Eight tips to effectively supervise students during their Master's thesis

Jul 30, 2021 PhD

I am a fan of knowledge transfer between peers, teaching what I know to others and learning back from them. At University I frequently helped my fellow course mates with the material, so I was very interested in formally mentoring students when I started my PhD. Luckily my supervisor, who is really talented at this, agreed to let me help him with supervising some Master’s theses. In this article, also published as a Nature Career Column , I present eight lessons that I learned by watching him at work and trying on my own.

I supervised three Master’s students in the past year. One of them was quite good and independent, did not need a lot of guidance and could take care of most things on his own, while the other two required a fair amount of help from us, one of them even coming close to not graduating successfully. Dealing with the difficult situations is when I learned the most important lessons, but regardless of the ability of the students a common thread soon appeared.

But first, here’s a brief digression on how that happened. While I was writing a draft for this blog, I noticed an interesting article on Nature’s newsletter. While I was reading it, I felt its style was quite similar to what I usually aim for in this blog: use headlines to highlight the important points, and elaborate on those with a few paragraphs. I then noticed the author of that column was a PhD student, and I thought: “how comes she has an article there? Why can she do that? Can I do that?”. I quickly found how to do it , finished the draft and sent it to them, and, after eight rounds of review in the course of two months, the article was finally up! The editor was very responsive and we could iterate quickly on the manuscript, and the quality of the writing is so much better than what I had originally sent in. On the other hand, I sometimes felt the message was being warped a bit too much. After the editing process was finished I had to agree to an Embargo Period of six months during which Nature had the exclusive right of publishing the final version on their website. As those six months are now over, I am finally allowed to publish the final version here, too. Enjoy!

This is a post-peer-review, pre-copyedit version of an article published in Nature Career Column . The final authenticated version is available online at: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-02028-1 .

The lessons I learnt supervising master’s students for the first time

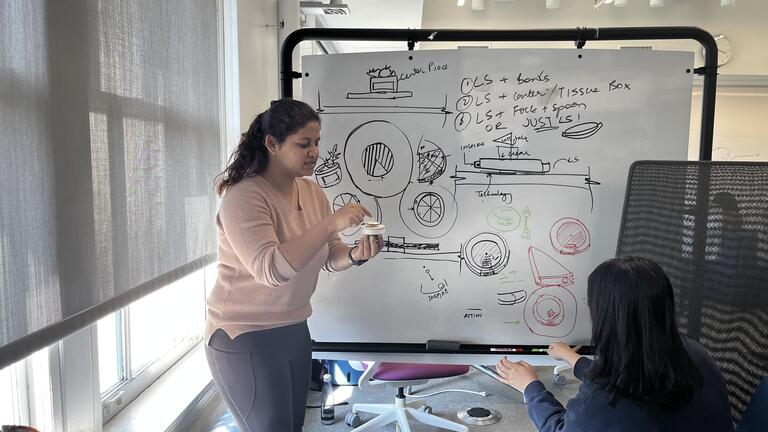

PhD student Emilio Dorigatti supported three junior colleagues during their degrees.

I started my PhD wanting to improve not only my scientific abilities, but also ‘soft skills’ such as communication, mentoring and project management. To this end, I joined as many social academic activities as I could find, including journal clubs, seminars, teaching assistance, hackathons, presentations and collaborations.

I am a bioinformatics PhD student at the Munich School for Data Science in Germany, jointly supervised by Bernd Bischl at the Ludwig Maximilian University Munich and Benjamin Schubert at the Helmholtz Centre Munich, the German Research Center for Environmental Health. When I went to them asking to gain some experience in communication and mentoring soft skills, they suggested that I co-supervise three of Benjamin’s master’s students.

At first, I felt out of my depth, so I simply sat in on their meetings and listened. After a few months, I began offering technical advice on programming. I then started proposing new analyses and contributions. Eventually I became comfortable enough to propose a new master’s project based on part of my PhD research; Benjamin and I are now interviewing candidates.

I gained a great deal from this experience and I am grateful to both of my supervisors for supporting me, as well as to the students for staying motivated, determined and friendly throughout. Here are some of the things I learnt about how to ensure smooth collaboration and a happy outcome for all of us.

Draft a project plan

With Benjamin and Bernd, I put together a project plan for each of the master’s students. Drafting a two-page plan that ended up resembling an extended abstract for a conference forced us to consider each project in detail and helped to ensure that it was feasible for a student to carry out in their last semester of study.

If you’re a PhD student supervising others, sit down with your own supervisor and agree on your respective responsibilities as part of the project plan. At first, you might want your supervisor to follow you closely to help keep the project on the right path, but as you gain more experience and trust, you might request more autonomy and independence.

Use the project plan to advertise the position and find a suitable student: share it online on the group’s website or on Twitter, as well as on the job board at your department. Advertise it to your students if you are teaching a related topic, and sit back and wait for applicants.

We structured the plans to include a general introduction to the research subject as well as a few key publications. We described the gap in the literature that the project aimed to close, with the proposed methodology and a breakdown of four or five tasks to be achieved during the project. My supervisors and I also agreed on and included specific qualifications that candidates should have, and formalities such as contact information, starting dates and whether a publication was expected at the end.

Benjamin and I decided to propose publishable projects, sometimes as part of a larger paper. We always list the student as one of the authors.

Meet your student regularly

I found that I met with most students for less than an hour per week, but some might require more attention. Most of the time, Benjamin joined the meeting, too. We started with the students summarizing what they had done the previous week and any issues they had encountered. We then had a discussion and brainstorming session, and agreed on possible next steps. I learnt that I do not need to solve all the student’s problems (it is their thesis, after all). Instead, Benjamin and I tried to focus on suggesting a couple of things they could try out. At the end of the meeting, we made sure it was clear what was expected for the next week.

We used the first few weeks to get the students up to speed with the topic, encouraging them to read publications listed in the plan, and a few others, to familiarize themselves with the specific methods that they would be working with. We also addressed administrative matters such as making sure that the students had accounts to access computational resources: networks, e-mail, Wi-Fi, private GitHub repositories and so on.

Encourage regular writing

Good writing takes time, especially for students who are not used to it, or who are writing in a foreign language. It is important to encourage them to write regularly, and to keep detailed notes of what should be included in the manuscript, to avoid missing key details later on. We tried to remind our students frequently how the manuscript should be structured, what chapters should be included, how long each should be, what writing style was expected, what template to use, and other specifics. We used our meetings to provide continuous feedback on the manuscript.

The first two to four weeks of the project are a good time to start writing the first chapters, including an introduction to the topic and the background knowledge. We suggested allocating the last three or four weeks to writing the remaining chapters — results and conclusions — ensuring that the manuscript forms a coherent whole, and preparing and rehearsing the presentation for the oral examination.

Probe for correct understanding

In our weekly meetings, or at other times when I was teaching, I quickly realized that asking ‘did you understand?’ or ‘is that OK?’ every five minutes is not enough. It can even be counterproductive, scaring away less-assertive students.

I learnt to relax a little and take a different approach: when I explained something, I encouraged the students to explain it back in their own words, providing detailed breakdowns of a certain task, anticipating possible problems, and so on.

Ultimately, this came down to probing for understanding of the science, rather than delivering a lecture or grilling an interviewee. Sometimes this approach helps when a student thinks they fully understand something but actually don’t. For example, one of our students was less experienced in programming than others, so for more difficult tasks, we broke the problem down and wrote a sketch of the computer code that they would fill in on their own during the week.

