus umbilical cord clamping in preterm infants Cochrane database of systematic reviews issue 4. 2004, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons

Hodnett ED, Gates S, Hofmeyr G, Justus SC: Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane database of systematic reviews issue 3. 2007, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons

Hodnett ED, Downe S, Walsh D, Weston J: Alternative versus conventional institutional settings for birth. Cochrane database of systematic reviews issue 9. 2010, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons

Chaillet N, Dumont A: Evidence-based strategies for reducing cesarean section rates: a meta-analysis. Birth. 2007, 34: 53-64. 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2006.00146.x.

Britton C, McCormick FM, Renfrew MJ, Wade A, King SE: Support for breastfeeding mothers. Cochrane database of systematic reviews issue 1. 2007, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons

Chung M, Raman G, Trikalinos T, Lau J, Ip S: Interventions in primary care to promote breastfeeding: an evidence review for the U.S. Preventive services task force. Ann Int Med. 2008, 149: 565-582.

Sikorski J, Renfrew MJ, Pindoria S, Wade A: Support for breastfeeding mothers: a systematic review. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2003, 17: 407-417. 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2003.00512.x.

Dyson L, McCormick FM, Renfrew MJ: Interventions for promoting the initiation of breastfeeding. Cochrane database of systematic reviews issue 2. 2008, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons

Moore ER, Anderson GC, Bergman N: Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Cochrane database of systematic reviews issue 3. 2007, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons

Ahmed AH, Sands LP: Effect of Pre- and postdischarge interventions on breast feeding outcomes and weight gain among premature infants. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2010, 39: 53-63. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2009.01088.x.

Dennis C-L, Hodnett ED: Psychosocial and psychological interventions for treating postpartum depression. Cochrane database of systematic reviews issue 4. 2007, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons

Amorim Adegboye AR, Linne YM, Lourenco PMC: Diet or exercise, or both, for weight reduction in women after childbirth Cochrane database of systematic reviews issue 3. 2007, Chichester UK: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

Corcoran J, Pillai VK: Effectiveness of secondary pregnancy prevention programs: a meta-analysis. Res Soc Work Pract. 2007, 17: 5-18. 10.1177/1049731506291583.

Pinquart M, Tuebert D: Effects of parenting education with expectant and New parents: a meta analysis. J Fam Psychol. 2010, 24 (3): 316-327.

Vanderveen JA, Bassler D, Robertson CM, Kirpalani H: Early interventions involving parents to improve neurodevelopmental outcomes of premature infants: a meta-analysis. J Perinatol. 2009, 29: 343-351. 10.1038/jp.2008.229.

Alderdice F, McNeill J, Rowe R, Martin D, Dornan J: Inequalities in the reported offer and uptake of antenatal screening. Public Health. 2008, 122: 42-52. 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.05.004.

National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health: Antenatal care routine care for the healthy pregnant woman. 2008, London: RCOG Press

Wilson RD, on behalf of Genetics Committee of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada and The Motherisk Program, The Hospital for Sick Children Toronto, et al: Pre-conceptional vitamin/folic acid supplementation 2007: the Use of folic acid in combination with a multivitamin supplement for the prevention of neural tube defects and other congenital anomalies –guideline No. 201. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2007, 29 (12): 1003-1013.

Davies G, Wolfe L, Mottola M, MacKinnon C: Exercise in pregnancy and the post partum period –guideline No. 129. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2003, 25 (6): 516-522.

Department of Health: UK healthy lives, healthy people. 2010, London: HMSO

Olds D, Henderson CR, Chamberlin R, Tatelbaum R: Preventing Child Abuse and Neglect. Randomized Trial Nurse Home Visitation Pediatr. 1986, 78: 65-78.

CAS Google Scholar

Olds DL, Eckenrode J, Henderson CR, Kitzman H, Powers J, Cole R, Sidora K, Morris P, Pettitt LM, Luckeyet D: Long-term effects of home visitation on maternal life course and child abuse and neglect. Fifteen-year follow-up of a randomized trial. JAMA. 1997, 27: 278 (8): 637-643.

Biro MA: What has public health got to do with midwifery? Midwives' role in securing better health outcomes for mothers and babies. Women Birth. 2010, 24 (1): 17-23.

Jones L, Othman M, Dowswell T, Alfirevic Z, Gates S, Newburn M, Jordan S, Lavender T, Neilson T: Pain management for women in labour: an overview of systematic reviews (review) Cochrane database of systematic reviews issue 3. 2012, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/12/955/prepub

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all members of the Advisory Group for their contribution and guidance throughout the project. In addition, we would like to thank Midwifery 2020 for funding the original review and in particular, The Public Health Workstream Group who commissioned the original review.

Source of funding

The original review was funded by NHS Education for Scotland, Midwifery 2020, UK.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Nursing & Midwifery, Queen’s University Belfast, Medical Biology Centre, 97 Lisburn Road, Belfast, BT9 7BL, Ireland

Jenny McNeill, Fiona Lynn & Fiona Alderdice

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jenny McNeill .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Authors’ contributions

JM extracted and interpreted data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. FL conducted the searches of the literature, extracted and interpreted data and assisted with the manuscript. FA extracted and interpreted data and assisted with the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Authors’ original file for figure 1

Authors’ original file for figure 2, rights and permissions.

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

McNeill, J., Lynn, F. & Alderdice, F. Public health interventions in midwifery: a systematic review of systematic reviews. BMC Public Health 12 , 955 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-955

Download citation

Received : 05 April 2012

Accepted : 29 October 2012

Published : 08 November 2012

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-955

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Systematic review

- Public health

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 18 June 2019

Investigating midwives’ barriers and facilitators to multiple health promotion practice behaviours: a qualitative study using the theoretical domains framework