Adapt supervision to the student

Each student requires a different type of supervision, and we tried to adapt our styles to accommodate that. That could mean using Trello project-management boards or a shared Google Doc to record tasks; defining tasks in detail and walking through them carefully; or taking extra time to explain and to fill knowledge gaps. I tried to be supportive by reminding students that they could always send an e-mail if they were stuck on a problem for too long. One of the students found it very helpful to text brief updates outside of scheduled meetings, as a way to hold themselves accountable.

Sometimes, if we felt a student needed to be challenged, we proposed new tasks that were not in the original plan or encouraged them to follow their interest, be it diving into the literature or coming up with further experiments and research questions.

One student conducted a literature review and summarized the pros and cons of the state-of-the-art technology for a follow-up idea we had. That saved some time when we picked up the project after the student left; they learnt lots of interesting things; and the discussion section of the manuscript was much more interesting as a result.

When things go badly, make another plan

Not all projects can be successful, despite your (and your student’s) best efforts. So, as part of each project, my supervisors and I prepared a plan B (and C), working out which tasks were essential and which were just a nice addition. This included a simpler research question that required less work than the original. The initial plan for one of our projects was to compare a newly proposed method with the usual way of doing things, but the new method turned out to be much more difficult than anticipated, so we decided not to do the comparison, and just showed how the new method performed.

Halfway through the project is a good time to evaluate how likely it is that the thesis will be handed in on time and as originally planned. The top priority is to help the student graduate. That might entail either forgoing some of the tasks planned at the beginning, or obtaining an extension of a few months if possible.

Have a final feedback round

After the oral examinations, Benjamin and I met to decide the students’ final grades on the basis of the university’s rubric. We then met the students one last time to tell them our decision, going through each item in the rubric and explaining the motivation for the score we had given. We tried to recall relevant events from the past months to make each student feel the grading was fair.

We also remembered to ask the student for feedback on our supervision and to suggest things they thought we could do better.

Lastly, I encouraged those students to apply for open positions in our lab, and offered to write recommendation letters for them.

Supervising DPhil and Masters dissertations

Guidance on making contingency plans for if research is disrupted during the pandemic.

Supervising postgraduate research students often requires flexibility as their research changes direction or they identify new questions to consider, for example. The current situation presents unique challenges that have seen research students being unable to gather data if laboratories, archives, or fieldwork sites have been closed. This highlights the importance of making individual contingency plans. Even as laboratories and archives reopen, supervisors and students need to be ready, should changes in access arise.

Pedagogical guidance

Technical guidance, useful links, related oxford examples.

The greatest challenge comes during the research process and it would be advisable to have a conversation with your students about challenges they might face in the coming months and years. It remains particularly important to clearly communicate expectations about work set, working practices, and deadlines or doctoral milestones, for example, and to assess how the pandemic might affect your students’ abilities to meet them.

If research and data collection has been suspended due to the pandemic but students are wanting to continue to work, focused tasks can help develop analytical and writing skills that the student can apply once they can resume their research. For example, you might want to present them with a set of data closely related to their own with questions for them to tackle, ask them to work on a particular section of their draft or a particular aspect of their writing, or, if they are at the beginning of their research, you might encourage them to develop other academic skills such as writing book reviews or synthesising conclusions from a collection of articles.

Research students often complain they feel isolated even in more normal times. Feelings of isolation may escalate other hurdles such as limited progress so try to maintain regular contact and encourage them to meet with other students and academics, even if only via video conferencing. With many students facing similar situations, a face to face or online gathering of a group of research students can be an effective way to problem-solve and can help to create support networks for students. You might want to set up a journal club to bring postdocs and research students together or schedule sessions for students to share their work in progress.

Platforms such as Teams make shifting from face to face to remote teaching fairly straightforward, but it is worth bearing in mind that staff and student feedback from Trinity term 2020 has noted that remote teaching is more tiring and that shorter sessions are more effective.

Microsoft Teams (often referred to as MS Teams or simply Teams ) allows you to schedule live meetings with video and screensharing.

Teams also provides functionality for sharing documents, as it is part of Nexus Office365. These documents can be collaborated on by multiple people simultaneously. It can be effective to work collaboratively on a single document during a Teams meeting.

The chat functionality in Teams also provides a useful, less formal way of interacting with participants. The chat thread is automatically saved for later reference via the Teams chat channel.

- You might find Scenario 2 ‘Inclusive and flexible tutorials’ helpful.

- The CTL’s DPhil Supervision in Humanities and Social Sciences and DPhil Supervision in Sciences - further guidance on supervising doctoral students

- Getting started with Microsoft Teams

- Nexus 365: face-to-face course (IT Learning Centre)

- Microsoft Teams help and learning portal

- CATME smarter teamwork - a tool kit which helps you prepare students to function effectively in teams and supports academics as they manage their students’ team experiences

- Molteno, O. (2017) How to build an engaged online learning community [Blog], GetSmarter Research Hub, 6 March 2017

- Microsoft Teams

- Postgraduate

SEE ALL RESOURCES FOR FLEXIBLE AND INCLUSIVE TEACHING

Helpdesk service

Resources for flexible and inclusive teaching

First meeting with your dissertation supervisor: What to expect

The first meeting with your dissertation supervisor can be a little intimidating, as you do not know what to expect. While every situation is unique, first meetings with a dissertation supervisor often centre around getting to know each other, establishing expectations, and creating work routines.

Why a good relationship with a dissertation supervisor matters

Getting to know each other during the first meeting, getting to know the work environment during the first meeting, establishing a meeting and communication schedule, discussing your research idea with your dissertation supervisor, discussing expectations with your dissertation supervisor.

Writing a dissertation is an exciting but also intimidating part of being a bachelor’s, master’s or PhD student. A dissertation is often the culmination of several years of higher education, and the last step before graduating.

What is important to know is that the relationship that you establish with your supervisor can be a crucial factor in completing a successful dissertation.

A better relationship often results in better and timely completion of a dissertation. This finding is backed up by science. This study , for instance, points out that student-supervisor relationships strongly influence the quality, success or failure of completing a PhD (on time).

Good communication with a dissertation supervisor is key to advancing your research, discussing roadblocks, and incorporating feedback and advice.

Commonly experienced challenges in student-supervisor relationships, on the other hand, are “different expectations, needs and ways of thinking and working” (Gill and Burnard, 2008, p. 668).

Therefore, getting acquainted with each other to set a foundation for the upcoming collaboration is often what first meetings with dissertation supervisors are (and should be) about.

Many first meetings with a dissertation supervisor include a considerable amount of ‘small talk’. Thus, you can expect to engage in a casual conversation to get acquainted.

This conversation tends to look different based on whether you already know your dissertation supervisor, or whether you have never met them before. It could also be that you had a talk with your dissertation supervisor during a formal interview stage, but never talked informally.

Common questions to expect are:

- How are you doing?

- Did you find adequate housing, and did the (international) move go well?

- Did you bring a partner, spouse or family to a new country or city?

- What do you like to do in your free time?

- Where and what did you study before?

- How did you experience your degree programme so far?

- What courses did you enjoy?

- How did you come up with your dissertation topic?

- What are your ambitions for this thesis?

- What are your expectations and goals for both the thesis process?

- What do you want to do after graduating?

You may also like: Getting the most out of thesis supervision meetings

PhD students who start their dissertation are often introduced to their lab, research group or department during the first meeting.

It is not uncommon for the dissertation supervisor to walk around with the new student and introduce him or her to colleagues and supporting staff.

Getting to know your (new) work environment is less common for students who write a dissertation to complete their master’s degrees. Though in some cases, they conduct their master thesis research as part of a lab or existing research project, and will be introduced there as well.

There may also be a discussion about accessing an institutional email address or online work environment as a dissertation student. And any questions that are important to answer to kick off the dissertation process.

During the first meeting, it is very useful for both the student and the dissertation supervisor to discuss their collaboration for the coming months.

This particularly includes agreements on meetings and the frequency of communication. Even if your dissertation supervisor does not raise these issues during the first meeting, it can be helpful to raise them yourself.

Establishing a meeting schedule, or at least discussing how often you are planning to meet, how regularly, and within what time intervals, can reduce a lot of stress and uncertainty.

It can also be very valuable to talk about the frequency of communication. Does your dissertation supervisor appreciate a weekly summary of your progress? Or are you only supposed to reach out when you hit a roadblock?

Furthermore, what are the best ways to communicate? For instance, does your supervisor prefers emails? If so, check out some sample emails to a thesis supervisor ! Or does your supervisor prefer you to collect all your questions until the next supervision meeting, putting them on the meeting agenda?

While you can expect a lot of Smalltalk, planning, and organisational issues to dominate the first meeting with your dissertation supervisor, it is common to also chat about your research idea.

But don’t worry! Supervisors tend to be aware that you are just at the beginning of the dissertation process. Usually, they don’t expect you to provide a fully-fledged research proposal or a formal presentation.

However, be prepared to share your initial thoughts and ideas. Additionally, be prepared to explain why you are interested in the topic and how you roughly anticipate conducting your research and writing your dissertation.

Based on this information, the dissertation supervisor can already point you in the right direction, suggest relevant literature, or connect you with other students or colleagues who work on similar issues.

It is normal to feel slightly lost during the first weeks of working on your dissertation.

However, to keep this feeling to a minimum, it can be extremely helpful to create concrete steps and plans with your dissertation supervisor for the first weeks.

Expectations differ from supervisor to supervisor. Some may just expect you to simply get used to your work environment, read a lot and explore theories that are relevant to your dissertation. Others may want to see the first results in terms of a literature review or research proposal.

Thus, make sure to discuss expectations for the upcoming weeks during the first meeting with your dissertation supervisor. It will prevent you from overthinking what you should do.

Elsewhere, I have written a guide for first-year PhD students with some directions and advice . As a PhD student, you can use this guide as an inspiration and starting point to discuss your own supervisor’s expectations.

If you are writing a master thesis, your timeframe will be much shorter. Thus, it is even more important to define deadlines and milestones with your dissertation supervisor as soon as possible. The first meeting lends itself to making this plan.

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox!

Subscribe and receive Master Academia's quarterly newsletter.

How many conferences postgrads should attend

10 things to do when you feel like your dissertation is killing you, related articles.

How to prepare your viva opening speech

Theoretical vs. conceptual frameworks: Simple definitions and an overview of key differences

3 inspiring master’s thesis acknowledgement examples

75 linking words for academic writing (+examples)

Real Learning Opportunities at Business School and Beyond pp 211–222 Cite as

Master Thesis Supervision

- Judith H. Semeijn 5 ,

- Janjaap Semeijn &

- Kees J. Gelderman

852 Accesses

1 Citations

Part of the book series: Advances in Business Education and Training ((ABET,volume 2))

An increasing number of educators are actively involved in master thesis supervision as part of their daily responsibilities. Master of Science degrees are becoming increasingly popular, with a master thesis required for the completion of the degree program. As a result, the supervisory staff involved in the supervision process at universities and institutes of higher learning is broadening and includes people with limited supervisory experience.

- Master Thesis

- Student Evaluation

- Blended Learning

- Supervision Process

- Thesis Process

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Allen, G. R. (1973). The graduate students’ guide to theses and dissertations: A Practical manual for writing and research . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Google Scholar

Arbaugh, J. B. (2008). Introduction: Blended Learning: Research and Practice. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 7 (1).

Bonk, C. J., & Graham, C. R. (2005). The handbook of blended learning: Global perspectives, local designs . New York: Pfeiffer.

BKO. (2006). Retrieved on August 18, 2008 http://www.iso.nl/Portals/0/documenten/Thema/Basiskwalificatie%20Onderwijs%202006.pdf

Burgess, R. G., Pole, C. J., & Hockey, J. (1994). Strategies for managing and supervising the Social Science PhD. In R. Burgess (Ed.), Postgraduate education and training in the social sciences: Processes and products (pp. 12–33). London: Kingsley.

Buswell, G. T. (1932). The doctor’s dissertation. The Journal of Higher Education, 3 (3).

Cunningham, S. J. (2004). How to write a thesis. Journal of Orthodontics, 31 , 144–148.

Article Google Scholar

Delamont, S., Atkinson, P., & Parry, O. (2001). Supervising the PhD. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Dillon, M. J., & Malott, R. W. (1981). Supervising masters theses and doctoral dissertations. Teaching and Psychology, 8 (3), 195–202.

Dochy, F., Segers, M., Van den Bossche, P., & Gijbels, D. (2003). Effects of problem-based learning: A meta-analysis. Learning and Instruction, 13 , 533–568.

Garcia, M. E., Mallot, R. W., & Brethower, D. (1988). A system of thesis and dissertation supervision: Helping graduate students succeed. Teaching of Psychology, 7 , 89–92.

Gijselaers, W. H. (1996, Winter). Connecting problem-based practices with educational theory. In L. Wilkerson & W. Gijselaers (Eds.), Bringing problem-based learning to higher education: Theory and practice . New Directions in Teaching and Learning Series. No. 68. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Hauck, A. J., & Chen, C. (1998). Using action research as a viable alternative for graduate theses and dissertations in construction management. Journal of Construction Education, 3 (2).

Holligan, C. (2005). Fact and fiction: A case history of doctoral supervision. Educational Research, 47 (3).

Hwang, A., & Arbaugh, J. B. (2006). Virtual and traditional feedback-seeking behaviors: Underlying competitive attitudes and consequent grade performance. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 4 , 1–28.

Long, T. J., Convey, J. J., & Chwalek, A. R. (1985). Completing dissertations in the behavioral sciences . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Marsh, H. W., Rowe, K. J., & Martin, A. (2002). PhD students’ evaluations of research supervision: Issues, complexities, and challenges in a nationwide Australian experiment in Benchmarking Universities. The Journal of Higher Education, 73 (3)

Mauch, J. E., & Birch, J. W. (1998). Guide to the successful thesis and dissertation. Conception to publication: A handbook for students and faculty (4th ed.). New York: Marcel Dekker Inc.

Nederlands-Vlaamse Accreditatie Organisatie/NVAO. (2003). Accreditatiekader bestaande opleidingen hoger onderwijs, February. Referentie compleet?

Picciano, A. G., & Dziuban, C. D. (Eds.). (2007). Blended learning: Research perspectives. Needham, MA: Sloan Consortium.

Rau, A. (2005). Supervision: A Foucaultian exploration of institutional and interpersonal power relations between postgraduate supervisors, their students and the university domain . PhD thesis, Rhodes University.

Romme, G. L. (2003). Organizing education by drawing on organization studies. Organization Studies, 24 (5).

Ryan, Y., & Zuber-Skerritt, O. (Eds.). (1999). Supervising postgraduates from non-English speaking backgrounds. Buckingham: The Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press.

Savin-Baden, M., & Major, C. H. (2004). Foundations of problem-based learning: Illuminating perspectives. Maidenhead: SRHE/Open University Press.

Semeijn, J. H., Velden, R. van der, Heijke, H., Vleuten, C. van der, & Boshuizen, H. (2006). Competence indicators in academic education and early labour market success of graduates in health sciences. Journal of Work and Education, 19 (4).

Schmidt, H., Vermeulen, L., & Van der Molen, H. T.,(2004). Longterm effects of problem-based learning: A comparison of competencies acquired by graduates of a problem-based and a conventional medical school. Medical Education, 40 (2).

Teitelbaum, H. (1998). How to write a thesis. Prentice Hall & IBD, 1998.

Thomas, C. (1995). Helping students complete master’s theses through active supervision. Journal of Management Education, 19 (2).

Tinkler, P., & Jackson, C. (2000). Examining the doctorate, institutional policy and the PhD examination process in Britain. Studies in Higher education, 25 (2).

Weber, B., & Hertel, G. (2007). Motivation gains of inferior group members: Ameta-analytical review. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93 (6).

Zuber-Skerrit, O., & Fletcher, M. (2007). The quality of an action research thesis in the social sciences. Quality Assurance in Education, 15 (4).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Management, Open Universiteit Nederland, Valkenburgerweg 177, 6419, Heerlen, AT, The Netherlands

Judith H. Semeijn

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Judith H. Semeijn .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Business Communic. & Language Studies, EDHEC Business School, 58 Rue du Port, 59046, Lille, France

Inst. Education & Information Sciences, University of Antwerp, Venusstraat 35, 2000, Antwerpen, Belgium

David Gijbels

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2009 Springer Science+Business Media B.V.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Semeijn, J.H., Semeijn, J., Gelderman, K.J. (2009). Master Thesis Supervision. In: Daly, P., Gijbels, D. (eds) Real Learning Opportunities at Business School and Beyond. Advances in Business Education and Training, vol 2. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2973-7_14

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2973-7_14

Publisher Name : Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN : 978-90-481-2972-0

Online ISBN : 978-90-481-2973-7

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Teaching & Learning

- Education Excellence

- Professional development

- Case studies

- Teaching toolkits

- MicroCPD-UCL

- Assessment resources

- Student partnership

- Generative AI Hub

- Community Engaged Learning

- UCL Student Success

Research and project supervision (all levels): an introduction

Supervising projects, dissertations and research at UCL from undergraduate to PhD.

1 August 2019

Many academics say supervision is one of their favourite, most challenging and most fulfilling parts of their job.

Supervision can play a vital role in enabling students to fulfil their potential. Helping a student to become an independent researcher is a significant achievement – and can enhance your own teaching and research.

Supervision is also a critical element in achieving UCL’s strategic aim of integrating research and education. As a research-intensive university, we want all students, not just those working towards a PhD, to engage in research.

Successful research needs good supervision.

This guide provides guidance and recommendations on supervising students in their research. It offers general principles and tips for those new to supervision, at PhD, Master’s or undergraduate level and directs you to further support available at UCL.

What supervision means

Typically, a supervisor acts as a guide, mentor, source of information and facilitator to the student as they progress through a research project.

Every supervision will be unique. It will vary depending on the circumstances of the student, the research they plan to do, and the relationship between you and the student. You will have to deal with a range of situations using a sensitive and informed approach.

As a supervisor at UCL, you’ll help create an intellectually challenging and fulfilling learning experience for your students.

This could include helping students to:

- formulate their research project and question

- decide what methods of research to use

- become familiar with the wider research community in their chosen field

- evaluate the results of their research

- ensure their work meets the necessary standards expected by UCL

- keep to deadlines

- use feedback to enhance their work

- overcome any problems they might have

- present their work to other students, academics or interested parties

- prepare for the next steps in their career or further study.

At UCL, doctoral students always have at least two supervisors. Some faculties and departments operate a model of thesis committees, which can include people from industry, as well as UCL staff.

Rules and regulations

Phd supervision.

The supervision of doctoral students’ research is governed by regulation. This means that there are some things you must – and must not – do when supervising a PhD.

- All the essential information is found in the UCL Code of Practice for Research Degrees .

- Full regulations in the UCL Academic Manual .

All staff must complete the online course Introduction to Research Supervision at UCL before beginning doctoral supervision.

Undergraduate and Masters supervision

There are also regulations around Master’s and undergraduate dissertations and projects. Check with the Programme Lead, your Department Graduate Tutor or Departmental Administrator for the latest regulations related to student supervision.

You should attend other training around research supervision.

- Supervision training available through UCL Arena .

Doctoral (PhD) supervision: introducing your student to the university

For most doctoral students, you will often be their main point of contact at UCL and as such you are responsible for inducting them into the department and wider community.

Check that your student:

- knows their way around the department and about the facilities available to them locally (desk space, common room, support staff)

- has attended the Doctoral School induction and has received all relevant documents (including the Handbook and code of practice for graduate research degrees )

- has attended any departmental or faculty inductions and has a copy of the departmental handbook.

Make sure your student is aware of:

- key central services such as: Student Support and Wellbeing , UCL Students' Union (UCLU) and Careers

- opportunities to broaden their skills through UCL’s Doctoral Skills Development Programme

- the wider disciplinary culture, including relevant networks, websites and mailing lists.

The UCL Good Supervision Guide (for PhD supervisors)

Establishing an effective relationship

The first few meetings you have with your student are critical and can help to set the tone for the whole supervisory experience for you and your student.

An early discussion about both of your expectations is essential:

- Find out your student’s motivations for undertaking the project, their aspirations, academic background and any personal matters they feel might be relevant.

- Discuss any gaps in their preparation and consider their individual training needs.

- Be clear about who will arrange meetings, how often you’ll meet, how quickly you’ll respond when the student contacts you, what kind of feedback they’ll get, and the norms and standards expected for academic writing.

- Set agendas and coordinate any follow-up actions. Minute meetings, perhaps taking it in turns with your student.

- For PhD students, hold a meeting with your student’s other supervisor(s) to clarify your expectations, roles, frequency of meetings and approaches.

Styles of supervision

Supervisory styles are often conceptualized on a spectrum from laissez-faire to more contractual or from managerial to supportive. Every supervisor will adopt different approaches to supervision depending on their own preferences, the individual relationship and the stage the student is at in the project.

Be aware of the positive and negative aspects of different approaches and styles.

Reflect on your personal style and what has prompted this – it may be that you are adopting the style of your own supervisor, or wanting to take a certain approach because it is the way that it would work for you.

No one style fits every situation: approaches change and adapt to accommodate the student and the stage of the project.

However, to ensure a smooth and effective supervision process, it is important to align your expectations from the very beginning. Discuss expectations in an early meeting and re-visit them periodically.

Checking the student’s progress

Make sure you help your student break down the work into manageable chunks, agreeing deadlines and asking them to show you work regularly.

Give your student helpful and constructive feedback on the work they submit (see the various assessment and feedback toolkits on the Teaching & Learning Portal ).

Check they are getting the relevant ethical clearance for research and/or risk assessments.

Ask your student for evidence that they are building a wider awareness of the research field.

Encourage your student to meet other research students and read each other’s work or present to each other.

Encourage your student to write early and often.

Checking your own performance

Regularly review progress with your student and any co-supervisors. Discuss any problems you might be having, and whether you need to revise the roles and expectations you agreed at the start.

Make sure you know what students in your department are feeding back to the Student Consultative Committee or in surveys, such as the Postgraduate Research Experience Survey (PRES) .

Responsibility for the student’s research project does not rest solely on you. If you need help, talk to someone more experienced in your department. Whatever the problem is you’re having, the chances are that someone will have experienced it before and will be able to advise you.

Continuing students can often provide the most effective form of support to new students. Supervisors and departments can foster this, for example through organising mentoring, coffee mornings or writing groups.

Be aware that supervision is about helping students carry out independent research – not necessarily about preparing them for a career in academia. In fact, very few PhD students go on to be academics.

Make sure you support your student’s personal and professional development, whatever direction this might take.

Every research supervision can be different – and equally rewarding.

Where to find help and support

Research supervision web pages from the UCL Arena Centre, including details of the compulsory Research Supervision online course.

Appropriate Forms of Supervision Guide from the UCL Academic Manual

the PhD diaries

Good Supervision videos (Requires UCL login)

The UCL Doctoral School

Handbook and code of practice for graduate research degrees

Doctoral Skills Development programme

Student skills support (including academic writing)

Student Support and Wellbeing

UCL Students' Union (UCLU)

UCL Careers

External resources

Vitae: supervising a docorate

UK Council for Graduate Education

Higher Education Academy – supervising international students (pdf)

Becoming a Successful Early Career Researcher , Adrian Eley, Jerry Wellington, Stephanie Pitts and Catherine Biggs (Routledge, 2012) - book available on Amazon

This guide has been produced by the UCL Arena Centre for Research-based Education . You are welcome to use this guide if you are from another educational facility, but you must credit the UCL Arena Centre.

Further information

More teaching toolkits - back to the toolkits menu

Research supervision at UCL

UCL Education Strategy 2016–21

Connected Curriculum: a framework for research-based education

The Laidlaw research and leadership programme (for undergraduates)

[email protected] : contact the UCL Arena Centre

Download a printable copy of this guide

Case studies : browse related stories from UCL staff and students.

Sign up to the monthly UCL education e-newsletter to get the latest teaching news, events & resources.

Education events

Funnelback feed: https://search2.ucl.ac.uk/s/search.json?collection=drupal-teaching-learn... Double click the feed URL above to edit

- Help & FAQ

Participatory alignment: a positive relationship between educators and students during online masters dissertation supervision

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article › Research › peer-review

The expansionist nature of the higher education sector has led to an increase in the provision of online Masters programmes. Many of these programmes are offered part-time attracting working professionals. The dissertation component that can be the culmination of many of these degrees is largely unexplored. A constructivist grounded theory investigation of the relationship between online Masters dissertation students and their supervisors was undertaken. Five supervisors identified a recent graduate and each were interviewed independently; interviews were undertaken online and audio-recorded. Transcripts were analysed and resultant themes considered in terms of establishing, and then maintaining, the relationship. A model of participatory alignment is proposed to describe the relationship that developed online in this group of supervisors and graduates, based on aligned expectations and behaviours, building on the idea of supervision as a partnership. We propose there is a zone of participatory alignment with both under and over-alignment becoming potentially problematic.

- dissertation

- Online supervision

- postgraduate qualifications

- professional education

Access to Document

- 10.1080/13562517.2020.1744129

Other files and links

- Link to publication in Scopus

T1 - Participatory alignment

T2 - a positive relationship between educators and students during online masters dissertation supervision

AU - Aitken, Gillian

AU - Smith, Kelly

AU - Fawns, Tim

AU - Jones, Derek

N1 - Funding Information: With thanks to the anonymous reviewers whose comments led to significant improvements to this work. Publisher Copyright: © 2020 Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group.

N2 - The expansionist nature of the higher education sector has led to an increase in the provision of online Masters programmes. Many of these programmes are offered part-time attracting working professionals. The dissertation component that can be the culmination of many of these degrees is largely unexplored. A constructivist grounded theory investigation of the relationship between online Masters dissertation students and their supervisors was undertaken. Five supervisors identified a recent graduate and each were interviewed independently; interviews were undertaken online and audio-recorded. Transcripts were analysed and resultant themes considered in terms of establishing, and then maintaining, the relationship. A model of participatory alignment is proposed to describe the relationship that developed online in this group of supervisors and graduates, based on aligned expectations and behaviours, building on the idea of supervision as a partnership. We propose there is a zone of participatory alignment with both under and over-alignment becoming potentially problematic.

AB - The expansionist nature of the higher education sector has led to an increase in the provision of online Masters programmes. Many of these programmes are offered part-time attracting working professionals. The dissertation component that can be the culmination of many of these degrees is largely unexplored. A constructivist grounded theory investigation of the relationship between online Masters dissertation students and their supervisors was undertaken. Five supervisors identified a recent graduate and each were interviewed independently; interviews were undertaken online and audio-recorded. Transcripts were analysed and resultant themes considered in terms of establishing, and then maintaining, the relationship. A model of participatory alignment is proposed to describe the relationship that developed online in this group of supervisors and graduates, based on aligned expectations and behaviours, building on the idea of supervision as a partnership. We propose there is a zone of participatory alignment with both under and over-alignment becoming potentially problematic.

KW - dissertation

KW - Online supervision

KW - postgraduate qualifications

KW - professional education

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=85082485289&partnerID=8YFLogxK

U2 - 10.1080/13562517.2020.1744129

DO - 10.1080/13562517.2020.1744129

M3 - Article

AN - SCOPUS:85082485289

SN - 1356-2517

JO - Teaching in Higher Education

JF - Teaching in Higher Education

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Journal of Public Health

- About the Faculty of Public Health of the Royal Colleges of Physicians of the United Kingdom

- Editorial Board

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Acknowledgements, supplementary data.

- < Previous

Characteristics of good supervision: a multi-perspective qualitative exploration of the Masters in Public Health dissertation

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Srinivasa Vittal Katikireddi, Jacqueline Reilly, Characteristics of good supervision: a multi-perspective qualitative exploration of the Masters in Public Health dissertation, Journal of Public Health , Volume 39, Issue 3, September 2017, Pages 625–632, https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdw107

- Permissions Icon Permissions

A dissertation is often a core component of the Masters in Public Health (MPH) qualification. This study aims to explore its purpose, from the perspective of both students and supervisors, and identify practices viewed as constituting good supervision.

A multi-perspective qualitative study drawing on in-depth one-to-one interviews with MPH supervisors ( n = 8) and students ( n = 10), with data thematically analysed.

The MPH dissertation was viewed as providing generic as well as discipline-specific knowledge and skills. It provided an opportunity for in-depth study on a chosen topic but different perspectives were evident as to whether the project should be grounded in public health practice rather than academia. Good supervision practice was thought to require topic knowledge, generic supervision skills (including clear communication of expectations and timely feedback) and adaptation of supervision to meet student needs.

Two ideal types of the MPH dissertation process were identified. Supervisor-led projects focus on achieving a clearly defined output based on a supervisor-identified research question and aspire to harmonize research and teaching practice, but often have a narrower focus. Student-led projects may facilitate greater learning opportunities and better develop skills for public health practice but could be at greater risk of course failure.

The Masters in Public Health (MPH) was historically the first opportunity to gain the core knowledge and expertise demanded of the discipline, 1 with a dissertation commonly required. Despite this, there is a lack of clarity about the purpose of the MPH dissertation and its necessity long questioned. 2

The modern MPH reaches a range of students with varied disciplines and backgrounds—more so than was historically the case in the UK. This echoes the growing diversity within the public health workforce. 3 – 6 The prior disciplines of students, therefore, now span the breadth of the arts, humanities, sciences as well as the world of healthcare. 3 This increased diversity has allowed a genuinely inter-disciplinary and increasingly international approach which is a necessity for future public health practice and research. 7 – 9

Despite the broad use of the MPH dissertation in many universities, there is limited research on the views of students and supervisors. 10 – 13 Research is necessary since the higher education literature highlights the importance of subject and qualification level in influencing supervision and research–teaching linkages, 14 – 16 with the Master's dissertation particularly regarded as an ill-defined ‘chameleon’. 17 The pedagogical literature draws attention to the benefits of making the processes of postgraduate degree supervision explicit for both supervisors and students. 18 Given the growing diversity of students served by the MPH, and the large number of supervisors, there is a risk that a shared understanding may be lacking. We explored the purpose of the MPH dissertation from the perspective of both students and supervisors, and identify practices viewed as constituting good supervision.

To gain an in-depth understanding of the range of views, a multi-perspective qualitative interview study 19 was undertaken with staff and students. This design explicitly allows diversity in participants’ views to be sought (including comparisons between staff and students). The stated purpose of the MPH dissertation at this institution is to provide an opportunity ‘to carry out an original piece of work’ and projects run from January to August annually. It could involve primary research, analysis of secondary data or a (semi-systematic) literature review.

Potential staff participants were chosen on the basis of their University website profiles, supplemented by snowball sampling. A purposive sample aiming for diversity of supervisor experience (senior staff and junior staff), parent discipline (clinical, social sciences and statistics) and methodological expertise (quantitative and qualitative) was sought. Potential participants were initially sent an information leaflet by e-mail and invited to participate, with a maximum of three e-mails in the case of non-response.

Purposive sampling of students sought diversity of disciplinary background (healthcare related, non-healthcare related), country of origin (UK, international student) and dissertation methodology (quantitative and qualitative). Students supervised by J.R. were ineligible for interview.

Informed consent was obtained at the interview and recorded in writing. Topic guides, informed by existing literature and advice from an expert in pedagogical research (see Acknowledgements), were created to help structure interviews, with coverage of core topics included in both staff and student interviews, but further questions tailored for each set of participants (see Supplementary Appendix ). Staff interviews were carried out by S.V.K. (at the time, a public health specialist registrar who had not supervised MPH dissertations) and student interviews by J.R. (an MPH course university teacher who has supervised many students). All data were collected approximately midway through the dissertation period, so students were still accessible for interviews. Interviews were audio recorded and typically lasted 30–45 min.

Following verbatim transcription, interview data were read repeatedly and analysis proceeded in keeping with the principles of grounded theory. 20 , 21 Inductive thematic coding was conducted by S.V.K. and J.R., with initial descriptive codes created and subsequently recoded to characterize emergent themes. The principle of the constant-comparative method was used to help identify explanations for patterns within the data while also paying attention to contradictory data.

The study was approved by the University of Glasgow College of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine research ethics committee.

Of the 10 staff approached, all agreed to be interviewed but a suitable time could not be arranged with 2, resulting in 8 staff participants (and good sample diversity achieved). Seventeen students were invited to participate and 10 interviewed, with the intended diversity achieved. No further descriptive details or disaggregation of quotations beyond ‘Supervisor’ or ‘Student’ are provided, to ensure anonymity.

Below, we present key emergent themes: first, briefly outlining interviewees’ views on reasons for undertaking the MPH; second, more detailed consideration of the MPH dissertation's purpose in particular; third, perspectives on dissertation supervision and finally, identified tensions that impact on the supervision process. In the Discussion, we build on these findings to develop two putative ideal types to describe alternative dissertation supervision approaches.

The purpose of the MPH

Supervisor: And I know that some of the students come because it's part of their career progression. I think some of them are just really interested in it [public health] and it's a chance to be really interested in something for a year. I guess they're all looking to attain a recognisable qualification which marks them out as having a certain level of knowledge and perhaps some skill, some research skill. […] some of them are looking to get that then to get into public health.

Supervisor: Well I think traditionally it's [the MPH has] been a kind of broad-based preparation for the world of Public Health, for people to take up the types of jobs that they do in fact tend to take up once they graduate from here. So, while it's a fairly academic programme a lot of the posts in Public Health do tend to be fairly academic.

The purpose of the dissertation

While respondents acknowledged that most students would not conduct comparable future research, some saw striking similarity between public health practice and research (Table 1 d). Others also saw the insight experienced from carrying out research as a way to foster improved long-term communication between academia and practice. An alternative view highlighted tailoring the dissertation to the practice environment (Table 1 e) but other respondents cautioned that projects originating from public health practice were often ill-suited, tending to be too broad and not adequately rigorous. The risk that students may be expected to carry out too large a project, as a result of unrealistic employer pressure, was expressed but tempered by an appreciation that employers may reasonably expect some benefits if they have funded students.

Another much debated purpose, and less so students, was the potential for dissertation research to result in academic publications. At best, this was seen as helping align research and teaching responsibilities for supervisors while benefiting students by helping improve their skills and CV (Table 1 f). However, potential benefits to science and the supervisor's career were not accepted uncritically with one supervisor commenting: ‘the reality is—I don't need extra low-grade publications’ . While there was an acknowledgement that publication may constitute a ‘win-win’ , some interviewees felt it might be impossible to achieve as students (and supervisors) may not have the requisite time and patience to follow-up on dissertation work (Table 1 g).

Others expressed concerns about encouraging students to publish or seeing it as a goal to be pursued. If a publication was being considered by the supervisor, it was felt this may limit the student's potential for learning as a narrow project predefined by the supervisor is more likely (Table 1 h). In addition, it was felt to be a more amenable model for dissertations using already collected data; hence, of more relevance for some (primarily quantitative) research. Students may, therefore, be less likely to learn and gain experience in primary data collection, a skill perceived as valuable by some.

Good supervision practice

Supervisors and students broadly agreed on a number of key elements for good supervision. First, it was felt necessary for supervisors to have good knowledge about what constitutes a dissertation and therefore be able to guide students through the process (Table 2 b). Furthermore, having expert knowledge of the topic they were supervising and technical expertise on the research methods were viewed as important. While prior topic knowledge was not always considered essential, supervisors indicated that they would endeavour to learn about it so they could guide the student appropriately. Supervisors were expected to have several skills, including being organized (with accurate note-taking commonly recommended), clear communicators and able to provide pastoral support and encouragement if required (e.g. Table 2 c). More specific suggestions about the conduct of supervision sessions included setting ground rules, providing timely and meaningful feedback and being available to students.

Supervision practice was often viewed as requiring a tailored approach which developed over time, based on student ability, with more directive feedback needed for less well-performing students and more high-level feedback required for students aiming for a distinction. It was acknowledged that this meant not treating students equally, but instead hopefully equitably (Table 2 d). There was general agreement amongst supervisors that flexible supervision was important and strict rules on contact hours per student (as occurs in some MPH degrees) seen as unhelpful. However, the system of varied contact time was deemed potentially problematic by some students (Table 2 e).

Supervisors’ reflections led to some advice for new supervisors. Amongst these was the need to remember that the project is the student's dissertation and not the supervisor's. It was also highlighted that supervisors would inevitably get better with experience but the budding supervisor should accept this as part of the process and forgive themselves for early mistakes.

Pressures on the dissertation process

A tension was identified between students developing their own research topic and the need for supervisors to have some knowledge of the dissertation topic. Some supervisors felt it was preferable for students to play an integral part in conceiving the research question (Table 3 b), while others felt this was unrealistic at the MPH level and within the dissertation timescale (Table 3 c). Other priorities, especially research, were often seen as competing with dissertation supervision but some supervisors attempted to align these two priorities—exemplified by aiming for academic papers resulting from dissertations (Table 3 d).

Tensions were identified between the dissertation as a credentialising tool and as a learning process. The former favours a standardized process which is amenable to clear marking guidelines. Within the department, attempts have been made to accommodate diversity in disciplinary approaches by having specific marking guidelines for different methodologies (such as systematic reviews and qualitative research). However, there was some criticism of this on at least two fronts (Table 3 e). First, the validity of such guidelines and their ability to allow comparison of different forms of research was questioned. Second, the focus on the end product as a piece of research was felt to potentially limit opportunities for conducting more practice-orientated work (as carried out within government departments or elsewhere), which might be more relevant to a student's learning requirements but less easily definable as a specific form of research (Table 3 f).

Main finding of this study

Students and supervisors generally agreed that the MPH dissertation serves several purposes, including providing an opportunity to develop skills, apply learning from taught courses and help prepare for future work. Supervision is often tailored to students’ evolving needs and while a number of behaviours facilitate basic competence, good supervision is to some extent learnt from experience. However, we identified tensions in the supervision process, with two ideal types discernible (see Fig. 1 ). Supervisor-led dissertations tend to be narrowly defined by the supervisor and well suited to the credentialising purpose of the dissertation. In contrast, a student-led dissertation is more tailored to public health practice and some students’ learning requirements. The latter may require greater supervisor effort and put the student at greater risk of failure when the end product is assessed against criteria for a research product. In reality, a broad continuum exists between these ideal types and they represent a negotiated process that unfolds over time, rather than equating to supervisors (who may tend to operate more in one mode than another but switch their practice depending on the project and student).

A representation of two ‘ideal types’ of the MPH dissertation process.

What is already known?

Existing pedagogical literature supports some of the themes we identify including what constitutes good supervision practice (such as subject expertise and guidance on time management and writing) and having a student focus. 22 , 23 A recent Dutch qualitative study of pedagogy identified the importance of Master's supervisors adapting to students’ needs, but not their expectations. 24 Similar diversity in Master's in Medical Education projects has been previously found, as have tensions between service commitments for NHS staff and their postgraduate supervision roles, prompting the authors to call for less reliance on service staff. 25

Views on the benefits of a research perspective for students appear mixed. Struthers et al . sought views from medical, veterinary and dental schools, finding that many academic staff felt research thinking and skills were important in informing professional practice. 26 In contrast, Gabbay highlighted a perceived gulf between public health research and practice some time ago, arguing for experiential learning grounded in the real world. 27 Much of the higher education research has focussed on whether research improves teaching quality but a meta-analysis found little relationship between the two. 28 In contrast, qualitative research suggested that a complex interplay exists between research and teaching which varies by each individual academic. 16

Achieving synergies across research and teaching is an academic priority in many institutions, with the publication of students’ research projects noted to be a potentially important way to encourage future researchers. 26 In addition, public health academic departments have long had close relationships with practice—a strength which could be diminished as a result. 29

What this study adds?

By identifying the diverse expectations and needs of students, we hope supervisors are better able to match their supervision style to deliver the best possible learning experience and that our model assists in achieving this. Our study also suggests that a linkage between research and teaching is not without risk since academics may focus on one over the other. 14 A research emphasis may result in public health practice skills being neglected. 3 Our study goes beyond viewing research and teaching as in opposition or synergy. Instead, it points to a potential parallel to the posited ‘squeeze on intellectual spaces’—occurring when researchers have their academic freedom limited by the increasing focus on producing applied knowledge. 30 Our findings raise the possibility that a comparable ‘squeeze on learning spaces’ may be occurring, where students’ freedom to explore and learn during the dissertation is curtailed—echoing a perceived decline in the intellectual environment experienced by postgraduate nursing students. 31 This may result in MPH graduates finding it more difficult to bring together disparate research approaches in the manner often required for practice.

Limitations of this study

This study investigated the topic of MPH dissertation supervision using qualitative interviews with supervisors and students, but several limitations exist. First, this is a small-scale study at a single institution. Further work is needed to establish the extent that these themes are evident elsewhere, including within more practice-oriented MPHs. That said, many respondents had experience of teaching elsewhere and supervisors felt dissertation supervision did not differ markedly between universities but more by supervisor. Second, while the interviewers’ institutional positions assisted in accessing interviewees, data obtained are influenced by our working relationships. For example, students may have been less open to voicing criticisms, particularly since the dissertation was ongoing. Lastly, while we have introduced a continuum of dissertation supervision types, this interpretation should be considered preliminary and further longitudinal studies to explore the evolving nature of supervision over time is needed.

We report several findings worthy of reflection by new and experienced MPH dissertation supervisors alike. An awareness of the different purposes may assist supervisors to tailor their own and their department's supervision. Tensions identified in supervision raise questions about how academic public health departments could best respond to students’ changing needs. We hope such critical reflection of current pedagogical practice will assist in improving training for future generations of public health professionals. 32

The authors would like to thank the study participants and the supervisor of their Postgraduate Certificate in Academic Practice qualification, Dr Catherine Bovill.

Supplementary data are available at the Journal of Public Health online .

This study received no specific funding; S.V.K. was funded by the Chief Scientist's Office of the Scottish Government (SCAF/15/02 and SPHSU15), Medical Research Council (MC_UU_12017/15) and NHS Research Scotland.

Berridge V , Gorsky M , Mold A . Public Health in History—Understanding Public Health . Maidenhead : Open University Press , 2011 .

Cohen J , Robertson AM . A postgraduate public-health course: from the students’ point of view . Lancet 1961 ; 277 : 102 – 5 .

Google Scholar

Griffiths S , Crown J , McEwen J . The role of the Faculty of Public Health (Medicine) in developing a multidisciplinary public health profession in the UK . Public Health 2007 ; 121 : 420 – 5 .

Evans D , Adams L . Through the glass ceiling--and back again: the experiences of two of the first non-medical directors of public health in England . Public Health 2007 ; 121 : 426 – 31 .

Pilkington P . Improving access to and provision of public health education and training in the UK . Public Health 2008 ; 122 : 1047 – 50 .

Jenner D , Hill A , Greenacre J et al. . Developing the public health intelligence workforce in the UK . Public Health 2010 ; 124 : 248 – 52 .

Katikireddi SV , Higgins M , Smith KE et al. . Health inequalities: the need to move beyond bad behaviours . JECH 2013 ; 67 : 715 – 6 .

McMichael AJ , Beaglehole R . The changing global context of public health . Lancet 2000 ; 356 : 495 – 9 .

McPherson K , Taylor S , Coyle E . For and against: public health does not need to be led by doctors . BMJ 2001 ; 322 : 1593 – 6 .

El Ansari W , Oskrochi R . What matters most? Predictors of student satisfaction in public health educational courses . Public Health 2006 ; 120 : 462 – 73 .

El Ansari W , Russell J , Spence W et al. . New skills for a new age: leading the introduction of public health concepts in healthcare curricula . Public Health 2003 ; 117 : 77 – 87 .

El Ansari W , Russell J , Wills J . Education for health: case studies of two multidisciplinary MPH/MSc public health programmes in the UK . Public Health 2003 ; 117 : 366 – 76 .

Le L , Bui Q , Nguyen H et al. . Alumni survey of Masters of Public Health (MPH) training at the Hanoi School of Public Health . Hum Resour Health 2007 ; 5 : 24 .

Fox MF . Research, teaching, and publication productivity: mutuality versus competition in academia . Sociol Educ 1992 ; 65 : 293 – 305 .

Gunn V , Draper S , McKendrick M . Research-Teaching Linkages: Enhancing Graduate Attributes—Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences . Mansfield : The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education , 2008 .

Google Preview

Robertson J , Bond CH . Experiences of the relation between teaching and research: what do academics value . High Educ Res Dev 2001 ; 20 : 5 – 19 .

Pilcher N . The UK postgraduate Masters dissertation: an ‘elusive chameleon’ . Teach High Educ 2011 ; 16 : 29 – 40 .

Delamont S , Atkinson P , Parry O . Supervising the PhD. A guide to success . Maidenhead: Open University Press, 1997 .

Kendall M , Murray SA , Carduff E et al. . Use of multiperspective qualitative interviews to understand patients’ and carers’ beliefs, experiences, and needs . BMJ 2009 : 339 .

Glaser BG , Strauss AL The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research . New Jersey : Transaction Books , 2009 .

Mason J. Qualitative Researching , 2nd edn. London : Sage Publications Ltd , 2002 .

McMichael P . Tales of the unexpected: supervisors’ and students’ perspectives on short‐term projects and dissertations . Educ Stud 1992 ; 18 : 299 – 310 .

Harrison R , Gemmell I , Reed K . Student satisfaction with a web-based dissertation course: findings from an international distance learning master's programme in public health . Int Rev Res Open Dist Learn 2014 ; 15 : 182 – 202 .

de Kleijn RAM , Bronkhorst LH , Meijer PC, et al. . Understanding the up, back, and forward-component in master's thesis supervision with adaptivity . Stud High Educ 2014 : 1 – 17 . http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.980399 .

Pugsley L , Brigley S , Allery L et al. . Making a difference: researching master's and doctoral research programmes in medical education . Med Educ 2008 ; 42 : 157 – 63 .

Struthers J , Laidlaw A , Aiton J , et al. . Research-Teaching Linkages: Enhancing Graduate Attributes—Medicine, Dentistry and Veterinary Medicine . Mansfield : The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education , 2008 .

Gabbay J . Courses of action—the case for experiential learning programmes in public health . Public Health 1991 ; 105 : 39 – 50 .

Hattie J , Marsh HW . The relationship between research and teaching: a meta-analysis . Rev Educ Res 1996 ; 66 : 507 – 42 .

Bhopal R . The context and role of the US school of public health: implications for the United Kingdom . J Public Health (Oxf) 1998 ; 20 : 144 – 8 .

Smith K . Research, policy and funding—academic treadmills and the squeeze on intellectual spaces . Br J Sociol 2010 ; 61 : 176 – 95 .

Drennan J , Clarke M . Coursework master's programmes: the student's experience of research and research supervision . Stud High Educ 2009 ; 34 : 483 – 500 .

Larrivee B . Transforming teaching practice: becoming the critically reflective teacher . Reflect Pract 2000 ; 1 : 293 – 307 .

- public health practice

- public health medicine

- professional supervision

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1741-3850

- Print ISSN 1741-3842

- Copyright © 2024 Faculty of Public Health

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

share this!

March 20, 2024

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies . Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

Motivated supervision increases motivation when writing a thesis, study finds

by Gunnar Bartsch, Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg

Students working on their Bachelor's or Master's thesis usually have supervisors at their side who guide, accompany and possibly also correct them during this time. If students have the impression that their supervisor is passionate and motivated, this also increases their own motivation. Grade pressure, on the other hand, has no direct influence on student motivation during this time.

These are the key findings of a study conducted by psychologists at Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg (JMU). Dr. Anand Krishna, research associate at the Chair of Psychology II: Emotion and Motivation, was responsible for the study. The team has now published the results of its research in the journal Psychology Learning & Teaching .

The pinnacle of learning

"We surveyed a total of 217 psychology students across Germany who were writing their final thesis or had written it in the previous two years," says Krishna, describing the approach. For many students, this thesis represents an important milestone; after all, it can be seen "as the culmination of learning and an expression of the skills acquired during their studies." Accordingly, it is important to keep motivation as high as possible during the work.

The theoretical basis of this study lies in so-called Expectancy-Value Theory. Put simply, it assumes that people multiply the attractiveness of the respective goal, i.e., the value, with the probability of achieving it in their work.

The result of this calculation then determines the respective motivation. Or, in concrete terms: a good grade in the thesis is a prerequisite for an attractive job—so the value is high. However, those who feel overwhelmed by their work will see their chances of a good grade decrease. Accordingly, motivation is also low.

"The close correlation between students' motivation and their assessment of their supervisor's motivation is not really surprising," says Anand Krishna. However, there have been no scientific studies on this to date. What he finds more interesting is the finding that the pressure of grades in the final thesis is not directly related to student motivation.

Grade pressure increases stress and motivation

"Viewed in isolation, our analysis shows a positive correlation between grade pressure and the value aspect of motivation. The greater the pressure that students feel, the higher their motivation ultimately is," says Krishna. At the same time, however, more pressure always means more stress, which in turn lowers motivation.

"Based on this data, we believe it is plausible that grade pressure boosts motivation through the value of the grade, but also increases student stress and therefore ultimately does not contribute to motivation," Krishna concludes. It is important for him to point out that the results of this survey only indicate correlations, not causal relationships. However, the patterns in the data would not contradict the theoretical causal explanation.

Given that motivated supervisors play an important role where the grade is of great importance for future prospects, Anand Krishna and his co-author Julia Grund therefore consider it important to motivate and incentivize supervisors especially. After all, such measures will most likely be reflected in the perception of their students and ultimately lead to a better grade.

Provided by Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Prestigious journals make it hard for scientists who don't speak English to get published, study finds

4 hours ago

Scientists develop ultra-thin semiconductor fibers that turn fabrics into wearable electronics

5 hours ago

Saturday Citations: An anemic galaxy and a black hole with no influence. Also: A really cute bug

6 hours ago

Research team proposes a novel type of acoustic crystal with smooth, continuous changes in elastic properties

7 hours ago